Jul 23, 2025. Baekjung Prayer Opening Ceremony

Hello. Today marks the beginning of the Baekjung Prayer, 49 days before Baekjung Day. In celebration of the Baekjung Prayer opening ceremony, memorial lanterns have been arranged in the front yard of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

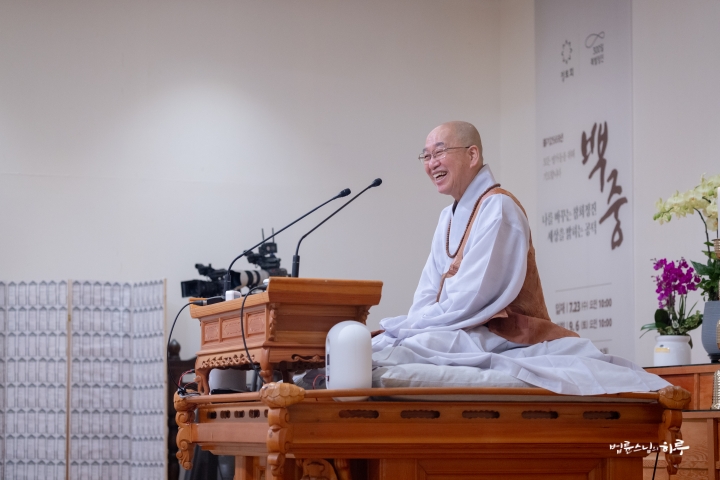

After completing morning practice and meditation, Sunim began the special Dharma assembly for the Baekjung Prayer opening ceremony at 10 a.m. About 120 members of the Sangha gathered in the third-floor Dharma Hall, while approximately 4,000 Jungto Society members joined the live broadcast online.

After reciting the Three Refuges and the Heart Sutra, a video was shown featuring news from Jungto practitioners during the week. This was followed by another video showing last week’s interfaith dialogue on reconciliation and peace with religious leaders from Sri Lanka who were invited to Korea.

▲ Watch Video

When the video ended, enthusiastic applause filled the room. The sight of people working together for reconciliation and peace across religious boundaries, despite the challenging circumstances of civil war and division, deeply moved everyone present.

Everyone then requested the opening Dharma talk with three prostrations. Sunim began the Dharma talk by offering heartfelt condolences to citizens affected by the recent heat waves and heavy rains.

“Two weeks ago, many suffered from extreme heat, and last week, natural disasters occurred throughout the country due to heavy rainfall. Farmland and homes were flooded, and landslides occurred, tragically resulting in many deaths. I pray for the repose of those who lost their lives and extend my deepest condolences to their families. Additionally, for the swift recovery of damaged farmland and homes, not only the government but each of us as citizens should contribute whatever small help we can offer.

What Small Help Can We Share for Those Affected by Heat Waves and Heavy Rains?

JTS is currently surveying the affected areas. In Gapyeong, Gyeonggi Province, the damage is relatively limited, making it possible for local governments to provide material support. However, field investigations revealed that residents cannot use their household items, and drinking water is most urgently needed. Therefore, water supply support was decided as the first priority. Surveys will continue in South Chungcheong Province and Sancheong in South Gyeongsang Province to identify what support is needed for disaster victims and provide specific assistance. Of course, Korea is a relatively prosperous country, and local governments are actively conducting relief activities for residents, creating conditions where individual citizens don’t necessarily need to take direct action. Nevertheless, if we can share even a small part of the victims’ suffering, that compassion will become a small but precious force in alleviating their deep sorrow.

Dialogue for Peace with Sri Lankan Religious Leaders

Last week, The Peace Foundation invited Sri Lankan religious groups to attend the International Reconciliation Conference and engage in dialogue. We heard their stories about how religious leaders have worked for peace amid ethnic and religious conflicts in Sri Lanka, and we shared how Korea’s religious communities have cooperated to ease tensions between North and South Korea and alleviate the suffering of North Korean people. Afterward, we visited the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the site of division. Although it appears peaceful on the surface, we were reminded once again that the Korean Peninsula remains a region where tensions run so high that war could break out at any moment.

