April 7, 2025 – 50th Day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, 9th Sutra Lecture, 9th Buddhist Social Studies Course

Hello. This is the 50th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Now past the halfway point since the start of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today, there will be a sutra lecture and a Buddhist Social Studies Course.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to give the sutra lecture.

About 120 people were seated in the third-floor Dharma hall, while approximately 560 people connected via the online live broadcast. After the audience requested the Dharma talk with three full bows, Sunim ascended to the Dharma seat.

Today is the ninth session of the Diamond Sutra lecture series. Sunim first summarized the content from Chapters 1 through 16 that he had explained in the previous eight lectures, then began his explanation of Chapter 17.

“Chapter 17, ‘The Ultimate Non-Self,’ begins with Subhuti repeating the same question that appeared in Chapter 2, ‘Subhuti’s Request.’

‘World-Honored One! If good men and good women develop the mind of Anuttara Samyak Sambodhi (supreme enlightenment), how should they abide and how should they subdue their minds?’

This is the same question Subhuti asked in Chapter 2, but the context is different now. The Buddha answers as he did in Chapter 2, saying, ‘Develop the mind that seeks to liberate all sentient beings.’ Though the question and answer are the same, Subhuti’s intention is different. In Chapter 2, Subhuti was essentially asking, ‘How can I reach a state of peace?’ The Buddha, knowing Subhuti’s mind, answered, ‘If you truly wish to reach a peaceful state, develop the mind that seeks to liberate all sentient beings.’ In a way, Subhuti was trying to lighten his burden but ended up with more responsibility. It’s as if he asked, ‘How can I put down this heavy load on my shoulders?’ and the Buddha replied, ‘Develop the mind to carry others’ burdens as well.’ Moreover, the Buddha says that even if I were to carry everyone else’s burdens, in reality, not a single person would have their burden lightened. This is because if a bodhisattva has notions of self, person, sentient being, or life span, then he is not a bodhisattva.

Sentient Beings Are Not Actually Sentient Beings; They Are Just Called That

It sounds bewildering when the Buddha says that although one has developed the mind to liberate all sentient beings and has liberated many, in reality, not a single being has been liberated. To explain this principle, the Buddha uses numerous analogies—comparing it to giving, to seeing the Buddha’s 32 marks, to adorning Buddha lands—repeatedly explaining what it means to “not form attachments to appearances.” In other words, while in Chapter 2, Subhuti was asking as a practitioner of the Lesser Vehicle, through their dialogue, he has now come to understand what Mahayana Buddhist practice is about. In Chapter 17, he is asking as a Mahayana practitioner. The Buddha then answers:

‘If you think you are liberating sentient beings, you cannot be called a bodhisattva, because sentient beings are not actually sentient beings; they are just called that.’

By this point, one should understand the principle of not clinging to anything, but foolish people might think, ‘Since the Buddha says there are no sentient beings to begin with, then there’s no need to liberate them,’ and thus stray from the path again. They become lost once more. When told to abandon attachments to appearances, they form yet another attachment.

Similarly, when one becomes a practitioner, they initially leave the world to avoid being tainted by it, but over time, they come to enjoy dwelling in the forest and turn away from the world. That’s why the Buddha emphasized that those who have developed the Mahayana mind should cultivate compassion—the mind that feels empathy for sentient beings. The Buddha is perfect in both wisdom and compassion. While the Lesser Vehicle emphasized wisdom, the Mahayana emphasized compassion. This doesn’t mean that Mahayana Buddhism neglected wisdom. Rather, because the Lesser Vehicle paid less attention to compassion, Mahayana Buddhism emphasized compassionate mind. Therefore, the core teaching of Mahayana Buddhism is to develop a mind that gives, understands, and feels empathy—an active, engaged mind. This is collectively expressed as “developing the mind to liberate sentient beings.” The moment one transitions from the Lesser Vehicle mindset to the Mahayana mindset is precisely when one develops the mind to liberate sentient beings. To the Mahayana bodhisattva who has developed such a mind, the Buddha now says, “If you think you are liberating sentient beings, you cannot be called a bodhisattva.” This is the content of Chapter 17 of the Diamond Sutra.

