Mar 17, 2025 – Day 29 of the 100-Day Dharma Talk , Sutra Lecture 3, Buddhist Social Studies Course Lecture 3

Hello. Today is the 29th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today features both a sutra lecture and a Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture. Spring is gradually spreading around the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. Fresh green buds are sprouting on branches that were bare all winter, and flower buds are beginning to bloom one by one. The warm breeze carries the news of spring, awakening the whole world.

After completing the morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center for the 100-Day Dharma Talk. The 9 a.m. morning service was held in the third-floor Dharma hall. After a brief preparation, at 10:15 a.m., the sutra lecture began with the Three Refuges and the recitation of the Heart Sutra.

About 120 people attended in person at the third-floor Dharma hall, while approximately 550 participated in the online live session, and 17 joined from the Haeundae Dharma Center, totaling around 680 participants. As the audience bowed three times to request a Dharma talk, Sunim ascended the Dharma seat.

Today is the third session of the sutra lecture series. Sunim began by summarizing the third section of the Diamond Sutra from the previous lecture, then explained the meaning of each passage using specific examples from daily life to make it easier to understand.

Chapter Three: The Right Doctrine of the Great Vehicle

“Continuing from our last session, let’s see Chapter Three of the Diamond Sutra in more detail. Subhuti asked the Buddha:

‘World-Honored One! How should good men and women who have awakened the mind of Anuttara Samyak Sambodhi abide their minds, and how should they subdue their minds?’

The Buddha told Subhuti three things. First, lead all sentient beings to complete nirvana. Second, after liberating all beings, in reality, no being has been liberated. Third, if one retains the notion of a self, a person, a sentient being, or a life span, then that person is not a bodhisattva. What do these three points mean?

To help you understand, let me share an example from a Dharma Q&A session. A questioner who was struggling with her husband’s drinking problem asked me:

Husband’s Daily Drinking Is Making My Life Miserable

‘I’m suffering terribly because of my husband. He loves alcohol so much that he drinks every single day of the year and always comes home late. Sometimes he doesn’t come home at all. When he does come home, he becomes belligerent and makes life unbearable. Someone told me that praying at a temple would help, so I made offerings, but there was no change in my husband. My friend said that church is more spiritually powerful than the temple, so I also went to church and prayed. I even had a shaman ritual performed after hearing that my husband was possessed by an alcohol spirit, but nothing worked. What should I do?’

I told her to prepare a drinking table for her husband every day when he returns from work. I suggested she sit beside him and pour him drinks. If that was too difficult, I advised her to bow 300 times daily while praying, ‘Buddha, alcohol is medicine for my husband.’ It doesn’t matter what effect alcohol has on others. For her husband at least, alcohol is medicine. And medicine should be taken every day without fail. She should prepare a drinking table every evening, and on days when her husband drinks outside and comes home, she should make hangover soup for him. It’s a good thing that he’s taking his medicine on his own. She should praise him when he remembers to take his medicine and help him when he forgets. When I first explained this, the questioner didn’t understand my meaning, but after further explanation, she nodded and said, ‘Yes, I understand,’ before leaving.

When I have these conversations with ten people, how many of them do you think actually follow my advice? Maybe two or three at most. People ask me what they should do because they’re struggling, but they don’t really listen to my answer. After the Dharma Q&A, some even leave the hall complaining that Sunim is asking them to do strange things. Usually, they try once or twice and quickly give up, thinking, “Why should I prepare a drink tray for someone like that?” But those who overcome these challenges and diligently follow my instructions come back to see me after about 100 days. That’s when the effects become clearly visible. They return happily, saying that following my instructions has produced miraculous results.

“Sunim, my husband comes home early these days, drinks less, and seems like a different person. So now I’m doing 500 prostrations instead of 300 in my daily practice. Of course, I’m also preparing nice drink trays for him.”

After hearing this, I said:

“You’re not praying properly.”

Hearing this, the questioner pouted and said:

“That’s not true. I pray very diligently. I used to do 300 prostrations, but now I do 500.”

She had come to express gratitude but became upset when told she wasn’t praying properly. Then, about 100 days later, she visited again.

“Sunim, all the spiritual power and miracles are gone. This man is drinking every day and coming home late again. I feel like praying is pointless. I want to stop.”

“What did I tell you last time? I said you weren’t praying properly, didn’t I?”

“Sunim, I prayed diligently.”

“You were just doing prostrations, not praying.”

