Nov 5, 2024 – Farm Work, 5th Day of Women’s INEB Visit

Hello. Today marks the fifth day since the Women’s INEB (International Network of Engaged Buddhists) delegation began their visit to Jungto Society.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim began the day by having Barugongyang (formal Buddhist monastic meal) with the Women’s INEB delegation.

After setting up the food, the Barugongyang began with the resonant sound of the Dubuk community members reciting the Short Heart Sutra.

“May I refrain from all evil, cultivate all good, and purify my mind. May all sentient beings attain the supreme way together.”

After reciting the Short Heart Sutra and placing rice, soup, and side dishes in their bowls, everyone ate quietly.

After the meal, the morning assembly was held. After sharing any violations of precepts or announcements for the community, We had a time to introduce the women’s INEB delegation to the public Representing the Women’s INEB delegation, Ven. Jigmet from Ladakh shared her impressions of spending a day at the Dubuk Retreat Center.

“I have visited many organizations, but I have never seen a founder dedicating his time so completely to be with us. Even though we are guests, Venerable Pomnyun Sunim has met with us every day and given us a lot of his time. I am truly grateful.

In India, I had only tried Korean foods famous there like ramyeon, gimbap, and kimchi. But during this visit to Jungto Society, I realized, ‘Ah, there are other foods in Korea besides ramyeon, gimbap, and kimchi.’ It was great to experience what Korea is really like. I especially thank the kitchen staff who prepared the meals for us.”

Sunim then explained the meaning of Barugongyang to the Women’s INEB participants.

“Baru originally means a bowl that holds an appropriate amount. Practitioners should consume the minimum amount of food necessary to maintain their bodies. In other words, food should be eaten as medicine to sustain the body. Nowadays, people prepare food and offer the best to monks first, but in Buddha’s time, monks obtained food through alms. Just as leftover food is given to beggars, monks also ate food that people were about to discard. The same was true for clothes. When one became a monk, they wore clothes that people had discarded. However, even discarded clothes were needed by poor people. So monks wore clothes that had been used to cover corpses. Even the poorest people wouldn’t use clothes that had covered corpses. The kasaya (Buddhist robe) worn by monks today inherits this spirit. And they slept under trees. However, it was permitted to sleep under the eaves of abandoned houses where no one lived.

Barugongyang: Inheriting the Spirit of Alms-Round

Practitioners were not supposed to engage in any labor, but in return, they were not to use anything produced by the labor of others. However, today, many monks use products made by the labor of ordinary people. Therefore, it is wrong for monks to avoid doing any work. If they use things made by others’ labor, they should also work themselves. The saying “practitioners should not work” means they should not pursue any profit. Thus, if a practitioner receives compensation for any labor, it goes against the principles of practice.

In India, beggars were respected as practitioners. Even now in India, the act of begging, called “Baksheesh,” is not viewed negatively. However, in China, begging is seen very negatively. When Buddhism was introduced to China, monks followed the Indian tradition of alms-round, but this was viewed negatively in China. As a result, it became difficult to practice alms-round, and eventually, monks began to prepare meals in the temple. Preparing meals in the temple is similar to secular life. So, while they cooked the food, they would then practice alms-round with the prepared food. This is called Barugongyang. Barugongyang can be said to inherit the spirit of alms-round from Buddha’s time. It involves sharing the food prepared in the temple as if practicing alms-round.

Even in Buddha’s time, after receiving food through alms-round, they didn’t eat just anywhere. They would go down to the village from their practice place to receive food, then return to their practice place to eat. They mainly ate what they had received, but if someone was sick and unable to go for alms-round, they would share the food. In this way, Barugongyang pursues the spirit of sharing equally.

The sutra recited during Barugongyang (formal Buddhist monastic meal) is called Soshimgyeong. The main content of Soshimgyeong includes contemplating the four main pilgrimage sites of the Buddha, taking refuge in the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha), and vowing to cultivate the three trainings of precepts, concentration, and wisdom. It also involves reflecting on the merits of all those who have worked hard to bring this food to us. We sincerely examine whether we are worthy of eating this food. The purpose of eating this food is not to satisfy hunger, but to attain enlightenment, that is, to practice.

