February 10, 2025 – 7th Day of Trongsa Survey in Bhutan (Kella, Bagochen-bulingpang)

Hello. This is the 7th day of the Trongsa survey in Bhutan. Today, we visited Kella Chiwog in Tangsibji Gewog and Bagochen-bulingpang Chiwog in Nubee Gewog in the morning. In the afternoon, we had a meeting with senior officials of Trongsa Dzongkhag to summarize this survey.

After his morning practice, meditation, and breakfast, Sunim left the accommodation at 7:30 AM for Kella Chiwog in Tangsibji Gewog, which was two hours away.

Kella Chiwog was not originally included in this survey plan. While checking the survey area on the map, Sunim discovered a village across the river and suggested visiting it. When asked, the Trongsa administrator said it was not included in the itinerary because it was far from the planned route and would take a long time to reach due to the lack of roads. Sunim proposed adjusting the schedule to survey Kella Chiwog, which led to today’s sudden visit. The steep mountainside was covered with terraced fields and paddies cultivated by people over many years.

After a two-hour drive through mountain roads lined with dense fields and paddies, we arrived at the entrance of Kella Chiwog. When we reached a steep section impassable by car, Sunim and his group proceeded on foot into the village.

Soon, we saw thick smoke from burning juniper, and through the smoke, we could see the villagers waiting for Sunim.

Sunim gave a Bhutanese-style blessing to the welcoming residents and entered the classroom of Kella Primary School, where today’s meeting was to be held. After performing a traditional welcome ceremony, the residents presented their prepared offerings to Sunim one by one. The classroom was filled with offerings, and residents were seated closely together.

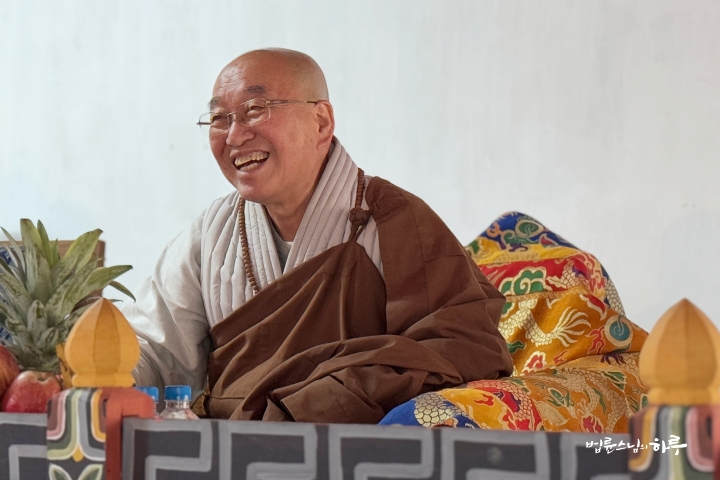

Sunim began the conversation with a warm greeting.

“First, I take refuge in the Three Jewels – the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. You have offered so much. May all those who have made offerings receive the blessings of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, be healthy, and succeed in all their endeavors. This meeting was arranged suddenly due to my request. Was it inconvenient for you to gather on such short notice?”

The villagers responded in unison:

“Not at all, Sunim. We were overjoyed to hear that you were coming. We are grateful that you came to visit us.”

After the Tshogpa (village leader) spoke about the current situation of the village, Sunim continued the conversation.

“The Tshogpa just mentioned only one issue – the need for a road. Now that I’m here, I can clearly see the need for a road. However, if you wait a little longer, the government will address this issue. Projects like electricity, roads, and bridges are all part of government initiatives. But because the government has a limited budget, they have to consider the needs of all of Bhutan, which means things might not progress as quickly as you’d like. While you find the road to Kella village inconvenient, as I traveled around Zhemgang, I saw many places where roads don’t even come close to the villages. Yesterday, people in Nubee Gewog said they needed their road paved, even though they already have a road. Some villages need roads built, while others need existing roads paved. The government can’t do everything at once.

I have inspected the road conditions all the way to Kella village. I fully understand your need for better roads. However, I ask for your patience. According to the Gup (village leader), construction will begin soon. Whether it takes one year or two, please bear with the inconvenience a little longer and wait.

