Aug 12, 2024 – Farm Work, Dharma Talk for Leading Members

Good morning. A new day has dawned at Dubuk Retreat Center.

Sunim began the day with farm work after finishing his morning practice and meditation. Today, he decided to prepare the vegetable garden for planting fall cabbages and radishes. The Haengja trainees from the practice team also helped with farming, armed with shovels.

First, he removed stones from the garden and piled larger ones along the edges to create a border. Sunim carefully examined the shape of each stone and used a hammer to firmly embed them in the ground to prevent collapse. After working for a while, the garden’s boundaries became clearly defined.

Sunim picked up a shovel but found he couldn’t dig due to knee pain.

“Oh my, I can’t do any digging now. Haengja, could you please do the digging?”

Sunim continued creating the garden border with stones while the Haengja trainees tilled the soil with shovels.

After turning over the small vegetable patch once, sweat poured down like rain.

When they finished tilling the soil, Sunim said:

“We’ll be planting cabbages and radishes, so add plenty of fertilizer to the soil.”

The Haengja trainees generously spread fertilizer over the garden.

They picked up shovels again and thoroughly mixed the fertilizer with the soil. The garden quickly became rich and fertile. To allow more sunlight into the garden, Sunim trimmed jujube tree branches hanging over the wall.

Finally, they created ridges for planting cabbages, completing work on one garden.

“Good job, everyone.”

They then moved on to the next vegetable patch. They turned over the soil, spread fertilizer, and created furrows.

They moved to yet another patch to turn over the soil and spread fertilizer.

Many cockscomb flowers had grown naturally, so they thinned them out.

After tidying up the flower bed overgrown with cockscomb, it was already 8 AM.

“The sun is already getting strong. Let’s finish up for today and wrap things up.”

After washing and neatly arranging the tools they had used, they each drank a cool glass of water and concluded the morning’s work.

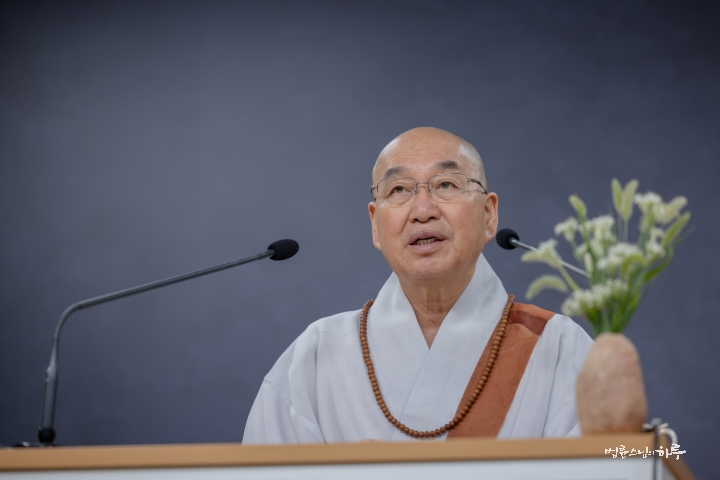

After finishing the farm work, Sunim began a Dharma talk for leading members of the daytime group at 10 AM. Once a month, leading members gather to discuss difficulties they face in their Jungto Society activities with Sunim.

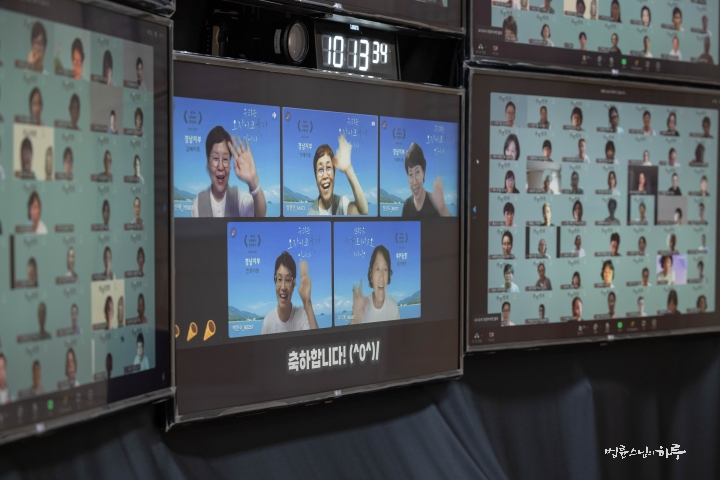

Before the Dharma talk, they took time to welcome new leading members. Following a welcome speech by the Jungto Society president and a video welcoming the new leading members, everyone applauded joyfully.

