April 8, 2025 – Day 51 of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Jungto Buddhism Course Lecture 5, BDG Interview

Hello everyone. Today is the 51st day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk and the day of the 5th lecture for the Jungto Buddhism Course.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center for his Jungto Buddhism Course lecture. The courtyard of the center was beautifully decorated with colorful lanterns in preparation for Buddha’s Birthday, which was a month away.

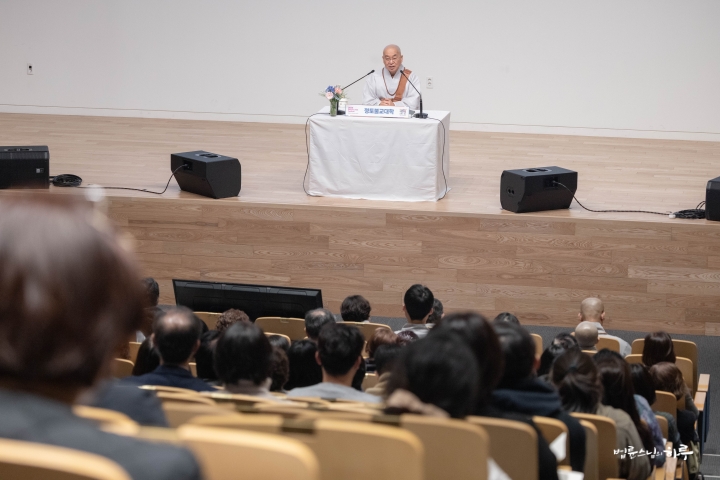

At 10:15 AM, the morning session of the Jungto Buddhism Course began. About 180 students were present in the main hall of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center, while approximately 170 more were connected to the online live broadcast. After reciting the Three Refuges and Words for Practice together, and requesting the Dharma teaching with three bows, Sunim began his lecture.

During the previous four lectures, students had learned about Buddhism’s core concepts: the Four Noble Truths, Dependent Origination, the Middle Way, and the Eightfold Path. Sunim briefly summarized these previous lectures before continuing with today’s topic: “What is the correct value system?”

“Before the ancient slave system emerged, humanity’s first social system was primitive communism. In primitive communism, the same ethics applied to everyone. As social systems gradually developed, value systems diversified according to different eras and regions. That’s why someone from the Joseon Dynasty would struggle to adapt if they time-traveled to today’s modern society, and likewise, modern people would find it difficult to adapt to the Joseon era. Even among contemporaries, ethical standards differ by region. People living in the same era but in different places—Korea, Japan, or Saudi Arabia—experience completely different applications of ethics. This raises the question: ‘What is the correct value system?’ If ethics apply differently depending on the situation, how can we establish a concept of justice?

The What is the Correct Value System?

Within specific religions, eras, regions, and cultures, what is right and wrong may seem clear, but when viewed comprehensively, these distinctions become ambiguous. Ultimately, there is no absolute standard that can be called justice.

All values are relative. However, specific groups such as religions or nations try to make their values absolute. When people absolutize their own value systems, they can reach a point where they believe it’s acceptable to kill those who think differently. This might sound like an extreme exaggeration, but it’s something we frequently see in our society today. South Koreans who hate North Korea think, ‘Those people deserve to die.’ Similarly, North Koreans think, ‘South Koreans deserve to die.’ Around the world, people are killing others with different value systems amid conflicts over religion, politics, and ethnicity. Thoughts like ‘Your thinking is wrong, so you must change it’ or ‘If you don’t change, you deserve to die’ arise because people absolutize their own value systems. Even in Korea recently, when the president declared martial law, there were reportedly orders to ’round them all up.’ This reflects the belief that those with different opinions can be imprisoned or even killed if necessary. When the president was impeached due to the illegal declaration of martial law, the situation reversed. Now people say, ‘We must crush all those who supported the rebellion.’ From the perspective of wanting to eliminate those with different opinions, both sides are essentially the same.

