Feb 22, 2025 – Day 6 of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, 1080 Bows Practice, Jungto Dharma School Graduation Ceremony

Hello. This is the sixth day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today is a day for practice, reflecting on the Dharma teachings heard over the past week.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. On the third floor in the Dharma hall, many members of the Sangha were participating in the 9 a.m. morning prayer, offering sincere prayers.

After the morning prayer, the hall was tidied up, and at 10:15 AM, the 1,080 bows practice began. About 230 people filled the hall to participate in the practice.

Before starting the practice, the participants requested a Dharma talk from Sunim with three bows. Sunim gave a talk on the mindset one should have when engaging in practice.

“Today is a day for practice, reflecting on the Dharma teachings heard over the past week. To engage in practice, you need to have two mindsets.

Mindset for Practice

First, you should keep your mind at ease. You shouldn’t be overly tense or lazy. When I observe you practicing, I sometimes see you becoming a bit tense or feeling rushed to complete the bows quickly. When your mind becomes tense or hurried, you need to relax and let go of that urgency. This is not a 100-meter sprint where you need to finish quickly or boast about being the first to complete 108 bows. Practice is not about showing off your strength.

Second, you must be consistent. You should practice whether you want to or not, whether the practice is going well or not. Only practicing when you feel like it and stopping when you don’t, or feeling good when it’s going well and quitting when it’s not – that’s not true practice. Practice means not being swayed by whether it’s going well or not, whether you want to do it or not, whether it’s difficult or not. If you’ve decided to do it, continuing steadily is what practice is about. However, many of you often force yourselves to practice when you don’t want to. If you’re just pretending to bow once while others bow twice, or trying to exert as little effort as possible just to pass the time, that can’t be called practice.

You shouldn’t be overly tense, but you shouldn’t be lax either. You shouldn’t be too hasty, but you also shouldn’t be lazy with an attitude of ‘whatever will be, will be.’ You should maintain a steady pace that you’ve set for yourself while staying relaxed. You should continue even when your legs hurt, even when it’s difficult.

How to Manage a Fluctuating Mind

The nature of the mind is to constantly fluctuate. At times, we may feel reluctant to practice, then suddenly feel motivated, then think, “Ah, let’s do it,” only to question, “Why am I bowing?” The mind is always going back and forth like this. When we’re in love, we might feel like giving everything to the other person, but when we’re angry, we might feel like killing them. This shows that the mind is not constant; it fluctuates. This is why the mind is considered impermanent (無常). It’s not reliable. Yet, we often problematize the inconsistency of our minds. Is it wrong for the mind to fluctuate? No, it’s not. This is the inherent nature of the mind. In the Satipatthana Sutta, this is expressed as ‘observing the impermanence of the mind’ (觀心無常). It means that when we observe the mind as it is, we see that it constantly changes like boiling water, without any permanence, in response to various stimuli. Once we realize this, we can remain unperturbed regardless of how the mind manifests.

There’s no need to consider it good when the mind is calm or bad when it’s active. The mind doesn’t arise and disappear according to our intentions. It’s influenced more by the unconscious, or karma, than by our conscious will. Therefore, by carefully observing our mind, we can understand how our karma has been formed. We should let the mind be as it arises. There’s no need to think, “I’m practicing very well right now” when we feel motivated, nor should we think, “My practice isn’t going well” when we feel reluctant. The mind, by nature, fluctuates.

Practice Even When You Don’t Want To, and Just Do When You Want To

When you perform prostrations, your body naturally becomes tired and exhausted. This is a given from the start. It’s not just 108 prostrations, but 1,080, so it’s bound to be challenging. For example, let’s say you’re climbing Mount Seorak. You start off in good spirits, but halfway up, you become exhausted and start to regret it. Thoughts like “Why am I putting myself through this? Should I turn back now?” constantly arise. That’s why most people turn back if they’re alone. However, when you go with friends, you might start off leading the way, but later end up reluctantly continuing, mindful of your friends’ eyes on you, as like biting the bullet. Similarly, when practicing intensive meditation, physical discomfort is a given. Moreover, if a friend persuaded you to go or your mother forced you, the resistance becomes even stronger. That’s why you shouldn’t start intensive practice due to external pressure. It gives you excuses to blame others. However, all of this is predetermined from the moment you make your choice. When you do prostrations, you sweat a lot, your legs hurt, countless thoughts of not wanting to continue arise, and you feel regret. You should start knowing that these are all expected occurrences.