Then, while thinking of those who are hungrier than ourselves, we perform a ritual of sharing even a single grain of rice with them. We recite a mantra, wishing that a single grain of rice may become a bowl, and a hundred bowls, saying, “May all hungry people be satisfied.” This is making a vow. Also, the act of eating itself becomes a sacrifice of other lives for ourselves. For example, even when drinking a drop of water, there are numerous microorganisms in it. So, we don’t eat carelessly, but recites a prayer for them before eating. Finally, we make a vow to eat this food to attain Nirvana, and then begins to eat.

The Fading Tradition of Barugongyang

Even as everything becomes modernized, we must preserve good traditions like Barugongyang (formal Buddhist monastic meal). Unfortunately, this tradition is gradually disappearing in Korea. Instead, it has become trendy in temples to prepare delicious and abundant vegetarian dishes under the name of temple cuisine. This high-end food culture can be seen as contradicting the spirit of Barugongyang.

Jungto Society has also launched a civic movement called the ‘Empty Bowl Campaign’ to eliminate food waste. It is said that the cost of processing food waste in Korea is enough to provide food for the starving North Korean people and still have some left over. Despite being the same ethnic group, one side is starving to death while the other is wasting enormous amounts of food. This is something we really need to reflect on deeply as members of humanity.

Sunim concluded his explanation by expressing his hope that the female INEB participants would have a good experience during their stay at the Dubuk Retreat Center.

After finishing Barugongyang, everyone headed to the fields for communal farming. The bhikkhunis also changed into work clothes and set off for the fields.

In front of the field, the tasks were first divided.

“Continuing from yesterday, today we will be planting onion seedlings. We’ll divide the roles into three: those who make holes in the ground, those who put the onion seedlings into the holes, and those who cover the seedlings with soil. Is there anyone who would like to make holes in the ground?”

After dividing roles and reciting the Words to Remember “Everything has its proper place” three times, the communal work began at 7:50 AM.

However, it was announced that the work should end by 8:20 AM. The schedule included visiting Bulguksa Temple after finishing the work, but they needed to return before noon to have lunch at Dubuk Retreat Center to accommodate the bhikkhuni who doesn’t have her meal in the afternoon. Sunim asked the bhikkhuni who doesn’t eat in the afternoon:

“Even so, the work time seems too short. Is it okay if we start eating before noon? Or do we need to finish eating by noon?”

“When moving as a group, it’s fine even if it’s past noon.”

“Then, let’s work until 8:40 AM.”

“Sounds good.”

Sunim and the participants focused on their assigned tasks while occasionally engaging in conversation.

After 50 minutes of work, a clear bell sound was heard. It was time for pause and reflection. Everyone stopped what they were doing and focused on their breath.

At 8:40 AM, it was time to reluctantly end the work.

Before taking off their boots at the farm storage, they took a commemorative photo, smiling brightly and saying “Kimchi!”

Inside the farm storage, they shared their thoughts from the day’s work. Due to time constraints, they kept it brief. Sunim started the sharing:

“I’ll go first. I was happy to be able to work together today. Towards the end, I felt a bit rushed trying to plant all the remaining seedlings.”

The female INEB participants also shared their thoughts one by one, concisely.

“It was really enjoyable. I was especially excited to be able to work early in the morning.”

“My mind was busy.”

“I felt particularly grateful to be able to work alongside Sunim.”

“While planting onions with short roots, I hoped these small lives would grow well.”

“It was a great honor to see the highest Sunim working directly for the first time.”

“The wind in the field was fresh. My hands were cold, but my heart was warm.”

“Before we started, I hoped we could plant all the onions, but I’m disappointed that the work time was so short.”