The Harmful Effects of Absolutizing Value Systems

Today, Korean society is caught in extreme polarization. The political forces on both sides have reached a level of mutual hatred. Even if not expressed verbally, underlying thoughts like “Those people should be locked up” or “Those people should be eliminated” exist beneath the surface. This is why they cannot sit at the same table for dialogue. Currently, to amend the constitution, ruling and opposition parties need to sit at the negotiation table together, but those who call themselves democratic forces argue that sitting at the same table with those who allegedly supported insurrection would be tantamount to condoning insurrection. As the situation turns in their favor, they become increasingly arrogant. After the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye, they labeled the opposing faction as “accumulated evils” that needed to be eradicated. By insisting on eliminating these “accumulated evils,” they ultimately strengthened the opposing forces. If they continue to corner the opposition now, those forces will unite again. Currently, the opposition is fragmented due to differences in positions on martial law and impeachment, but when pushed into a corner, they will gather strength. This would effectively revive them. As the Bible says, those who try to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life will save it.

I am not trying to criticize any particular political group. I’m using this example to illustrate the harmful consequences of absolutizing one’s values. This happens in everyone’s daily lives. It’s easy to think that children should be hit when they don’t listen. Some teachers ask, “How can education work if we can’t discipline students physically when they don’t obey?” In the military, some people raise the issue, “How can we train soldiers without harsh discipline?” These are also examples of absolutizing one’s values. In fact, we are all tyrants in some way. Perhaps that’s why we sympathize with tyrants—because we ourselves are tyrants too.

The Path to Resolving Conflict and Achieving Peace

To move toward peace, first, we must acknowledge that values are relative. We are simply different from one another. Christian values differ from Buddhist values, and Korea’s position differs from Japan’s position. The perspectives of the ruling class differ from those of the ruled, and the views of employers differ from those of workers. Everyone applies different value standards. If everyone shared the same standards, we wouldn’t be fighting so fiercely as we do now. Also, if people lived completely separate lives, things might be fine. However, when people live together in the same space as spouses or as parents and children, conflicts inevitably arise. If conflicts occur even among family members living in the same house, how much more so among the members of an entire nation?

In the past, Christians lived among Christians, and Buddhists lived among Buddhists. Koreans lived in Korea, and Japanese lived in Japan. But now, Thai people come to live in Korea, as do Japanese people. People from all over the world live together. The same applies to religion. Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims all live in the same country. The values of the older generation differ from those of the younger generation, and men’s perspectives differ from women’s. When all these people live together in the same space and time, conflicts are inevitable. Initially, we only had regional conflicts, with voting patterns divided between Jeolla and Gyeongsang provinces. Now, generational and gender conflicts have become even more problematic than regional ones. As society modernizes, conflicts intensify. Therefore, to move toward peace, we must first acknowledge that “we are different from one another” and “values are relative.”

Second, we need to understand that values are not inherent but formed. Values were not given by God or present from the beginning. Even if they have been passed down from ancient times, they were all formed at some point. I may not have created them myself, but someone created them and passed them down. If values existed from the beginning, they would be absolute. If they were formed, they can be changed. This doesn’t mean we should change everything unconditionally. The fact that values are formed means they are not absolute and can therefore evolve.

When conflicts arise while living together, we should first adopt the perspective that “we have different thoughts.” If you accept that “my spouse thinks that way” or “my children think that way,” you won’t get angry. It’s simply that we’re different from each other. For example, if people living in the same house have different preferences—one feels cold while another feels warm—how should this problem be resolved? There are several possible solutions. Since their physical constitutions differ, they could agree on a compromise temperature, or one side could yield completely. Compromise means choosing a middle ground, while yielding means supporting one side’s wishes. In modern society, the process of finding compromise and concession often defaults to majority rule, which always leaves the minority feeling wronged. So when agreement seems impossible, using separate rooms is another option. This too can be seen as a form of compromise, though it costs more money since you need an extra room.

This process of finding common ground while acknowledging our differences is “politics.” Democracy is about finding a balance of interests when they conflict and gathering consensus when opinions differ. In contrast, totalitarianism occurs when one person becomes absolute, imposing their decisions and silencing different opinions through violence. Democracy means creating points of agreement by coordinating everyone’s opinions. In this process, we should never say, “That opinion is nonsense.” Even opinions that seem less rational are still valid opinions. Through discussion, such views may become the minority. It’s through this process that opinions converge and decisions are reached.