Why do we practice diligently? We practice diligently precisely because we feel reluctant to do so. Diligent practice means consistently carrying on despite the arising of unwillingness. If you found bowing for two hours enjoyable and pleasant, it would be considered play rather than diligent practice. Instead, diligent practice involves persevering steadily without being swayed by the frequent occurrence of reluctance and difficulty.

When doing 1,080 bows, you might feel tired around 300 bows, then again at 700 bows, but if you overcome these hurdles, it becomes manageable. Completing all 1,080 bows within the given time can bring a sense of satisfaction, while failing to do so might lead to self-disappointment. However, whether you completed exactly 1,080 bows or missed one isn’t particularly important. Some people try to rush through the bows, performing them carelessly. There are those who merely pretend to bow, lifting their hips without touching their heads to the ground. If that’s the case, I wonder why they bother bowing at all. (Laughter)

Even if you can’t complete all the prostrations, you should press your buttocks firmly against your legs and perform each bow sincerely before standing up. Lying prostrate for a long time before getting up is not a sincere practice. It’s just pretending to be sincere while actually avoiding the effort because you find it difficult and unpleasant. I know your minds inside out. How? Because I used to do the same thing when I practiced 10,000 prostrations in the past. When you’re tired, you pretend to be sincere while lying down, but if you do prostrations this way, you won’t feel refreshed afterward. When you put in sincere effort and consistently do prostrations, the process may be challenging, but after finishing, you’ll feel a sense of accomplishment for overcoming yourself. First, you’ve conquered your body, which naturally feels tired from prostrations. Second, you’ve overcome the mind that keeps resisting due to physical discomfort.

I See This Feeling Arising Because It’s Difficult

As you accumulate experiences of overcoming reluctance, you’ll be less likely to hurt others by immediately voicing your emotions when making friends, dating, or in married life. This is because you’ll be able to pause each time you feel angry. When something unpleasant happens at work, you might feel like quitting on the spot and saying a few choice words to feel better. But the next morning, you’d regret it, thinking, “I should have held back for a moment.”

However, if you practice diligently, you can overcome unpleasant feelings and difficult emotions on your own. It’s not about forcing yourself to endure, but rather recognizing your own mind and voluntarily accepting and overcoming difficulties, which prevents emotional scars. When you choose to go hiking, even if it’s extremely challenging, it doesn’t leave a scar because it was your choice. But when you’re forced to do something, that experience can leave a lasting emotional wound.

That’s why practice should be based on voluntariness. You must choose to start on your own. You should begin knowing that there will be challenges along the way. This way, even when difficulties arise, you won’t be swayed by them. But if you force yourself, your mind will constantly be influenced by external circumstances. This is because the nature of the mind is to continuously create excuses and look for reasons to quit. Thoughts like “Should I stop after this one?” “Why am I doing this?” or “Should I say I have a stomachache and leave?” keep arising. At such times, it’s important to observe yourself having these thoughts. Instead of suppressing them by thinking “I shouldn’t feel this way,” recognize them by noting, “I see this feeling arising because it’s difficult.”

When you look back after completing your practice, the difficult moments will seem like a midsummer night’s dream. When challenging thoughts arise, they feel incredibly important, but in retrospect, you can barely remember them. Just as everything seems significant in a dream but is hardly remembered upon waking, these are what we call delusions. In the end, they’re just passing phases. The key is not to get caught up in each moment, but to observe them, thinking, “I see this feeling arising because it’s difficult,” and move on.