The reason I came here is to see how you live. Bhutan has done well in preserving its traditional culture and natural environment. However, this can sometimes make life inconvenient for residents. That’s why I’ve come to meet you, to see if we can make your living environment more convenient and clean.

Sunim spent 30 minutes explaining the ongoing JTS projects in Bhutan. Then, the Tshogpa shared the difficulties faced by the residents.

“As you can see, Kella village is remote. The other four chiwogs in Tangsibji Gewog are better off than Kella village. In Kella, many people use traditional outhouses due to a lack of proper toilets, and many live in temporary housing. All the paths within the village are dirt, and the water supply used by 35 households needs repair. One reason for the poverty in Kella village is that people don’t own their land and have to give most of their harvest to the monastery that owns the land. They grow rice, but most of the land belongs to the Trongsa Sangha. Since they have to offer most of their harvest to the Sangha, they have no surplus beyond subsistence. There are also people with disabilities in the village. Some are visually impaired, and others have mental health issues. They need protection. The residents of Kella Chiwog are in a much more difficult situation compared to other chiwogs.”

After listening to the Tshogpa’s explanation, Sunim explained how to address the issues of people with disabilities.

“There are facilities in eastern and western Bhutan that care for people with specific disabilities. Ideally, such facilities should be available in each district so that families can visit frequently. However, due to Bhutan’s small population, there is one in the east and one in the west. As far as I know, if anyone among you has a disability, you can report it to the government and immediately enter a facility for people with disabilities. Elderly people without the ability to support themselves can apply for support at elderly welfare facilities run by the king. However, as I’ve traveled around, I’ve noticed that villages often have people struggling with disabilities who aren’t well-connected to these facilities. While the central government says that facilities for people with disabilities and the elderly are guaranteed and that they will be protected once registered, in the field, many requests for protection of people with disabilities and the elderly are made to JTS. I ask the Tshogpa to report these circumstances so that they can be registered in Zhongkhar. If that doesn’t work, JTS will make plans to provide support.”

“Yes, I understand.”

Sunim then asked specific questions to the residents to assess the village’s situation, such as how many households were without homes. In Kella Chiwog, there were seven households without homes. Usually, there were only one or two extremely poor households without homes in a chiwog, but here there were seven. Sunim asked each person why they had been without a home until now. There was a woman with three children who couldn’t build a house because she was divorced from her husband, and an elderly person who had an old, dilapidated house but couldn’t repair it.

Next, Sunim asked if there were people who had homes but with poor indoor facilities.

“Please raise your hand if your indoor facilities are really poor and need to be fixed. Is there anyone who needs to fix their toilet or kitchen, or needs to put up partitions inside their house?”

Almost everyone raised their hands. Sunim spoke to the Gup.

“At this rate, it seems the people here are almost as poor as those in Jangbi Chiwog.”

The Gup replied.

“Yes, it’s similar to Jangbi Chiwog. Kella village first got a bridge connecting it in 2014, and before that, there was nothing. The road has only been here for about 10 years. And there are several households where only women live without husbands, and those houses are truly the poorest.”

Next, the agricultural environment was checked. Sunim verified if there were any places where water was being lost from the irrigation canals and if water was properly reaching the fields.

Sunim showed a video of people in Nabji Chiwog making irrigation canals. He explained the principles of JTS projects and the targets for support to the residents, and gave detailed instructions on how to build fences to keep out animals. The villagers listened attentively to every word Sunim said.

After explaining all the JTS projects, Sunim asked the residents:

“The goal of JTS is to make your lives a little more convenient. Do you think this will be helpful to you?”

“Of course.”

Finally, Sunim explained how the JTS funds were raised and urged them to use the funds, which came from donations by Korean Buddhists, economically.