This conversation contains the teaching from the third section of the Diamond Sutra. We pray for what we want. The questioner was praying for her husband to change according to her wishes. This is the typical purpose of prayer for Buddhist followers, their method of seeking blessings, and their approach to pursuing happiness. When things go their way, they say their prayers were effective; when they don’t, they say their prayers were ineffective. She came to me after failing to change her husband through her own efforts and seeking help elsewhere. I suggested she try the opposite approach. Since her husband was someone who would deliberately do what he was told not to do, I advised her to think differently—specifically, to stop telling him not to do things. She had believed her approach was correct, but when she followed my advice, it worked immediately. She didn’t understand why, but her husband changed somewhat, and she felt good about this seemingly miraculous change. She came to express her gratitude, but I told her she hadn’t been praying properly.

Why did Sunim respond that way? Because the questioner was praying from a place of ordinary mind. Ordinary people want situations to unfold according to their desires. When things go as wanted, they feel happy; when they don’t, they suffer. However, there’s no guarantee that getting what we want will bring only happiness. Many people have ruined their lives by achieving exactly what they desired. And since we cannot fulfill all our desires, suffering inevitably follows. This is how pleasure and suffering continue in a cycle. Yet we still cling to these desires.

Asking “How can I live without suffering?” is essentially asking to be saved. To such people, the Buddha suggested changing perspective: “Live by helping others rather than seeking help,” and “Live by understanding others rather than seeking to be understood.” To those asking for personal salvation, he paradoxically advised, “First, develop the mind that wants to help others.”

Similarly, when a woman came seeking help to stop her husband from drinking, Sunim suggested she change her thinking to “Alcohol is medicine for my husband.” Does a husband stop drinking just because his wife tells him to? Conversely, would he drink more than usual if she encouraged him to drink? The issue here is that the questioner keeps thinking, “If I tell him not to drink, he won’t drink; if I tell him to drink, he’ll drink more.” People generally live according to their own ways rather than following others’ instructions. Whether a wife tells her husband to drink or not to drink, he will drink as much as he wants. He might temporarily seem to listen to his wife, but over time, he’ll return to his usual habits.

When I tell my husband not to drink and he doesn’t, I feel good; when he drinks despite my request, I feel bad. But what if I try the opposite approach? If I tell him to drink and he does, I feel good because he’s listening to me; if he doesn’t drink, I feel good because he’s not drinking. The solution doesn’t require the other person to meet my demands. Sometimes changing my own perspective can resolve the issue. Conflict arises when you tell a drinker not to drink, but if you tell them to drink instead, the problem disappears. (Laughter)

So there’s no need to bow to the Buddha. Just changing one thought solves all problems. Because you couldn’t change that one thought, I gave you the prayer that “alcohol is medicine.” How can alcohol be medicine when it’s actually poison? That’s why there’s a condition at the beginning: “For my husband, alcohol is medicine.” That’s the prayer I gave you. Why is alcohol medicine for your husband? Your husband has something that makes him feel suffocated. If he keeps suppressing that feeling, he’ll suffocate to death. He drinks because he wants to live. Talking to you about his troubles only leads to arguments, so he drinks to breathe and survive day by day. Objectively, alcohol is poison, but I’m not saying you should think of it as medicine. I mean that for your husband, alcohol is truly functioning as medicine. Recognizing medicine as medicine is understanding the truth.

Since alcohol is medicine for your husband, he should drink it, right? Previously, you would have fought with him for coming home drunk, but now you can be grateful that he’s taking his medicine. “Welcome home. Was today difficult too? I see you had a drink.” And on days when he comes home without drinking, prepare a drink for him at home. Then there will be no conflict whether he drinks or not. Whether your husband drinks or not, once you change your thinking, your problem is already solved. What changes after your problem is solved? From your husband’s perspective, the biggest stress among his many stresses comes from you. But when that stress disappears, your husband’s overall stress decreases. With less stress, he drinks less. As time passes, he’ll think it’s better to drink at home than outside. Before, he would wander outside because you nagged him, but now that you serve him drinks, don’t nag, and even praise him, there’s no reason to spend money drinking outside. So from your perspective, your husband has changed. “Has the prayer finally worked? Sunim’s advice really worked!” That’s why you came to thank me, saying a miracle happened and your husband changed.

But you haven’t prayed properly. Being happy that your husband has changed is not practice. Initially, you were suffering because your husband drank. Now you’re happy because he doesn’t drink. This is just the cycle of suffering and pleasure. The cycle of suffering and happiness belongs to the realm of sentient beings. You mentioned doing 300 bows and then feeling so good that you did 500, but that’s just leg exercise, not practice. When you don’t practice properly, suffering inevitably follows.

