Mar 7, 2025, Day 19 of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Special Dharma Assembly for Renunciation Day, Friday Dharma Q&A

Hello everyone. Today is the 19th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk, and it is also Renunciation Day, commemorating the day when the Buddha left his palace. In the evening, the Friday Dharma Q&A session was held.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to conduct a special Dharma assembly commemorating Renunciation Day.

In the third-floor Dharma hall, about 150 people had finished their morning prayers and were settling into their seats. The special Dharma assembly for Renunciation Day began at 10:15 AM.

Today is the 8th day of the second lunar month, the day when the Buddha renounced worldly life. Seven days later, on the 15th day of the second lunar month, is the day when the Buddha entered nirvana. Every year, Jungto Society practices with fearless determination for eight days to commemorate these occasions. This year, however, since the 100-Day Special Practice is already underway, it has replaced the regular practice.

The assembly members requested Sunim’s Dharma talk with three full bows. On this Renunciation Day, Sunim spoke about the true meaning of renunciation.

“Today is Renunciation Day, when the Buddha left his palace. What is renunciation? Literally, it means leaving one’s home. You might wonder, ‘Why should one leave home?’ First, let’s consider what ‘home’ means.

First, a home serves to protect us comfortably. It keeps the floor warm to block the cold. The walls block the wind. The ceiling shields us from rain and sunlight. In these ways, it keeps us safe. Second, a home has family—parents, siblings, and children. Third, a home contains various tools necessary for our daily lives. There’s food to eat, clothes to wear, and various household items. A home is arranged to make our lives convenient. Those who leave home are called ‘wanderers.’ A wanderer is lonely without family and uncomfortable without shelter. That’s why wanderers wish to return home.

While a home protects us and allows us to live comfortably, it can also become a constraint. At home, we must listen to nagging, do chores, be mindful of family members’ feelings, and be conscious of neighbors’ perceptions. Ethics and morals bind us. In this sense, home can be described as a constraint.

When we’re at home, we want to leave because of constraints. From childhood, we keep wanting to run away when things don’t go our way. Wanting to leave home is a gesture toward freedom. But as soon as we leave, we immediately become wanderers. We get lonely and try to return home. When we return home, we feel constrained again, and when we leave again, we become lonely. We return home longing for comfort, but once inside, we feel constrained again. This coming and going is called “running away from home.

An Uncertain Life Where Disaster Could Strike at Any Moment

In life, there are times when we think, “This is a disaster. I don’t know what to do.” First, when we’re sick. When we’re so ill that we can’t move, there’s no greater predicament. Second, when we suddenly lose our job. Third, when we lose our possessions. Fourth, when we lose relationships. There’s no greater disaster than losing parents, divorcing a spouse, or losing a child. Losing someone we love feels like being struck by lightning from a clear sky. Fifth, losing reputation or position due to some scandal also feels like a disaster. Imagine drinking too much one night and losing consciousness, only to later discover you unknowingly committed sexual harassment. You can no longer show your face in public. When the story appears prominently in newspapers and on TV news, it’s a major catastrophe.

We constantly live with the anxiety of “What if disaster suddenly strikes?” We can be immersed in happiness thinking, “Ah, I’m so happy!” and then in an instant find ourselves wondering, “Why did this happen to me?” In the scriptures, this is compared to a “burning house.” Our lives are like children playing in a burning house. We don’t know when the pillars will collapse, the beams will fall, or the rafters will come down, yet we’re completely absorbed in playing with toys. That’s what our lives are like. Even power isn’t permanent. It can disappear in an instant. Thus, we live with the anxiety that we could lose something tremendously important at any moment.

A home provides comfort but simultaneously becomes a bondage. However, this comfort is not permanent. It’s like living in a house that could burn down or collapse at any moment. Everything is at risk of disappearing. We live each day hoping for the best. When we clearly see this truth, we can let go of our position even if we currently have one. Then we no longer fear losing that position. If we have wealth but can let it go, we won’t suffer from its loss. If we have honor but release it in advance, we won’t face disgrace later. If we have family but can let them go, we won’t suffer from losing them later.

