Mar 13, 2025 – 25th Day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Sutra Lecture 2, Buddhist Social Studies Course 2

Hello. Today is the 25th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today includes a sutra lecture and a Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to deliver his 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the third-floor Dharma hall, attendees were arranging their seats after finishing the 10 a.m. service. At 10:15, the lecture began with the Three Refuges and the recitation of the Heart Sutra.

About 170 people attended in person at the third-floor Dharma hall, while approximately 550 joined the online live broadcast, and 17 participated from the Haeundae Dharma Center, totaling around 730 participants. After the assembly requested the Dharma talk with three bows, Sunim settled onto the Dharma seat.

Today is the second session of the sutra lecture. Sunim began by summarizing the first chapter of the Diamond Sutra from the previous session before continuing with his explanation of the second and third chapters.

Chapter 2: Subhuti’s Request

“Venerable Subhuti was spending time with the Buddha as usual. They slept together, woke up together, shared meals after alms rounds, and sat in meditation together—just going about their normal daily routine. But this morning, Venerable Subhuti suddenly realized that this ordinary daily life with the Buddha was actually something extraordinary.

In the midst of ordinary daily life, the Dharma was being transmitted to the future.

The great Buddha was sleeping under trees just like them, wearing a kasaya, carrying an alms bowl, returning after alms rounds to eat, putting away his kasaya and bowl, washing his feet, and sitting in meditation together with them. Until now, Subhuti had given no particular thought to this daily routine. But suddenly, the Buddha’s ordinary activities appeared to him as something profound. He realized that the Buddha was constantly protecting practitioners from going astray and silently ensuring that the Dharma would be transmitted to future generations. With this realization, an overwhelming sense of gratitude welled up in his heart. So he rose from his seat, bowed respectfully to the Buddha, and said:

‘How rare, World-Honored One! The Tathagata protects and cares for all bodhisattvas well and entrusts all bodhisattvas well.’

In modern terms, this is praising a truly sacred act. The Buddha responded, ‘That is right, Subhuti! The Tathagata is doing exactly as you have said.’ This shows that while it may seem like an ordinary daily routine, the Dharma is being transmitted through this ordinary life, and the future is also being considered.”

Sunim continued by reading Chapter 3 together with everyone and providing his explanation.

Chapter 3: The True Teaching of Mahayana

“The essence of Mahayana Buddhism is contained entirely within this passage. That’s why this chapter is titled ‘The True Teaching of Mahayana.’ The rest of the Diamond Sutra merely repeats this core message ten or twenty times.

The Diamond Sutra is important for two reasons. First, it silently demonstrates the importance of everyday life. Second, it explains the essential point in just one statement. That is precisely what this chapter, ‘The True Teaching of Mahayana,’ does. However, since the audience cannot immediately understand this, the Buddha goes on to explain it repeatedly with various analogies and explanations in the following chapters.

‘World-Honored One! How should good men and women who have awakened to the mind of anuttara-samyak-sambodhi abide, and how should they subdue their minds?’

This question from Venerable Subhuti asks how bodhisattvas seeking supreme enlightenment should control their minds. The Buddha answers that bodhisattvas who aspire to supreme enlightenment should vow to lead all sentient beings without exception to nirvana. Reading this answer, you might think, ‘Oh, I see,’ and take it lightly, but in fact, this answer contains a tremendous contradiction from our perspective. I’m struggling now because the world doesn’t go according to my wishes. This means I need help from others. Yet when I can barely handle my own life, how can I be told to save all beings in the world? Isn’t this contradictory?

The reason you’re struggling now is because you’re not living your own life properly. When people asked the Buddha, “How can I solve this problem?” he responded by saying that to be free from suffering, you should generate the intention to save all beings who are suffering. It’s like getting more than you bargained for with your simple question. At first glance, it’s difficult to understand why the Buddha answered this way because it’s completely opposite to the conventional perspective.

The Buddha told Subhuti three things: First, generate the intention to save all sentient beings. Second, even after saving all sentient beings, in reality, not a single being has been saved. Third, if a bodhisattva maintains notions of self, person, sentient being, or life span, then they are not a bodhisattva.

