Nov 17, 2024 Jungto Dharma School Q&A, National Dharma Teachers’ Training

Good morning. A new day has dawned at the Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center.

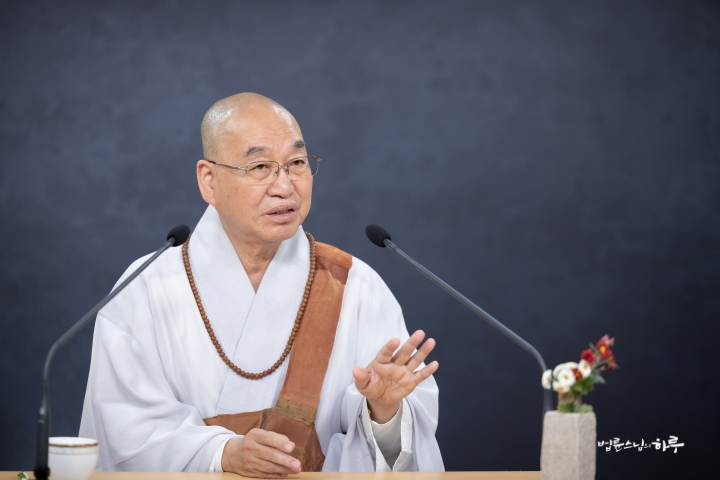

After completing early morning practice and meditation, Sunim began the day with an online Dharma Q&A session with Jungto Dharma School students at 8 AM. The Jungto Dharma School is an English-language course equivalent to the Jungto Buddhism Course. Eleven students from the Western and Eastern United States and Korea are attending the class.

After hearing feedback from a few participants, Sunim explained in detail what perspective students should have when studying at the Jungto Dharma School and why they should study the life of the Buddha. The students have completed Course 1, Original Buddhism, and are now studying Course 2, The Life of the Buddha. Today’s session is dedicated to addressing questions that arose while studying the Buddha’s life. Two students raised their hands on Zoom and asked Sunim questions.

What Is the Goal of Becoming a Monk, as It Seems Unproductive?

“I can understand why you might have such questions. The Buddha did not independently create the concept of becoming a monk. He participated in the already existing social trend of renunciation. At the time of the Buddha’s birth, traditional Indian society was known as the Brahmin civilization or Aryan civilization. The Brahmin priestly class formed the highest leadership in that society. In most societies, including China, religious leaders and political leaders initially coexisted as one, but as they separated, political leaders usually took precedence. In India, however, it was the opposite – religious leaders took precedence over political leaders. The first caste was the priestly Brahmin class, the second was the political leader class called Kshatriya, and the third was the economically powerful Vaishya class. The caste system in Indian society was created when the Aryan people conquered the indigenous Dravidian people and organized them into the fourth caste, the slave class called Sudra.

During the era when the Aryans were conquering the Dravidians, it was believed that the power of the Brahmin gods brought victory. However, in the era when the Dravidians had been fully conquered, the competition was between countries that all believed in the same Brahmin gods. Therefore, what gave the competitive edge was not the power of the gods but economic and military strength. As a result, the influence of the Kshatriya class grew, eventually surpassing that of the Brahmins. While countries were politically independent and competitive, economically, trade transcended national boundaries, leading to the formation of great wealth and an elevated status for the Vaishya class of wealthy merchants. If we compare it to today’s society, you can see it as a shift where political influence became greater than religious influence, and the power of multinational corporate leaders became comparable to that of political leaders.

As a result, the traditional class hierarchy began to collapse, and new thinkers emerged to explain this changed society. Traditional mainstream thinkers, the Brahmins, held authority based on their birth status. However, the emerging thinkers could not claim such authority as they were not of Brahmin origin. Therefore, they sought to gain authority through their own choices, supported by the masses. While there was a custom in traditional society for people to leave home at a certain age, these new thinkers chose to leave their families and homes of their own accord. They began to beg for alms, live very frugally, and expound their own ideas about the world. However, because they were not Brahmins, their opinions were not initially accepted by society. As society gradually changed, their ideas began to gain acceptance.