Not Rationalizing Oneself

It’s quite interesting to observe how our own mind works. We can see that when our mind is troubled, it tries to make excuses and escape from the situation. The mind always tries to protect itself. Even when we do something wrong, we come up with reasons to justify our actions. We say things like, “I had no choice but to do this because you did that.” We’re always looking for excuses. Look at the current political situation. Even when actions violate the constitution, some argue, “Don’t question the declaration of martial law. There were conditions that made it unavoidable.” Despite breaking the law, they insist that we should focus more on why they had to make such a choice rather than the act itself. This attitude isn’t unique to certain individuals; in fact, all humans possess this trait. It’s not because humans are inherently bad, but because the mind has a natural tendency to justify itself.

That’s why in this world, no one thinks they’ve done wrong. Everyone believes they’ve done the right thing from their perspective. They think they had no other choice. Of course, some people do say, “I was wrong.” But even this is ultimately for their own benefit. They calculate in their minds that it’s better to admit fault and avoid conflict rather than insisting they were right. So they apologize, but cases of genuinely acknowledging wrongdoing are extremely rare.

This is how humans constantly rationalize themselves. Because this is human nature, we don’t need to be particularly annoyed when others justify their actions. However, this doesn’t mean we should rationalize our own behavior. We practice to overcome this tendency. The reason practitioners shouldn’t rationalize themselves is that overcoming this habit is necessary to reach a state free from suffering. We need to adopt an understanding attitude towards others, thinking “They could have their reasons,” while viewing our own tendencies as “This is what I need to overcome.” First, we should be aware of any thoughts that arise without judging them. Second, it’s important to practice diligently to overcome these thoughts without being swayed by them.

When You Keep Bowing Your Body, Your Mind Follows

Bowing is a practice of humbling oneself. When we think highly of ourselves, our heads naturally lift, and when we feel apologetic, our heads naturally lower. So, touching our forehead to the ground is a way of expressing, “I am lacking.” When we humble our minds, our bodies naturally bow, and when we keep bowing our bodies, our minds follow suit. So, try to humble your mind while also bowing your body. Even if your mind doesn’t follow at first, start by bowing your body with the attitude of “Let’s start with the body first.” When it’s hard, your mind may resist. At those times, try to overcome that resistance. Don’t be impatient, but practice steadily.”

Next, the 1,080 prostrations practice began.

“With a broad and deep vow, we practice the bodhisattva path to save all suffering beings. We sincerely take refuge in Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva…”

Everyone chanted loudly and prostrated to the rhythm of the moktak (wooden instrument). With each bead of the prayer beads turning, sweat formed on their foreheads.

Amidst the continuous sound of the moktak, it took three hours to complete the 1,080 prostrations. With their bodies drenched in sweat, they concluded the practice with the Four Great Vows.

“May all beings attain Buddhahood.”

Due to knee pain, Sunim couldn’t join in the prostrations and moved to the Jungto Center. After lunch, at 2 PM, the online graduation ceremony for the Jungto Dharma School began.

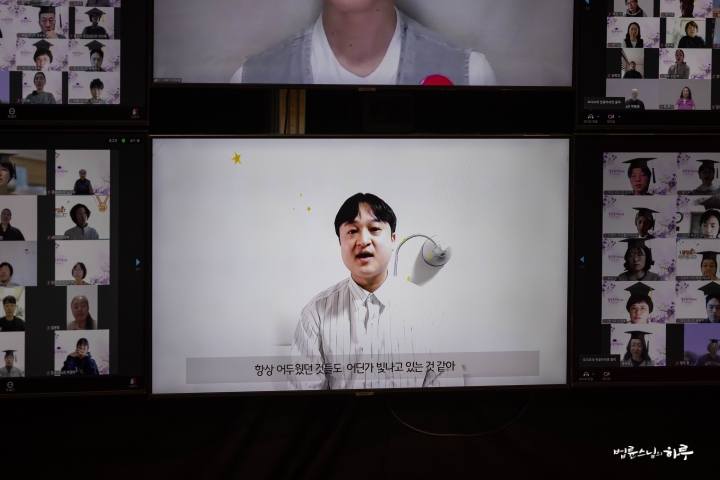

Today is a meaningful day as students complete five months of study and move towards a new beginning. Most graduates watched the live broadcast together in their classrooms, while those receiving perfect attendance and diligence awards gathered in the video conference room.

