Aug 25, 2024 – Day 3 of Psychology Symposium, Dharma Q&A with Korean Residents in Zurich

Today is the third and final day of the psychology symposium in Switzerland on the theme “Tracing the Footsteps of Guilt” (Der Schuld auf der Spur).

After finishing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim left the accommodation and took a walk around the area. The international sculpture exhibition Triennale Bad RagARTz was being held throughout the city, so various sculptures could be seen in every alley. Sunim smiled at some of the interesting sculptures.

After finishing the walk and returning to the accommodation, Sunim had breakfast with Dr. Jeannette Fischer, who would be having a dialogue with him at today’s symposium. While discussing the dialogue to be held this morning, Sunim emphasized giving ample time for questions from the audience.

After finishing the meal and packing all his belongings, Sunim left the accommodation and started the final session of the symposium at 9:30 AM. Suddenly, heavy rain began to fall outside the window.

First, Dr. Sarah El Bulbeisi presented her research on the experiences of Palestinians living in Germany and Switzerland. She explained how they experience discrimination and oppression, and how the resulting pain and trauma have been passed down to the next generation.

Palestinians face social and economic difficulties and prejudice in Germany and Switzerland. In particular, Palestinians who came to Germany in the 1980s had to live in constant anxiety under the threat of deportation due to their limited residence permits. This situation made it difficult for them to integrate socially and freely express their identity. First-generation Palestinians carry the pain of having to forcibly leave their homeland, and this pain has also affected the next generation. The second generation, the children, wanted to understand their parents’ pain and help them, but at the same time, they also experienced difficulties facing discrimination and oppression in society. As a result, the relationship between parents and children was often complicated and difficult, creating emotional distance. Through her presentation, we could fully understand how Palestinians are living in Europe.

From 10:50 AM, Sunim had a dialogue with Dr. Jeannette Fischer. They intentionally scheduled the dialogue with Sunim at the finale of the symposium to comprehensively share Sunim’s insights and wisdom with the participants.

First, Dr. Fischer asked questions about Sunim, such as “When did you become a monk?”, “Why did you become a monk?”, “Was there any opposition from your parents when you became a monk?” Then she asked for his thoughts on the symposium over the past two days and three nights.

“What were your impressions as you watched our presentations and discussions? If there’s anything you’d like to point out to us, please share.”

Sunim briefly shared his thoughts.

“It was good to examine guilt and feelings of guilt from various angles – ethically, psychologically, legally, and economically. I think it was especially good to present on the suffering of sex workers and Palestinians. I also liked that there were so many questions from the audience that time was insufficient.

During the discussion, someone asked if God exists. Whether ‘God exists’ or ‘reincarnation happens’ is a matter of belief. This is not something that can be objectively verified. If one person claims God exists and another claims God doesn’t exist, we shouldn’t approach it by asking ‘Which one is correct?’ We should view it as ‘Their beliefs are different.’ This is because belief is an area of individual freedom.

Is There Something Like Confession in Buddhism Where Sins Are Forgiven?

The priest spoke about confession, saying that confession is about revealing sins. There is something similar to confession in Buddhism as well. In Buddhism, there is no concept of ‘original sin by God’ at all. However, there are precepts that every practitioner must follow. When these precepts are violated, one performs repentance and poṣadha. First, realizing ‘I have done wrong’ on one’s own and reflecting on not repeating the same mistake is called repentance (懺悔). Second, when we live together, even if I have repented for my mistake, others may not know that I have repented. They might think, ‘Why is that fellow practitioner so shameless after breaking the precepts?’ So, once a month, we openly repent in front of all members of the community. We publicly confess to the assembly, saying ‘I have made such and such mistakes, I am aware of them and will improve in the future.’ If the assembly accepts it, it becomes as if it never happened. This is called ‘poṣadha (布薩)’. It could be called ‘forgiveness of sins’ in Christian terms. The difference is that in Christianity, God gives forgiveness of sins, while in Buddhism, the community gives forgiveness of sins.”

“So if everyone agrees, one receives forgiveness of sins?”

“Yes.”

“Then what happens if someone objects?”