The Difference Between Renunciation and Running Away

This is why the Buddha left home without clinging to such comfort. “The Buddha’s renunciation” literally means leaving home, but it also signifies departing from family relationships, status, honor, wealth, and everything else. It means leaving voluntarily, not because of some specific reason. “Running away from home” happens when something about the home is unsatisfactory, so one leaves thinking, “Is there a better home somewhere?” After searching and finding no alternative, one returns home, only to feel confined again and run away once more.

Renunciation, however, is like burning down the house as you leave. It means not creating a home to return to. This is “true renunciation.” More precisely, it means “eliminating the home.” Although “running away” and “renunciation” use the same Chinese characters for “leaving” (出) and “home” (家), running away means leaving because you’re dissatisfied with your home, while renunciation means leaving even when there’s no dissatisfaction, recognizing that nothing lasts. Therefore, renunciation can be called a revolution in life. It means completely letting go of all human relationships, values, and everything else you’ve pursued throughout your life. The reason people feel they haven’t made much progress despite practicing for a long time is because they haven’t adopted this attitude of renunciation. They start with limitations.

Renunciation: Letting Go of Everything at Once

Today, the root cause of the climate crisis is excessive human consumption. Energy is used to make clothes, produce food—everything requires energy. Using energy generates carbon dioxide, leading to global warming and the climate crisis. We must either accept these consequences or reduce consumption to address the climate crisis. Yet, far from reducing consumption, we’re actually increasing it. To solve the climate crisis, we need the attitude of renunciation.

On this Renunciation Day, it would be good for all of us to reflect on the true attitude of renunciation. This attitude is necessary to solve the problems of human civilization today and to resolve peace issues. Only by completely letting go of the thoughts of “I” and “mine” and engaging in dialogue can we find a path that benefits everyone. Yet we always clutch onto something, thinking, “I can’t let this go!” That’s why renunciation doesn’t happen.

In the scriptures, during Buddha’s time, people would hear a Dharma talk and immediately renounce the world right there. No one said, “Let me go home and put my affairs in order first.” That’s not true renunciation. Those who feel they need to organize things first have some kind of purpose or goal, thinking, “I want to go to a better place!” If you think, “Shouldn’t I put my past in order before renouncing the world?” you’re still wandering in a dream. The practitioners during Buddha’s time had a clear realization of this contradiction, which is why they could renounce the world on the spot. It’s like waking up from a dream. If you were running an errand for your mother in a dream and then woke up, you no longer need to complete that errand. Yet some people tell me, “Sunim, if you wait just three years, I’ll put everything in order and then renounce the world.” I’ve been hearing this kind of talk for about 50 years now. Not a single one of those people has ever returned. Instead, it’s the people I’ve met by chance on the road who have actually renounced the world.

Renunciation means putting everything down completely. If you keep overthinking, you’ll only get a headache. In today’s world, we need this genuine path of renunciation that penetrates to the essence.

Reasons Why People Cannot Renounce the World

Among those who renounced the world during Buddha’s time, I believe that Venerable Upali’s story has significant implications for us today. Venerable Upali was a barber who cut the hair of royalty during Buddha’s time. The seven princes whose hair he cut were all of royal status and wore expensive ornaments. When Upali saw these princes giving up everything to renounce the world, he had this thought.

“Even those who have everything are renouncing it all to become monks. Why should I, who has nothing, remain here?”

That’s why it was easy for Venerable Upali to renounce the world. From the perspective of giving things up, the less you have, the easier it is to let go. The fact that many of you find it difficult to renounce the world actually means you have a lot of attachments. However, if you have nothing to hold onto, you can immediately renounce the world.

Practice Means Making the Mind Bright, Clear, and Light

Renunciation doesn’t only mean becoming a monk. Whether we’re working toward social justice or moving toward any goal, we must first make a firm decision in our minds to walk that path comfortably and lightly. Otherwise, though we may proceed, we’ll be dragged along reluctantly like cattle being led to slaughter. Those who have become practitioners should have bright faces. Yet often, those who enter temples to practice have darker expressions than people living in the outside world. Why would people who have let go of everything to enter a temple have so many worries?

