Jul 15, 2025 – International Association for Reconciliation, Asian Interfaith Dialogue for Reconciliation and Peace

Hello. Today is the day of the International Association for Reconciliation conference on the theme of “Asian Interfaith Dialogue for Reconciliation and Peace.”

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim departed from the Jungto Social and Cultural Center with Sri Lankan religious leaders to attend the International Association for Reconciliation conference at Seoul National University.

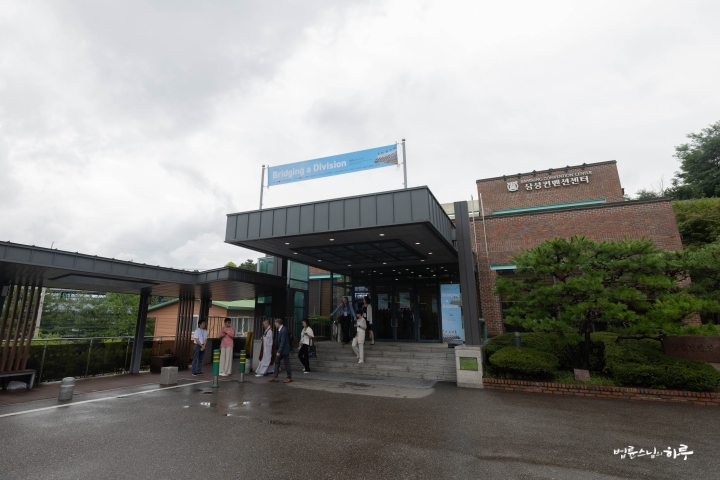

At 9:30 AM, Sunim arrived at the Hoam Faculty House at Seoul National University where the event was being held. The rain that had been falling since yesterday had taken the edge off the sweltering heat. Having arrived at the venue a bit early, participants read through their materials and prepared for the discussion.

Professor Nam Ki-jeong, Director of the Institute for Japanese Studies at Seoul National University who organized this International Association for Reconciliation conference, began the conference at 10 AM with opening remarks.

“This event is the first international conference in Korea on the theme of ‘reconciliation.’ I believe this conference will serve as a reference point when thinking about ‘reconciliation’ in Korea going forward. When I was considering whom to invite as panelists, the first people who came to mind were Venerable Pomnyun Sunim, whom I deeply respect, and the activities of The Peace Foundation’s interfaith gathering. We have excellent panelists here today who are well-suited to our dialogue theme. I would especially like to express my gratitude to the religious leaders who have come from far-away Sri Lanka.”

Following this, Reverend Park Jong-hwa gave welcoming remarks.

“Today we want to hear about how Sri Lanka has reconciled its conflicts. And we would like to share with you how we are addressing the issues of South-South conflict and North-South conflict. The theme of our dialogue is to work for peace while becoming champions of reconciliation. I hope this will be a meaningful gathering.”

After brief participant introductions, Reverend Anura gave the first keynote presentation. Reverend Anura provided a detailed introduction to the 30-year journey of ‘Dharmashakthi’ for interfaith harmony in Sri Lanka. It was a moving example of practical action that overcame the wounds of Sri Lanka’s civil war and created genuine peace in the name of religion.

“In 1993, not long after the Sri Lankan civil war began, progressive religious leaders from Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity joined hands to establish an interfaith council called ‘Dharmashakthi.’ Its purpose was singular: to achieve true harmony even amid extreme division.

Creating Peace Beyond Religious Differences

Political leaders, consumed by endless greed for political power, deliberately fostered conflict and division, and encouraged extremism. As a result, society fell into a vicious cycle of distrust and violence. Sri Lanka suffered from extreme distrust between religions and ethnic groups during 30 years of civil war. Dharmashakthi has been bringing about change in these wounded places through religious healing and social solidarity. To put interfaith dialogue into practical action, Dharmashakthi practices 10 basic rules. Among them, the core principles are as follows:

‘We avoid generalizations like “everyone is like that” and instead say “I believe” or “I feel this way.”‘

The first is the principle of first-person speech. This way of dialogue becomes a foundation for understanding each other based on individual beliefs and experiences, listening without judging others. In addition to this, we practiced various principles such as not interrupting, prohibiting unsolicited advice, and ensuring equal speaking rights regardless of religion.