Just around this time last year, we were deeply concerned about the possibility of war. Fortunately, through the people’s prayers and heaven’s help, it seems we have overcome that crisis to some extent. While seeds of conflict remain, we have at least moved away from the imminent threat of war. Since the new government took office, hostile measures between North and South Korea have been withdrawn one by one, and North Korea has responded positively to some extent, significantly easing tensions between the two Koreas. Moving forward, I believe our important task is to take another step forward and further enhance exchanges and cooperation between North and South Korea.”

Then, Sunim gave a one-hour Dharma talk on the meaning of the Baekjung Prayer. He first explained the origin of Baekjung and its connection to Buddhism.

“If Memorial Day is a national day to honor the patriots who sacrificed themselves for the development and independence of our country, Baekjung is a day in Buddhism to honor our ancestors who gave birth to us and raised us. It falls on the 15th day of the 7th lunar month. While some hold events to honor ancestors for just this one day, traditionally it is not observed for only one day but involves seven prayer sessions called the 49-day memorial service. Today marks the opening day of the Baekjung Prayer. Starting today, we will offer prayers seven times and conclude on the final day.

The Origin of Baekjung and Its Connection to Buddhism

The reason we observe the 15th day of the 7th lunar month as a day to honor our ancestors is because this custom originated from Indian culture. Even before the Buddha appeared, Indians had a folk tradition of going to the Ganges River on the Full Moon Day of the fifth month in the Indian calendar to scatter food and honor their ancestors. However, the Buddha did not involve himself in such traditional cultural or folk events. When asked, ‘How should we conduct funerals?’ he replied, ‘Let people do as they have been doing. Whether they bury or cremate, let them follow their own customs.’ Honoring ancestors is also a custom. The Buddha did not say ‘do it’ or ‘don’t do it,’ but simply said, ‘Let them do as they have been doing.’

So initially, it was a day when Indians who were not practitioners honored their ancestors according to their customs. Although Buddhism first spread among a small group of monastic practitioners, as the number of lay practitioners increased and the religion gradually reached the general public, people continued to observe the folk traditions they had long practiced. Just as Koreans pray during Jeongcho (New Year) or the winter solstice, Indians also held New Year celebrations and ancestor honoring ceremonies. Although it was rooted in folk traditions, as Buddhism spread widely and the majority of the population became Buddhists, folk traditions simultaneously became Buddhist events.

For example, Chilseok(the seventh day of the seventh lunar month) is not a Buddhist event but a folk tradition. However, during the Silla and Goryeo dynasties, when the majority of the population were Buddhists, folk traditions naturally became Buddhist events, and folk traditions became national events. Buddha’s Birthday on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month was originally a Buddhist event, but it became a national holiday as the entire population embraced Buddhism. Chilseok was originally a folk tradition but came to be accepted as a Buddhist event. This means that initially, when the Sangha was not involved and believers only observed Baekjung as a folk tradition, there were no major issues. However, as this event gradually became established as a Buddhist event, the question arose: ‘Shouldn’t this be connected to the Buddha’s teachings as well?’

Additionally, while leaving home to become a monastic is a common cultural practice in India, from the general perspective of honoring ancestors, leaving home could appear to be unfilial. Parents lovingly gave birth to and raised their children, only to have them leave home. Because of this, Buddhism needed to provide an interpretation: ‘Leaving home is by no means unfilial. True filial piety is not just preparing offerings for parents, but praying to eliminate the sins parents have committed and help them go to a good place.’

India has many diverse pujas, or folk traditions. Among these many traditions, only Baekjung has come to Korea through Buddhism and taken root as both a folk tradition and a Buddhist event. This can be attributed to our people’s traditionally strong culture of honoring ancestors. Baekjung-jeol or Ullambana explains how this custom of honoring ancestors was combined with Buddhism.”

Sunim then shared the story of Venerable Moggallana, which is the origin of the Ullambana (Baekjung). To save his mother from hell and the realm of hungry ghosts, Venerable Moggallana followed the Buddha’s teachings and made offerings to 500 practitioners on the last day of the retreat. Through this merit, he was finally able to save his mother. As Sunim told this ancient story, the tale from the scriptures unfolded like a movie. Sunim explained the meaning contained in this story.