Do you understand why the Buddha answered this way? If you do, you don’t need to come to the lecture tomorrow. (Laughter)

If you don’t understand, you should continue coming to listen to the sutra lectures. If you understand this answer, your study is complete. That’s why this content is called Daesŭng Jŏngjongbun (The Orthodox Section of Mahayana). It contains all the core ideas of Mahayana Buddhism. The principles underlying all these teachings—whether it’s Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva going to hell to save sentient beings, Bhikkhu Dharmakara making vows to create the Pure Land and becoming Amitabha Buddha, or Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva vowing, “I will protect and save anyone who calls my name”—are contained within the Orthodox Section of Mahayana. Therefore, it’s not important to move quickly through the material to learn other content. What’s crucial is not just understanding these principles but directly experiencing them.

I’m Suffering Because of My Husband, How Can I Escape?

For example, let’s say someone asks, “I’m suffering terribly because of my husband. How can I live with him and have peace of mind?” What is the religious solution to this problem? It would be for the husband to come home early, listen to what you say, earn good money, and treat you well. That’s why people go to temples or churches, donate money, and pray for blessings: “Please help my husband come to his senses.” This is the religious approach.

Then what is practice? From today, do whatever your husband wants to do. If you do what your husband wants, from his perspective, he was struggling because his wife wouldn’t listen to him, but now that problem is solved. This is precisely how you save your husband.

When we say, “Vow to save all sentient beings,” vowing to save your husband means doing what he wants you to do. If you have this mindset, your husband will feel fortunate to have met such a wife, and his life will blossom. If you do what your children want, they will have no complaints, and the household will become peaceful. In this way, you save your husband, your children, and your entire household.

However, even if your household becomes peaceful, the essence of the Orthodox Section of Mahayana is that not a single person has actually benefited because of you. This is because if you have notions of self, others, sentient beings, or lifespan, you are not a practitioner.

So when you go home today, practice this until our next session. Try practicing with the person who is currently causing you the most difficulty. Whether it’s your spouse, child, parent, friend, or boss at work, if someone is causing you suffering, try listening to their suffering as a way to free yourself from your own pain. Try to cultivate the mindset of doing whatever you can to prevent that person from suffering. This is precisely the way to conquer your own suffering mind. Even if you manage to escape suffering this way, if you still cling to notions of self, others, living beings, and a life span, you haven’t completely freed yourself from suffering. Test whether this is true or false by practicing at home. What matters is not the interpretation but your direct experience.”

Sunim concluded the lecture, promising to explain the third section of the Diamond Sutra in more detail during the next session.

The participants gathered in groups to share their thoughts, while Sunim had lunch with the Sangha members in the basement cafeteria. In the afternoon, he attended to administrative matters in the office.

At 5 PM, Sunim briefly attended the publication celebration for the revised and expanded edition of “Qualifications of a President,” a book by former Environment Minister Yoon Yeo-joon, at the Koreana Hotel on Sejongdaero, where he delivered congratulatory remarks.

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim began the second lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course in the basement auditorium of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. This course analyzes various issues in modern society from a Buddhist perspective and teaches how to address them with the wisdom of practical Buddhism. Today’s session, the second in the series, focused on how Buddhism views the world through the principle of dependent origination.

The basement auditorium was filled with 210 new students of the Buddhist Social Studies Course, while approximately 1,900 people attended via the online live broadcast.

Before beginning the lecture, Sunim shared the results of a pre-lecture survey conducted among the new students, which was presented as a video.

On the topic “The factors that most significantly influenced the successes and failures in my life,” 61 percent of respondents chose “my personal efforts,” showing the highest response rate. The second highest response at 39 percent was “the social and historical circumstances I was born into,” followed by 37 percent selecting “the environment surrounding me,” and 21 percent choosing “support from parents and others around me.”

After reciting the Three Refuges and the Heart Sutra, and following the audience’s three bows requesting the Dharma talk, Sunim began his lecture.