After listening to Sunim’s explanation, a villager said:

“First, the most urgent need is actually the road. We’d like to repair even a part of it. If we could do that, everyone would benefit. Second, the people we talked about to Sunim today are those who are truly poor and unable to build houses. We hope they can receive support. Third, we need to make paths for people to walk on. These are the three things I really want to mention. Many people have made requests, and Sunim has said Sunim will provide support, but I have a concern. I’m worried that if all the construction materials are provided but the work doesn’t progress, the materials might go to waste. So, instead of starting many projects at once, I hope we can prioritize these three essential things. If we make good use of what Sunim has provided, our village will really benefit.”

Sunim explained that road construction is not a JTS project and once again clarified the principles of JTS projects to the residents to distinguish them from government projects.

Sunim returned the offerings made by the residents for them to eat and gave a donation to the Tshogpa for the residents to use. Sunim once again urged the Tshogpa to ensure that the donation would reach all the poor residents.

“Please make sure the donation reaches all the residents.”

Sunim examined the condition of the rice offered by the residents.

“The condition of the rice is better than I expected. It seems good enough to sell, but I’m not sure how it would taste when cooked.”

After the meeting, Sunim called the Tshogpa, Gup, and Deputy Chief and urged them to request the Sangha, who owns the land, to correct the high ratio of rice they take from the residents’ harvest.

“The monastery should take less than ordinary landowners, not more. In Bumthang, landowners initially took a 2:1 ratio, then changed to 1:1, and now it’s 1:2.”

“Yes, we know. However, this place is just continuing the old way. The villagers are kind and rural people, so they didn’t raise any issues. Also, no one from outside had ever raised this issue, so it hasn’t changed.”

“This needs to change. You should talk to the chief monk of the Trongsa Sangha about this situation.”

“I will speak to the chief monk.”

After the conversation, Sunim had lunch with the food prepared by the Kella villagers. After two hours of dialogue with the Kella residents, Sunim walked to where the car was waiting and said to the Tshogpa:

“Check the village situation thoroughly. It may be difficult for the Tshogpa, but the more effort the Tshogpa puts in, the more benefits the villagers will receive.”

“Yes, I understand.”

“I’m glad we came to Kella village today.”

Sunim retraced his steps and traveled for two hours. At 2 PM, he arrived at the Bagochen-bulingpang Chiwog in Nubee Gewog. Bagochen-bulingpang Chiwog had a separate meeting room.

“Is this the meeting room of the Chiwog?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Usually, Gewogs have meeting rooms, but this is the first time I’ve seen a meeting room in a Chiwog.”

After the welcoming ceremony, Sunim responded to the offerings from the villagers by reciting the Three Refuges in Pali and giving blessings.

Sunim began his conversation with the residents of Bagochen-bulingpang, the last stop on his survey of Trongsa District.

“It’s nice to meet you all. Is this your first time seeing a monk from a foreign country?”

“Yes.”

“I’m from Korea. It’s far to the east from here. I didn’t come to this Chiwog just to provide support. I came to see how you all live. Everyone is well-dressed, the meeting hall is nice, and it seems you’re living comfortably. I hope you continue to live well like this.

That’s why more and more people are coming to listen to my Dharma talks. Those who have been freed from their afflictions after hearing the Dharma make offerings to me. Usually, after receiving offerings, if you say, ‘Please tell us about the Buddha’s teachings,’ I’ll stop by and give a Dharma talk while passing through.

Buddhism was introduced to Korea 2000 years ago, and it has been a Buddhist country for a long time. A hundred years ago, Western culture came in, bringing modern education and development. It’s true that there has been significant economic progress. However, most of the traditional culture has been destroyed. The roads are well-developed, there are many buildings, and the amenities are good, so when foreigners visit, they feel that people are living well. But the people living there are struggling. Is this really living well?

I don’t think this is living well. Koreans have more worries than you. That’s why when I give Dharma talks, more and more people come to listen. Those who have been freed from their worries after hearing the Dharma make offerings to monks. Usually, when offerings accumulate, temples are built, but Buddha’s teachings are different. Buddha’s teachings are about relieving the suffering of sentient beings. So JTS, after consulting with Korean Buddhists, decided not to build temples but to help those in need. Instead of building temples, we dig wells for those without water, provide food for the malnourished, build schools where there are none, and create hospitals to provide medical treatment.