“We need to think about what Venerable Moggallana’s story symbolizes. While Baekjung is a folk tradition, from the perspective of Buddhist practice, it contains two important meanings. First, the karmic consequences of our actions cannot be avoided. To save someone, we must examine their karmic consequences and create merit to repay their debts. Second, one must attain enlightenment oneself. While others can help by accumulating merit to enable rebirth from hell to the realm of hungry ghosts, fundamentally, one must attain enlightenment oneself to escape suffering. That’s why the ceremony for the deceased contains both ‘accumulating merit’ and ‘the spirit’s own enlightenment.'”

How to Right an Upside-Down Life

In the story, Venerable Moggallana’s mother pursued only immediate profit. She thought making lots of money through business was more important and skillful. However, she ultimately fell into hell. Despite working hard to be reborn in heaven, she ended up in hell. This kind of upside-down life is called inverted delusion. The word Ullambana comes from the Sanskrit word ‘ullambana,’ which means ‘hanging upside down.’ Therefore, the Ullambana ceremony means ‘righting what is upside down.’

We can easily see examples of ‘inversion’ in our daily lives. What parents do for their children’s sake sometimes causes harm instead. The most effective way to right what is upside down is to accumulate merit by giving to the poor. In the Ullambana (Uran-bun-jae in Korean), ‘jae (齋)’ means ‘to give.’ In other words, accumulating merit is the path to righting an upside-down life.

The Baekjung Prayer originated from Indian tradition but was integrated with the Buddha’s teachings as it entered Buddhism. It evolved beyond being merely a ceremony for deceased spirits to mean that giving to the hungry is merit that lessens the sins of the deceased. Holding memorial services on Baekjung Day is based on traditional memorial rites, while sharing offerings with the poor originates from Buddhist ceremonies. Today’s Baekjung ceremony combines these two elements.

That’s why at Jungto Society, we keep the memorial ceremony simple and use your offerings for humanitarian aid to save lives. For example, we provide food to hungry people in North Korea, children in India, and the hungry in developing countries. We also provide water to the thirsty, medicine to the sick, clothes to the naked, and build homes for the homeless through humanitarian aid activities. This is the concept of ‘releasing life.’ While releasing fish is also releasing life, saving human lives is the greatest merit of releasing life. This sharing aligns with the Buddha’s final teaching: ‘Giving to the hungry, sick, poor and lonely, and those who practice purely has the same merit as making offerings to the Buddha.’

Baekjung, a Day of Gratitude for Both Ancestors and All Beings

Interpreting Baekjung in modern terms reveals two meanings. First, it’s a day to honor the spirit of our ancestors—a day to be grateful for our ancestors who made today’s existence possible. Second, it’s a day to repay the kindness of all beings. The fact that I’m living well today isn’t because I’m exceptional alone, but because someone made clothes, someone farmed, and someone worked silently. We must recognize that today’s life is possible thanks to countless invisible hands. There are many poor people in the world who take on such labor. Baekjung is also a day for them. In the past, Baekjung was ‘Servants’ Day’ or ‘Workers’ Day.’ On this day alone, servants could rest for a day. In that sense, it’s like today’s Labor Day. While modern Labor Day came from the West, if we were to create our own traditional Labor Day, Baekjung would be most appropriate.

If we reconsider this meaning, Baekjung should not simply be a day for performing ancestral rites. It should be a day to look after neighbors in need, for employers to give their employees a day off, and even to provide good feed for working oxen. This day should be remembered as a time when those who suffer can find temporary relief from their pain. Rather than adopting commercialized Western holidays like Pepero Day or Valentine’s Day, wouldn’t it be better to commemorate traditions that revive our unique spirit and values? For this reason, although Baekjung is not directly related to the Buddha’s teachings, Jungto Society believes we can bring its meaning to life through the Buddha’s Dharma and revive it with contemporary significance. That’s why we observe Baekjung Prayer along with Jeongcho Prayer and Winter Solstice Prayer.