Characteristics of Buddhist Values

What are the characteristics of Buddhist values? Of course, Buddhist values are also relative when compared to others. We cannot claim that all value systems are relative while only Buddhism is absolute. We must acknowledge that Buddhist values are also relative. However, Buddhist values, first and foremost, emphasize “universality.” They don’t apply differently to ruling classes versus the ruled, or to men versus women. Universality means seeing all people as one community and applying principles universally. Rather than fragmenting by class or gender and applying different standards, Buddhism applies the same principles to everyone. Buddhism has created values centered on commonalities while acknowledging the differences among various races and ethnicities. Therefore, Buddhist values possess a universality that even followers of other religions can accept. Nevertheless, we should be cautious about absolutizing Buddhist values.

Second, Buddhist values consider not only humans but also the natural ecosystem. Until now, all ethics and morality in human culture have only considered humans. Nature was not a consideration. However, as ecological destruction has become serious in modern times, the term “ecological ethics” has emerged. The argument that human ethics alone are insufficient and that human ethics should be based on ecological ethics is gaining persuasiveness. In this respect, although Buddhist values were established in the distant past, they can be considered the most suitable values for the current climate crisis era. Modern society needs new ethics. That’s why there are discussions about revising the Constitution of the Republic of Korea to reflect the climate crisis era. Buddhism has the advantage of having considered this point for a long time. Based on this foundation, let’s examine each of the Buddhist values known as the “Five Precepts” in more detail.“

Continuing, Sunim explained in detail the precepts of non-killing and non-stealing from the Five Precepts. Finally, after answering questions from students, he concluded the lecture.

As Sunim left the stage, the facilitator provided instructions for practice assignments. The students agreed to diligently work on their practice exercises until the following week and continued with mindful sharing in their groups.

After having lunch with the Sangha in the basement dining hall, Sunim had an interview at 1 PM with Buddhistdoor Global (BDG). BDG is an online Buddhist journal that provides various Buddhist content in English to Buddhists and practitioners worldwide. Sunim warmly greeted Craig, the reporter who came for the interview.

First, Craig asked about the purpose of the 100-Day Dharma Talk currently being held at the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

What is the reason for conducting the 100-Day Dharma Talk?

“First, Jungto Society has been operating online for five years now. While the online transition has many advantages, it also has shortcomings. The most significant deficiency is the loss of opportunities for people to meet in person and be personally inspired by one another. As a result, faith has weakened, and the motivation to take action has diminished. Naturally, when listening to Dharma talks at home, it’s easier to multitask, which reduces concentration. Therefore, we organized this offline ‘100-Day Dharma Talk’ event to strengthen faith and enhance practical implementation. In particular, this Jungto Social and Cultural Center was built to revitalize offline activities but couldn’t be properly utilized due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To activate this building, I needed to give Dharma talks in person. So, the main purpose is to revitalize our offline activities.

Second, Korean society is currently in a state of confusion. To help stabilize Korean society, I felt it necessary to stay in Korea for at least 100 days rather than traveling abroad. Besides the tensions between North and South Korea, there are severe conflicts among political factions within South Korea. To alleviate these conflicts, we need to pray sincerely and also engage in direct dialogue with social leaders to help them understand the opposing side. That’s why I postponed all overseas activities until after June and began the 100-Day Dharma Talk in February. Through these efforts, I hope to play even a small role in bringing peace to the Korean Peninsula.”

The interview continued with questions on various topics including international affairs, political conflicts in Korea, earthquake damage in Myanmar, and sustainable development in Bhutan.

Polarization is intensifying globally, increasing hostility toward opposing sides. What are your thoughts on this?

Korean politics still seems to have a well-functioning democracy with mutual checks and balances. How do you see the political conflicts in Korea evolving?

The international community has been unable to help the people of Myanmar due to military dictatorship. How might the recent earthquake in Myanmar affect JTS activities?

You are conducting sustainable development projects in Bhutan. What achievements have been made so far?

After an hour of interviewing, Craig asked his final question.

What global issues need urgent resolution now?

“Currently, rebuilding Syria is a major task. Although the Assad dictatorship has stepped down, most buildings in cities have collapsed due to 12 years of civil war, and the country has also suffered earthquake damage, making nationwide reconstruction a challenging task. There are no special sources of income domestically, and no international support. Half of the population has fled the country as refugees, and even if they want to return, their homes are destroyed, schools are gone, there’s no electricity, and hospitals are non-existent, making it impossible to sustain livelihoods. Like Koreans, Syrians highly value education, so their first request is to restore schools. We are currently in discussions with the Syrian government about rebuilding collapsed schools and hospitals.

