Jan 26, 26 – Day 3 of the India Pilgrimage, Pragbodhi Hill

Hello. Today, we traveled eight hours from Varanasi to Bodh Gaya to visit Pragbodhi Hill, and there was a welcome ceremony at Sujata Academy.

Today’s schedule began with a long journey. After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim prepared to leave Varanasi, still shrouded in darkness, for Bodh Gaya. The pilgrimage group also loaded their luggage onto the buses that had arrived at each accommodation. They loaded rice, water, cooking utensils, and personal belongings to be used during the pilgrimage and departed from Sarnath at 4:30 AM. From here, they would travel by bus for about seven hours to Gaya Mountain near Bodh Gaya. The pilgrimage group conducted morning prayers and meditation inside the moving vehicles.

About an hour and a half after departure, Bus No. 4, which Sunim was riding in, suddenly stopped. The bus headlights had malfunctioned. Since darkness had not yet lifted, it would be dangerous to continue driving.

Dharma Teacher Bogwang went to look for someone in the village who could repair the vehicle. He stopped by a tea shop that had opened early to ask for help. However, it was too early to reach any technician who could fix the vehicle. When Sunim’s bus stopped, calls came in from the Dharma teachers leading each vehicle.

“Sunim, should we wait until Bus No. 4 is repaired and go together?”

“No. All other buses should depart first so there’s no disruption to the pilgrimage schedule. Bus No. 4 will depart as soon as it’s repaired.”

All vehicles except Bus No. 4 departed for Gaya Mountain. About an hour after stopping the bus, dawn began to break.

“Dawn is breaking. Now we can drive without headlights, so let’s depart. If we’re any later, the pilgrims on Bus No. 4 won’t be able to visit Gaya Mountain.”

“Yes, Sunim. But the driver says not only the headlights but also the engine needs inspection. It seems departure will be delayed further. Also, Sunim, if we’re delayed more, we won’t be able to make it to the Sujata Academy welcome ceremony on time. You must be present at the welcome ceremony.”

Sunim had to consider both the schedule of the Bus No. 4 pilgrims and the welcome ceremony time. Sunim asked Dharma Teacher Bogwang to find a taxi in the village. The plan was to stop Bus No. 10, which was at the rear, catch up to it by taxi, then switch to the accommodation team’s car midway to make it to the welcome ceremony on time.

Sunim packed only the immediately necessary kasaya, bag, and hat. Fortunately, they were able to contact a taxi driver in the village and took the taxi. In the distance, Bus No. 10 was waiting on the roadside. Sunim boarded Bus No. 10 and headed for Gaya Mountain.

After about an hour and ten minutes, the bus arrived at a village called ‘Shiaram.’ Police officers were waiting there for Sunim. The Indian Ministry of Culture and Tourism had sent an official letter to Gaya City requesting ‘cooperation in guiding the JTS pilgrimage group,’ and the Gaya police had agreed to escort Sunim. Soon after, the accommodation team’s car also arrived, and they headed to Gaya Mountain with police guidance.

After many twists and turns, they arrived at Gaya Mountain around 11:20 AM. If they had arrived just a little earlier, Sunim could have climbed the mountain with the pilgrimage group, but instead, he greeted the pilgrims descending from the mountain at the village entrance.

At noon, Sunim headed to Sujata Academy with the pilgrimage group that had descended from Gaya Mountain. The Gaya police provided traffic guidance all the way to Sujata Academy.

After about 20 minutes of travel, steep and rugged rocky mountains appeared. They had arrived at Dungeshwari. Going a little further, they could see a yellow arch in the distance with “Welcome to Sujata Academy” written on it. In front of it, children dressed in traditional red, green, and white costumes stood neatly in line to greet the pilgrimage group.

On both sides of the road, Sujata Academy students and villagers lined up in long rows. Parents holding their children’s hands, children looking on with curious eyes, and even people standing on walls were all waiting for the pilgrimage group. This path, usually the children’s route to and from school, had become a festival ground just for today. The students stood with bright expressions, holding yellow marigold flower garlands in their hands.

As Sunim and the pilgrimage group got off the bus and slowly began walking toward Sujata Academy, the sounds of trumpets, drums, and children’s cheers rang out, and flower petals scattered from the sky.

The students placed flower garlands around the neck of each pilgrim. The children’s shy smiles silently conveyed the message “Welcome.” The pilgrims also beamed at the children. The children themselves were a gift.

The welcome ceremony prepared by the Sujata Academy students was simple but warm. Amid the falling flower petals, starting with Sunim, about 500 pilgrims slowly entered Sujata Academy.