Why did the questioner do 500 bows? She probably felt good because her husband was drinking less. So she wanted her husband to change more quickly and more significantly. With that mindset, she increased her bows, but her husband didn’t change as much as she wanted. When she had assumed he wouldn’t change at all, even a small improvement made her extremely happy. But once she saw a little change, she became greedy and started doing 500 bows daily, only to feel stressed again when her husband didn’t change further. Because of her suffering, she started nagging her husband again: “You were drinking less for a while, but now you’re drinking again.” This is how she returned to where she started. This is precisely how suffering and happiness continue in a cycle of samsara.

First, Don’t Seek Help, But Cultivate a Mind That Wants to Help Others

The key here is to cultivate the opposite mindset in order to win over someone’s heart. In the “Practitioner’s Attitude,” which is part of Jungto Society’s 1000-Day Practice, there is this expression:

“I will live with love, not hatred. I will live with understanding, not seeking to be understood. I will live by helping others, not seeking help…”

The first step in winning someone’s heart is changing your own mind like this. However, simply changing your mind doesn’t resolve all suffering. That’s why the second step is to eliminate expectations. When I help someone, the thought “I helped that person” arises. What happens when I think my prayers changed my husband, or my help saved someone’s life? If the person I helped doesn’t thank me, I feel bad. When I say I’m helping you, I inevitably expect my efforts to be acknowledged.

Second, Do Not Expect Anything in Return After Helping Others

If you have a mind that seeks to gain, you are an ignorant being, but if you have a mind that gives, you are a wise being. However, merely changing your mind to give only frees you from about half of your suffering. Ordinary beings expect things from others even without having given anything, so naturally, if you have given something, you will expect something in return. That’s why the second stage is to have no expectations after helping others. When you have no expectations, there is no trace of your act of giving. Having no trace means that no suffering arises, leaving no residue. It’s like a bird flying through the sky without leaving any trace behind.

This is why the third section of the Diamond Sutra continues with “deliver all beings, yet in reality no being is delivered.” When we adopt this perspective, we can completely free ourselves from suffering. This is the way to completely surrender the mind. We must not remain at the first stage of changing our minds but move on to the second stage of having no expectations. However, most people cannot even get past the first stage. Even if they do pass the first stage and become Buddhist followers or renounce the world to join a community, most cannot pass the second stage. In other words, the root of being an ordinary being has not been pulled out.

This is easy to understand if we pay a little attention to our daily lives. It’s not reasonable to expect to receive without giving. How could the world function if everyone only wanted to receive and no one was willing to give? A wise person thinks, ‘Giving is the best way to receive.’ There’s a proverb that says, ‘Kind words will bring kind responses.’ However, upon closer examination, even this approach is merely developing a giving mindset in order to receive more. The difference between these two attitudes is that one intends to receive without giving, while the other calculates to receive at least as much as one gives. One wants to receive without giving, and the other wants to receive after giving. While there’s a world of difference in terms of giving, both share the same desire to receive. The fundamental thought of needing to receive remains unchanged. Of course, when I give, the probability of receiving compensation increases. But proportionally, resentment also grows. Why? Because not only do I consider it natural to receive as much as I give, but I also develop a desire to receive with interest.

Third, If You Distinguish Between You and Me, You Cannot Completely Escape Suffering

The root of this mindset is precisely the four attachments: attachment to self (asang), attachment to persons (insang), attachment to sentient beings (jungsaengsang), and attachment to life span (sujasang). When translated from Sanskrit, their meanings vary slightly, but if we interpret them according to their Chinese translations, they become relatively easy to understand. First, attachment to self (asang) is the thought that distinguishes between oneself and the world, thinking “this is me.” Second, attachment to persons (insang) is the thought that distinguishes between humans and non-humans. Instead of considering humans as one type of animal, we think of them as completely different beings. In a broader sense, it’s distinguishing between humans and non-humans, and in the narrowest sense, it’s distinguishing between family and non-family. The term “our family” distinguishes between our family and others’ families, and “our country” distinguishes between our country and other countries. This way of distinguishing people, expanding from “our family” to “our humanity,” is attachment to persons. Third, attachment to sentient beings (jungsaengsang) is the thought that distinguishes between sentient beings and non-sentient beings. Sentient beings include not only humans but also animals and celestial beings. Therefore, the concept of “sentient being” can also be seen as a kind of boundary. Fourth is attachment to life span (sujasang). Literally interpreted, it refers to living beings. All living entities, whether plants or bacteria, have a lifespan and experience birth, aging, sickness, and death. Setting a boundary around life and distinguishing between living and non-living things is attachment to life span. More broadly, it can also be seen as distinguishing between existence and non-existence, or “being” and “non-being.” To explain simply: distinguishing between myself and what is not me is attachment to self; distinguishing between humans and non-humans is attachment to persons; distinguishing between sentient beings and non-sentient beings is attachment to sentient beings; and distinguishing between living and non-living things is attachment to life span.