First and foremost, the country I’m most concerned about is North Korea, as food shortages for its people remain unresolved. Second, Myanmar is facing food shortages and has also suffered earthquake damage, prompting JTS to dispatch an emergency rescue team. Third, Syria is experiencing significant difficulties in national reconstruction, and we are discussing how we might be able to help. North Korea, Myanmar, and Syria are the three countries currently in the most difficult situations.”

The interview concluded just after 3 PM.

Sunim spent the entire afternoon working in his office. Following President Yoon Suk-yeol’s impeachment, discussions about the need for constitutional reform have emerged, prompting social leaders concerned about the country to contact Sunim. Through numerous phone conversations, he continued to discuss how South Korea could move forward in the right direction.

As the sun set, Sunim began teaching the fifth session of the evening Jungto Dharma School class at 7:30 PM.

About 200 students who had rushed over after finishing work gathered in the basement auditorium, while approximately 340 others connected to the online live broadcast. They read the Three Refuges and Words for Practice together, then requested Sunim’s Dharma teaching with three bows.

Similar to his morning lecture, Sunim continued his explanation of the Five Precepts, the core values of Buddhism. Today, he provided detailed explanations of two of the Five Precepts: the precept against killing and the precept against stealing.

“What is the purpose of observing precepts? It is neither obedience to God nor faith in the Buddha. It is for our own liberation. What matters is whether something helps us progress toward a state free from suffering. To put it simply, anything that helps us reach the goal of liberation and nirvana falls under what we should do, while anything that doesn’t help falls under what we should not do. The goal of keeping precepts is liberation and nirvana.

Do Not Harm Living Beings

The first of the Five Precepts is to refrain from beating or killing living beings. This represents the value of respecting life. It doesn’t simply mean to respect life because it is life. Rather, respecting life is the first thing we must observe in our journey toward a state free from suffering. In one word, this is “non-violence.” Non-violence is the most important value in Buddhism. While striving for what you want is your personal freedom, you should never employ violent methods. In other words, you should not beat or kill others to achieve your goals. Whether you’re protesting, dating, making money, or doing anything else, you should never use violence to achieve your objectives. Teaching children properly is good, but hitting them to teach them is not acceptable. The scope of non-violence applies not only to humans but also to animals.

When reflecting on the precept against killing, you might think, “I didn’t hit anyone” or “I didn’t kill anything.” However, violence violates the precept whether you do it directly, have someone else do it, use tools to do it, enjoy it, or simply stand by and watch. This is the most important of Buddhism’s Five Precepts—the precept against killing (不殺生). You must not carelessly beat or kill living beings.

The precept against killing doesn’t just mean refraining from beating or killing; it also actively implies saving dying lives. In other words, it means “releasing life.” Even if someone is your enemy, if they are injured, you should save them. At the very least, civilians not directly involved in war should never be attacked. Of course, not waging war at all is best, but even in war, there are lines that should never be crossed. The indiscriminate attacks happening today in Gaza by Israel are not simply war but closer to massacre.

Do Not Harm Others

The second of the Five Precepts concerns the “value of protecting property.” In a narrow sense, it means not to take what is not given, and in a broader sense, it means not to harm others. What do people need to survive? We need to drink water and eat food. Without essentials like water and food, people cannot survive.

There is nothing as miserable as starving to death. When I lived in the countryside as a child, during the spring famine period, many people had yellowish faces from digging up and eating plant roots. Until the early 1960s, food shortage was a truly serious problem in our country. As the economy grew, we no longer had to worry much about starving to death. However, the famine situation in North Korea continues to this day. In the mid-1990s, when I was helping North Koreans at the border, I witnessed countless people who had died of starvation. Many people crossed the border to escape hunger, and I interviewed many of them. It was like experiencing a scene from history when massive numbers of people died during great famines, as if transcending time. The misery was beyond description.