Sunim and the pilgrimage group paid their respects at the Dharma hall and offered prayers at the stupa of the late Seol Seong-bong, who had passed away while volunteering at Sujata Academy. Warm tea and snacks were prepared in the Mango Garden, allowing the pilgrims to rest briefly after their long journey.

Once the pilgrimage group settled in the playground, the welcome performance began. As the first act, all students danced together. The pilgrims also stood up and danced with the children.

In the grade-level performances that followed, the children showcased their practiced skills with confident expressions.

Thanks to the welcome ceremony, the pilgrimage group regained energy in their tired bodies and minds. After the performance ended, they gathered in the playground. Sunim asked the pilgrims.

“Have you ever been welcomed this enthusiastically in your life?”

“No!”

“I heard the Sujata Academy students have been preparing for this welcome ceremony for a month. The children’s talents are remarkable. Did you enjoy it?”

“Yes!”

“There will be performances at the school anniversary ceremony the day after tomorrow as well. Now, this mountain spread out like a folding screen before you is Pragbodhi Hill. It means ‘the mountain where the Buddha practiced before attaining enlightenment.’ This is where the Buddha practiced asceticism for six years. The place where he attained enlightenment is Bodh Gaya, about 8km from here, and we plan to walk there tomorrow morning. Now, let’s climb Pragbodhi Hill.”

The pilgrimage group left Sujata Academy and began climbing Pragbodhi Hill.

After arriving at the foot of Pragbodhi Hill and meditating briefly, Sunim explained about the mountain.

“When the Buddha climbed Gaya Mountain and looked around, he saw a mountain on the east side of the Nerañjarā River. Seeing that mountain, the Buddha thought, ‘This would be perfect for practice.’ This mountain we’ve climbed is that very place. Sujata Academy is at the foot of this mountain. Originally, this was a charnel ground called Sitavana, where dead bodies were disposed of. That’s why this area is still called Dungeshwari. According to historians, the word ‘dunge’ contains the meaning of ‘impure.’ It doesn’t mean unhygienic or dirty, but rather an impure place, meaning an unholy place.

Because it was a charnel ground area where corpses were disposed of, people considered this place impure and rarely visited. For precisely this reason, the Buddha thought it was suitable for practice. The Buddha crossed the Nerañjarā River and came to this Dungeshwari, determined to undertake ascetic practices that no one in this world had ever attempted. It took six years from when the Buddha left Kapilavastu until he attained enlightenment, and records say he practiced here for those six years. Of course, before coming here, the Buddha spent time visiting various teachers and studying, so it’s difficult to say he spent the entire six years here. However, since this was where he stayed the longest and practiced most intensively, it’s remembered as the place of his six-year ascetic practice.

According to Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha seems to have almost completely let go of thoughts about eating, clothing, and sleeping. Initially, he ate one meal a day, then gradually reduced it to one date a day, one date every three days, and eventually just one date a week. As he barely ate any food, he lost all his weight, becoming like bones covered with skin, and his skin became so wrinkled that his hair would fall out at the slightest touch. The image of the six-year ascetic practice that we commonly see, with “the skin of the belly stuck to the backbone,” depicts this very period. Since there were hardly any people around, he wore almost nothing, and he slept under trees or in caves while dedicating himself to practice.

Why Did the Buddha Abandon This Path After Six Years of Ascetic Practice?

The basic principle of ascetic practice lies in deliberately not taking care of the body to avoid seeking comfort. One must not think about what to eat. While we choose flat spots when sitting on the ground, a practitioner must not do so. Like a cow dropping to the ground, one must simply plop down. When sitting, one must sit without preparing a place, not wash the body, and not eat soft food. These were the principles of ascetic practice that practitioners followed at that time.

However, after six years of ascetic practice, the Buddha realized on his own that there was no reason to persist in such austerities. So to restore his body, he drank rice gruel and bathed in the flowing water of a stream. When his fellow practitioners saw this, they immediately concluded, “Gotama has given up his practice.” At that time, it was believed that to attain enlightenment, one must not have any attachment to the body. When Gotama practiced severe austerities according to the principles, his fellow practitioners respected him and had great expectations, saying, “Gotama will surely attain enlightenment.”