In our tradition, we have a culture of wearing white clothes when someone passes away. That’s why we light white lanterns on Baekjung Day. I hope this day can be like Memorial Day – a time to express gratitude for the grace of our deceased ancestors, to pray and give offerings for those who suffer, and to show consideration so they can rest for at least one day. By carrying on this good tradition, we will hold Baekjung Prayer together after our Wednesday Dharma Assembly from now on.”

After the opening Dharma talk ended, the first Baekjung Prayer ceremony began immediately. The seven ceremonies will be held over the next 49 days.

While the Baekjung Prayer at the Jungto Social and Cultural Center was being broadcast live, members of the Sangha watched the live stream from their own rooms, each placing a simple cup of tea as an offering and participating in the Baekjung Prayer together. Everyone recalled their departed loved ones in their hearts and chanted the solemn Buddhist hymns with sincere devotion before concluding the online Baekjung Prayer.

Sunim had a meal with National Assembly member Lee So-young, who came to visit, and they engaged in an in-depth conversation about various issues in Korean society and peace on the Korean Peninsula.

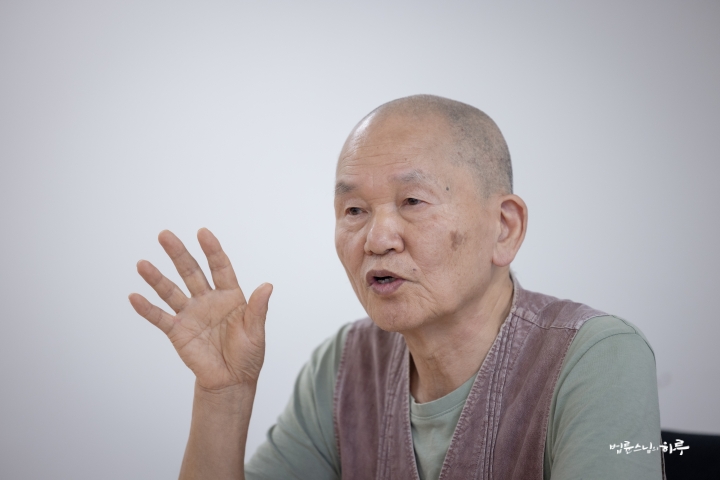

From 1 PM, Sunim attended a seminar with research fellows. Today’s session featured a presentation by Mr. Choi Han-sil on the topic “The Life of Our People and the Korean Language,” followed by a discussion.

Mr. Choi Han-sil has long been dedicated to awakening people to the disorder in the Korean language, reviving dying Korean words, simplifying difficult Chinese-character words into easy Korean, and explaining Korean words using Korean itself. Since his youth, he has been committed to ensuring that working people become the masters of the nation and to uniting the divided Korean people.

Mr. Choi Han-sil emphasized that if we don’t preserve the Korean language, our senses and ways of thinking will be distorted by foreign words, which could lead to changes in and even the disappearance of our nation’s history, identity, and spirit. He shared various examples over the course of two hours.

After Mr. Choi Han-sil’s lecture ended, participants showed deep interest in reviving the Korean language through various questions. A flood of questions poured in.

“In an era overflowing with multiple languages like now, is it realistically possible to revive the Korean language?”

“When you look at Korean dictionaries, they’re full of foreign words and Japanese expressions. How can we revive Korean in such an environment?”

“Why is ‘language’ so important? Isn’t it enough to just think correctly?”

“Isn’t there a danger that such activities might lead to nationalism or exclusivity?”

Mr. Choi emphasized the importance of language transmission between generations and suggested practical directions with specific examples.

“Even if it’s difficult, it’s something we must do, and to go far, we must go together. We must pass on our language to the next generation, even if just a little. So we need to change our words one by one. Use ‘hope’ instead of ‘expect,’ ‘happen’ instead of ‘occur.’ When language changes, thoughts change. When thoughts change, life changes, and the country changes too. Preserving our language doesn’t mean rejecting other languages, but rather not forgetting our roots.”

After listening to the presentation and discussion for three hours, Sunim shared his final thoughts along with the dilemma of the Korean language revival movement.

