March 10, 2025 – Day 22 of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Sutra Lecture 1, Buddhist Social Studies Course 1

Hello everyone. Today is the 22nd day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. The main lectures of the 100-Day Dharma Talk began today. In the morning, Sunim gave the first Sutra Lecture, and in the evening, he conducted the first lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to give his 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the third-floor Dharma Hall, attendees had finished the 10 a.m. service and were arranging their seats. At 10:15 a.m., the lecture began with the Three Refuges and the recitation of the Heart Sutra.

About 190 people attended in person at the third-floor Dharma Hall, while approximately 550 people joined the online live broadcast. Additionally, 17 people participated from the Haeundae Dharma Center, bringing the total attendance to around 750 people. After the audience requested the Dharma talk with three full bows, Sunim ascended to the Dharma seat.

For the next 12 weeks, every Monday and Thursday morning, there will be “Sutra Lectures” on the Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra. Today was the first session of these Sutra Lectures. Sunim introduced the emergence of Mahayana sutras and the significance of the Diamond Sutra within them, then explained the first section of the Diamond Sutra.

“A Buddhist is someone who takes refuge in the Three Jewels—the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha—and practices the threefold training of precept, meditation, and wisdom. What we are studying today belongs to the Dharma among the Three Jewels. The Dharma consists of three collections: sutras, vinaya, and abhidharma. Our study focuses on the sutra collection. Sutras are categorized into three types: Hinayana sutras, Mahayana sutras, and Tantric sutras. The sutras we will study in our lectures are Mahayana sutras. Traditionally, Mahayana sutras are classified into four categories: Prajnaparamita, Vaipulya, Lotus-Nirvana, and Avatamsaka. The Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra that we will study today belong to the Prajnaparamita category. The Prajnaparamita texts comprise 600 volumes, and the Diamond Sutra is recorded as the 577th text.”

The Beginning of the Diamond Sutra: “Thus Have I Heard”

Let’s examine the background of how these sutras came to be. The process of collecting the Buddha’s teachings after his passing into nirvana is called “compilation.” In the year the Buddha passed away, five hundred arhats who were recognized as having attained enlightenment gathered at the Saptaparna Cave outside Rajagriha. Mahakasyapa presided over the assembly, while Ananda and Upali first recited the teachings, and then everyone chanted together. This process of recalling the Buddha’s words one by one and collectively editing and supplementing them is known as the “First Buddhist Council.” For the sutras, Ananda, who was foremost in learning and had attended to the Buddha, provided the initial drafts. For the vinaya, Upali, who was foremost in upholding the precepts according to the Buddha’s words, provided the initial drafts.

Ananda always began his drafts with “Thus have I heard” (如是我聞). This means “I have heard it this way.” He did not say, “The Buddha said this.” This acknowledges that what the Buddha said and what he heard might not be identical. It simply means “this is how I heard it.” So when Ananda presented his draft saying “Thus have I heard,” the assembly would listen and sometimes confirm it as is, while at other times they would modify or supplement it before finalizing.

One of the Earliest Mahayana Sutras

When the original Diamond Sutra was traced using radiocarbon dating, the oldest version was found to have been created around the 1st century. This is reportedly the oldest surviving Sanskrit original text. Therefore, the Diamond Sutra appears to have emerged between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE. This indicates that the Diamond Sutra is one of the very earliest Mahayana sutras.

Evidence of the Diamond Sutra’s early origin can also be found in its content. While the Diamond Sutra discusses the concept of emptiness, the term “emptiness” (śūnyatā) itself does not yet appear. Additionally, although it mentions bodhisattvas, it does not specifically name any, such as Manjushri or Samantabhadra. In most Mahayana sutras, bodhisattvas ask the questions, but in the Diamond Sutra, it is Subhuti, one of the Buddha’s ten great disciples, who poses the questions. Also, while many sutras set the Buddha’s teachings in celestial realms like Trayastrimsa or Tusita Heaven, the Diamond Sutra is set in the historical Jetavana Monastery. Furthermore, while most sutras feature long monologues by the Buddha, the Diamond Sutra is structured as a dialogue. Most Mahayana sutras describe the Buddha entering samadhi before teaching, but the Diamond Sutra begins with everyday activities without any such descriptions. In these ways, its content closely resembles that of early sutras. This is why the Diamond Sutra is considered one of the relatively early Mahayana sutras.

千二百五十人俱 爾時 世尊 食時 着衣持鉢 入舍衛大城

乞食於其城中 次第乞已 還至本處 飯食訖 收衣鉢 洗足已 敷座而坐

Thus have I heard. At one time the Buddha was staying in the Jetavana Grove of Anathapindika’s Park in Shravasti, together with a large assembly of 1,250 bhikkhus. At that time, when it was mealtime, the World-Honored One put on his robe, took his bowl, and entered the great city of Shravasti to beg for food. After begging from house to house, he returned to his place. When he had finished his meal, he put away his robe and bowl, washed his feet, and sat down.