After listening to the congratulatory speech by the President of Jungto Society, they watched a celebratory performance and a video showcasing the Dharma School classes and practical activities over the past five months.

Then, Sunim, as the Dean of the Jungto Dharma School, presented diplomas to about 1,500 graduates from Korea and abroad.

“I present you with your diploma.”

“I have received it well.”

Applause erupted from the video conference room.

“Congratulations to all of you.”

Following this, 166 people received perfect attendance awards, and 189 received diligence awards.

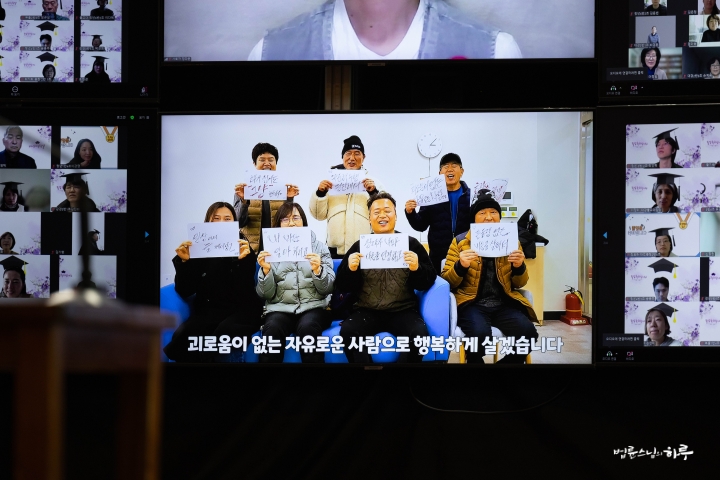

Amidst the applause, two graduates shared their reflections.

“My suffering began when I started my doctoral program. I was consumed by impatience, anxiety, and fears about the future. However, as I listened to Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s lectures at the Jungto Dharma School, I gradually began to feel lighter. Through the Youth Unification History Tour in Gyeongju, the 1000-Day Practice prayer, and the Awakening Retreat, I gained many insights. Through all of these experiences, I realized what I had been attached to and what had prevented me from seeing beyond. Once I understood this, I was able to let go of all my resentment, hatred, and anger. I learned that everything originates from me and returns to me. I’m still surprised when family, friends, and fellow practitioners tell me that my expression looks brighter. It’s amazing how changing my mindset and perspective on situations has reduced my suffering so much. I don’t think I’ve ever felt this light in my life. To maintain this joyful realization and lightness of heart, I plan to enroll in the Sutra Course and continue my practice diligently to become a person who can be of good use. I am sincerely grateful.”

“I started the Dharma School classes with a light heart, having just quit my job and taking a break. Over the past six months, these classes have given me countless exclamation marks, question marks, and commas in my life. After attending the Dharma School, for the first time, I engaged in 108 prostrations of repentance prayer, rather than praying for my wishes to be fulfilled. I realized that I had been creating an image of ‘how my child should be’ and getting angry when my child deviated from it. I understood that when viewed through my own standards, it seemed wrong, but when seen as it is, there was nothing that needed to be corrected in my child. At that moment, it felt as if an exclamation mark in the shape of a bamboo stick struck me, jolting me to awareness. Learning about the life of the Buddha also raised questions. I began to question the gap between the compassionate Buddha I had relied on since childhood and the human Buddha I learned about in the Dharma School. I also developed a desire to understand the meaning of the sutras I had been reciting without understanding. After learning about the Middle Way, I constantly questioned what constitutes the Middle Way when applying and practicing it in daily life. I still get angry, and my stubbornness and prejudices still pop up unexpectedly. However, I can now pause briefly instead of losing control. I practice meditation regularly, becoming aware of my breath and body condition. Now, before blaming others, I take a moment to breathe and try to see things from their perspective. I express my sincere respect and deep gratitude to Venerable Pomnyun Sunim for teaching these lessons.”