If you have a mind that makes such distinctions, you cannot reach a state free from suffering. From the perspective of dependent origination, where everything is interconnected, no being in this world can exist independently. It is our thoughts that draw boundaries, but in reality, all beings exist without any boundaries. This is the true nature of the world.

The Most Natural and Easy Path

Let’s examine nature for a moment. When a bird pecks at a fruit, does the fruit think, “Bird, you’re alive thanks to me”? And when the bird eats the fruit and disperses its seeds everywhere, does it think, “Tree, I’ve helped you reproduce tremendously”? They don’t think this way. Similarly, when a cow eats grass and defecates, the manure becomes fertilizer for new grass to grow. Nature works through this mutual support. However, if we look at just one segment of this process, it appears as though one is giving and the other is receiving. When viewed in a limited timeframe or space, it seems like giving and receiving, but when seen as a whole, it’s simply circulation. The reality is that everything is interdependently arising and circulating, merely moving and transforming.

Because we hold onto notions of self, others, sentient beings, and lifespan, it is very difficult for us to understand reality. Even if we understand it intellectually, it’s challenging to put into practice. However, the principles of nature are simple. The word “natural” means easy, doesn’t it? Is smoking natural or is not smoking natural? Not smoking is natural. In other words, not smoking is the easiest. Smoking requires effort in many ways—you need money, you have to go buy cigarettes, you need to light them—it’s complicated. But what about someone addicted to cigarettes? For them, not smoking becomes more difficult. Just like people addicted to cigarettes, we’re in a state where what’s natural actually feels more difficult. However, living according to the Buddha’s teachings is actually the most natural and easiest path.

Sunim concluded the lecture, stating that the explanation of Chapter 4 of the Diamond Sutra would continue in the next session.

Participants gathered in groups to share their thoughts, while Sunim had lunch with the Sangha members in the basement cafeteria. In the afternoon, he attended to administrative work in the office.

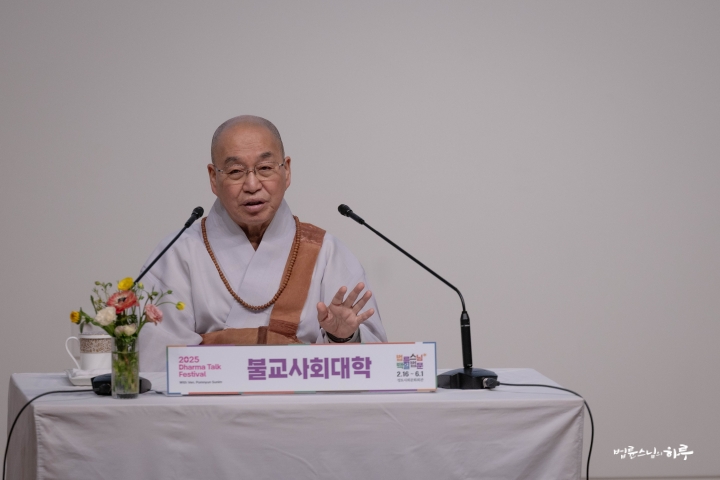

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim delivered the third lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course in the main hall of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center basement. Today’s session focused on learning about the “Middle Way” that avoids extremes, and how to apply this concept to social issues.