Next, the leading members requested a Dharma talk from Sunim with three full bows. Sunim mentioned the intense heat wave and the resurgence of COVID-19, urging everyone to take care of their health.

“Although Ipchu, which marks the beginning of autumn, has passed, the heat wave is still raging. I hear that in Seoul, tropical nights continue even at night. In rural areas, the temperature drops to about 21 degrees Celsius in the early morning, making it a bit chilly to sleep without a blanket. However, during the day, it’s so hot that it’s almost impossible to work as it feels suffocating. Most Jungto Society members don’t work in rural areas, so the chances of heat-related illnesses are low. But if any of you work outdoors during the day, please take breaks frequently or avoid working during the hottest part of the day if possible.

I also did some work at the Dubuk Retreat Center farm yesterday and today. Until 9 AM, it was still manageable to work. But after 10 AM, it felt suffocating. The midday sun was really hot and the temperature was high. Everyone, please be careful in this heat wave.

I’ve returned to my daily routine of farming after a long time. As soon as I wake up in the morning, I spend about two hours tidying up the vegetable garden and flower beds. Farming requires consistent daily effort, but after traveling abroad and suddenly starting to work, my back hurts, my chest hurts, and I’ve got blisters on my hands. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I lived leisurely in the countryside, farming like a retired person. It feels like those good times are over. (Laughs)

I hear that COVID-19 cases have increased sixfold in just a month, so everyone needs to be more careful and wear masks. In the past, there would have been strict controls, but now it seems we’re almost defenseless. Since the COVID-19 virus often leaves aftereffects, please be careful not to get infected.

Especially today, I’d like to congratulate those of you who have become leading members after completing the long process of graduating from Jungto Dharma School, graduating from the Sutra Course, participating in the 1000-Day Practice, attending the Enlightenment Retreat, receiving training as leading members, passing the evaluation, receiving education as Korean Minutemen for Peace and Unification, and participating in the precept ceremony. I warmly welcome the approximately 130 new leading members who have become leading members through this tremendous process, as if passing a difficult exam, even though you don’t receive a salary.”

Sunim then gave a detailed report on the results of his visit to 10 Southeast Asian countries over the past month. After the report, he engaged in a dialogue with those who had requested questions in advance. Three people pressed the raise hand button and asked Sunim questions. One of them sought Sunim’s advice on difficulties faced while serving as a facilitator for the Buddhism course.

Even Good Things Become Painful When Done with Greed

My second question is about feeling afraid when I take on responsibilities due to my perceived lack of computer skills. I could just not do it, but when they’re looking for someone to take on a role, I often raise my hand. Then I worry and torment myself. During the last opening ceremony, you said, ‘I’ll find many volunteer opportunities in Bhutan, so prepare yourselves.’ At that time, I caught myself thinking, ‘Should I get an excavator license?’ and started tormenting myself again. What should I do about this tendency?”

“It’s natural to shed tears or feel sad when you hear about the difficult lives of Buddhism course students. We can’t control these feelings. However, as practitioners, we need to maintain equanimity. We shouldn’t get too excited, too sad, or too depressed. Even if it’s not always possible in reality, that’s the goal. As a Buddhism course facilitator, you need to guide others, so when you feel like crying, you should take a deep breath and practice calming your emotions.

If you had no role, people around you might just think you’re an emotionally sensitive person. But when you take on the role of a facilitator, it’s not ideal to cry along with others and make everyone else cry too. It’s not causing major harm to the students, but it’s not desirable either. So you need to observe yourself and try not to get too emotionally excited.

Regarding your computer skills, if you’re not good at it, don’t be afraid. Just take some time to learn how to use a computer. Saying ‘I’m not good at it’ without trying to learn means you don’t want to learn. It’s not that you can’t use a computer; you just don’t want to learn how to use it. Of course, if you’re suddenly asked to do computer work, you can say ‘I’m not good at that.’ But if you keep saying ‘I can’t do that job,’ it means you’re not willing to learn it. So just learn the skills necessary for your role and try it out. We’re not asking you to do extensive editing like the Sunim’s Day production team or the video media team. You just need to learn enough to facilitate the Buddhism course.