According to scriptural records, the Buddha remained so still in meditation that moss grew on his body and insects began to inhabit it. Even when birds came to peck at the insects, he remained completely motionless. Children who followed the untouchables who disposed of corpses would sometimes come near this charnel ground to search for valuables among the bodies or to graze their goats. Since the Buddha remained motionless with moss growing on his body, from a distance he must have looked like a statue. There are records of children making bets, saying “That person is dead,” “He’s still alive,” or “He’ll die soon.” To check whether he was alive or dead, they would throw clods of earth at him, and some children would come close and stick twigs in his ears to see if he was dead or alive. Despite this, the Buddha endured the pain steadfastly without moving at all. The fact that such records remain shows how extreme his ascetic practice was. However, even after six years of asceticism that no one could imitate, enlightenment did not come. At that time, it is said that Mara, the demon, whispered to the Buddha.

‘The word enlightenment exists, but there is no such state in reality. The word nirvana exists, but no one has attained it. If you die while practicing like this, it will be meaningless. So stop your practice and return home to offer sacrifices to the gods. Then you will become a wheel-turning monarch who unifies all of India. Go back home now.’

In the scriptures, such temptations are expressed through the name of Mara. Mara is also called ‘Papman’ and is recorded as ‘Mara.’ The Mara mentioned here is different from the evil ‘devil’ in Christianity. Among the heavenly realms, the closest to the human world is the Heaven of the Four Kings, which is symbolized by the Four Heavenly Kings Gate that we see when entering a temple. Above that are Trayastrimsa Heaven, Yama Heaven, Tusita Heaven, and Nirmanarati Heaven, with the highest being Paranirmita-vasavartin Heaven. Thus, there are six heavenly realms in the desire realm.

Among these, the best heavenly realm—where whatever one desires comes true and can be changed at will—is Paranirmita-vasavartin Heaven. The king of that realm is called the Lord of the Paranirmita-vasavartin Heaven, commonly referred to as Mara. This doesn’t mean he is an evil being. However, this Mara obstructs the attainment of liberation and nirvana. He is a being who prevents one from becoming free from desires. As the highest authority responsible for maintaining order in the desire realm, he is called Mara in that sense. Mara’s temptations appeared even when the Buddha renounced the world.

‘Born as a prince, you can live so comfortably. Why would you enter the forest to suffer among poisonous insects and wild animals? Stop these useless thoughts and return home quickly. Then you will become the universal monarch of India.’

Whenever such whispers arose, the Buddha would reaffirm his resolve, saying, ‘Don’t speak such words. I will practice with fearless determination and attain liberation.’ From today’s perspective, this could be seen not as Mara but as an ‘inner voice.’ It’s similar to how, even when we decide to renounce the world, a thought arises in a corner of our mind: ‘Wouldn’t it be better to get married and live a normal life?’ However, those who recorded the Buddha’s life felt it inappropriate to express that the Buddha experienced such inner conflicts. Therefore, they explained all such mental wavering in the form of ‘Mara’s temptations.’ This is why Mara’s temptations appear repeatedly throughout the scriptures.

If after six years of desperate practice, the possibility of achieving enlightenment still seems out of reach, we too would wonder, ‘Does enlightenment really exist?’ The Buddha experienced the same doubt, wondering, ‘Is there really such a state as enlightenment?’

The Third Way Discovered at the End of Asceticism: The Middle Way

However, the Buddha strengthened his resolve, saying, “Mara, begone!” And he spoke these words to Mara:

‘I know the true nature of your army. Desire is your army, anger is your army, and ignorance is your army.’

In Indian culture, there is a grass called ‘muñjamāyā.’ Putting this grass in one’s mouth signifies surrender, like raising a white flag. So in the scriptures, there is a scene where he resolves, ‘Do you think I will put muñjamāyā in my mouth? No.’ Thus, it is quite normal for a young practitioner who had been practicing asceticism for six years to have both firm determination and endless arising of mental afflictions.

According to scriptural records, there were three main actions that made it appear Siddhartha had abandoned his ascetic practice. First, he bathed; second, he ate milk porridge; and third, he sat on a bed of kusha grass to practice.

When the Buddha entered his final practice, a cowherd happened to be cutting grass. This grass is similar to pampas grass but much softer. In this region, people use this grass to make rope or mats, similar to how we use straw. Just as we spread straw on the ground to sit on in rural areas, the Buddha spread an armful of dried grass and sat on it to meditate. This grass is called ‘auspicious grass,’ or ‘kusha’ in Indian language. When we travel tomorrow, please try to find some kusha grass. The Buddha didn’t practice sitting on a silk cushion; he made his seat by spreading grass.