As practitioners, our minds should be bright, clear, and light. For the mind to become bright, we must move beyond ignorance and cultivate wisdom. For the mind to become clear, we must let go of greed. For the mind to become light, we must set aside our insistence on being right. When the mind feels heavy, it means we are holding onto many assertive thoughts. Even having too strong a sense of mission can make the mind heavy. That’s why many religious people often have heavier minds than ordinary people. Monks and priests often carry heavier minds than the general public. Monks live trapped in the thought that they must always attain enlightenment, while priests live confined by the idea that they must always fulfill God’s mission. Children’s minds remain light because they don’t carry such a sense of mission. When we grasp onto something, our minds become heavy. When we become captivated by something, our minds darken. When we become greedy for something, our minds become clouded. Therefore, it would be beneficial to view practice as maintaining a mind that is clear, bright, and light.

Following the Buddha’s example and letting go of everything is actually the easiest path. There’s nothing difficult about it. Practice is about doing nothing. It becomes difficult when we try to possess something. Trying to smoke cigarettes is hard, but not smoking is actually the easiest thing. You can approach practice with this attitude. The reason your mind feels heavy during practice is because you’re trying to gain something. If your body actually feels heavy, you can rest for a while before continuing. Most of the difficulty in work comes from being trapped in the unwillingness to do it. So try approaching everything with a light attitude. On this Renunciation Day, it would be good to once again cultivate the ‘mind of renunciation.'”

After completing the Dharma assembly, Sunim immediately began the 300-bow practice.

In the third-floor Dharma hall, about 150 people practiced together to the rhythm of Venerable Yusu’s moktak wooden instrument, while Jungto Society members across the country joined in by making bows at home while watching the online broadcast.

After renewing his monastic mindset through the 300-bow practice, Sunim participated in a sharing session.

Following lunch with everyone in the basement dining hall, Sunim spent the afternoon working in his office. He prepared lecture content for the 100-Day Dharma Talk main course starting next week and reviewed his overseas schedule for the latter half of the year.

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim continued with the Friday Dharma Q&A session in the basement auditorium. Many citizens came to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to attend. They completed on-site registration or submitted questions before heading to the basement auditorium with light steps.

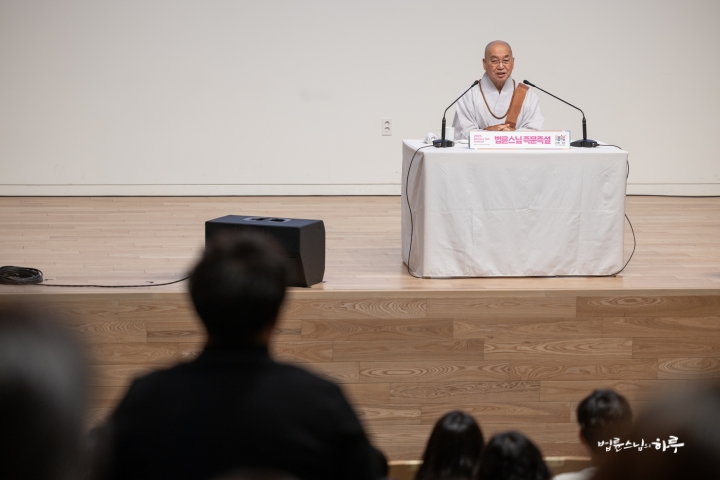

The lecture began with about 5,300 people connected via YouTube and around 100 people present at the venue. After reciting the Three Refuges and Words for Practice, Sunim took his place on stage. He first introduced the purpose of the Dharma Q&A.

“Dharma Q&A is a place where anyone can comfortably ask about their doubts or concerns. Through questions and dialogue, we go through a process where doubts are resolved and suffering disappears. This is not simply a time to explain Buddhist doctrine but a time for conversation to free ourselves from our suffering.”

Sunim then took questions from the audience. Over the course of an hour and a half, six people raised their hands to ask questions.

One person asked two questions. First, he mentioned that while he could comfortably converse with men, he found it difficult to talk with women, and sought Sunim’s advice.

I Find It Difficult to Make Eye Contact and Converse with Women

“Are you married?”

“No.”

“Then it’s because you’re very interested in women and have a strong desire to make a good impression. You speak comfortably with men because you don’t particularly need to impress them, but with women, your desire to look good makes it difficult to speak, and you end up making more mistakes.”