After hearing the participants’ reflections, Sunim added one more comment:

“I’m not a high Sunim, I’m just a farmer.” (laughter)

After sharing, the female INEB participants departed for Bulguksa Temple. Sunim rushed back to the field to finish planting the remaining seedlings. Upon closer inspection, there were gaps here and there where seedlings were missing.

“The participants missed a few spots in between. Some just placed the seedlings on top without planting them.” (laughter)

Sunim carefully planted seedlings in every space left empty by the INEB participants. Soon, the “Tuesday Farmers” volunteers who come regularly every Tuesday arrived. They also began planting seedlings in the remaining ridges.

Sunim finished one ridge and stood up.

“I have other matters to attend to, so I’ll be leaving now. Thank you.”

Sunim continued working in the vegetable garden until noon. He sweated a lot harvesting wild greens and trimming overgrown tree branches.

At noon, the female INEB participants returned to Dubuk Retreat Center after completing their tour of Bulguksa Temple, and Sunim also finished his farm work and returned to the retreat center.

At Dubuk Retreat Center, volunteers had prepared lunch with great care.

Sunim expressed his gratitude to the volunteers and took a commemorative photo with them.

“I will eat with gratitude.”

There were 11 volunteers who prepared the meal and 11 female INEB participants. Sunim offered words of encouragement in the Gyeongsang-do dialect.

“You prepared the meal one-to-one. Is it because you’re not skilled in cooking that you gathered so many people to prepare?” (laughter)

After the volunteers introduced the dishes, everyone ate together.

After the meal, from 1:30 PM, Sunim had a discussion session with the female INEB participants. First, he provided additional explanations about Jungto Society’s operational methods that he had described so far. He explained in detail how ordinary citizens come to join Jungto Society and what systems are in place to operate Jungto Society on a volunteer basis. Then he took questions about any remaining points of curiosity.

For two hours, various questions poured in. One person asked for Sunim’s advice on how to restore their relationship with a fellow monk who had been speaking ill of them behind their back.

How Should We Deal with People Who Praise Us in Front but Speak Ill Behind Our Backs?

“Why do you think you must restore that relationship? You could part ways.”

“Should I just avoid meeting her?”

“Why are you avoiding that person?”

“Because we live together.”

“These days, even married couples with children separate. What’s the problem with parting ways with that person? Is that person also a monk?”

“Yes.”

“How did the monk you live with betray you?”

“I heard that while she praises me and says nice things to my face, she speaks very badly about me behind my back.”

“I think that’s a good thing. Because it’s better to speak ill behind your back than to your face. For example, if I’m giving this Dharma Q&A now, and after hearing my answer, you say, ‘Sunim, how can you say such things?’ right to my face, how would that be?

Is it better to say whatever you want directly? Or is it better to sit among yourselves after this session and say, ‘That monk’s words were a bit strange just now’? I think I would be very embarrassed if someone cursed me to my face.”

“But if that person had spoken to me directly, I could have reflected on myself.”

“Reflecting on yourself is something you can do whether you hear it directly or indirectly. It’s true that the person has some discomfort towards you. But she speaks behind your back because she feels a bit sorry to say it to your face. This behavior comes from a mind that respects you to some extent. The person with the uncomfortable feelings is that person. You can’t do anything about her bad feeling.

‘She respects me to some degree, so she talks behind my back instead of to my face!’

I think you can take it this way. There’s an old saying, ‘People curse even the king when he’s not around.’ In the old days, no one was allowed to complain about the king, who had absolute power. However, even if it’s the king, anyone can complain when he’s not present. You’re neither a Buddha nor a king, right? Were there people who criticized the Buddha or not?”

“There were.”

“Are you greater than the Buddha?”

“No.”

“There can be people who criticize me. However, it’s a bit better to criticize behind my back than to my face. Of course, it would be even better if they didn’t criticize behind my back either.”

“But what if someone hears that person speaking ill of me? What if they believe it and misunderstand me?”