This statement is similar to when Mahayana Buddhism criticized Hinayana practitioners for turning away from sentient beings and seeking their own comfort to avoid being contaminated by the world, saying “Save all sentient beings.” Even Mahayana Buddhist practitioners can easily become secularized if they lean too far in one direction. In fact, in Mahayana Buddhism, there have been instances where ordained monks got married or possessed wealth. The criticism directed at such individuals is: “If you think you are saving sentient beings, you cannot be called a bodhisattva.”

The Principle of Nothing Given and Nothing Gained

When Bodhidharma came to China, many people flocked to see this famous master from India. However, when they didn’t get what they wanted, they all turned away. After about nine years, when people stopped coming, only one person remained. When the master meditated, he meditated alongside him; when the master went for a walk, he walked with him, simply staying by his side without saying a word. One day, Bodhidharma called to him and asked, “Why are you here?” He replied, “I came to attain the way of peace of mind.” Bodhidharma then asked, “What is your mind like?” To answer this question, he had to look into his own mind. After examining his mind, he answered, “My mind is anxious.” Bodhidharma said, “Bring me that anxious mind, and I will pacify it for you.” This was a golden opportunity—if he could just present his anxious mind, it would be resolved.

But how does one find one’s anxious mind? Should one go to India? Should one search through scriptures? Rather than looking outward, one simply needs to be aware of one’s own mind. Through this dialogue, the master helped turn the disciple’s outward-seeking eyes inward to find the truth. There is no record of how much time passed as he searched for his anxious mind. The duration is not important; it only seems important because of our worldly perspective. Most accounts record it as if he answered immediately. Finally, he replied, “I cannot find anything to bring forth.” Realizing there was nothing that could be called “anxious” when examining his mind meant that his mind had already become peaceful. So the master said, “I have already pacified your mind.” This is the principle of nothing given and nothing gained.

This person was Huike, the Second Patriarch of Seon Buddhism who inherited Bodhidharma’s Dharma. This story well illustrates the spirit of Seon at its inception. If the Diamond Sutra best captures the early Mahayana Buddhist perspective, then the beginning of Seon is characterized by “direct pointing to the human mind.” It means attaining enlightenment by directly perceiving the mind, expressed as “directly pointing to the human mind, seeing one’s nature and becoming Buddha.” The Diamond Sutra states, “When you realize that all appearances are not appearances, you immediately see the Tathagata.” From the Seon perspective, among numerous sutras, the Diamond Sutra most closely aligns with Seon’s position. This is why, although Seon Buddhism does not rely on any particular scripture, it highly values the Diamond Sutra. It has become almost like the foundational text of the Seon school.

Korean Buddhism has inherited both Mahayana Buddhism and Seon Buddhism. This can be seen as having a rich Buddhist philosophy, or from another perspective, as somewhat complex. However, all these teachings share the same fundamental principles. The only differences lie in how they are expressed—whether as No Everlasting Abiding Dharma (無有定法), Emptiness (空), or Not Establishing Words and Letters (不立文字). With this in mind, I encourage you to examine the Diamond Sutra more deeply. The Diamond Sutra is not about news from within a dream but about awakening from the dream.”

Following this, Sunim led the group in chanting Chapter 17 of the Diamond Sutra from beginning to end, accompanied by the sound of the moktak wooden instrument, reflecting on its meaning before concluding the lecture.

The participants gathered in groups for mindful sharing, while Sunim moved to the dining hall on the first basement level to have lunch with the Sangha members.

In the afternoon, Sunim worked in his office and had phone conversations with senior social leaders about current national issues.