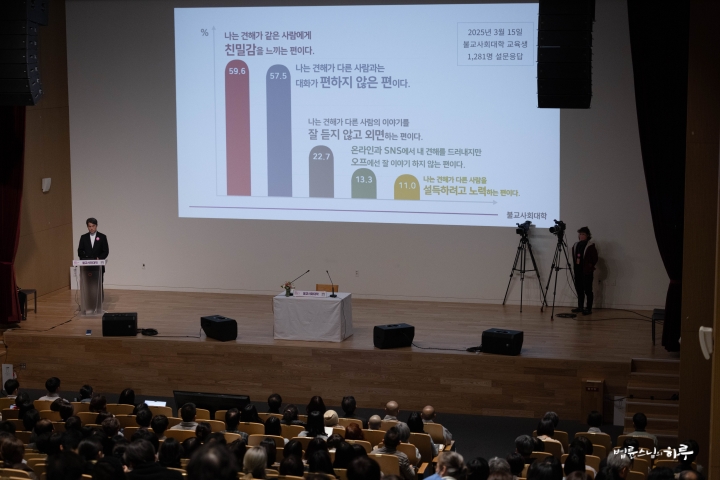

About 200 new students attended the lecture in the basement hall, while approximately 1,900 people joined the online live broadcast. Before beginning the lecture, Sunim collected questions from the new students and their responses, which were shown in a video before the lecture commenced.

After reciting the Three Refuges and the Heart Sutra, the audience requested the Dharma teaching with three bows. Sunim mentioned that the previous lecture on dependent origination might have been difficult to understand as it primarily used examples from nature and science. He then re-explained dependent origination using examples of social issues encountered in daily life.

Sunim explained in detail how various social issues such as economic production and distribution, class formation, neoliberalism, and wealth disparity can be understood from the perspective of dependent origination.

After completing the explanation of dependent origination, he continued with today’s lecture topic, the “Middle Way.”

“Today we will learn about the Buddhist practice principle of the ‘Middle Way’ (中道). This concept didn’t exist during the Buddha’s time; he was the first to discover it. Although the Middle Way uses the character ‘中’ meaning ‘middle,’ it doesn’t simply mean the middle point. The Middle Way is the path that reaches a goal as correctly as possible. It’s like the path an arrow takes when it flies directly toward the center of a target. Here, the character ‘中’ doesn’t represent the concept of ‘middle’ but rather ‘hitting the mark’ (的中). Though we write it with the character for ‘middle’ (中), its meaning is closer to ‘correct’ (正). Therefore, we can say ‘the Middle Way (中道) is the Correct Way (正道).”

The Path That Reaches a Goal as Correctly as Possible

When shooting an arrow at a target, the path the arrow takes differs depending on where you shoot from. The target is one, but the paths the arrows take are all different. Let’s use the example of going to Seoul. If someone asks, ‘How do I get to Seoul?’ If the person asking lives in Incheon, you would say go east; if they live in Suwon, go north; and if they live in Gangneung, go west. The direction to Seoul from each of these conditions can be considered the Middle Way. Apart from these conditions, there’s no definitive answer. This means that without considering the conditions of time and space, nothing can be declared as absolute truth. Another way to express this is ‘No Everlasting Abiding Dharma’ (無有定法), meaning ‘there can be no fixed law.’ You cannot establish something as an unchanging law because it varies according to causes and conditions. Therefore, the Middle Way is, in other words, No Everlasting Abiding Dharma.

In Mahayana Buddhism, “No Everlasting Abiding Dharma” is also expressed as “emptiness” (空). However, if we misunderstand the Middle Way as simply “the middle,” we might think it means compromise. Similarly, if we misunderstand emptiness as “nothingness,” we might think it means non-existence. When we say the path to Seoul cannot be definitively fixed, does that mean there is no path to Seoul? Or does it mean we can take any random route? Neither is correct. Yet we tend to think either that nothing exists or that anything goes. It’s neither non-existence nor arbitrary choice. It means that without specific conditions of time and space, we cannot make definitive statements. However, once time, space, and conditions are established, we can say, “This is the right path.” For instance, if someone from Incheon asks for directions, we can tell them to go east. But even then, if we simply say, “The path to Seoul is emptiness(空),” we would be accused of being lost in fantasy (空想).

The Middle Way: A Perspective That Avoids Extremes

The Buddha was born as a prince and pursued hedonism until he left the palace. Despite what others saw as excellent living conditions, he could not escape his suffering. After leaving the palace, he pursued asceticism. He practiced so diligently that his fellow practitioners looked at him with admiration, thinking he would soon attain enlightenment. However, the Buddha himself was struggling because his suffering had not disappeared. After six years of austere practice, he reflected on his spiritual journey. Having pursued both pleasure and asceticism, he investigated why his suffering remained unresolved. Through this inquiry, he discovered that both paths contained desire. One path followed desire, while the other suppressed it. Desire operates according to certain principles. Following desire leads to consequences. Conversely, suppressing desire creates stress, causing tension in body and mind. How can a state of tension be called happiness? When the Buddha was twelve, he participated in a plowing ceremony and saw a bird eating a worm. Wondering, “Why must one die for another to live?” he found that even his intense ascetic practices did not match the depth and ease he had experienced while meditating under a tree. Despite his dedicated practice, he was gritting his teeth to suppress desire. These two paths, though opposite, share a common feature: they are reactions to desire. For example, if a street vendor tries to pull you into their shop, you either get pulled in or resist stubbornly. The Middle Way, however, is neither being pulled in nor resisting—it’s simply continuing on your own path. It means neither following desire nor suppressing it, but merely being aware of it. You simply notice, “Ah, desire is arising” or “This is pain,” without further reaction.