The first section of the Diamond Sutra describes the background of how the sutra came to be taught. It explains the circumstances under which the Dharma assembly was held. Most Mahayana sutras describe scenes like “When the Buddha entered samadhi, light radiated from the white curl between his eyebrows, flowers rained down from the sky, and the earth trembled.” However, in the Diamond Sutra, it simply states, “When he had finished his meal, he put away his robe and bowl, washed his feet, and sat down.” In modern terms, we might say, “After eating, brushing his teeth, and sitting down for a cup of tea, someone asked a question.” It portrays everyday life in a very simple manner.

The First Section Encapsulates the Entire Content of the Diamond Sutra

This part encapsulates the entire content of the Diamond Sutra. After this, Subhuti, one of the Buddha’s ten great disciples known for his wisdom, asks the Buddha a question, and thus the sutra begins. However, most masters throughout history have considered the first section to be the most important. Although the Buddha’s words begin from the second section, they placed the greatest importance on the first section, which describes the Buddha’s daily life without words. This is because the Buddha’s everyday actions already contain everything we are about to learn.

First, the Buddha puts on his robe, takes his bowl, goes begging, returns, eats his meal, washes his bowl, washes his feet, and sits down… In each moment of sitting and eating, the Buddha is always fully present, here and now. His mindfulness is constantly maintained. Second, when begging for alms, he collects just the right amount of food in his bowl, which shows that he maintains a frugal lifestyle. Third, the Buddha doesn’t live separately in a special way but always stays with the community. He eats together with everyone, shares daily activities, and lives with the community in the same open space in the forest.

Observing the Buddha’s daily routine, Subhuti, who had been living with him all along, was particularly moved that day. He realized, “The Buddha has already been teaching us, without words, how practitioners should live.” He was deeply touched by this realization. Subhuti rose from his seat, expressed his gratitude to the Buddha, and asked the questions that were on his mind. The ancient Zen masters described this as “Subhuti stirring up waves on a calm sea.”

The first section, which describes the Buddha’s daily life, may seem like mere background, but this background encapsulates all the content of the Diamond Sutra that will be expounded later. The first section is about the teaching delivered from mind to mind without words. Then, from the second section, the teaching continued on relieving the suffering of sentient beings through words.

How to Read the Diamond Sutra: What Questions Arise in My Mind?

The entire sutra consists of a dialogue between the Buddha and Subhuti. Sometimes Subhuti asks questions directly and the Buddha answers, or the Buddha calls upon Subhuti to ask questions, to which Subhuti responds, and then the Buddha provides additional explanation. At times, the Buddha already knows what is in Subhuti’s mind and speaks before Subhuti can verbalize his question. We too sometimes have doubts after hearing the Buddha’s words, don’t we? Because the dialogue takes various forms, there are moments when the conversation might seem to make unexpected leaps. You might wonder, “Why does the discussion suddenly shift from one topic to another?” This happens because Subhuti has developed some question about the Buddha’s teaching. If Subhuti were to express his doubt and the Buddha were to answer, the flow would seem smoother. However, since the Buddha sometimes jumps directly to the answer before Subhuti can voice his question, the text occasionally appears repetitive or seems to make abrupt transitions.

Therefore, as you read the sutra, you should always reflect on “What questions arise in my mind about these teachings?” If you do this, the next passage will become clearer. For instance, when it says, “After giving, do not hold onto the thought that you have given,” you might wonder, “What happens if I don’t think about having given? Then why give at all?” This is followed by the teaching that “giving without expectation brings greater merit.” If you ask yourself, “Why does this create greater merit?” you will find the answer in the subsequent passages. This is the format the Diamond Sutra follows.

Sunim concluded the lecture, stating that he would continue explaining the second section of the Diamond Sutra in the next session.

Participants gathered in groups to share their thoughts. Since it was the first day of the lecture, they took time to introduce themselves and also toured the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

After having lunch with the Sangha members in the basement cafeteria, Sunim spent the afternoon working in his office.

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim began the Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture in the main hall of the basement at the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

The Buddhist Social Studies Course is set up by Jungto Society for the first time. It teaches how to analyze various problems in modern society from a Buddhist perspective and how to address them with the wisdom of practical Buddhism. Today was the first session, focusing on understanding the crisis and essence of modern civilization from a Buddhist perspective and learning about the purpose of the Buddhist Social Studies Course. The basement hall was filled with 210 new students, while approximately 1,900 people attended via online livestream.