So I went to the United States to explain the situation in North Korea and appeal for humanitarian aid. However, it was difficult to build empathy. In a prosperous, developed country like America, it was extremely challenging to effectively communicate that “people are starving to death right now.” From their perspective, it must have seemed strange to see an Asian monk visiting and crying while talking about North Korea’s situation. While South Koreans would typically object by saying, “Food aid to North Korea will come back as bullets,” Americans were even more detached. After hearing my entire story, they asked, “Do you have evidence that what you’re saying is true?” How could I produce evidence when I couldn’t even enter North Korea? So I went to China and interviewed about 270 North Koreans I met in the border region. I compiled statistics on how many people had starved to death and returned to the United States three months later. This time, they said, “That number of cases is not statistically significant.” So I invested another two months and created a report based on interviews with about 470 people. Only then did they begin to acknowledge the situation somewhat. Still, they said the numbers were too small, so I spent another year increasing the number of interviewees to 1,800. This is how difficult it was to help people who had never experienced starvation understand the issue of famine.

What I’ve just told you might pass through your ears without making an impact. It’s difficult to truly grasp how severe this suffering is without experiencing it firsthand. However, people who have experienced starvation express their pain in very concise ways. A North Korean resident I met said, “I traded my house for ten blocks of tofu.” Trading a house for ten blocks of tofu doesn’t make sense under normal circumstances, but that’s what happens in starvation conditions. Another person said, “If I could eat just ten eggs before dying, I would have no regrets.” When people are severely starving, something like this can become their final wish.

There’s an old riddle that asks, “What is the most terrifying sound in the world during a famine?” The answer is “the sound of scraping the bottom of a rice container.” When you scoop rice with a ladle and hear that scraping sound at the bottom, there’s nothing more frightening. Those who haven’t experienced this sound might laugh and ask, “What’s so scary about that?” In Buddhism, the being that symbolizes the suffering of hunger is called “hungry ghost” (gaki). The three painful realms one goes to after death for doing evil deeds are called the “three evil paths” (samakdo). The first is hell, and the second is the realm of hungry ghosts. This illustrates how severe the suffering of starvation truly is.

Why We Must Provide Humanitarian Aid Regardless of Country, Gender, Religion, or Ideology

Ultimately, this second precept concerns survival. Water and food are the most essential elements for survival. In the earthquake-affected areas of Myanmar right now, clean water and food are the most urgent needs. If it rains, tents will be immediately necessary, and if people are sick or injured, medicine is required. Water, food, clothing, shelter, and medicine—these five elements are absolutely essential for basic survival. Every human being has the right to have their survival guaranteed. We should never turn our backs on people saying, “Because you’re a communist,” “Because you’re a Muslim,” or “Because you’re a criminal.” The principle of humanitarian aid is that survival necessities should be provided unconditionally. Yet in our world, these essential survival items are stolen and taken away from people. This is essentially no different from pushing people toward death. That’s why the second precept instructs us not to take what is not given. It means that we should not forcibly take or steal the minimum resources necessary for another person’s survival. While this could be interpreted in capitalistic terms as “protection of private property,” the fundamental spirit is not to take or steal what relates to others’ survival. This is why we must provide humanitarian aid.

The key point here is not to violate the minimum resources needed for survival. While the expression ‘other people’s belongings’ is commonly used, the fundamental principle lies in protecting the right to survival. Therefore, practitioners should never say things like ‘North Koreans should starve to death.’ Whether it’s North Koreans, Muslims, or prisoners, if they have no water to drink or food to eat, we should provide for them, and if they are sick or injured, we should give them medicine. Yet we too easily say, ‘Bad people should be killed!’ Such statements are completely inconsistent with Buddhist values.

Today, I discussed two of the Five Precepts. First, we should not use violence. Second, we should not violate basic survival rights. These two values are universally valid principles that anyone can agree with, regardless of country, gender, religion, or ideology.”

The fifth lecture concluded with an agreement to learn more about the precepts of sexual misconduct and false speech in the next session.

Following this, the facilitator informed the students about their practice assignments, after which they gathered in groups for mindful sharing. Sunim then returned to the Seoul Jungto Center to wrap up his day.

Tomorrow will be the 52nd day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will conduct a live broadcast of the Weekly Dharma Assembly for the daytime session. In the afternoon, he will attend the new Dharma Teachers’ training to give a Dharma talk, and in the evening, he will conduct another live broadcast of the Weekly Dharma Assembly for the evening session.