“Today’s lecture topic is ‘How to View the World?’ In other words, I want to discuss the Buddhist worldview. Regardless of country or religion, most religions, thoughts, and philosophies view this world as ‘all things in the universe.’ The term ‘all things in the universe’ means that this world has ten thousand forms. It suggests that this world is a collection of countless individual entities.

How to View the World?

When we view the world as a collection of individual entities, we tend to believe that the disappearance of one entity has little impact on the rest. That’s why various phenomena in the world are expressed as ‘survival of the fittest’ and ‘survival of the strongest.’ Underlying these concepts is the notion of unlimited competition. For unlimited competition to exist, the premise of individual entities must be established.

Additionally, religions typically hold that people who commit sins go to hell, while those who do good deeds go to heaven or are reborn as better beings in their next life. Concepts like hell, heaven, or reincarnation can only exist with the premise of individual entities. There must be a subject who commits sins and receives punishment or rewards. Each entity must possess independence and unchanging characteristics for religions to maintain their doctrines.

The same applies to the material world. Since ancient Greek times, people believed there were fundamental particles that constitute all things in the world. Thus, they named the fundamental particle of matter the ‘atom.’ What, then, did people consider to be the fundamental essence of a living person? In India, this was called ‘atman.’ While the physical body ages, becomes ill, and dies, the soul was considered eternal, capable of going to hell or heaven.

From this perspective, whether in religion, philosophy, or even science, the underlying worldview is that this world is a collection of individual entities. Though expressed in slightly different ways, this can be considered the mainstream worldview.

Why Must One Die for Another to Live?

However, the Buddha discovered that when viewing the world through conventional worldviews, contradictions emerge. At the age of 12, while attending a plowing ceremony, he saw a bird eating a worm and wondered, “Why must one die for another to live?” and “Isn’t there a way for both to live together?” These questions likely arose because he was a youth. From an adult’s perspective, this might have been accepted as natural, without even questioning it.

Most of the education we receive today focuses on winning in competition. Whether it’s learning how to be better at sports than others, how to study better, or how to accumulate more wealth—most disciplines teach methods for winning in competition.

People believe that God created all things in the world and loves humans, one of his creations. So people believe in God and pray for their wishes. But the Buddha questioned: if God grants all wishes, why do people fall ill and die? Why do some kill their own brothers to become kings and live in luxury? If God exists and punishes sin, shouldn’t wrongdoers face consequences? Yet people don’t call such individuals sinners but praise them as great kings. Isn’t there a saying, “Kill one person and you’re a murderer, kill many and you’re a hero”? Steal a little and you’re a thief, steal a lot and you’re a businessman. The Buddha recognized these contradictions in the world.

The Buddha posed these questions to his two teachers at the time. The teachers couldn’t answer and dismissed his inquiries as pointless thoughts. So he had no choice but to find the answers himself. With nowhere else to turn, the Buddha began his investigation. This act of seeking answers is inquiry. This was the starting point of the Buddha’s journey toward enlightenment.

Everything Exists in Interconnection

When the Buddha attained enlightenment and opened his eyes to see the world, it was different from what he had imagined. Before enlightenment, he saw the world as a collection of individual entities, but after enlightenment, he realized that everything in the actual world was interconnected through dependent origination. The term “dependent origination” combines the Chinese characters for “through” (然) and “arise” (起), meaning that everything arises through causes and conditions. In other words, “B arises because of A,” which means A and B are connected. The Buddha realized that all beings in this world are interconnected. It was as if he had previously thought of beads simply placed in a basket, but now understood that the beads were all connected to form a net.