If you’ve volunteered for a role, you should approach it with the mindset of ‘Let’s use this opportunity to learn the skills needed for this role’ instead of being afraid. Being afraid doesn’t help you acquire skills. If you really dislike learning that skill, or if you try it and find it doesn’t suit you at all, then you should refrain from taking on that role. For example, if they’re recruiting leading members and you want to raise your hand, but you have to work evenings at your job and absolutely can’t make time, then you shouldn’t volunteer. It’s not right to volunteer and then say ‘I absolutely can’t make time.’ There’s no need to keep getting caught up in things you can’t do.

Learning to operate an excavator, wallpapering, painting, or carpentry – these are all things you can do if you just make time. We even have a carpentry class at Dubuk Retreat Center. The volunteer work in Bhutan doesn’t require professional skills – it’s just sawing, planing, and making kitchen furniture. These days, don’t most people do a lot of these things at home? Once you call a professional technician, they charge hundreds of thousands of won. So people end up buying machines and doing repairs themselves. Especially in the United States, where professional labor is expensive, every household has all kinds of machines. If you rely on professional technicians for even simple repairs, you end up becoming someone who can’t even hammer a nail.

“Even if you go to volunteer in Bhutan, you don’t need special skills – just knowing how to do simple repairs is enough. If a large building needs to be constructed, that’s not a job for volunteers but for professional technicians. However, the volunteer work you’ll be doing is like painting a wall – it only requires that level of skill. Of course, Bhutan has many skilled professionals including carpenters. But what JTS wants to do in Bhutan is to create a spirit of volunteerism. We’re promoting a movement of ‘Let’s take care of our own neighborhood and repair our own homes,’ so if you go and help a little, it becomes much easier for the villagers to participate in this movement. If we pay professional technicians to do everything, the villagers won’t be able to repair things when they break down later. So initially, volunteers go to help, but in the long term, volunteers won’t be needed. JTS’s goal is for villagers to learn and develop their village on their own.

Even with this proposal, villagers are hesitant at first because they think such work should be done by professionals. But when I went to Bhutan and saw for myself, there were many things that anyone could learn to do easily without professional skills. So it’s necessary to create an atmosphere where villagers think ‘Oh, we can do this too’ by showing them you directly fixing and repairing things. This is why I’m saying volunteers are needed from this perspective.

But don’t be greedy. Even good deeds become painful if you’re greedy. Trying to do more than you’re capable of can all be considered greed.”

“Thank you. Your words about practitioners needing to maintain equanimity really resonated with me. And after hearing that even good deeds become painful if done out of greed, I realized I need to examine whether I’m acting out of greed.”

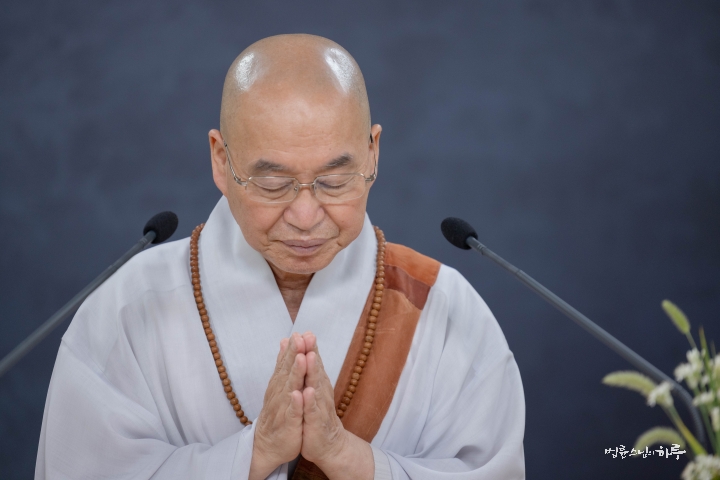

The questions continued. After answering all the questions, it was almost 12 o’clock. The live broadcast ended with a promise for the next dharma talk.

When leaving the broadcasting room, it was sweltering hot with the daytime temperature reaching 35 degrees Celsius. Sunim spent the afternoon working indoors to avoid the heat.