“If someone objects, we continue to discuss the issue further. Third, there are times when I have done something wrong but I don’t realize it. In such cases, I cannot repent on my own. So once a year, we request the community like this:

‘If any of you have seen my words or actions that you think violate the precepts, please point them out for my sake. I will listen and improve accordingly.’

This is called ‘pravāraṇā (自恣)’. Pravāraṇā is always done among people living together. Whether it’s five people or ten people, those living together in a community gather to do pravāraṇā. This is because people who don’t live together cannot know each other’s rights and wrongs. Since the person pointing out might have misunderstood, it’s not just about repenting, but also an opportunity to clear up any misunderstandings during this time. After going through this process, no one can raise the issue again with preconceptions. What has been openly repented to the community becomes as if it never happened. If someone raises an issue about something that has already been repented for, it is the person raising the issue who violates the precepts.

Can Suicide Also Be Considered a Sin?

There was also a question about suicide. One might think that suicide is not a sin at all because it’s taking one’s own life, but that’s not the case. Suicide is the same as murder. The only difference is that murder is killing others, while suicide is killing oneself. When someone kills another person, the murderer can be punished, but with suicide, there’s no one to punish because the person killed themselves. That’s why it can’t be punished, but it doesn’t mean suicide is not a sin at all.

Moreover, suicide doesn’t leave the surroundings unaffected. Just as murder causes great pain to many people around, suicide also causes tremendous mental damage to surrounding family members, even more so than murder. For the person committing suicide, it ends at the moment of death, but for the parents, they lose a child; for the spouse, they lose a partner; for the children, they lose a parent, causing immense mental harm. Therefore, suicide should not be viewed solely as an individual matter.”

“That’s right. When someone commits suicide, their family members feel tremendous guilt. It’s as if they think the family has committed a sin and murdered that person.”

“However, ‘death with dignity’ is different in nature from suicide. Death with dignity doesn’t hurt the family, but rather gives them relief. So the act of ending one’s own life is not absolutely wrong. While suicide that kills one’s own life is anti-life, life-prolonging treatment that forcibly tries to save a dying life can also be considered anti-life.”

“Currently, Korea has the highest suicide rate in the world. What do you think is the cause?”

“First, it’s because of the high incidence of mental illnesses, including depression. In Korea, treatment for mental illnesses tends to be neglected. Many people don’t think mental illnesses need to be treated. This is the primary cause. Second, due to the social atmosphere of fierce competition while being conscious of others, some choose suicide when they fail or fall behind in competition.”

After finishing the dialogue with Dr. Fischer, Sunim freely took questions from the audience. While many questions about ‘sin’ and ‘guilt’, the theme of the symposium, were expected, more questions about Buddhism came up instead.

Does the concept of sin include the idea of reincarnation in Buddhism?

I was moved by the fact that Sunim builds schools in conflict areas. How were you able to help children in conflict areas?

How much influence does Buddhism have in Korea?

What positive impact does accepting each other’s differences have on human relationships?

You said that in some cases, like death with dignity, suicide might not be considered a sin. How are life-prolonging treatment and death with dignity handled in Korea?

Tibetan and Bhutanese people seem very peaceful. In what way does Buddhism make them peaceful?

Is there room within Buddhism to enjoy the intense pleasures of life or artistic spirit?

Towards the end of the lecture, questions about Buddhism, guilt, and ego also came up.

How Do People Who Don’t Live in Temples Receive Help from Buddhism?

“There is no special procedure. Traditional temples mostly function by praying for blessings. However, Buddha’s teachings are not about making you be born in a good place after death or receiving blessings. The goal of Buddhism is to reach a state without suffering. I mainly play the role of providing a place where anyone, whether they are Buddhist or not, can talk about their anguish and resolve their guilt and suffering through dialogue. Every Friday, I hold a Dhamma talk where anyone can come and talk about their concerns. This session is open for others to observe as well.”

People from here and there raised their hands to ask Sunim questions.

“In Buddhism, the view is that while ego operates in humans, there is no substance to the ego.”

Sunim continued to briefly answer various questions.