Although all the emerging thinkers opposed and rejected Brahmanism, their philosophical explanations of “how the world is” were so diverse that they did not share a common perspective. Nevertheless, they did have one thing in common: they left home, shaved their heads, wore tattered clothes, begged for food, and lived very simply. This group was collectively called “Samana.” Buddha joined this group, which is why he also left home, shaved his head, and lived as a mendicant. In other words, before renouncing the world, Buddha held the beliefs and ideas of mainstream Brahmanism, but after leaving home, he became immersed in the various philosophies of the Samana. However, when Buddha attained enlightenment, he transcended the extremes of both sides and found a new path. This is why his enlightenment is described as the “Middle Way.” However, from the social perspective, he belonged to the Samana group because he was not a Brahmin. Thus, his disciples were all classified within the Samana group, and they renounced the world following this tradition.

There were only two instances when the Buddha directly told people to become monks. The first was when he encouraged his son to become a monk. The second was when he persuaded his younger brother that it would be good to become a monk. Other than these instances, the Buddha rarely told people to become monks. When people requested, “I want to become a monk. Please accept me into the Sangha,” he welcomed them, saying, “Come, bhikkhu!”

Those who heard and understood the Buddha’s teachings could choose between two paths. One was the path of a lay practitioner, pursuing liberation while remaining in the secular world. The other was the path of a monastic practitioner, leaving home to pursue liberation. For those who chose to practice while staying at home, he gave five specific precepts. First, do not kill living beings carelessly. Second, do not take what is not given. Third, do not engage in sexual misconduct. Fourth, do not use abusive language or lie. Fifth, do not hold wrong views. The wrong views here refer to seeking pleasure through intoxication and excitement. It means understanding liberation as pleasure and considering pleasure as happiness. This later became translated as “do not drink alcohol to the level of intoxication.” The Buddha warned that living in the world carries a high risk of breaking these precepts, so practitioners should be cautious of these at the very least. However, for those who had become monks, there was initially no need for precepts as they were unlikely to engage in such behaviors. Later, as some people became monks perfunctorily without fully renouncing worldly attachments, losing the perspectives of the practice, precepts were established for monastic practitioners as well.

So, as the questioner mentioned, you don’t need to worry about ‘What would happen if everyone in the world became a monk?’ This is because the Buddha never told people to become monks. He simply said that if they wished, they could choose to be either a monk or a layperson as they desired. He only provided guidelines such as, ‘If you practice as a layperson, you should follow these principles at least,’ or ‘If you practice as a monk, you should observe these rules.’ He never mandated which path one should take. Even regarding the prevalent gender and caste discrimination of that time, he did not tolerate it within the Sangha community of monks.

Jungto Society follows this model of the Sangha. While individuals are free to choose their profession and receive a salary for their livelihood, once they enter the community, we don’t have a system of giving and receiving salaries. Typically, organizations need some economic foundation to operate, but the method of becoming a monk in Buddha’s time could spread without any economic basis. This was because they lived by the principle of not using resources that others could use, and in return for not working, they didn’t use any products produced by human labor. They ate leftover food given by others and wore discarded clothes that no one else would wear. In India at that time, no matter how poor, people wouldn’t use the cloth that had covered a corpse. They believed wearing such cloth would make their body dirty and impure. When becoming a monk, they would cover their body with cloth that had been used to cover corpses. They slept under trees or in caves. If there was an abandoned house where no one lived, they were allowed to sleep under its eaves. As the questioner mentioned, they didn’t use anything produced by people that others could use. Therefore, no matter how many monk practitioners there were, it didn’t burden the people of the world, and no economic effort was needed to maintain the foundation of the Sangha.