Bhutan is not so difficult that it needs support. Bhutan is preserving nature and maintaining its traditions well. It also maintains its Buddhist faith. This is Bhutan’s identity. If foreigners want to come to Bhutan, it’s because the natural environment is well preserved, traditions are well maintained, and you are keeping your Buddhist faith well. This is not the case in other countries. When you maintain traditions and protect nature, life becomes a bit inconvenient. For example, when protecting nature, there’s a lot of damage from wildlife when farming. In Nubee Gewog, they say tigers come and eat yaks. But because Bhutan is protecting tigers, farmers suffer losses due to tigers, but they can’t eliminate them. And wearing traditional clothes makes daily life a bit inconvenient. While preserving nature and traditions is important, human life constantly seeks convenience. So while older people live maintaining traditions, young people leave for cities or foreign countries in search of convenience. Therefore, the goal of the JTS project is to make your life cleaner and more convenient while minimizing damage to the traditions and nature you have.

However, from what I see, you people of Bagochen-bulingpang Chiwog don’t seem to have any difficulties. You are not the recipients of aid, but people who should be helping those in need in other Chiwogs along with me. The fact that so many of you have come today means that there could be more workers to participate in the JTS project.” (Laughter)

Sunim recounted the various projects that had been supported in other villages. He introduced a range of initiatives, including building houses for the homeless, repairing household facilities, constructing toilets, and creating irrigation and drinking water channels.

“When water is scarce, we need to supply it. So, the residents built water channels using pipes or cement. The goal of this project is to improve living facilities so that people can live a little more comfortably. However, what I’m saying doesn’t apply to you, does it? You all do these things with your own money.” (laughter)

The residents responded:

“Every word you say, Sunim, makes perfect sense.”

“If there’s even one person in this village who qualifies for JTS support, let’s help that person together.”

“Yes, in our village too, there’s a shortage of water, and there’s one person without a home.”

While Bagotsen-Bullingpang Chiwog was not as underdeveloped as other villages due to its proximity to the city, residents still voiced several requests, including issues with drinking water, fencing, a homeless elderly person, and the desire to rebuild old houses.

After concluding the dialogue with the residents, Sunim moved to his accommodation.

The only remaining schedule was a meeting to summarize this field trip with the team leaders of Trongsa Dzongkhag. Before getting into the car, Sunim joked with Jamyang, the Trongsa administrative officer:

“Jamyang, you must be glad it’s over now.”

“Sunim, this is just the beginning.”

“That’s right. For about three years, don’t think of it as work, but as serving the people of Trongsa and accumulating merit.”

Sunim encouraged Jamyang, the Trongsa administrative officer, and Yeshi, the central government official. After moving to his accommodation and taking a short rest, Sunim held a meeting with the team leaders of Trongsa Dzongkhag from 5 PM.

Sunim first explained in detail what JTS aims to do in Bhutan.

“My main work is Dharma talks, where I listen to people’s anguish and help resolve it. I conduct these Dharma talks with many people both in Korea and abroad. Nowadays, there are also many viewers through media like YouTube. People who receive help through these conversations make small donations to JTS. Although the individual amounts are small, so many people donate that it adds up to a significant sum. We discussed how to use this money and decided, following the Buddha’s teachings, to use it to help those in need.

To carry out this work, JTS established three mottos. First, hungry people must eat. Second, sick people must receive treatment. Third, children must learn at the right time. This work is not bound by political ideology or religion. Therefore, anyone can be a recipient of help, and anyone can participate in giving help. People from all countries and religions can be beneficiaries, and anyone who agrees with this purpose can participate, not just Buddhists. In this way, we have been active for the past 30 years, helping poor people in many countries. Where learning was needed, we built schools. In India, we built schools for untouchables, and in the Philippines, we built schools for indigenous people and those with disabilities, providing learning opportunities for those marginalized from education. This is because when government budgets are insufficient, these people are often the first to be excluded from education. In areas where water is scarce, we’ve worked on supplying water by digging hand pumps. In poor villages, we’ve conducted village development activities. We mainly focus on building houses for those without homes.