“If we keep emphasizing togetherness, it can have the side effect of identifying others with ourselves. Looking at fingers, we see that all five are different, but they are on one hand. It’s good to say ‘we are one amidst our differences’, but if we only emphasize ‘togetherness’, it tends to move towards uniformity, which can lead to intolerance of differences and conflicts. Conflicts within families often occur because of emphasizing that everyone should be the same.”

As the Q&A continued, Venerable Myohai, who had visited Jungto Society through INEB (International Network of Engaged Buddhists), raised his hand and shared his thoughts.

Sunim answered:

“Meditation is about stopping thoughts. However, as you’ll know if you’ve tried meditation, it’s not easy to stop thoughts. It’s true that all problems are solved when thoughts stop. But it’s not easy to stop thoughts. That’s why acknowledging our differences is most important.

To give an analogy, if I’m wearing red-tinted glasses, this white wall looks red. To someone wearing blue-tinted glasses, this white wall looks blue. So the two people argue, ‘It’s red,’ ‘It’s blue.’ If each person took off their glasses, there would be no need to argue. But we can’t take off our glasses. However, even if we can’t take off our glasses, when someone else says that wall is blue, if we can just acknowledge, ‘It looks red to my eyes, but it looks blue to that person’s eyes!’ – just acknowledging this difference – conflicts won’t arise.”

As they continued talking, it was already time to conclude. Although there weren’t enough questions about sin, guilt, and feelings of guilt, which was disappointing, the lecture ended with a big round of applause as time was up.

The participants also seemed to feel regret, as even after the lecture ended, several people came to Sunim to ask questions individually.

Won’t I Feel Guilty If I Can’t Prevent a Suicide Despite Counseling?

“If such a thing happens despite my best efforts, I would simply have to accept it. There’s nothing else I can do beyond that.”

“Wouldn’t you feel guilty about not being able to prevent their suicide?”

“Feeling guilty won’t help anything. The reason for feeling guilty is overconfidence in one’s own abilities. I can’t solve every problem, can I? We feel guilty when we think we could have solved the problem but feel like we didn’t try hard enough.

For example, if someone asks to borrow $1,000 from me and I don’t lend it, I feel sorry. However, if they ask to borrow $100 million, I don’t feel sorry at all and simply answer, ‘I don’t have it.’ We feel guilty about things we could have done but didn’t, but we don’t feel guilty about things we couldn’t do.”

“Thank you. That was very helpful.”

After greeting the symposium participants, Sunim left the venue and moved to the lunch location with Venerable Myohai.

Venerable Myohai is very interested in engaged Buddhism and runs a meditation center in Switzerland. After having a two-hour conversation over lunch, they took a commemorative photo together.

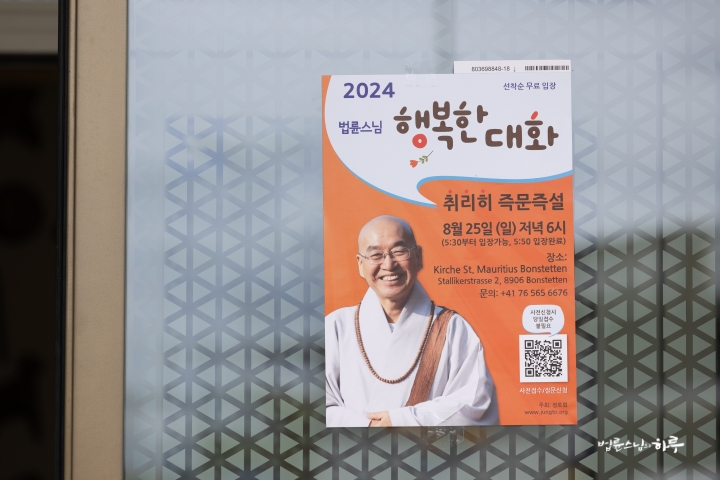

Sunim departed from Bad Ragaz at 2:40 PM and headed to Zurich to give a lecture for Korean expatriates.

After a 1 hour and 20 minute drive, Sunim arrived in Zurich at 4 PM. Today’s lecture is being held at the Catholic Church of Saint Mauritius (Katholische Kirche Sankt Mauritius), located in the southwestern outskirts of Zurich city center.