“What struck me is that pure Korean words are immediately understandable, but Japanese-style Chinese character words pronounced in Korean are difficult. For example, the word ‘sonnim’ (guest) is immediately understood, but the word ‘gogaek’ (customer) is difficult to understand. ‘Gil’ (path) is easily understood, but ‘doro’ (road) is not. I’m talking about when applied to our generation. Because when I was young, my parents didn’t go to school, so they used only pure Korean. Just as people from Jeju Island learn the Jeju dialect at home, I naturally learned pure Korean growing up.

The Dilemma of Korean Language Education in an Era Where ‘Customer’ Is More Familiar Than ‘Guest’

However, when I entered school, I had to learn from textbooks centered on Chinese-character words, and except for particles and verbs, I had to learn most words anew. Later, as the generation that graduated from high school or university became parents, they naturally used the Chinese-character words they learned in school with their children rather than the pure Korean they heard in childhood. As generations changed like this, words like ‘doro’ (road) and ‘gogaek’ (customer) became established as everyday language instead of ‘gil’ (path) and ‘sonnim’ (guest). But children these days grow up hearing words like ‘doro’ and ‘gogaek’ at home, so they don’t know what ‘gil’ and ‘sonnim’ mean. In this situation, if we say ‘pure Korean is easier,’ it might actually feel more difficult to the current generation.

Ultimately, the premise that ‘pure Korean is easy and Chinese-character words are difficult’ works differently depending on the generation, so this aspect seems to need more careful examination. Even for our generation, while ‘gil’ is easier than ‘doro,’ ‘san’ (mountain) is much more familiar than ‘moe’ (mountain in pure Korean), isn’t it? This shows that even we have become more accustomed to Chinese-character words than pure Korean. Moreover, current students are a generation that has hardly been exposed to pure Korean. Yet if we start talking with the assumption that these children know pure Korean, it might be different from reality.

Why Did We Come to Use Japanese-Style Chinese Characters Instead of Our Native Korean Words?

So why did we stop using our native Korean words? I have also thought about the causes of this. Until the Japanese colonial period, we naturally used our native language in daily life. This was because more than 80 percent of the population did not know Chinese characters at that time. Only a few government officials, Confucian scholars, and Buddhist monks used Chinese characters, and Chinese was rarely used in everyday language. Chinese characters were only used in writings for specific specialized fields. So no matter how long the history of using Chinese characters was, it only influenced a small intellectual class and did not have a significant impact on the language of the entire population. However, the situation changed during the Japanese colonial period. As part of colonial rule, Japan established elementary schools and taught Japanese through their own language textbooks. Japan originally had pure Japanese words, but when Western culture came in, while they sometimes adopted foreign pronunciations directly like “bakesu,” in most cases they created new words by combining Chinese characters, such as “peace,” “chair,” and “desk.”

These words created by Japan were Chinese character words, but they were different from Chinese expressions. Until Western culture arrived, Korea, Japan, and China all commonly used Chinese-style expressions. However, as Japan was the first to accept Western culture and created new words, Korea came to encounter these words through Japan. Later, China also adopted these words. This is how Japanese-style Chinese character words like “freedom,” “equality,” “peace,” and “compassion” came to be, and we still use them today.

However, during the Japanese colonial period, less than 20 percent of the population attended elementary school. Therefore, the Japanese language had a greater influence on intellectuals than on the general population. While Chinese characters were limited to the yangban class, Japanese had a broader reach, though it still did not affect the entire population. However, concepts or words that did not exist in Korean had to be adopted directly from Japanese. For example, as new tools like “gonggu” (tools) were introduced, just as we use “computer” directly from English, we had no choice but to use Japanese words as they were. This is why foreign words and Japanese expressions have not easily disappeared and remain to this day.

After liberation, we stopped Japanese language education and switched to Korean language education. However, lacking experience in modern education, we had no choice but to use textbooks from the Japanese colonial period. Japan withdrew, but the content in the textbooks remained largely unchanged. Only the pronunciation changed from Japanese to Korean, while the content and terminology mostly remained the same. As compulsory education was later implemented for all children, the entire population came to study using the language in these textbooks. While children learned “sonnim” (guest) and “gil” (road) at home, they learned “gogaek” (customer) and “doro” (road) at school. Over time, the language used at home was replaced by the language used at school. This is how Japanese-style Chinese character words became the mainstream language used by the majority of the population today.