However, in the case of Bhutan, we didn’t start supporting them from the perspective of aiding a poor country. When we look around the world, Bhutan’s actual living standards are quite good compared to its national income. This is because educational opportunities are provided to all children. Although road conditions are poor, all villages are being connected by roads. Electricity is also available everywhere. In some poor countries, these benefits are not provided.

Can We Be Happy While Consuming Less?

The reason I came to Bhutan is to create a new alternative to the climate crisis. It’s to find an answer to the question, “Can we be happy while consuming less?” Currently, the world uses consumption levels as a criterion for determining whether people are living well or not. They rank countries based on GDP or GNP as a standard for living well. However, the 4th King of Bhutan said, “This is wrong. How can we say people are living well based only on material indices?” and first proposed the concept of Gross National Happiness (GNH). When this concept was first introduced 20 years ago, people didn’t pay much attention. But as the climate crisis has arrived worldwide, people have begun to turn their attention to the happiness index. Now, countries like New Zealand and Finland consider how much their citizens’ happiness will increase when the government invests in projects. This is quite different from just calculating the economic ripple effects.

In Bhutan, we’re not just making a theoretical claim that “we can be happy while consuming less,” but we’re trying to actually create a village where we live that way. To do this, we thought that a minimum standard of living should be supported for people to live happily. It’s difficult to say “you can be happy if you just set your mind to it” when there’s not enough water to drink right away. To have a minimum standard of living, you need food, clothing, and a house to live in. Electricity should be available, and road connections are necessary. And nowadays, who doesn’t use a mobile phone? These basic living conditions should be met. However, we should know when to stop pursuing better clothes, better food, better houses, and so on. After observing various countries around the world to create a model that can solve these problems, we thought Bhutan was the most suitable.

Many people tell me to conduct such experiments in Korea. However, it’s not easy to do in a country with a consumption level like Korea’s. There are many Jungto Society members in Korea who support my vision. But when trying to create a model for an entire region, while some agree, many others don’t. Reducing consumption levels is actually very difficult. Once people develop a habit of consuming, it becomes hard to stop. If you tell someone who owns a car to ‘stop using it’ or someone who keeps their refrigerator full of food to ‘stop using the refrigerator,’ you’ll face strong resistance.

So we looked for a region with a slightly lower income level and well-preserved natural environment. Also, to be happy with less consumption, one needs to practice mind training. Bhutan met these conditions. Bhutan has a good natural environment and, while not heavily developed, has achieved some basic development. It has preserved its traditional culture and religiously, it’s a Buddhist country. That’s why we decided to create a model region for humanity’s future in Bhutan. However, seeing how Thimphu is changing, I sometimes wonder if coming to Bhutan was the right decision. Thimphu is developing rapidly. I discussed with the King of Bhutan and decided to start with the poorest region as a model. When I consulted with the Cabinet Secretary, Zhemgang was identified as the most challenging area, which is why we came here.

To Prevent Seeking Happiness Only Through Consumption

JTS aims to support people living below the basic standard of living. We don’t support efforts to consume beyond that level. However, we can’t forcibly prevent people from consuming more. That’s an individual choice. But residents need to practice mind training to avoid seeking happiness only through consumption. Monks should take on this role, but Bhutanese monks seem to have difficulty teaching mind training. Instead of teaching people to live frugally and seek happiness through mind training, they focus on praying for people’s good fortune. They don’t seem prepared to consider the future in the era of climate crisis or to aim for a new society, and they appear to lack awareness of social issues. As an alternative to this problem, I’m considering female practitioners, bhikkhunis. Of course, the social status of bhikkhunis is still low, so considerable education is needed. While monks may offer blessings because people need them, they should primarily transmit Buddha’s teachings. They need to be able to teach the Dhamma. To do this, they not only need to know Buddha’s teachings in detail but also have at least high school-level knowledge of science, math, social studies, and history. However, bhikkhuni nuns haven’t received that level of education yet.