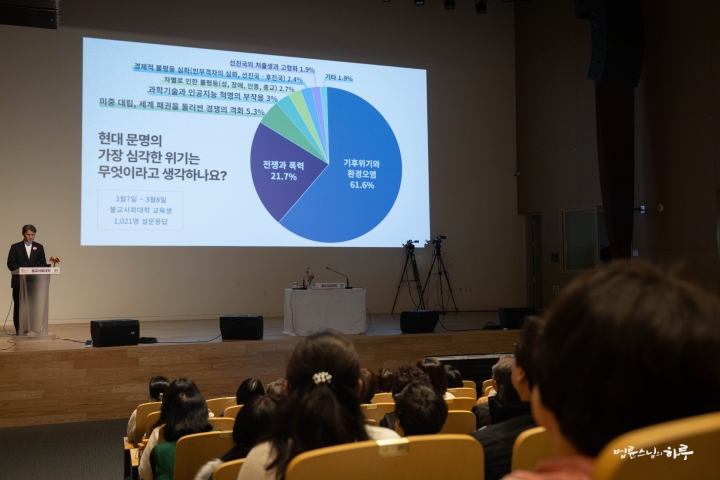

Before beginning the lecture, Sunim reviewed the results of a pre-lecture survey conducted among the new students, which was shown as a video.

When asked about the most serious crisis facing modern civilization, 61 percent of respondents cited the climate crisis and environmental pollution, while 21 percent mentioned war and violence. Other responses included the intensifying competition for global hegemony between the US and China, the side effects of science, technology, and artificial intelligence, discrimination-based inequality, deepening economic inequality, and the low birth rate and aging population in developed countries.

After reciting the Three Refuges and the Heart Sutra, the audience requested the Dharma teaching with three bows, and Sunim began his lecture.

“The world we live in is experiencing turmoil due to many problems. Regardless of religion, nationality, or race, people are putting their heads together to think about, research, and propose solutions to these pressing issues. However, because Buddhism traditionally emphasizes personal practice, there is a lack of perspective on these social issues from a Buddhist viewpoint. As a result, there are very few Buddhist approaches to various social problems. Buddhist books and Dharma talks rarely address social issues. Even among Buddhist followers, there is little activity centered around social problems. This leads to the misconception that Buddhism is not concerned with worldly issues. Ironically, when Buddhists do express interest in worldly matters, some people question, ‘Why would a Buddhist do that?’ or ‘Why would a practitioner be concerned with such things?’ Some even claim that such interest contradicts the pure teachings of Buddhism.

To Understand Buddhist Solutions to Various Social Problems

Why does this phenomenon occur? The reason is that as Buddhism has been passed down through history, the original teachings have been somewhat distorted. First, the Buddhism we encounter is mostly religious Buddhism. For religious Buddhism, how to achieve what I want is important, while the problems of this world are not so significant. Second, we mostly encounter philosophical Buddhism. Philosophical Buddhism primarily discusses ideological content, such as the Buddha’s teachings on non-self or emptiness as the core. Therefore, even when studying philosophical Buddhism, there isn’t much discussion about Buddhist social thought.

So what perspective should Buddhism have on problems occurring in society? The answer can be found by studying the life of the Buddha. This is because we have regarded the Buddha only as an object of faith, not realizing that he was a person who, like us, ate, slept, received criticism and praise, and lived among people.

Among those who lived with the Buddha, some went begging but were criticized and couldn’t get food, and some were even beaten to death. Living with a community of over a thousand people and going out to beg in villages every day, they could hear all kinds of news from the world. Would the Buddha have turned a blind eye to worldly affairs?

Therefore, we need to understand how the Buddha actually engaged with society and history throughout his life. Only then can we gain perspective on how to view the problems occurring in today’s reality.

The core content of the Buddhist Social Studies Course is about how we should view the problems we face now and the various confusions in the world. We are gathered here today to understand the causes of these issues and how to resolve them. I don’t think anyone here wants to write a dissertation for a doctoral degree or teach others. The first goal is to understand how I should live, and the second goal is to establish a direction for how this world should move forward. Today’s lecture has been prepared for these two reasons.

The Path of Saving Sentient Beings Is the Path to Enlightenment

Buddhism views the universe as containing countless worlds. Each world may have good or bad environments, but people live in all of them. Among these, the most pleasant world—where both natural and social environments are optimally arranged—is called the Pure Land of Ultimate Bliss. There is a story about how the Pure Land was created. Long ago, there was a practitioner named Bhikkhu Dharmakara. Seeing the suffering of people in the world, his heart ached, and he asked the Buddha of that time, “Is there no world where sentient beings can live without suffering? Please create such a world.” The Buddha replied, “If you desire it, create it yourself.” So we should be careful what we request. As they say, the one who speaks must take responsibility. (Laughter)

Most of us would have responded, “Oh, how could I possibly do that?” But Bhikkhu Dharmakara thought that the Buddha’s instruction to create it himself was an expression of trust in him. So he answered, “I will gladly try.” But to make a plan, he needed to know what to do. So he asked the Buddha, “Please show me a model.” The Buddha then emitted light from the white tuft between his eyebrows, revealing the entire universe. The sutra says he showed one trillion worlds. Not only was the one who showed remarkable, but the one who saw was also extraordinary. If it were me, I might have looked at just ten worlds and said, “That’s enough,” but Bhikkhu Dharmakara observed all one trillion worlds, both good and bad. Then he made his vows.