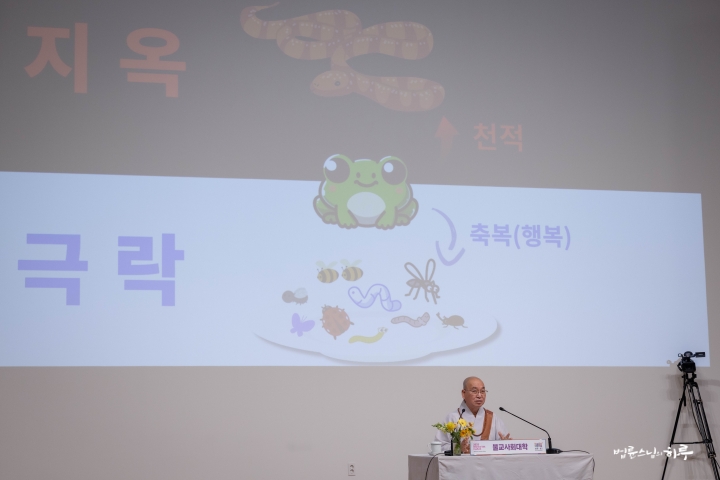

Let’s consider an ecological pond as an example. There are several snakes living around the pond. The snakes eat frogs, the frogs eat insects in the water, and the insects feed on plankton. From the frogs’ perspective, it seemed like there was an endless supply of food in the pond. They thought that snakes were the only thing preventing them from thriving. The frogs believed that if the snakes were gone, they could prosper. So they prayed to a deity to remove the snakes. The deity eliminated all the snakes. With their predators gone, it was like paradise for the frogs, who could now reproduce freely. In this state, from their time perspective, it seemed like they could develop infinitely. Initially, when there were 100 frogs, the number of water insects in the ecological pond far exceeded the number being eaten by frogs. However, as the frog population increased to 500, then 1,000, and continued to grow, the number of insects being consumed by frogs exceeded the number of newly emerging insects. At first, the frogs saw no problem, but suddenly one day, they faced starvation. Such a moment comes in an instant. Everything was fine until yesterday, but you suddenly face a problem today.

Do frogs really only need water insects to survive? Are snakes truly unnecessary beings? Frogs need not only water insects but also snakes for their survival. The presence of snakes ensures the sustainable existence of frogs. However, from a short-term perspective, snakes appear to be a source of suffering for frogs. This creates the illusion that removing snakes would lead to eternal prosperity for frogs. While plankton, water insects, frogs, and snakes may seem to exist independently, when we look at the entire ecological pond, we see that they all harmoniously maintain the phenomenon of life together. This is precisely the law of dependent origination.

The term “law of dependent origination” did not exist before the Buddha. It was first used by the Buddha himself. The Buddha expressed the law of dependent origination in this way:

“When this exists, that exists; when this does not exist, that does not exist. When this arises, that arises; when this ceases, that ceases.”

This means that “this” and “that” are not separate entities but are interconnected. The first statement, “When this exists, that exists; when this does not exist, that does not exist,” expresses spatial dependent origination. All things are interconnected, and nothing exists in isolation or independently. Everything is interconnected within space, and it is because of this interconnection that the concept of space emerges. Therefore, in all that exists, there is no independent self or “I” (atta). Despite this, people insisted on the existence of a self, which is why the Buddha spoke of “non-self” (anatta), meaning there is no independent self. Non-self means that all beings are interconnected, and there is no independent entity.

The statement “When this arises, that arises; when this ceases, that ceases” expresses temporal dependent origination. All phenomena change. It is because of change that the concept of time exists. In those days, when people spoke of God, they thought of something “sacred, eternal, substantial, and blissful.” The term “eternal” is written with the Chinese character “常” (sang). By adding the character “無” (mu) meaning “non-” or “without,” the term “無常” (musang) was created, meaning “impermanence” or literally “without permanence.”

The core philosophy of Buddhism is dependent origination, which can also be expressed as non-self (無我) and impermanence (無常). One explains from a spatial perspective, while the other explains from a temporal perspective, but in reality, these two concepts cannot be separated. In our lives, we cannot exist solely in space or solely in time. Our reality is a combination of both space and time. Einstein’s theory of relativity and theories about the fourth dimension have revealed that time can transform into space, and that all spatial dimensions are interconnected.