When our legs hurt during meditation, we often just stretch them out. This is following our desires. Or we grit our teeth and endure the pain no matter how much it hurts. We typically react to phenomena in these two ways. Though these reactions are opposites, they actually stem from the same root. From the perspective of responding to desire, they are identical. Instead of reacting to desire, we should simply recognize desire as desire. When desire arises in a comfortable state, we merely observe it. This awareness is the third path that transcends both extremes. This is the “Middle Way.”

The Buddha discovered this new path and found ease. In that state of comfort, he concentrated fully. The Buddha didn’t discover the Middle Way through enlightenment; he discovered it through reflection. By trying one path, reflecting, then trying another and reflecting again, he discovered the third path—the Middle Way. The Buddha followed this newly discovered path to reach enlightenment. That’s why his first teaching was about the Middle Way. He began by saying, “A practitioner must abandon both extremes.”

Different, Not Wrong

People in this world always insist that they are right. The Middle Way lies beyond these opposing views. That’s why the Buddha always advised against arguing over different positions. Today, our society is polarized toward extremes. If we want to create a peaceful world, we must follow the Middle Way even while holding our own beliefs. In our current society, more and more people are making extreme claims about everything. Everyone insists that they are right. However, to follow the Middle Way, we shouldn’t predetermine anything. This means we shouldn’t jump to conclusions after hearing just one statement, declaring someone right or wrong.

First, we must listen fully to others, understand their feelings, and acknowledge that they are different from us, not wrong. Second, if we can adopt the perspective that “from their position, this makes sense,” our minds remain at ease. A practitioner should always maintain a peaceful mind. Only when I am at ease can I engage in dialogue about the issues.

Does the result of a dialogue need to lead to convergence? Not necessarily. It may converge, or it may not. From a middle way perspective, there can be various solutions. Let’s use the example of going out to eat. If there’s a disagreement between choosing Chinese or Korean food, one day we can accommodate one person by going to a Korean restaurant, and another day we can accommodate the other person by going to a Chinese restaurant. Another option is to order half of each and share. Also, there’s no absolute need to eat together. You could each have an hour of free time where you eat at one place and I eat at another, then meet later at a café. None of these solutions is inherently better than the others. What matters is agreement. Even eating separately is fine if there’s mutual consent. If eating separately seems better, you can peacefully agree to that. Eating separately isn’t bad—it can be a valid solution if both parties agree to it.

When we adopt this middle way perspective, we gain access to many more options. This viewpoint is especially necessary in today’s world where opposition and conflict continue to intensify. Despite our modern society being flooded with information and technological advancement, when it comes to opposition and conflict, we haven’t progressed much from 2,600 years ago. In fact, one could argue that things have gotten worse.

Two Criteria for Buddhism to Solve Social Problems

“To wisely solve social problems going forward, it’s important to have two perspectives. First, we must look at ‘what are the facts?’ from the perspective of dependent origination. Second, when considering ‘how do we solve this problem?’ we must adopt a middle way perspective. The reason we discuss dependent origination and the middle way before specific topics in the Buddhist Social Studies Course is because these two perspectives are what define Buddhism. Whatever we discuss from now on, these two perspectives—dependent origination and the middle way—will serve as our criteria. The middle way refers to following conditions without fixed views, while dependent origination describes how the world actually exists.”

Today was a time to examine Buddhism’s concept of the “middle way” in detail. We concluded the third lecture with plans to learn about the origins of the universe and matter in the next session.

Participants gathered in groups for a sharing session. Through this sharing, they were able to reflect once more on what they had learned today.

Tomorrow will be the 30th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will teach the second lecture of the daytime Jungto Dharma School, followed by an online meeting with Bhutanese government officials in the afternoon to discuss the sustainable development Bon Project. In the evening, he will teach the second lecture of the evening Jungto Dharma School.