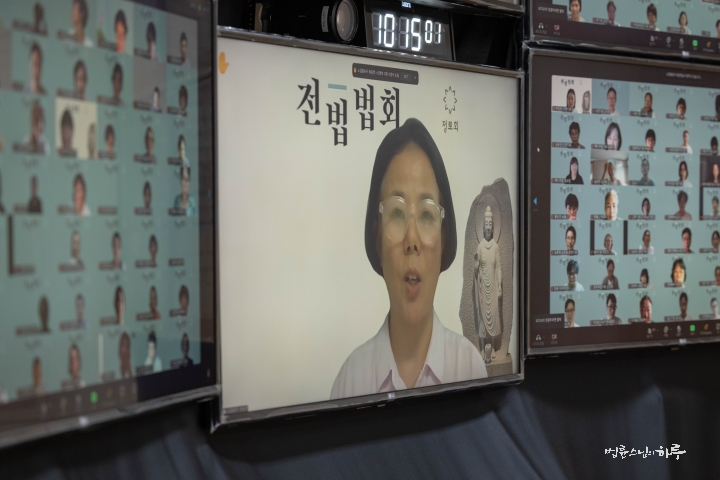

As the sun set, from 7:30 PM, Sunim held a live dharma talk for the evening group of dharma propagation members at the Dubuk Training Center’s broadcasting room. After all leading members entered the video conference room, Sunim greeted them and gave a detailed report on his visit to 10 Southeast Asian countries over the past month.

Then, he took questions from three people who had requested in advance, followed by an open discussion where people could raise their hands to talk with Sunim. One of them suggested that to achieve sustainable development in Bhutan, it might be necessary to educate and train volunteers in advance, and asked for Sunim’s advice.

Should we educate and train volunteers for sustainable development in Bhutan?

“Yes, that’s a good suggestion. We plan to do that in the future. For now, I’ve asked you to start with mental preparation.

When I surveyed Bhutan, I realized that volunteers don’t need to build new houses. This is because building a new house requires a carpenter, not volunteers. So, we’re having professional carpenters build houses, and villagers take turns doing communal labor, with a few people working each day.

However, when you go inside the houses where villagers currently live, you’ll find the kitchens filled with smoke and no partitions in the rooms. Grandparents, parents, and newlywed couples all live together. In such houses, we need to at least install some partitions.

But because the villagers have lived this way for so long, they can’t think of how to improve their situation. So when asked to renovate their homes, all they can think of is imitating rich people’s houses. However, from our perspective, to prevent smoke in the kitchen, there’s no need to imitate wealthy homes; we just need to build a chimney to let the smoke out. Most houses have water outside, so we could do some cement work to bring water into the kitchen, or build more shelves in the rooms so that belongings can be neatly organized instead of scattered on the floor. These are the kinds of ideas we need.

Remember how we used to store rice in sacks, and then rice containers became popular? There was a time when newlyweds were expected to have a rice container. Later, it was “you need a fan,” “you need a refrigerator,” “you need a washing machine.” In Bhutan, if you go to a wealthy home, you’ll see refrigerators and washing machines. But poor homes don’t even have fans yet. Since we’ve already gone through this process, we should have many ideas on how to improve the basic living conditions of the Bhutanese people. For this, we need to learn some basic skills in advance. For example, to build shelves inside a house, you need some carpentry skills. To fix the floor, you need to know how to apply cement. To build walls, you need to learn how to make mud walls with soil and stones. To lay water channels, you need to know how to make formwork. Because they can’t make proper formwork, the water channels end up being thick in some parts, thin in others, high in some places, and low in others. To do these things, you need to learn these skills in advance. For more advanced skills, it would be great if you could operate an excavator. We need a lot of excavators to build roads and water channels. Driving trucks, doing electrical wiring – these are all necessary skills. Nowadays, even Koreans do a lot of home repairs themselves. That’s the level of skill you need to acquire.

Currently at the Dubuk Retreat Center, we’re planning to experiment for about a month with a team consisting of one or two people who can do carpentry, one or two who can operate an excavator, and one or two who can drive trucks. By forming such a team and actually doing the work in Bhutan, we’ll be able to figure out how many people with what skills we need. Based on that, we can gradually expand and recruit more people. For example, when we need carpenters, we’ll be able to determine whether they need a month of training or six months, comparing various scenarios to establish a system.