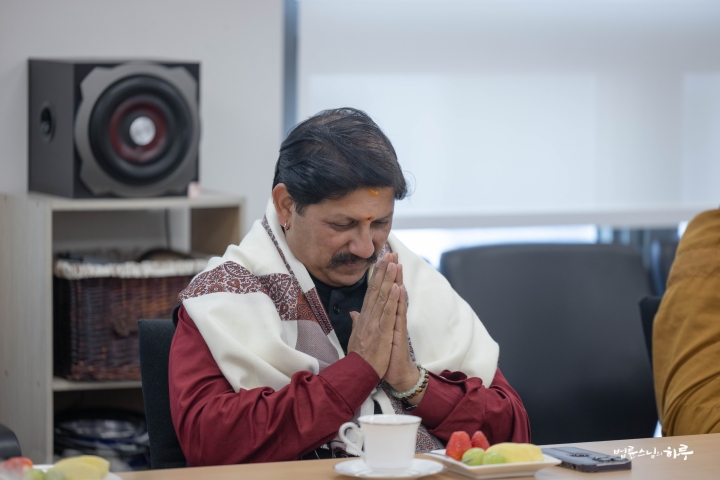

At 3 PM, visitors from India arrived. Dr. Ashish Bhave, Director of the International Institute of Culture in India, and his delegation visited The Peace Foundation through an introduction by Venerable Buddhapala, the abbot of Bunhwangsa Temple, a Korean temple in Bodhgaya, India.

After exchanging warm greetings, they shared news and updates. Dr. Ashish Bhave mentioned that he had been in Korea for a week, meeting with various experts to learn about Indian cultural influences and Buddhist culture in Korea. Sunim expressed his respect for the doctor’s research activities and discussed the exchanges between India and Korea.

“Last year, I attended the International Engaged Buddhism Conference in Chennai. The Buddhists in Chennai speak Tamil, and there are many similarities between Tamil and Korean languages. They claimed that Princess Ayuta, who introduced Buddhism to Gaya, departed not from Ayodhya in central India, but from Tamil Nadu.

Maritime Trade Routes That Existed Before Buddhism Was Introduced to Gaya

They explained that since ships in ancient times traveled with ocean currents, maritime trade between India and Gaya had already been established before the 1st century. The idea that someone would travel from Ayodhya along the Ganges River to the coast by boat seems impractical. Buddhism wasn’t suddenly transmitted to distant Gaya from the inland region of Ayodhya; rather, maritime trade routes already existed among merchants, and Indian monks followed these routes to reach Gaya. This means that even before Buddhism was introduced to Gaya, exchanges had been taking place for a long time between the Indian subcontinent and the Korean peninsula along these maritime trade routes.

While the prevailing theory in Korea has been that pottery, ironware, and other cultural artifacts were introduced from the north or west of the Korean peninsula, recent research reveals that iron civilization entered Gaya, a country established in the southern region of Korea, through sea routes from the south. Additionally, DNA studies of Korean people show that a significant number have genetic markers mixed with southern origins.”

Dr. Ashish also agreed with Sunim’s statement.

“That’s right. There have been exchanges among traders for a long time. I am certain that there were maritime exchanges not only with Korea but also with various countries in Southeast Asia. Recently, a seal from the Magadha Kingdom was discovered in Thailand.”

Sunim then emphasized that the Buddha’s teachings from 2,600 years ago already contained the spirit of democracy, equality, and women’s liberation that we pursue today.

“I have been giving lectures on Buddhist social thought here recently. One of the topics includes how the Buddha’s teachings and Indian traditions contained democratic values that preceded those of the West. Among the Buddha’s teachings, there are seven principles for preventing a nation’s downfall. One of them states, ‘Discuss freely but unite in consensus.’ However, when this was translated into Chinese, it was changed to say that the king and his subjects should maintain their proper roles and subjects should obey the king’s words. Also, the teaching to ‘not forcibly take women from other households’—essentially protecting the vulnerable—was changed during Chinese translation to emphasize that women should maintain their chastity. In Korea, we learned Buddhism as it was transmitted through China. As a result, we mistakenly believe that Confucian feudalism is the Buddha’s teaching.