The Buddha’s teachings should not be just an old story but should serve as effective medicine to solve the problems of people today. When Westerners, tired of material civilization, come here, we should be able to become their spiritual teachers. Currently, tourists come to see Bhutan’s natural scenery and traditional culture, but this alone has limitations. In the future, we should establish meditation centers here so that foreigners can stay, reduce consumption, meditate, and learn the Buddha’s teachings to change their way of life. In this way, we should play the role of teachers for people around the world.

For this to happen, the most outstanding people from schools should become monks to fulfill this role. The Buddha was able to become a teacher to all beings because he gave up the opportunity to become a king and became a practitioner instead. That’s why we are now discussing with the Bhutanese Bhikkhuni Foundation about how to educate bhikkhunis. For this goal to succeed, properly educated bhikkhunis should be dispatched to each chiwog, one per chiwog. They should reside in each temple and take care of the residents. So, people like you should all become monastics.” (Laughter)

Sunim then shared his impressions after surveying the entire Trongsa Dzongkhag over the past seven days.

“Overall, after touring Trongsa Dzongkhag, the living standards of the residents seem to be definitely better than in Zhemgang. Of course, there were three or four villages that were as poor as Zhemgang. Jangbi Chiwog, Gela Chiwog, Baling Chiwog, and Samcholing Chiwog definitely looked impoverished. The rest mainly had water supply issues. Requests for fencing the fields were common everywhere. In the more well-off neighborhoods, everyone asked for road paving, which falls under government projects.

There were occasional requests to help people with disabilities and those in extreme poverty, but we can’t assist them individually and must follow the Bhutanese government’s policies. So, we should investigate these cases and request the government to address them. If the government says they can’t provide support, we’ll discuss how to handle this issue again. There were also some homeless people without land. We should gather all these cases and request land for housing from the royal family.

Issues like cataract surgery, hearing aids, or dentures for those without teeth are not disabilities but are necessary for people. Since there are many elderly people in rural areas, a survey needs to be done first to address this problem. We can’t bring doctors at our discretion; we must report to the government and get their permission. Then the government will decide which doctors to dispatch. If the government says they don’t have doctors to send, I will invite doctors from abroad. Once a doctor examines and decides, ‘This person needs a hearing aid,’ or ‘This person needs cataract surgery,’ we need to provide the actual treatment. So, first, have the health care representative conduct a survey.

Next are the schools. If the classroom floor is damaged, it needs to be repaired. All toilets need to be remodeled. If there are problems with dormitories, they need to be fixed. The school in Yebilaptsa had good classrooms, but the toilets were in terrible condition. So the Department of Education should conduct a comprehensive survey and make a collective request. When we ask at schools, they mostly request laptops for educational equipment. For example, in a class of 10 students, they only have 5 laptops, so the remaining 5 students can’t practice. This doesn’t mean giving a laptop to every student, but rather having enough for all students to learn simultaneously in the computer lab. So we’re trying to get many used laptops from Korea. Some better-off schools are asking for smart TVs, but let’s put that off for now. We’ll prioritize providing laptops first.”

Sunim spoke in detail about JTS’s business principles for sustainable development.

JTS’s Business Principles for Sustainable Development

“First, it must be something that the residents really need. Second, the technology used in this project should be local technology. This is because if it’s external technology, it can’t be repaired when it breaks down later. It should be something that residents can do themselves, not something that someone else comes to do. Third, the materials used should preferably be produced within Bhutan. Fourth, many people should participate. Fifth, it should benefit many people. Sixth, people should be able to do the work joyfully, not suffering in the process. Seventh, it should be carried out in a way that doesn’t harm the environment. Eighth, it should cost little money. If it costs less, we can spread it more widely. If it costs a lot, we can only do a little. Even if you produce a lot of corn in a field with metal fencing, you can’t recover the cost of the metal fence. The same goes for projects that connect water channels with pipes over long distances to irrigate rice fields. You don’t make much profit from growing rice and harvesting it, so connecting pipes for 3 kilometers to irrigate the fields is wasteful. There may be no one to farm in rural areas 10 years from now. So we shouldn’t make too many investments blindly. We need to research methods that can maximize efficiency through minimal investment.