Upon arriving at the venue, Sunim first took a commemorative photo with the volunteers.

Volunteers had come from all over Europe, including London, Paris, Italy, and Germany, to help with the event. They shared homemade kimbap and rice cakes before preparing for the lecture.

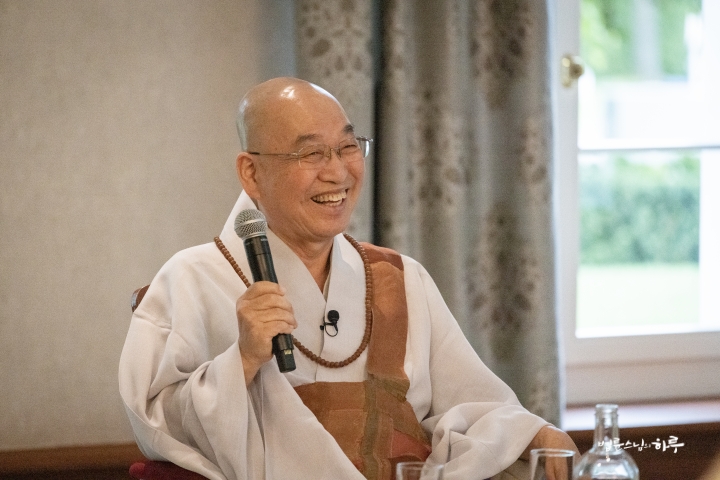

After a brief rest in the waiting room, Sunim headed to the lecture hall at 6 PM. About 80 people filled the church, and the Dharma Q&A session began with enthusiastic applause.

Sunim started with opening remarks, sharing his impressions from attending the psychology symposium over the past three days in a bright and comfortable atmosphere.

“For the past three days, I attended a symposium on guilt, guilt feelings, and sense of guilt organized by the psychology association. I was in charge of the last session, but I felt a bit regretful that I couldn’t have a deep conversation with the audience. Perhaps it was because I’m a foreigner and a monk. It would have been nice if they had asked questions related to the topic, like ‘Does guilt disappear if you repent?’ or ‘Does guilt disappear if you confess?’ Instead, there were many superficial questions like ‘Why did you become a monk?’ or ‘What is Korean Buddhism like?’ So I felt a bit disappointed. Therefore, today, I hope you will feel comfortable asking about any sense of guilt, heavy burden, anguish, or doubt in your mind.”

Then, anyone could raise their hand and have a conversation with Sunim. Over the course of two hours, five people were able to ask Sunim questions. One person sought Sunim’s advice on feeling guilty about not being able to take care of their mother who was living alone in Korea after their father passed away.

I Feel Guilty for Not Being Able to Take Care of My Mother Who Lives Alone

“You can keep crying and living while thinking you’re a bad daughter. If you think you’re a bad person, shouldn’t you naturally be punished? It doesn’t make sense to pray to God to send you to heaven after doing something that deserves hell, right? If you think to yourself, ‘I’m a selfish person who doesn’t fulfill my duty to my parents and only thinks about myself,’ then you should willingly accept punishment. On the other hand, if you don’t think you’re selfish, you don’t need to feel guilty. Which story do you want to hear?”

“I want to hear from Sunim that I’m not selfish and that I should live my own life.”

“Why do you want to hear that you’re not selfish when you’ve already defined yourself as selfish? Isn’t that contradictory? How does your crying help your mother? If you want to help your mother, stop crying here and go to Korea. Do you think your mother would like to see you living here in Switzerland, worrying about her and crying? From your mother’s perspective, would she prefer to see her daughter living in Switzerland, worrying and crying, or living happily and smiling?”

“She would probably like to see me living happily.”

“Not going to Korea to take care of your mother, crying every day and making your mother sad – these actions are not helpful at all.

‘Mom, it’s difficult for me to come to Korea and take care of you. Instead, I’ll send you a lot of pocket money from here. This will be my way of fulfilling my role.’

Shouldn’t you do something like this, or call her every day, or visit Korea once a year? You should do what you can, right?