The Buddha also spoke about six ways to achieve harmony. The first is to observe the same precepts together, which means equality before the law. The second is to align opinions with each other, which represents today’s democracy. The third is to distribute received donations equally, which signifies economic equality. In other words, the principles of rule of law, democracy, equality, and respect for human rights that we pursue today are all contained within our traditional philosophy.

How to Express Autonomy and Creativity

If we believe that everything has been imported from the West, we develop an inferiority complex about Western culture. I’m not suggesting we reject Western thought, but rather that we should rediscover valuable elements within our own traditions. We need to develop these further and work toward solving problems that the West has been unable to resolve. While we’ve caught up considerably in science and technology, our educational system still perpetuates the notion that the West is culturally superior. We must overcome this cultural inferiority complex to regain our autonomy, which is the foundation for creativity.”

“That’s right. Western scientific civilization and Eastern spiritual civilization need to harmonize with each other.”

Dr. Ashish then asked Sunim about the current state of inter-Korean relations and the risk of war on the Korean Peninsula. They agreed to continue their deeper conversation at their next meeting, and Sunim presented Dr. Ashish with ginseng as a parting gift.

After taking a commemorative photo together, Sunim bid farewell to Dr. Ashish and Venerable Buddhapala’s group.

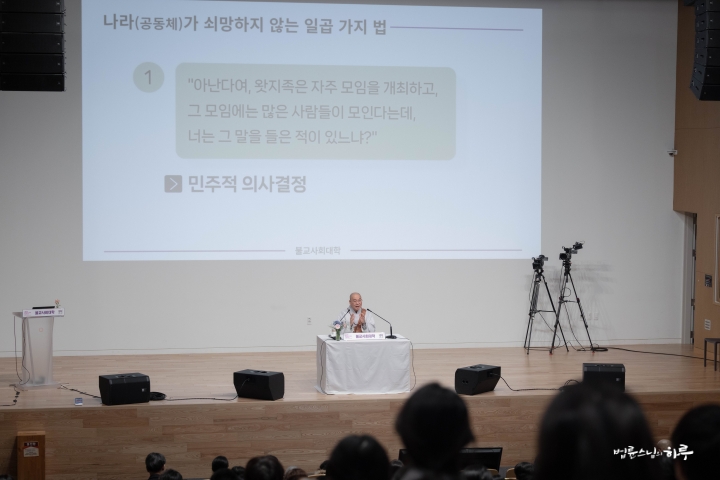

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim delivered the ninth lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course in the main hall of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. In the previous session, the class had learned about “What is justice from a Buddhist perspective.” After addressing several questions that had arisen from the last class, Sunim began today’s lecture on “Buddhism and Democracy.”

Comparing the Buddha’s Teachings with Modern Democracy

“Today’s lecture topic is ‘Buddhism and Democracy.’ We’ll examine how many democratic elements exist within Buddhism. The goal isn’t to interpret Buddhism through the lens of democracy, but rather to compare the Buddha’s teachings from 2,600 years ago with modern democracy.

This story takes place one year before the Buddha’s parinirvana, while he was staying at Vulture Peak in the kingdom of Magadha. At that time, King Ajatasattu of Magadha had killed his father to ascend to the throne. Initially, Ajatasattu was in conflict with the Buddha because his father, King Bimbisara, had been a patron of the Buddha. However, he soon repented and took refuge in the Buddha. At that time, King Ajatasattu was preparing to invade the Vajji confederation in Vaishali. One day, he sent a minister to ask the Buddha how he could win the war. While this might be framed as seeking advice, asking the Buddha how to win a war was inappropriate. Instead of answering directly, the Buddha called Ananda and asked him about the Vajji people.