“That could happen. But it might not. It’s up to the person who hears it to decide. If person B believes what person A says negatively about you, it’s not because A spoke ill of you, but because B also lacks trust in you. And whatever they choose to believe is their personal freedom, so there’s nothing I can do about it. The problem arises because I heard someone speaking ill of me, but there could be many such instances that I haven’t heard. If you hear someone speaking badly of you, reflect on yourself to see if there’s anything you need to improve. And if what that person says isn’t true, just let it go.

People are wise in their own way. They might believe others’ words once or twice, but after prolonged experience, they realize, ‘Ah, that person tends to exaggerate!’ Think about it yourself. Do you believe 100% of what others say? Or do you think it could be true or not? There’s no need to worry that others might misunderstand you based on what that person says. And if necessary, you can explain yourself. I don’t see it as a big problem. Of course, it’s not ideal to have people speaking ill of you, but the world doesn’t always go the way we want. Gossip is a common part of our lives. Experiencing this now will build your immunity, making it better for you later. You might even be able to smile like the Buddha when someone insults you to your face.

One day, while the Buddha was out for alms, he was severely insulted by a person. The Buddha simply smiled. This provoked the person further, who confronted the Buddha for smiling. The Buddha calmly asked him:

‘Do you have guests visit your home?’

‘Yes.’

‘And do these guests sometimes bring gifts?’

‘Of course.’

‘What happens to the gift if you don’t accept it?’

‘The guest takes it back.’

The man still didn’t understand the Buddha’s point and questioned why he was suddenly talking about gifts. The Buddha then replied:

‘You’ve just offered me the gift of insults, but if I smile and don’t accept it, who does the insult belong to?’

At that moment, the man understood. Do you understand what this means?”

“Yes, I will now maintain a relationship where I only speak to that person officially when necessary, without any personal conversations.”

“If you hate that person, you’re preventing yourself from meeting one person in this world. If you hate everyone in this world, you’ll end up alone. For true freedom, you shouldn’t mind anyone. You don’t need to try to be friendly or improve the relationship, but you should reach a level where you don’t care what that person says. There’s no need to hate or deliberately avoid them. Just greet them when you meet, and have casual conversations. If you need to gain something from that person, you might need to get closer, but if not, it doesn’t matter.”

“Thank you. I understand well.”

The bhikkhuni who asked the question expressed her gratitude to Sunim with a bright smile.

The questions continued.

Jungto Society conducts an enlightenment experience program called ‘the Awakening Retreat’. I’d like to understand more clearly what enlightenment is.

When conducting meditation retreats, many people drop out midway because it’s difficult. How should we guide people who seek comfort and relaxation to meditation?

Are there plans to conduct the Awakening Retreat program in English?

Many of the students I teach complain that living an ordinary life is too difficult. How should I guide them?

As more people wanted to ask questions, the conversation extended well beyond the scheduled two hours, ending at 4 PM.

Following this, the female INEB participants had a session with Dharma teacher Yeogwang, who explained and discussed Jungto Society’s social engagement activities. They also watched videos about the various social organizations established and operated, such as JTS, The Peace Foundation, Eco Buddha, and Good Friends.

As the sun set, the dialogue with the female INEB participants resumed at 7 PM. Sunim spoke about the traditional Indian thoughts incorporated into Buddhism, emphasizing the importance of having the right perspective to distinguish between the two. He emphasized the law of dependent origination, the Middle Way, and the Four Noble Truths, explaining why it’s crucial to study the Buddha’s life in depth.

Then, he opened the floor for questions. Over the course of 2 hours and 30 minutes, seven people raised their hands to ask Sunim questions. Among them, a bhikkhuni from Sri Lanka asked about social engagement activities.

How Does Sunim Overcome Burnout?

“It only appears that there are many achievements, but in reality, if we attempt 100 things, only about one succeeds. We don’t talk about the 99 that failed, that’s why it seems that way.