Living with a smile is what makes your parents feel at ease. As parents, they would prefer their child to be in Korea the most, but even if you can’t come to Korea, they would want to see their child living happily. No parent wants to see their child living in tears.

From my perspective, I’m not sure what you’re trying to do. Doing something that doesn’t help your parents or yourself is simply foolish. If you want to go to Korea, pack your bags and go tomorrow. It’s not selfish if you can’t go. You just need to make a choice and take responsibility for it. If you can’t go, shouldn’t you call your mother and apologize?

‘Mother, I’m sorry that I can’t be there to take care of you now that you’re alone. Instead, I’ll work hard here and send you living expenses every month. I’ll call you at least once every ten days.’

Shouldn’t you say something like this and do the specific things you can do? Are you sending your mother pocket money?”

“Yes, I am sending money.”

“It’s better to find and do what you can in the time you spend crying. Crying and being sad doesn’t help your mother, and it doesn’t help you either. This is what we call ‘foolish.’ Being foolish means you’re tormenting yourself. Let’s say I hit someone. From the other person’s perspective, it’s a bad deed, but from my perspective, it’s a foolish act. When I hit the other person, I just swung my fist once, but the consequence is going to jail for assault. This is how you harm yourself, hurt yourself, and torment yourself – that’s what we call foolish.

Harming others, hurting others, or tormenting others is called bad deeds. Bad deeds, from your own perspective, are actions that cause harm to yourself. That’s why we express it as foolish. In Buddhism, we don’t express it as bad deeds but as foolish acts. We can say that when you awaken from foolishness, you stop doing things that harm yourself. That’s why in Buddhism, we don’t usually say ‘do good deeds,’ but rather ‘act wisely.’ In other words, it means to stop foolish acts. What you’re doing now is foolish. You’re doing something that doesn’t help anyone.

If you keep crying, you might get sympathy from others. But if you really care about your mother, instead of crying, you should send her pocket money, contact her regularly, or do things that actually help her. If you think it’s better to go to Korea, then go willingly.

However, if you go to Korea in your current foolish state, when things don’t go as you expect, you might not find the cause in yourself but blame your mother. This is because you’ll think you returned to Korea because of your mother. You might think, ‘If it weren’t for my mother, I would have lived in Switzerland as I wanted, but because of her, I came back to Korea and this happened.’ There’s a risk of transferring all responsibility to your mother.

So even if you go to Korea, you should decide to go on your own. Even if you stay in Switzerland, you should decide to stay on your own. This way, you take responsibility for what happens afterwards. But your current way of thinking is extremely irresponsible. That’s why you’re acting so foolishly now.

Your mother is living well even without you. It would be nice if her daughter could be by her side, but not everything in life can go as we want, right? Even if her daughter isn’t by her side, she’ll live well with the pocket money you send. So this is not your mother’s problem, but your own. You want to keep living in Switzerland, but you also want to be called a filial daughter. Trying to do both is greed. So choose one for yourself.

It’s not selfish to continue living in Switzerland. As long as you’re not directly harming others, you can live according to your own will. And for your mother, you can only substitute by providing financial support or contacting her regularly. I hope you live your life with this perspective.”

“Yes, I understand.”

“When you become a parent, there’s usually something you desperately want for your child. But you shouldn’t think you’ve committed a sin just because you can’t fulfill your parents’ desperate wish. That’s just your parents’ wish. However, you shouldn’t argue, ‘Why do you want such a thing from me?’ That attitude shows a lack of understanding of your parents’ feelings. Your parents and you simply have different thoughts. You should accept that your parents can think that way.

‘Mother, is that what you think? But I’m sorry. I can’t do that.’

You should be able to say this and go your own way. If children had to live only as their parents wanted, they wouldn’t be free individuals but slaves. Whether you’re a slave to a king or to your parents, a slave is a slave. Of course, you can go to Korea and live as your mother wants. But even then, you should go because you choose to, not because your parents demand it. That’s how you can be the master of your own life.