However, the government can’t just consider economic efficiency. They need to accommodate residents’ opinions in preparation for elections. So government projects can include things like installing metal fences or laying long water channels. But these aren’t suitable for JTS projects. However, it’s possible to repair existing water channels rather than creating new ones. Also, if the water channels are made of soil and lose a lot of water, we can support cement. For cemented water channels that frequently collapse due to steep slopes, we can support pipes. In other words, water channels passing through cliffs should be made with pipes.

Would You Invest in This Project If It Were Your Own Money?

The most important principle is to consider, “Would I invest in this project if it were my own money?” Clean drinking water requires pipes, but irrigation channels for fields can be open. While cement is produced in Bhutan due to limestone deposits in the south, pipes and steel must be imported. I suggested using wooden posts with wire fencing for boundaries. People are reluctant to use wooden posts as they rot in three years. However, if we use cuttings that can take root, they will grow into living fences even after the original posts decay. The Bhutanese government currently spends an enormous budget on steel fencing. If the crops produced within these steel fences were extremely valuable, it might be justifiable. But it’s not cost-effective for corn, which isn’t a high-value crop. Politicians may have to accommodate such demands, but as administrative officials, you must always consider economic efficiency.

My initial plan was to have the government implement this project. However, when I surveyed the site, I found that residents were simply demanding government projects unconditionally. So I changed the plan from a government project to a JTS project. When they heard that a monk was helping, their attitude changed: “Even our relatives don’t help us, but this monk is helping. We should also participate!” Many people doubted whether the residents would cooperate with this project. When I first visited the village, the residents only made demands. It took a long time to convey that this project is a collaboration between JTS and the residents. I’ve already visited Bhutan 12 times. As a result, the Tshogpas have begun to understand a little. Some residents are also starting to understand. Nevertheless, when they talk to me, they say they understand JTS’s project principles. But as soon as we finish talking, they go back to saying, “Please do it for us!” (Laughs)

The villagers must be struggling to manage both their farming work and the JTS project. Moreover, most people in rural areas are elderly. Since they’ve become accustomed to receiving government support over the past decade, we need to keep reminding them that they should continue to do the work themselves. Sometimes I feel sorry. It’s not easy to refuse when they ask for help. Some villagers might think, ‘They said they came to help, but what are they really doing?’ However, JTS’s principles are now starting to take root.”

Sunim then showed a video of last year’s pilot projects, including irrigation construction, road paving, and building houses for the poor.

Finally, Sunim emphasized once again why this JTS project is important.

“If this project succeeds in Zhemgang and Trongsa, we plan to expand it to the entire Bhutan in 5 years. This will require a substantial budget. When we demonstrate success, many people will be more inclined to donate. We’re not accepting donations now because we’re unsure if this project will succeed or fail. If we were to accept donations first and the project fails, we’d be indebted to our supporters. There are many people in this world who ask for donations, saying they have plans to do something. This not only fails to raise funds but can also make one a liar. However, if we first show successful results, people will realize, ‘Wow, even a small amount of money can help so many people!’ This naturally encourages them to participate in donating. The success of this project is necessary not only for the current residents here but also for its future expansion throughout Bhutan. Let’s start with this perspective in mind.”

After the explanation, participants shared their thoughts.

“Yes, Sunim. Now I understand what you’re trying to accomplish,” one person remarked.

After concluding the meeting, everyone had dinner together. Sunim then presented prayer beads from Bodhgaya and seaweed from Korea as gifts to the Trongsa district officials.

Sunim also encouraged the Trongsa administrative officer, driver, and interpreters who had accompanied the group for ten days, and took commemorative photos with them.

As the group was heading back to their accommodation after completing all scheduled activities, the owner of the Trongsa hotel approached Sunim seeking a blessing.

Sunim blessed the Trongsa hotel owner and presented him with a set of prayer beads.

“Thank you. I’ve rested well during my stay.”

Finally, the Trongsa survey itinerary has been completed. The plan is to depart for Thimphu early tomorrow morning.