However, 500 years after Buddha’s parinirvana, the lifestyle of practitioners began to change. They built temples as places to live, wore robes made from fine cloth received as donations rather than discarded rags, and ate good food that was offered to them. This lifestyle was made possible largely due to donations from kings and wealthy people of the time. As a result, they transformed into a class that only consumed without producing, similar to how it is now. Therefore, I believe it’s reasonable to question modern monastic practitioners: “If you use what others have produced, shouldn’t you also participate in some form of productive activity?”

However, we should understand that when Buddha said “do not participate in productive activities,” he meant “do not pursue profit.” Whether farming or doing any other labor, the intention was not to receive compensation for that work. In other words, the most important aspect is not pursuing profit. That’s why in Jungto Society, we have a system where no matter what activities are performed, no compensation is received.

“That was very clear. Thank you for the explanation. I think the main thing was that there was a clash between how I see the current monks and the monks that are described in the textbook. I think you’ve resolved that issue.”

After answering the following questions, the live broadcast ended at 9:30 AM.

Shortly after, at 10 AM, Sunim attended the National Dharma Teachers’ Training. This is the fourth National Dharma Teachers’ Training since the start of the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice. Today, the focus was on discussing the role of Dharma teachers in preparation for the 100-day special practice and Sunim’s 100-day Dharma talks planned for the first half of next year.

Before starting the training, Sunim gave an opening Dharma talk. He discussed how Jungto Society, which has entered a stagnant phase, could find a new breakthrough and what the role of Dharma teachers would be in this process.

“The original plan was to have a one-year preparation period after the 1st 10,000-Day Practice to start anew before beginning the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice. I even thought we might need about three years to prepare for the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice. However, when viewed in the context of a long history, such preparation periods would not fit neatly into 30 or 60-year units, so we started the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice immediately after the 1st one. As a result, although we set various goals, we began the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice without being fully prepared to handle them. So, even though we call it the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice, it seems we are progressing as an extension of the 1st 10,000-Day Practice.

Reasons Why Activities Are Not Adapting Well to Online Methods

The major change in the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice can be said to be the shift to online. In fact, we had already begun the transition to online at the end of the 1st 10,000-Day Practice due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, from a broader historical perspective, it can be evaluated that the 1st 10,000-Day Practice was conducted offline, while the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice is being conducted online. Although we have made this transition to online, the current leadership of Jungto Society consists mostly of people who have experienced and been trained offline. Since the younger generation familiar with online methods cannot immediately become leaders, although we have transitioned to online, we cannot say that our activities are fully adapted to the online environment yet. I think this is one of the factors contributing to the current stagnation that Jungto Society is facing.

Of course, when we started the 2nd 10,000-Day Practice, we formed an ‘Online Activities Committee’ to strengthen our online methods, but there hasn’t been any significant progress so far. This is not because of issues with the committee members, but because none of us have experience with online methods. While our society is transitioning to online, Jungto Society lacks the technological accumulation to lead this transition ahead of society.

So, I think that if there’s anything more we can contribute to invigorating Jungto Society with our current experience, it might be to revitalize our offline activities. And as society moved online but is now returning to offline as the COVID-19 pandemic ends, we’re in a situation where offline activities are once again playing an important role, though not quite returning to pre-pandemic conditions. While the overall direction is still moving towards online, offline activities have become important again compared to during the pandemic. Therefore, since there are limitations to only conducting online activities, we came up with plans to revitalize the Jungto Social and Cultural Center as a way to reinforce our offline activities.

Last October, when all the Jungto Society executives gathered at the training center to form a task force, there were some concerns and evaluations that this plan alone would not be effective enough. The original plan was for Sunim, as the guiding Dharma teacher, not to participate at all. Sunim had planned to start pioneering projects from the second 10,000-Day Practice onwards. He thought it would be good to invest his capabilities in activities such as revitalizing international branches for global Dharma propagation, building self-sustaining systems for each country for JTS’s long-term development, securing stable food sources in an era of environmental crisis, and establishing future bases in local areas considering the retirement of long-term activists. Therefore, Sunim had decided to opt out of the 100-day special practice. However, many concerns were raised that if Sunim were to be absent, the plan might lack momentum. As a result, the plan is currently being adjusted for Sunim to give Dharma talks during the 100-day period. If it’s decided that Sunim will fully participate, all planned activities for next year, including overseas lecture tours, overseas JTS projects, and domestic lecture tours, will have to be comprehensively readjusted.