Currently, the farming work at Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center is not successful. Looking at the fields, everyone else has harvested their rice, but we haven’t. Only our rice paddies are diseased. Our farmers leave for retreats in the middle of farming. How can farming succeed this way? Farmers prioritize farming, but when practitioners farm, they constantly leave for retreats and prioritize other tasks, missing crucial times and ruining the crops. We’re not laborers, so we have no other options. Therefore, I can’t evaluate it as successful. Jungto Society continues to experiment. There’s a passage in the Avatamsaka Sutra that says:

‘For bodhisattvas, the Pure Land is not a world already completed, but a realm where bodhisattvas work towards completion.’

The Pure Land refers to Buddhism’s ideal world. In other words, for bodhisattvas, the ideal world is not one that is already completed, but a world where they work towards completion. If I go to hell to save the beings there, then for me, the ideal world is hell.

“I understand. A perfect world where everything is ideal is a world where bodhisattvas have no need to act.”

“If you were asked to choose between heaven and hell, which would you choose?”

“I would go to hell. That’s where I can practice better.”

Everyone applauded and empathized with the bhikkhuni’s resounding answer. Sunim continued:

“In heaven, everything is provided, so there’s nothing to do. In hell, there’s much to do. To practice as a bodhisattva, one must go to hell where everyone needs help. The problem with people in this world is that they do things deserving of hell but want to go to heaven. However, a bodhisattva creates the conditions to go to heaven but willingly goes to hell.”

“I understand well. Thank you.”

The questions continued.

How can ordinary people who don’t know Buddhism understand and practice dependent origination and the Middle Way?

Is the Awakening Retreat program ultimately designed to help people realize the concepts of dependent origination and emptiness? How did the concept of emptiness come about?

How can understanding Buddhism contribute to developing leadership in society?

It’s very difficult to engage in social practice in countries ruled by dictators. How can one combine practice and social engagement in a dictatorship?

In Thailand, women’s ordination is not recognized. As they are not recognized as monastics, they don’t receive support, making it difficult to be active.

How will the direction of The Peace Foundation’s activities change depending on who becomes the U.S. President?

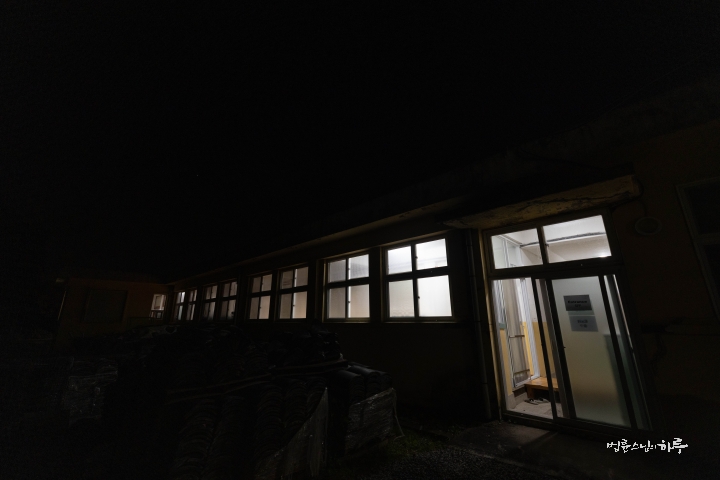

Although some people wanted to ask more questions, it was almost 10 PM. Regrettably, they decided to continue the dialogue tomorrow in Seoul and concluded the program. Sunim smiled and gave instructions for bedtime.

“We’re going to bed a bit late tonight. Tomorrow, you can sleep well in the car on the way to Seoul. We won’t charge for lodging.” (Laughter)

The female INEB participants gathered in groups to share their thoughts before going to bed.

Tomorrow, they will depart from Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center at 3 AM and head to Seoul. In the morning, Sunim will conduct a live broadcast of the Weekly Dharma Assembly. In the afternoon, he will move to the National Assembly to meet with Lee Jae-myung, the leader of the Democratic Party of Korea, and give a keynote speech at the 20th anniversary ceremony of the Political Movement for Unity. In the evening, he will have a final dialogue with the female INEB participants.