Concerns About Replacing All Words with Pure Korean

I think it would be good to improve by considering these aspects. We need to revive our language within a reasonable scope, such as using ‘gomapseumnida’ instead of ‘gamsahamnida’ (both mean ‘thank you’), ‘sonnim’ instead of ‘gogaek’ (both mean ‘customer’), and ‘gil’ instead of ‘doro’ (both mean ‘road’). I believe we absolutely need a movement to restore the words we originally used back to our native language. However, replacing every single word with pure Korean is a different matter altogether. For example, the word ‘jayu’ (freedom) is a new term that we rarely used in the past. While there might be ways to express such words in pure Korean, we need to consider whether it’s necessary to find and use archaic words. If we try to change even words for concepts we never experienced in our history, we fall into a dilemma of deciding where to draw the line. I would like to think about this together.

I agree with restoring Korean words that were commonly used in daily life but have been pushed out by Chinese characters or foreign words. However, to replace every word, we would need to create new words. This would ultimately require comprehensive re-education for all 50 million citizens. We have mountains of work ahead of us – is it really possible to gain public consensus for such a change? I want to examine this from a practical perspective.

You mentioned that ‘AI (artificial intelligence)’ should be changed to ‘beontdogi,’ but what’s the difference between ‘AI’ and ‘beontdogi’ that makes it necessary to change? ‘Beontdogi’ isn’t even a word that existed in our original language. The logic that newly created words are pure Korean while ‘AI’ is not seems difficult to defend against criticism of being overly nationalistic. Of course, changing difficult foreign words to easy Korean words is good. However, I think the argument that all foreign words must be newly created in Korean would be difficult for the public to accept in reality. I’m concerned this might prevent the movement from spreading socially.

Wouldn’t it be better to organize the content of currently used terms well so that the public, especially the younger generation, can accept them more easily? I also think attempts to change numerous words we use to pure Korean are meaningful. Even if it’s not something the entire nation participates in, I believe it’s necessary at the level of academic research or partial practice. I think translating the constitution into pure Korean or Jungto Society’s attempts at refined Korean expressions are definitely meaningful. However, the direction of changing all words to pure Korean seems to need reconsideration in several aspects. First, I wonder about its efficiency; second, whether it can gain public sympathy; and third, whether it’s absolutely necessary. I think we need to consider these aspects further.

I believe that words we used in daily life before learning them in school, but which were then phased out through formal education, make up about 70 percent of the terms we use today. For instance, it’s entirely possible to go back to using words like ‘gil’ (road) and ‘sonnim’ (guest), which we naturally used as children, instead of Word of Chinese origin used in Korean like ‘doro’ (road) and ‘gogaek’ (customer). While creating new pure Korean words to replace Word of Chinese origin used in Korean is difficult, reviving words we used before formal schooling is an achievable effort. Even if we don’t go so far as to insist on using only Korean words and forcing the creation of new ones that never existed, I think we should revive and use words that we used in daily life but were pushed aside through school education. Wouldn’t that alone achieve more than half the desired effect? As for the opinion that all words must be thoroughly changed to pure Korean, I think more discussion is needed.”

Just as Teacher Choi Han-sil continues his research on the Korean language and carries on the movement to revive Korean words, the participants agreed to find things each person could do and put in more sincere effort. The seminar concluded with enthusiastic applause.

Following this, from 4 PM, Sunim continued with a meeting with the planning committee members of The Peace Foundation. By the time the meeting ended, the sun had set.

In the evening, Sunim wrapped up the day’s activities after proofreading manuscripts and attending to various other tasks.

Tomorrow, Sunim will have an early morning breakfast meeting with North Korea experts, followed by discussions with the secretariat about the schedule for the second half of the year. In the afternoon, he will travel to Mungyeong Jungto Retreat Center to prepare for the Meditation Retreat starting the day after tomorrow.