If They Maintain These Seven Principles, They Will Prosper and Not Decline

The Buddha asked seven questions about the Vajji confederation. First, he asked whether they held frequent assemblies with high attendance. This suggests that for a country to be stable and prosperous, many people must gather frequently for meetings. This resembles the decision-making process in modern democracy. In contrast, the absolute monarchies of that time operated by royal decree—the king made decisions and subjects followed orders. So the Buddha was asking how the Vajji people governed their land. Ananda replied that the Vajji held frequent assemblies with high attendance. The Buddha then declared that as long as they maintained this practice, the Vajji would continue to prosper and not decline.

Second, the Buddha asked whether they met in harmony, adjourned in harmony, and conducted their affairs in harmony. Today’s democracy has the advantage of making decisions through discussion, but during the process, feelings can be hurt, and disagreements can lead to division. This point actually highlights a problem in current democratic systems. It suggests that while discussion should be free, once a conclusion is reached, everyone should unite behind it. Otherwise, democracy may be less efficient than totalitarianism. As global competition intensifies, efficiency becomes increasingly important. This has led some countries to devolve into one-person or one-party dictatorships. Notable examples include North Korea, Russia, China, India, and Turkey. Recently, Korea also faced a push toward dictatorship but was restrained by its citizens. In these countries, strong supporters meet strong leaders, preventing democracy from functioning properly. Even in Europe, we see far-right leaders taking power or far-right parties becoming dominant. In competitive situations, democratic decision-making may seem inefficient. However, if everyone unites behind decisions made after thorough discussion, this actually becomes the most efficient approach.

Third, the Buddha asked whether they refrained from arbitrarily changing established laws and were careful when establishing new ones. Just as we don’t trust people who constantly change their words, laws that frequently change don’t inspire compliance. Therefore, established laws shouldn’t be changed arbitrarily, and new laws shouldn’t be created carelessly. For example, general decisions typically require a simple majority, but creating or abolishing laws might require a two-thirds majority to prevent arbitrary changes. As the saying goes, laws shouldn’t change “morning to evening” but should maintain consistency and trustworthiness. However, having a constitution that remains unchanged for 40 years, like in our country, also has drawbacks. Treating laws as absolutely inviolable leads to rigidity, while frequent changes create disorder. We need to maintain fundamental principles while responding flexibly to social changes. This aligns with today’s concept of the rule of law. For the rule of law to function, laws must be trustworthy. This means that once established, they shouldn’t be easily broken, and new laws shouldn’t be created hastily.

Fourth, the Buddha asked whether they respect, honor, and listen to the elderly. This means young people should not disregard the elderly but should listen to and respect the opinions of experienced elders. Conversely, it’s also problematic when people in their eighties or nineties hold onto power. In any case, this implies that society as a whole should respect experienced elders and listen to their opinions.

Fifth, the Buddha asked whether they were kidnapping or detaining women from respectable families or unmarried women. At that time, women were treated almost like slaves, not as independent individuals. It was said that a woman had three masters in her lifetime (三從之道): her father when young, her husband after marriage, and her son after her husband’s death. If there were no men in the household, she wasn’t liberated but could be taken by anyone, like ownerless livestock. Thus, kidnapping or detaining women was common then. In modern terms, women would be considered socially vulnerable. The Buddha was asking how well the social safety net was constructed to protect such vulnerable members of society. In contemporary society, this would relate to how well basic rights are guaranteed.

Sixth, the Buddha asked whether they had preserved the ceremonies honoring and offering tributes to historically important sacred sites without abolishing them. In Korea’s Silla Dynasty, there were reportedly seven sacred sites. This question concerns whether they cherish their traditions and history. Our society has weak forces preserving traditional culture and still lacks historical consciousness. Whether it’s Japanese, Chinese, or American culture, there’s an attitude of “as long as I live well, nothing else matters.” This stems from a lack of self-identity. The Buddha was asking whether the Vajji people considered their self-identity important.