Bathing in the stream wasn’t about adorning his body. Eating porridge after collapsing and getting up again follows the same principle as when we consume porridge rather than solid food after a long fast to help our body recover. However, from the perspective of traditional ascetic practice at that time, this clearly appeared to be abandoning asceticism.

After recovering his body and health in this way, the Buddha resumed his practice on the middle path he had discovered and finally attained enlightenment. Without the trial and error experienced here, there would have been no enlightenment. While this is the place where he took the wrong path, it is also where he realized his mistake. Therefore, this can be said to be the place where the ‘Middle Way’ was discovered.

While Bodh Gaya is where he attained enlightenment, it was here that he clearly realized what was wrong through ascetic practice and discovered the third way—the Middle Way—which neither follows nor suppresses desires. Through practicing this Middle Way, he finally attained Nirvana.”

After Sunim’s explanation, the pilgrimage group chanted sutras and meditated.

They then put on their kasayas and offered prostrations toward Jeonjeong-gaksan Mountain.

After offering prostrations, the pilgrimage group visited Yuyeong Cave, where the Buddha is said to have practiced. Sunim returned to Sujata Academy first at 4:20 PM. After dinner, a Dharma assembly was held at 7 PM in Prakbodhi Hall.

First, they watched a video showing students preparing for the pilgrimage. From cleaning the campus and washing dishes to picking up trash at Jeonjeong-gaksan Mountain and installing decorations, there was no corner of the school untouched by the children’s hands.

Next, a video showcasing the 32-year history of Sujata Academy was screened. The children who appeared with youthful faces in interviews in the video had now grown into adults helping with the pilgrimage. The years of growing up alongside Sujata Academy were palpable.

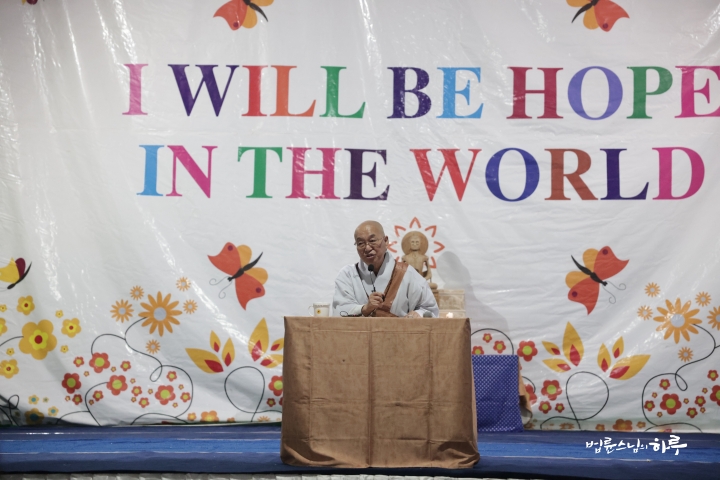

After the video ended, Sunim gave his closing remarks. The pilgrimage group requested his teaching with a chanting request and three prostrations.

“When I first started pilgrimages over 30 years ago, I came here for a preliminary survey. When you come with pilgrims, you can’t properly survey the sites. So before starting the pilgrimage in January, I took time to come in December and carefully examine everything. Back then, we crossed rivers and traversed fields to get here. The path up to Yuyeong Cave wasn’t straight like it is now; it was winding. Along both sides of that path, long lines of beggars sat. There were many people when you went up today too, weren’t there?”

“Yes.”

“Back then, there were far more than now. But nowadays, there are hardly any young children, right? At that time, most of them were young children. So I asked, ‘Is today Sunday?’ They said no. ‘It’s not Sunday, but why are there so many children here? Isn’t there a school here?’ I asked jokingly. But they said there was no school. With so many children, it didn’t make sense that there was no school. I asked as a joke, but there really wasn’t one.

A School Built in a Poor Village

After that conversation, we climbed the mountain, visited Yuyeong Cave, and came back down. We sat under the shade of bamboo trees and talked with the village elders. When I asked if they needed a school with so many children, they looked at me as if to say ‘Is that even a question?’ and said of course they needed one. When I asked why they didn’t ask the government to build a school, they said this was an untouchable village, so no matter how much they asked, it would be useless. I suggested that if they needed a school, we could build one together, but they said they had no money.

As the conversation continued, I asked, ‘How much would it cost to build a school?’ The people discussed among themselves and said about 50,000 rupees would be enough. So I said, ‘I’ll give you 50,000 rupees, try building it.’ However, that money wasn’t even enough for the foundation work. I asked again.

‘By the way, are these children ones I gave birth to, or ones you gave birth to?’