If you keep crying in Switzerland without being able to go to Korea, you might think, ‘She thinks about her parents so much, she’s such a filial daughter.’ Not at all. From my perspective, you’re full of greed.

If someone asks, ‘I want to get married and also become a monk, which should I do?’ you might think, ‘This person is having such good thoughts that they’re considering becoming a monk.’ This person is suffering because they want both the honor of becoming a monk and the fulfillment of worldly desires through marriage. It’s the height of greed. They’re not having good thoughts. To have one thing, you must be able to let go of another. You should be willing to take responsibility for what you let go of.”

“Thank you.”

“Later, when your mother passes away, you shouldn’t cry and be sad. Your mother’s passing is not your fault, but because her life span has ended. You just need to take responsibility for your choices willingly. You should live your life happily with this perspective.”

The questions continued. After conversing with five people, Sunim gave his closing remarks.

“Fundamentally, there’s nothing to be troubled about. What do you think is troubling? Is meeting troubling? Is parting troubling? Of course, if you can’t eat, get beaten by others, or suffer sexual assault, you’ll experience tremendous physical and mental pain. But apart from such cases, most of our experiences are not things to be troubled about.

How to Live a Life Without Suffering

You’re currently suffering because things don’t go as you want, or because you can’t do what others want you to do. In the end, you’re suffering because things don’t go your way. But how can everything in the world go exactly as you want?

As long as it doesn’t violate the five precepts, you can choose and follow your own path. Also, regarding other people’s lives, as long as it doesn’t violate the five precepts, you shouldn’t interfere, even with your children. If parents have too high expectations for their children, it becomes a heavy burden for the children. This distorts the children’s lives. When they become adults, you should let them freely pursue their own will. If they always think, ‘How can I satisfy my parents?’ to look good to their parents, they become people who can’t overcome difficulties in their own lives.

So you shouldn’t have excessive expectations for your children. Excessive expectations become a heavy burden for children and act as an obstacle to pursuing their own will. If you’ve raised them until they become adults, you’ve done your job as a parent. You should let your children go, saying, ‘Whatever you become from now on, live your life as you see fit.’ Even if they ask, you should say, ‘Do as you think best.’ If they still ask for advice, you should only say something like, ‘Well, I’m not sure if this will help, but this is what I think.’ Having too much interest in your children can actually become an obstacle for them. I hope you remember this point.”

As soon as the lecture ended, a book signing session followed. Many attendees received Sunim’s signature on his books and exchanged brief but warm greetings with him.

After all the audience members had gone home, Sunim had a heart-to-heart session with the volunteers. They shared their experiences and impressions, discussing what they felt through today’s lecture.

“I’m so happy to see Sunim in person, whom I’ve only seen online before. I haven’t been able to practice diligently lately, but after seeing Sunim this time, I’ve decided to practice more diligently.”

“Sunim is the person I want to thank the most in my 50 years of life. I’m so grateful for this opportunity to meet Sunim in person. Thank you so much for coming all the way to Switzerland.”

“I’m so happy that our family could listen to Sunim’s words together. Thanks to Sunim’s teachings, my mind has become much more at ease. I will continue to practice diligently in the future.”

Kwon Beopmi, who accompanied Sunim for the past three days and oversaw the event, also shared her thoughts.

“I gained a lot of insight during the three days I spent with Sunim. It felt like I had done ten thousand prostrations, experiencing the disappearance of mental afflictions.”

All the volunteers were overjoyed to have the opportunity to have a direct conversation with Sunim after successfully concluding the lecture.

“Everyone, thank you for your hard work. I appreciate it.”

After expressing his gratitude to the volunteers, Sunim moved to his accommodation. The volunteers restored the used church building to its original state and cleaned up.

After 9 PM, they arrived at the home of Kim Eungsoon, a Jungto Society member living in Zurich, had a late dinner, and concluded the day’s schedule.

Tomorrow, Sunim will depart from Zurich in the morning to visit a foundation in Basel that helps female immigrants become self-reliant. There, he will have conversations with immigrants from various countries. In the afternoon, he will cross the German border to Frankfurt, and in the evening, he will give a Dharma Q&A lecture for Korean expatriates living in Frankfurt.