Seventh, the Buddha asked whether they treat those worthy of respect properly, listen to their stories, and make efforts to invite them to visit and stay in their country. In modern terms, this means inviting world-renowned scholars to hear their insights and listening attentively to their visions for future society. It signifies the need to contemplate the direction in which future society should progress.

Ananda told the Buddha, “I have heard that the Vajjians are practicing these seven principles.” King Ajatasattu had asked the Buddha about this because he was confident that he could conquer the Vajjians in one stroke, considering them insignificant compared to his kingdom of Magadha. In response, the Buddha did not say anything directly but instead asked questions to Ananda. This is characteristic of the Buddha’s dialogue style. As the king’s minister listened to the conversation between the Buddha and Ananda, he realized something important. He thought that if the Vajjians were observing even one of the seven principles the Buddha mentioned, it would be difficult to defeat them in war, let alone if they were following all seven. The minister replied, “I will return and discuss alternative approaches with the king,” and went back to Rajagriha.

In this way, the Buddha prevented a potentially major war before it could begin. He provided a framework for resolving the issue peacefully. The “Seven Principles for Preventing a Nation’s Decline” that the Buddha taught can certainly serve as valuable guidelines for managing our society today.

Six Criteria for Examining What’s Wrong When Conflicts Arise

Another story is about the “Quarrel of the Kosambi Monks.” Kosambi was one of the sixteen kingdoms at that time, where several hundred monks lived together. A conflict arose over a violation of bathroom usage rules. The dispute between two individuals escalated into a conflict between two groups of followers. The Buddha asked, “Why are you doing this? Listen to me,” as he spoke to one group and then went to speak to the other.

“Arguing about who is more right divides the Sangha. You are foolish people who, in trying to settle minor disputes, have committed a great sin.”

However, they replied, “Buddha, we will resolve this among ourselves,” and did not listen to the Buddha’s words. So the Buddha left that place. Later, when the lay community learned of this, they became angry. “How can practitioners not listen to the Buddha! What kind of people are these!” They refused to offer alms to the monks who came for food. Only then did the monks reflect on their actions, inquire about the Buddha’s whereabouts, and seek him out at Jetavana Monastery.

This is how the Buddha gathered the Sangha and spoke to them. First, he emphasized that the Sangha community must be pure. Purity means living frugally and observing the precepts well. Second, he emphasized that the Sangha community must be harmonious. Just as honey and milk become one, the community must be in harmony. When we examine why harmony breaks down, it’s because something has gone wrong among the six elements of harmony. However, when conflicts arise, we often try to resolve them forcefully by saying, “Be quiet! Be harmonious! Don’t fight!” If we just demand silence while ignoring underlying issues of inequality and injustice, the structural contradictions will never disappear. The absence of war doesn’t necessarily mean peace. If structural contradictions aren’t resolved, it may appear peaceful on the surface, but in reality, someone is suffering. That’s why the Buddha instructed us to examine the six elements of harmony. This is called the “Six Harmonies.”

First, everyone must observe the same precepts together. It’s unfair when some people follow the precepts while living together and others don’t. For instance, if some practice vegetarianism while others eat meat, or if someone tells others to dress modestly while wearing silk clothes themselves, that creates problems. When precepts are applied differently, dissatisfaction arises. Just as the saying goes, “All are equal before the law,” the application of precepts must be equal. In modern society, there’s a saying: “The rich are innocent, the poor are guilty.” This means that laws aren’t being applied equally. Thus, stealing ten dollars makes you a thief, but stealing a hundred million dollars becomes an economic activity. Killing one person makes you a murderer, but killing ten thousand might make you a hero. Everyone should be equal before the law. If the number of dissatisfied people in our society is increasing today, it’s because laws aren’t being applied equally. When the rules change depending on the situation or the person, of course people are going to get upset.