For now, please try repairing houses, using hammers, operating brush cutters, and practicing various skills at the main temples across the country. We’ll need brush cutter operators in Bhutan too. Young people in Korea these days really don’t know how to do anything. They can’t even use sickles or hoes, which everyone used to be able to do. So, people over fifty might actually be more suitable for sustainable development projects than young people. Women can also teach cooking to villagers in Bhutan. They have very few vegetables there. There aren’t many side dishes to eat with rice. So, teaching them how to make kimchi, how to grow and harvest various vegetables – these would all be helpful. They only have a few types of vegetables like potatoes, onions, and cucumbers. It’s similar to how it was in rural Korea when we were growing up. So there’s a lot for women to do in Bhutan. Even well-off people in Thimphu are interested in learning how to make kimchi or soybean paste. Korean food is becoming popular in Bhutan these days. So when you go to Bhutan or Southeast Asia for volunteer work, you can fully utilize your talents.

Also, because transportation in Bhutan is so poor, there’s nowhere to sell produce, whether it’s from the wild or from farms. The population is also dispersed, with only about 17,000 people living in an incredibly vast area. The distance between villages is about a one or two-hour drive. So we need to come up with alternatives like drying agricultural products, making pickles, or making tea. This is because in Bhutan, to sell agricultural products, you have to travel for about 10 hours by car to reach Thimphu, where there’s a market worth selling to.

I think that when many people go together to volunteer, a lot of good ideas will emerge. Initially, we’ll start with a few necessary people doing pilot projects, and if the Bhutanese government recognizes the results, we might be able to recruit volunteers on a larger scale within a year.

This approach can be applied to many other countries in the future. The president of a Buddhist university in Battambang, Cambodia, said he’d like to apply this method in Cambodia, and an organization in the United States inquired why we weren’t applying for funding, saying it was such a great project. I replied that we’re still in the experimental stage and will make proposals after sufficient experimentation, but this shows that this project can be expanded throughout Southeast Asia.

The most important thing right now is trust. If we can create a sample that anyone who sees it judges as “This project is low-cost but really effective,” the spread of this project will be very fast, and securing funding will become easier. So creating a sample is crucial right now.

In the second half of the year, we’ll need to recruit a few volunteers and actually go for the first round of service. Then the volunteers will come back with suggestions. We can’t come up with solutions simply by looking once and saying “We should do this” or “We should do that.” We need to go to the site, examine the terrain and climate conditions, and then suggest what method is better. We shouldn’t assume that the Korean way is always effective.

Livestock farming is also necessary in Bhutan. This is because in addition to farming, they need some additional income from raising chickens or goats. Cash crops, including fruit trees, are also needed. It’s difficult to select volunteers who can develop these areas now, and there aren’t many people with these skills. So for now, as opportunities arise, one or two people should come with me each time I go to Bhutan to experiment together and find suitable methods. For example, to change the rice planting method, someone with farming skills needs to live in Bhutan for about a year, planting rice and harvesting with the villagers. Because the new farming method hasn’t been verified for yield yet, you can’t convince people by just looking at a field once and giving instructions.

So when you retire, you should learn Korean methods of seedbed preparation and rice planting, or study various environmental farming methods. Then you need to actually go to Bhutan, secure a plot of land, and do demonstration farming. Villagers need to see with their own eyes the comparison between the new method and their own method to determine which is more effective before they’ll follow suit.

As the questioner suggested, we definitely need a training process and need to select people in advance. We’ll gradually set up such processes in the future.”

“I’ve listened carefully to your words, Sunim. If possible, I’d like to be the first to be used in Bhutan’s sustainable development project.”

“Thank you. I hope all of you will have hope and try to plan a new life.”

The questions continued.

After answering all the questions, Sunim gave a closing remark. When the Dharma talk ended, it was past 9 PM.

Tomorrow, a few members from the community Dharma teachers’ group will visit the Dubuk Retreat Center to help with farming. In the morning, Sunim will do farm work with the Dharma teachers, have a meeting in the afternoon to prepare for the India pilgrimage, and then do more farm work at dusk.

A Day in the Life of Sunim is translated by AI, edited by volunteers