They said they were their own children. So I asked again, ‘If they’re your children, why aren’t you doing anything?’ They said they had no money. I told them that no matter how poor they were, as parents they should do something, and asked if they had land. They said they had land. So I told them to discuss among themselves and donate land for building the school. These were their children and their country, so they should do something too. That’s how ten people each decided to donate 10 Katha. I became the person who received land donations from the poorest people in this village. (laughter)

So this land wasn’t something I selected or designated. The villagers offered what they considered to be the most useless piece of land. But coincidentally, this land happened to be at the entrance to Dungeshwari Cave and right in front of the stupa site. When people visit and see it, they ask, ‘How did you secure such a prime location?’ Korean monks are known for their expertise in feng shui. When they climb up the mountain and look around, they say the feng shui here is excellent. But I didn’t choose it based on any criteria – the villagers gave it to us because they thought it was the most unusable land.

This is how we decided to build the school on the approximately 450 pyeong (about 1,500 square meters) plot at what is now the elementary school entrance, and the villagers said they would build the structure themselves. Now that we had decided to build a school, we needed to raise funds. At that time, I didn’t have any money at all. So I organized pilgrimage tours three times a year. Back then, I never thought of bringing two buses at once. I was worried I wouldn’t be able to provide proper explanations. So I brought one bus at a time, scheduling three separate pilgrimages – early January, late January, and mid-February.

Living Together with the Villagers Through Challenging Times

On one side, we gathered children under the shade of trees to teach them, and after washing them, we changed them into clothes brought from Korea. On the other side, we simultaneously began building the school. I rented a house in the village and lived there with them. When I recently revisited that house, I found they had drawn my face on the wall. As time passes, this might become a legend in this village. (Laughter)

When I heard there was a room available in one house, I went to check it out and found it was where they kept goats. They moved the goats out, and I was to sleep there. But when I watched where they took the goats, they brought them into their own room. When I first arrived, people were living on dirt floors covered with straw, sharing their homes with goats and chickens. I spread fresh straw and laid out my sleeping bag, but after a few days, when I turned the sleeping bag inside out, I found several bugs inside. Thanks to the solid early education I received growing up in the countryside, I managed to adapt somehow. Otherwise, it would have been difficult to endure.

That’s how I lived in that village – working together with the residents, eating together, living together. We were all in the same situation with nothing to lose and nothing to own. Food wasn’t plentiful either. Whenever I tried to eat some scorched rice I had brought, children would always follow me around. I couldn’t even go to the bathroom in peace, so I would pretend to go to the bathroom while looking at the mountains, then quickly pop the scorched rice from my pocket into my mouth and chew hurriedly. That’s how I spent those early days. (Laughter)

A New School Structure Where Learning Begets Learning

This is how the school gradually took shape. Initially, we had about 150 students, and we divided them into two classes. They were all first graders. There was no second grade. But about a year later, when I was spending a summer here, an incident occurred. During morning assembly, children kept collapsing. So we brought a doctor from Bodh Gaya to examine them. The doctor said:

‘For these children, one banana, one glass of milk, and one packet of biscuits would be better than any medicine.’

When I heard what they were saying, it turned out that most of the children were suffering from malnutrition. When I was young, half the children had runny noses and boils on their heads that we called ‘heondee.’ But it was only then that I first learned these were caused by malnutrition. After learning this fact, when I went to North Korea, I found the exact same situation there. ‘Ah, this is malnutrition,’ I could recognize it immediately. So we started a school meal program. After three months, the boils on the children’s heads completely disappeared, and their runny noses stopped. That’s how the meal program began.

But this became the start of another problem. My original plan was to establish one small school at each holy site, because there were so many children begging at each location. However, once we started the meal program, the number of students suddenly increased to 300. So the four classrooms on the first floor couldn’t even have their completion ceremony before we had to immediately start building a second floor. With 300 students, we needed at least six classrooms.

We built the first floor in 1995 and completed the second floor in 1997 with a completion ceremony, so it took three years to finish the entire school. During that time, grades naturally formed from first to sixth grade. Children who had been wandering around heard that ‘there’s a school here that provides meals’ and flocked to us. Suddenly all grades were formed – 6 students in sixth grade, 12 students in fifth grade, and so on.

As a result, it wasn’t just about teaching. The newly arrived children came wearing school uniforms, but the original students didn’t have any, so we had to provide uniforms for them too, as well as shoes. While the school was becoming more like a proper school, it also meant that expenses kept increasing.