Listening to the stories of those who experienced life changes through the Jungto Dharma School, we were once again reminded of the preciousness of encountering the Buddha’s teachings. The graduates sang “The Grace of the Teacher” together, expressing their gratitude to Sunim for guiding them with the right Dharma.

Then, the graduates requested a Dharma talk from Sunim with three prostrations. Sunim spoke about the importance of continuing a life of practice, giving, and service to maintain a connection with Jungto Society after graduation.

“I sincerely congratulate all of you who have graduated from the Jungto Dharma School. Today, let’s talk about what perspective we should have as we graduate from the Dharma School.

Why Do We Regret and Suffer After Making Choices We Like?

In life, we all live according to our own preferences. On the surface, we might blame others for our circumstances, but ultimately, we all live in our own way. However, even after choosing what we like, we later regret and suffer. Did anyone force you to date? People are overjoyed when they start dating, but later suffer because of it. They receive congratulations for getting married, but then suffer when married life becomes difficult. They are congratulated for having a child, but then suffer because raising a child is challenging. They receive congratulations for opening a store, passing an exam, or getting a job, but when these things become difficult, they suffer again. That’s why I don’t congratulate people when they say they’re getting married. I just say, “Is that so?” I can’t say “Congratulations” because I know that soon enough, they’ll be complaining about how difficult it is.

This is even true for our country’s past presidents. Everyone is happy when they are elected, but by the end of their term, either they themselves end up in prison, or their children or close associates do. Whenever this happens, I wonder, ‘Is the presidential election about choosing who will go to jail next?’ They choose this path themselves and even receive congratulations, but ultimately end up in misery. Regarding this, the Buddha said, ‘Pleasure is suffering.’ Our lives are a continuous cycle of suffering and pleasure. This means that pleasure cannot last forever. The more pleasure we experience, the more suffering we will inevitably face later. However, the Buddha’s teachings show us how to attain sustainable happiness without suffering. This state of sustainable happiness without suffering is called ‘Nirvana.’ The goal of practice is to attain Nirvana.

So why do we suffer? It’s because of our ignorance. If we awaken to our ignorance, we can move towards a state free from suffering. This ignorance can be broken down into three categories: desire (貪), anger (瞋), and ignorance (癡). When we become excessively greedy or act on our impulses, suffering inevitably follows without us even realizing it. That’s why people have long said, ‘Blinded by greed’ or ‘Seeing red with anger.’ Greed and anger ultimately stem from a lack of understanding (ignorance). In other words, ignorance is the root cause.

Three Practices for a World of Shared Happiness

Therefore, Jungto Society practices three things to help many people free themselves from suffering. First is practice. Practice means maintaining ‘awareness’ to free oneself from suffering. The Buddha found this path on his own and reached a state free from suffering. He also guided those of us who are suffering, showing us the way so that we too can reach a state free from suffering by following his teachings. The self-enlightened Buddha spread teachings to guide suffering beings to a state free from suffering. And suffering beings, following the Buddha’s teachings, practiced diligently and finally reached a state free from suffering. Because these three are most important, we call them the Three Jewels (Sambo). Practitioners should take refuge in the Three Jewels of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and cultivate the threefold training of precept, meditation, and wisdom as taught by the Buddha.

Second is volunteering. We should dedicate some of our time to volunteer works for others. Instead of always selling our talents for money, we should share and give them freely.

Third is giving. Even if it’s wealth I’ve earned through my own efforts, compared to poor people, it may be that more has been distributed to me. So we need to practice giving with the mindset of ‘This belongs to you’ and returning it.