The Role of Dharma Teachers in Bridging the Online and Offline Worlds

The online approach offers many advantages. With online technology, Dharma teachers can provide personalized and attentive guidance to individuals in their practice. However, it is challenging to foster mutual personal connections and meaningful interactions online. To cultivate personal influence, expanding offline meetings is essential. That said, offline gatherings often require Dharma teachers to address large groups, resulting in them speaking extensively. Regardless of how it is framed, this inevitably tends to shift toward a lecture-style approach, which poses its own challenges. ‘How can we find harmony in this situation?’ This is a challenge that the Dharma teacher community must continue to develop and pioneer moving forward. Dharma teachers should focus more on listening rather than speaking, but in offline settings, they often end up taking on a speaking role. Therefore, it is essential for all of you to explore and discover a balanced approach that leans neither too far in one direction nor the other, based on your own experiences.

“This experience of navigating between online and offline platforms is historically unprecedented for us. Even great masters like Wonhyo, Seosan, and Yongseong never encountered such a situation. Therefore, simply interpreting the sayings of ancient patriarchs won’t solve this issue. It’s our responsibility to develop creative methods to address this challenge. We must abandon the mindset of following someone else’s teachings or waiting for others to solve these difficulties for us. We need to pioneer our own path by trying various approaches. Additionally, we should share these experiences among our roughly 100 Dharma teachers to explore and develop better methods. I hope you’ll actively participate in today’s discussion with this perspective in mind.” After the opening Dharma talk, the Weekly Dharma Assembly, Buddhism Course, and Sutra Course groups presented their analyses of the issues and proposed improvements.

After listening attentively to the presentation for an hour, Sunim had lunch.

After finishing the meal, group discussions were held in the afternoon. 11 groups discussed various topics such as the challenges and alternatives faced by volunteers when they transferred to other divisions, the role of branch Dharma teachers, strategies for personnel assessment and management, and the retirement age of leading members. After the discussions, everyone gathered back in the video conference room.

From 3:30 PM, each group presented their discussion results. Sunim listened carefully to the presentations from the Dharma teachers and took notes on important points.

After the presentations, Sunim summarized the discussions and held a Q&A session. The Dharma teachers asked questions about their roles, citing various examples from branches and sub-branches. After the Q&A, Sunim gave some final words of advice.

“Recently, some Dharma teachers have requested sick leave. Among the community Dharma teachers, some have requested leave due to cancer or traffic accidents, and several Dharma teachers from the Lay Member Group are unable to attend meetings due to illness. It would be nice if you could call them occasionally and offer words of comfort despite your busy schedules. It would be good to visit them once in a while to show that they are not alone, thanks to their involvement in Jungto Society activities. The best thing would be for me to show concern and visit them myself, but my current situation doesn’t allow for that. I need to remain detached to focus on my work. So, I’m asking you to show concern and take care of them if possible.”

The national Dharma teachers’ training concluded with the Four Great Vows just after 5 PM. When Sunim left the broadcasting room, the sun was setting.

Sunim departed from Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center and headed to Daegu Airport. After an hour’s drive, he arrived at Daegu Airport.

Grabbing a quick bite with some bread at the airport, Sunim boarded a flight at 7:55 PM from Daegu Airport. After an hour-long flight, he landed at Jeju Airport at 8:55 PM.

Upon leaving the airport, Sunim headed to his accommodation. After renting a car, he arrived at the accommodation at 11 PM.

After having a late dinner at the accommodation, Sunim retired for the night.

Tomorrow, the tenth Dharma Q&A session of “Happy Dialogue” is scheduled to take place at the Halla Art Hall in Jeju City.