Second, opinions must be aligned frequently. This means when opinions differ, decisions should be made through democratic consensus. Whether through morning assembly or public hearings, when decisions are made through discussion, there are no complaints afterward. However, if one person makes all the decisions or simply gives orders, people may outwardly comply but inwardly harbor dissatisfaction. Naturally, they won’t follow when out of sight. Therefore, opinions must be aligned frequently. True democracy is unifying through right views.

Third, donated items must be distributed equally. This means achieving economic equality. Dissatisfaction arises if one person wears only good clothes while others are given shabby ones, or if one person has a large room while others sleep on the floor. That’s why economic equality is important. In our society today, the widening gap between rich and poor has created significant social instability. To prevent this, all donations, regardless of who they’re intended for, should be pooled and distributed fairly.

Fourth, we must live together in the same place. While the first three principles can be directly applied to our society, this fourth one is more challenging to implement as is. To adapt it for our society, we can interpret it as living transparently. When what I eat and do throughout the day from morning onward is transparent, mutual trust develops. Rumors spread precisely because people don’t know what others are doing. If we lived together in a room without partitions, transparency would be inevitable. During Buddha’s time, monks lived together in forest spaces without partitions. Every movement was clearly visible, making their lives transparent. This is why there was no conflict. When living transparently, the concept of privacy disappears. Yet modern people find this most difficult. Even practitioners who join the Jungto Society lay Sangha request, “It’s okay not to pay me, but please give me my own room,” or “It can be small, just give me a separate room.” This shows how difficult it is to live openly and transparently. Once partitions are removed, there’s actually nothing to hide, but psychologically, people want some barriers. Therefore, this principle means to disclose everything and live a transparent life.

Fifth, we must speak with compassion. When people living together use harsh words, conflict arises. In today’s society, speech has become a major issue. At protest sites or in internet comments, people use harsh language. Tongues become swords that kill with words. When even a member of the National Assembly says, “Let’s destroy the Constitutional Court!” it shows how bad things have become. While the anger behind such statements is understandable, public figures have responsibilities regarding what they say and how they behave. All of this is breaking down now. That’s why we must speak with compassion. There’s an old saying that “a kind word can pay off a huge debt”, but there’s also truth in the idea that “a single careless word can undo all the good you’ve done”. Thus, words can either bring blessings or become daggers. To achieve harmony, we must speak compassionately.

Sixth, we must respect others’ intentions. Here, “respecting intentions” means acknowledging and understanding opinions different from our own. People have different thoughts. Therefore, when conversing or discussing, we need to adopt an attitude that acknowledges different perspectives. However, when we get angry, we often dismiss others with comments like, “You call that speaking?” or “You call that thinking?” This isn’t about agreeing that the person is right, but acknowledging that they might think differently. That is what it means to respect others’ intentions.

When these six principles are observed, there is no conflict in the community. Instead of simply telling people to be quiet when conflicts arise, if we examine what the complaints are, we can discover which of these six principles have been violated. Perhaps in our society, none of these six principles are being observed. If we maintain this perspective and examine our situations accordingly, we can achieve harmony.”

Sunim then explained in detail the Karma (羯磨) system, a method by which the Sangha community resolves differences of opinion and conflicts through deliberation. He concluded the lecture after explaining the decision-making process of the Sangha, which is based on the principle of unanimous consent, and the meaning of Single Proclamation Karma (單白羯磨), One-Motion Karma (白二羯磨), and Two-Motion Karma (白四羯磨). Today’s session provided an opportunity to compare the Buddha’s teachings with modern democracy.

After the Dharma talk, participants gathered in groups for mindful sharing. Sunim returned to the Jungto Center and concluded his daily schedule.

Tomorrow will be the 51st day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will teach the 9th class of the daytime Jungto Buddhism Course, followed by an interview with a reporter from Buddhistdoor Global in the afternoon, and in the evening, he will teach the 9th class of the evening Jungto Buddhism Course.