“May there be a world without such bad things. May there be a world with such good things.”

In this way, he established forty-eight vows. In today’s terms, it would be like vowing, “May there be a world without climate crisis,” or “May there be a world without gender discrimination.” After countless eons of diligent practice to fulfill these vows, that world was realized. This world is called the Pure Land. Bhikkhu Dharmakara attained enlightenment and became a Buddha named Amitabha. He didn’t create the Pure Land after becoming a Buddha; rather, the process of creating the Pure Land was itself the process of becoming a Buddha. The path of saving sentient beings and the path to enlightenment are not separate—the path of saving sentient beings is precisely the path to enlightenment.

The Process of Creating a Good Society Is Practice

In the Avatamsaka Sutra, there is a passage that says, “For a bodhisattva, the Buddha’s land is not a world that is already completed, but rather a land where the bodhisattva is actively working toward completion.” A bodhisattva is someone who attains enlightenment and follows the path of the Buddha while also saving sentient beings and creating a pure land. For a bodhisattva, the pure land is the land where they are actively working. This means that the moment you set your intention and begin working to create a pure land, that place becomes a pure land for you as a bodhisattva. The pure land is not a completed world. When you are doing your best toward completion, that world is already a pure land for you.

With this perspective, success or failure does not depend on how problems are resolved. If there is something essential for the world, and you are doing your best to fulfill that need, then for you, it is already as good as complete. Objectively, you are moving toward completion, but for you, that process itself is equivalent to the completed world. Therefore, the very process of creating a good society is our practice.

Therefore, Mahayana Buddhist practitioners should not think that they should only practice for themselves, or practice first and then save sentient beings, or create a Pure Land first and then practice. The process of practice is itself the creation of an ideal world, and the activities aimed at creating an ideal world are the path to Buddhahood for individuals. These two cannot be separated, they are not in sequential order, but are unified. In Jungto Society, we call this ‘the unity of work and practice.’ Here, ‘work’ refers to a series of actions carried out with the aspiration to create a Pure Land. If practice is about perfecting oneself, then work and practice are unified.”

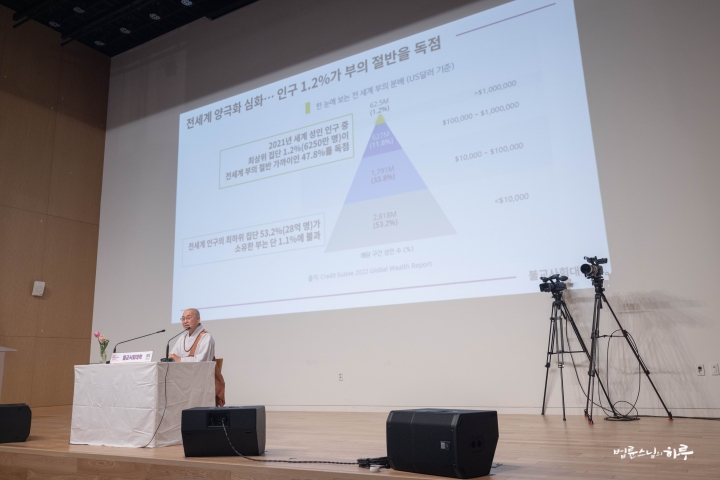

Sunim then gave an overview of the major problems in modern society. He identified climate crisis and environmental pollution as the most serious risk factors, followed by deepening economic inequality, the development of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and robots alongside the collapse of ethics, and the US-China power competition and division in the international community. He explained the damage these problems could cause. Sunim then emphasized the core Buddhist concepts of “Dependent Origination” and “the Middle Way” as solutions to these problems.

Today’s session provided a comprehensive look at how to view society from a Buddhist perspective. The first class concluded after 9 PM, and it will explore how Buddhism can offer solutions to specific social problems through the lens of dependent origination in the coming days.

Participants gathered in groups for self-introductions and to share their thoughts. While some had enrolled because of their interest in social issues, many mentioned that they had learned about social problems through Venerable Pomnyun Sunim. The sharing session provided an opportunity to reflect on what they had learned today.

Tomorrow will be the 23rd day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. The schedule includes teaching the first class of the daytime Jungto Dharma School in the morning, meeting with visitors at The Peace Foundation during lunch, and teaching the first class of the evening Jungto Dharma School.