Embracing Impermanence Dissolves Attachment

We often use the word “eternal” in our lives: eternal love, eternal life. These things don’t exist. People imagine that in heaven they will enjoy eternal blessings, but that’s not possible. We merely imagine something to be eternal when it lasts for a long time, but nothing is unchanging. You become attached to things because you think they are unchanging; if you knew they would change, you wouldn’t become attached. You become attached to love because you think it’s unchanging, but your feelings when entering the bathroom differ from when you leave, and your feelings at marriage differ from those afterward. Yet you think they remain the same. When couples argue, they often say, “What did you promise me back then?” Such conversations only lead to fights. The feelings then were the feelings then, and the feelings now are the feelings now. You must adopt the perspective of “This is how I feel now, so what?”

There Is No Independent Entity That Is Not Interconnected

Let’s examine what science has discovered about non-self (無我). First, let’s look at the material world. Dalton’s atomic theory stated that atoms are the smallest indivisible units of matter and do not change. This means that atoms exist independently without any internal combinations. All laws of chemical change were established on this premise. For a long time, atoms were considered the foundation of all matter. Atoms are extremely small, with a diameter of 10^-8 meters. In centimeters, that’s one billionth of a centimeter. Because they were so small, these tiny particles called atoms were long thought to be independent entities. Scientists also discovered that there are various types of these independent entities in the world. Research revealed that there are 92 such atoms, which were arranged by weight in the first periodic table.

Later, scientists discovered that electrons exist within atoms. Further research revealed the existence of electrons, protons, and neutrons. They also discovered mesons, which play an important role in nuclear forces, and these are called elementary particles. So are elementary particles the foundation of matter? No. Further research led to the discovery of particles called quarks and leptons. This means that no matter exists as an independent entity. Some might ask if quarks are independent entities, but quarks cannot exist independently. Science has thus far revealed that there are no independent entities that exist in an unbound state.

The principles of the universe’s formation, based on scientific discoveries, follow the same pattern. When we examine how the universe was formed, we see that the origin of matter and the formation of the universe follow the same principles. The microscopic and macroscopic worlds are all interconnected. We have the sun with Earth and other planets orbiting around it, forming the solar system. Many solar systems together form a galaxy, and countless galaxies or mini-universes together form the greater universe.

What about the world of living beings? In the living world, people often used the term “seed.” Rice seed, potato seed—people thought God created seeds separately. However, through science, we’ve discovered that there are genes, and when genes are manipulated, species can change. So seeds are not independent entities.

What about the mental world? The interconnections in the mental world are incomparably more complex and layered than in the physical world. The Buddha researched this mental world and discovered the law of dependent origination, but this law applies not only to our mental world but also to the living world and the physical world. Scientists have revealed the natural connections, while the Buddha revealed the mental connections.

Climate Crisis from the Perspective of Dependent Origination

From the perspective of dependent origination, conquering nature today creates tremendous problems. For example, imagine if feet asked hands, “Please wash me,” but the hands replied, “You’ve never washed me,” and cut off the feet. Both hands and feet are equally parts of the same body.

What would happen if Japan dumped radioactive water from Fukushima? Would it have no relation to us? From Japan, it would travel via the North Pacific Current to the California Current, then the Equatorial Current, eventually entering Korea’s West Sea and South Sea. We would end up eating fish that consumed this contaminated water. Just as food entering our mouth reaches all our organs, nature works the same way. Everything circulates within the Earth, with nowhere else to go.

We must approach how we view the world based on this foundation that everything is interconnected. This leads to completely different solutions than before. In Buddhism, what precedes “compassion”? The term “great compassion of oneness” (dongche daebi) expresses that we don’t pity others as separate entities but feel them as parts of our own body. All Buddhist practices and solutions to social phenomena emerge from this worldview of dependent origination. Without this foundation, social phenomena merely become subjects of debate. Buddhism’s social philosophy is that we should view the world’s problems based on the true nature of existence, which is reality.”

Today’s session focused on examining the Buddhist worldview of dependent origination in detail. We concluded the second lecture with plans to learn about the Buddhist practice of the “Middle Way” in the next session.

Participants gathered in groups for a heart-sharing time. During this sharing, they had the opportunity to reflect once more on what they had learned today.

Tomorrow will be the 26th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will hold a special Dharma assembly commemorating Buddha’s Nirvana Day, and in the evening, he will conduct the Friday Dharma Q&A.