“I try to think of it casually, but it doesn’t work well.”

“Just because I want to make a good impression doesn’t mean the other person will necessarily see me in a positive light. No matter how much I want to look good, the other person will judge me according to their own standards, not considering my intentions. Unless they’re like the Buddha or Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, most people see others in their own way. So if you worry too much about how others perceive you, you’ll become more nervous and end up making more mistakes.

It’s the same with job interviews. Thinking ‘I need to do well in this interview’ doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll actually perform well. Of course, the desire to be liked is a natural emotion and completely understandable. But if that feeling is too strong, it makes you nervous, causing you to stumble over your words or make mistakes. No one has trouble speaking when alone or with close friends or family. That’s because you can comfortably express your thoughts. But when speaking to others, the thought that ‘I need to do well’ makes you more nervous. This is especially true when speaking in front of many people. That’s why people often regret afterward, thinking, ‘Oh, I should have said it this way.’

There are two main ways to solve this problem. First, recognize that the cause of your tension is the desire to make a good impression. When you feel nervous while speaking, acknowledge to yourself, “Ah, I’m trying to look good right now.” Then practice reassuring yourself: “Even if I try hard, the other person won’t necessarily see me in a positive light.” Second, try to increase your experiences talking with women. It might feel awkward at first, but as you become more familiar with it, conversations will flow more naturally. When you talk with different people, you’ll realize that everyone is quite similar, and from that point on, you won’t feel as nervous. Don’t you also get tense when meeting someone of high status, someone wealthy, or someone famous? That’s because you want to establish a good relationship with them. However, you don’t worry at all when passing strangers on the street. It’s important to recognize that the desire to make a good impression creates tension, and gradually develop a more relaxed attitude.

The questioner continued with another question.

How Can I Control My Emotions When I Get Angry at Work?

“Having a quick temper is an innate trait, so it doesn’t change easily. Therefore, you have two options. First, you can express your anger as it comes and accept the consequences. If there are losses, bear them; if you receive criticism, acknowledge it, and each time simply say, ‘I’m sorry. I have a quick temper,’ and move on. Second, you can practice becoming aware when you’re getting angry. Simply resolving ‘I won’t get angry’ isn’t very effective because anger isn’t something you can control with willpower—it’s an emotion that emerges before you realize it. What’s important is recognizing ‘Ah, I’m getting angry now’ when it happens. If you’ve already expressed anger, acknowledge it by saying, ‘I got angry again. I’m sorry,’ and move on. On the other hand, if you were about to get angry but managed not to, simply think ‘That’s fortunate’ and move on. By practicing awareness of your emotional changes rather than trying to suppress anger, you’ll gradually develop the ability to manage it.

While it’s best not to get angry, we often experience anger in our daily lives. It’s important to recognize that expressing anger can cause harm to ourselves. When people commit wrongdoings, punishment creates significant consequences to encourage more careful behavior in the future. Similarly, we need to consider what results our anger might bring to our relationships. Everyone expresses anger differently depending on who they’re dealing with. We tend to show less anger toward those in higher positions and get irritated more easily with family members or close friends. This happens because we believe there won’t be significant consequences when expressing anger toward those close to us. However, even close relationships can be damaged, which is why we need to learn to control our emotions.

There are two best ways to control anger. First, let go of the thought that ‘I am right.’ The fundamental reason we get angry is because we think, ‘I am right, and you are wrong.’ However, it’s not about right or wrong—we’re just different from each other. Second, understand your emotional patterns. If you grew up in an environment where your parents or family members easily got angry, you likely absorbed that atmosphere naturally. If that’s the case, you need to become aware of those patterns and make efforts to gradually change them.”

“Thank you. I understand now.”

By the time the conversation ended, it was past 9 PM. Following the guidance of the volunteers, the audience gathered in the main hall dispersed and headed home. Sunim expressed his gratitude to the volunteers for their hard work before making his way to the Jungto Center.

Tomorrow will be the 20th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will give a Dharma talk during the 1080 prostration practice, and in the afternoon, he will conduct the initiation ceremony for Balsim Practitioners (Junior Jungto Practitioners) of Jungto Society.