About three years later, three male students graduated and went on to middle school, but the three female students were not allowed to leave their homes after graduation and couldn’t attend middle school. Then those children asked me to establish a middle school. Although I grew up in Korea, free education was only available through elementary school. I did attend middle school, but barely managed while working to earn money. So at first, I firmly told them:

‘I’ll only support you through elementary school. Middle school is not possible.’

I refused like that, but the following year, three more female students graduated. Then six female students came to me crying and begging to go to middle school. Around that time, Dr. Ariyaratne from Sri Lanka suggested it would be good to create preschools in each village to care for children. At first, I thought it made no sense to talk about preschools when we didn’t even have enough elementary school teachers. But as his suggestion overlapped with the girls’ situation, a new idea occurred to me. So I made this proposal to the female students:

‘Could you take care of preschool children in the morning? If so, I’ll create a middle school program for you in the afternoon.’

The female students said they could do it. In this culture, it was natural for older sisters to take care of younger siblings anyway. So we established a preschool, and the middle school began with female students caring for children in the morning and attending middle school classes in the afternoon. We created a structure where students teach students.

This idea actually came from my own elementary school experience. When I was in school, our grade had 36 students but often didn’t have a homeroom teacher. Only first and sixth grades had homeroom teachers, and the vice principal was in charge of the rest, but rarely came to class. So I always played the role of teacher for about half the time in my class. (laughs)

Remaining Challenges After Eradicating Illiteracy

The current challenge facing Sujata Academy is whether to establish a high school and an inter-college, which is a pre-university program. The question remains whether the school should be expanded to that level. To do so would require hiring new qualified teachers. Government approval requires securing more than ten teachers with master’s degrees, which is not realistically easy. Hiring qualified teachers means paying standard salaries, which could break the communal character that Sujata Academy has maintained. There’s a risk that instead of being a community school where teachers live together with the children, it could become merely a school that teaches academics. Even if government approval is obtained, accepting those conditions as they are presents a rather ambiguous situation.

The second challenge is the school’s direction. As Indian society as a whole changes and living standards gradually rise, there appear to be two main options. One is to create a vocational school and establish an upper-level school where children can prepare for employment. The other is to go beyond the original goal of eradicating illiteracy and develop into a school that provides higher education, helping children advance into Indian society. Following Buddhist teachings, considerations include whether to pursue fields that help others, such as Buddhist studies or nursing, or to develop into a specialized arts school for the artistically talented children of this region.

The problem is that these children come from low social status and poor family circumstances, making it difficult to receive sponsorship. Apart from jobs like railway civil servants, police officers, soldiers, and teachers, there are almost no options. Passing the exams is difficult, and even if they pass, in Indian society, substantial bribes are required. However, we cannot support them to that extent. So even when children graduate from upper-level schools, other problems arise. While the school clearly played a good role in eradicating illiteracy initially, there’s now a risk of it becoming a place that produces local ‘lumpen.’ They’ve studied but don’t want to do hard labor, yet there are no suitable jobs available. With poor families needing to consume and an increasing number of idle young people, this is a challenge that must be addressed going forward.

Therefore, attracting Korean companies to build factories was also considered. However, the transportation and location were not suitable given the circumstances. Initially, some children were placed in Korean companies in Delhi. But that wasn’t really something for me, a monk, to be doing. Like parents trying to get their children employed, I went from company to company asking for favors and submitting resumes. After sending about ten children, I stopped. While some children settled well because they spoke Korean well and had experience living with Koreans, others couldn’t adapt to city life and returned.

In any case, the eradication of illiteracy has clearly achieved successful results so far. Issues like tuberculosis eradication and infant and maternal mortality have also been resolved to some extent. However, problems such as village development, housing improvement, and income increase have not been properly addressed yet. These are challenges that must be solved step by step going forward. Now JTS stands at an important crossroads, deciding whether it would be better to conclude school operations at this level and hand them over to the government, or to choose another path.

The Dharma assembly concluded at 9:30 PM. Sunim went to the JTS office and exchanged greetings with the resident members of the India lay Sangha and the Indian staff members.

There were also several temporary volunteers who had come to assist with this pilgrimage. Sunim asked each Indian staff member about their current responsibilities.

He then spoke with the medical professionals from Jungto Society who would be responsible for medical care during the pilgrimage, as well as with the leaders of various divisions and local chapters. All activities finally concluded a little after 10 PM.

Tomorrow, the pilgrimage will visit Bodh Gaya, where the Buddha attained enlightenment after completing six years of ascetic practice.