When we adopt an attitude of practice, volunteering, and giving, we can walk a path that brings happiness to ourselves and peace to the world. This is called ‘sanggu bori, hahwa jungsaeng’ (上求菩提, 下化衆生). It means seeking happiness and freedom for oneself above, and pursuing freedom and happiness for others below. Those who live such a life are called practitioners, or ‘bodhisattvas’. You have diligently learned these concepts over the past five months, so from now on, you should move forward step by step in this direction. When you do so, you too can be called a practitioner, a ‘bodhisattva’.

A Path Walked Together, Not Alone

Jungto Society is a community of people walking this path together. We join hands with fellow practitioners and walk together because if we go alone, we might give up. Based on the perspective that practicing for 100 days allows us to understand our state, and practicing for 1000 days can transform us, we call practicing together for 1000 days the ‘1000-Day Practice’. If possible, I hope you will participate in the 1000-Day Practice and continue your practice together.

Now, upon graduating from Jungto Dharma School and becoming a member of Jungto Society, you are qualified to participate in the following activities. First, you can attend the Weekly Dharma Assembly every Wednesday. You can become a Jungto practitioner who listens to Dharma talks and practices meditation, volunteering, and giving weekly. Second, by participating in the 1000-Day Practice, you can practice together at 5 AM every day and gather once every 100 days to review your practice. Third, you can participate in meditation retreats held in the first and second half of the year for intensive practice lasting 4 nights and 5 days or 6 nights and 7 days. Fourth, you can participate in the ‘Awakening Retreat’ to directly experience and realize what you have learned so far with your body and mind. After the ‘Awakening Retreat’, you can experience recognizing your subtle mind through the ‘Sharing Retreat’. Fifth, you can participate in pilgrimages to sacred sites in India, following in the footsteps of the Buddha and having another opportunity for self-reflection. And to develop pride as a citizen of the Republic of Korea, you can also participate in the Northeast Asian History Tour, visiting historical sites of the independence movement and the Goguryeo and Balhae dynasties. Since you can participate in these meaningful activities together, I hope you will join as a member of Jungto Society and continue your practice steadily.”

After concluding the Dharma talk, Sunim continued to listen to the reflections of the graduates. As one person pressed the raise hand button, many graduates followed suit, raising their hands to share their thoughts.

“I work as a taxi driver and used to be a very angry person. After attending the Jungto Buddhism Course, my anger has significantly subsided. Sunim, thank you.”

“After graduating, I find myself saying ‘This is fine, that is fine’ much more often than before. During practical activities, I frequently said ‘Okay, let me try that again,’ which has been very helpful.”

“The biggest change for me is developing a habit of reflecting every time anger arises. I will continue to follow Sunim’s teachings closely.”

“When panic disorder and depression suddenly struck me, I enrolled in the Jungto Buddhism Course as a last resort. By internalizing Sunim’s teachings, I now live very comfortably.”

“I used to be a person with excessive anxiety. After listening to Sunim’s Dharma talks, my anxiety has greatly diminished. I plan to continue my practice by enrolling in the Jungto Sutra Course.”

“I encountered Sunim’s teachings during an extremely hard time after sending my mother, who had been battling alcohol addiction, to heaven. Now I understand my mother, and as I’ve come to understand myself, my mind has become much more at peace.”

It was touching to see Sunim’s words about the goal of the Jungto Buddhism Course – progressing towards a life without suffering – manifesting in each person’s reflections. Finally, Sunim gave a closing remark.

“Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I look forward to meeting you again when you enroll in the Jungto Sutra Course.”

The graduation ceremony concluded with the Four Great Vows. The students entered the course website to continue sharing their thoughts in their respective classrooms, while Sunim left the broadcasting room.

As the sun set, Sunim spent the evening proofreading manuscripts and handling various tasks before concluding the day’s activities.

Tomorrow marks the seventh day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will conduct a meditation retreat in the Dharma hall on the third floor of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. In the afternoon, he will preside over the graduation ceremony for the Jungto Sutra Course. In the evening, Sunim will consecutively attend online regular board meetings for the Jungto Society chapters in Germany, New York, and New Jersey.