Dharmashakthi did not remain at the level of mere dialogue. There are cases where we actually led to changes in government policy. When the government ordered the forced cremation of those who died from COVID-19, the Muslim community strongly opposed this as they considered burial a religious obligation. We courageously supported this right to burial, and eventually the policy was changed to respect religious practices. In this way, Dharmashakthi actively participates in political and social responses to protect religious beliefs.

To prevent conflicts from recurring, Dharmashakthi educates about interfaith understanding and cooperation through the high school program ‘Ekamuthu Lanka.’ Regardless of differences in beliefs, we share the commonality of being human. We help young people from various religions and ethnicities gather in one place to understand each other and grow as future peace leaders.

Dharmashakthi also conducts ‘pastoral diplomacy,’ directly meeting with conflicting parties to mediate based on the moral authority of religious leaders. Our religious identity opened doors that were closed to politicians.

We are different from each other, but we must create a sacred ground where these differences can coexist and flourish. Going forward, Dharmashakthi plans to cultivate young religious leaders, spread peace messages through digital platforms, and continue responding to extremism and political division. Interfaith cooperation is not an ideal but a realistic path that can be achieved through practice, courage, and patience.”

Through Reverend Anura’s presentation, we could see how Dharmashakthi has established such delicate standards and attitudes for sincere dialogue and mutual respect, and has carried out various practices.

Next, Venerable Pomnyun Sunim, President of The Peace Foundation, gave a keynote presentation on the theme of “Religious Leaders’ Efforts for North-South Reconciliation and Peace on the Korean Peninsula and in Asia.”

“In Korea too, the conflict between North and South remains deep and acute. Even within South Korea, there are endless conflicts and debates about how to resolve North-South tensions and how to address the North Korean issue. To help solve these problems even a little, various Korean religious leaders have gathered and worked together for the past 27 years. Today, I would like to briefly introduce the steps Korean religious leaders have taken for reconciliation and peace.

How Can We Heal the Wounds Caused by Conflict?

When people live together, conflict is unavoidable. When conflicts intensify, they become disputes and can even escalate into wars. Looking at the root causes of such conflicts, it ultimately comes from a lack of acknowledgment and respect for our differences. Also, misunderstandings arise from not understanding each other, and misunderstandings grow into conflicts. Therefore, if we recognize our differences and understand that ‘the other person could be that way,’ we can find clues to resolve conflicts and disputes.

Conflicts leave deep wounds in people’s hearts. So how can we heal these wounds? Based on mutual understanding, those who have caused hurt must be able to sincerely apologize, and those who have been hurt also need an attitude of forgiveness. However, in reality, those identified as perpetrators often don’t feel sufficient responsibility, saying ‘What did I do that was so wrong?’ On the other hand, those who have been hurt receive their wounds even more sensitively, placing all blame on the other party and demanding apologies. When such attitudes are repeated, relationships cannot be easily restored.

Religious people, regardless of their different religions, respect and understand human relationships, and view problems based on love, compassion, and forgiveness. Religious differences only appear in differences of rituals and culture, but the essential teachings are not different. Therefore, I believe that if people from different religions gather and practice the original teachings together, we can generate the power to solve problems.

There Is No Just War, No Good War.

Yet today, the world is not moving in the direction we hope for. Looking back at just the past few years, the war caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues even now, and Israel’s bombing of Gaza has led to inhumane and inhumane acts that are closer to massacre than war. Some voices defending Israel’s actions in the name of national security are actually undermining the morality that the liberal world has upheld. Even looking at the Iran issue, airstrikes and bombings were carried out without prior notification to the other party during nuclear negotiation talks. Such preemptive strikes violate international law. However, those who wage war always claim their actions are justified. This perspective, which believes even bombing and terrorism are justified, is further increasing the damage.

Everyone claims to wage a just war, but objectively speaking, there is no just war, no good war. War takes lives, destroys property, and leaves only suffering and wounds for countless people. Beyond the direct damage of war, the lives of refugees who have left their homes and countries due to war are indescribably painful. When touring war-damaged areas, one desperately realizes that war must be prevented for any reason. The Korean Peninsula where we live may seem peaceful now, but the danger of war that could bring mass casualties lurks at any time. We experienced countless sacrifices from the Korean War 75 years ago and have painful memories of our entire country being reduced to ruins. Since we are still exposed to the danger of new wars even before that war has ended, the most important task for us is not what religion we believe in, but how to prevent this war and preserve peace.

Reaching Out to the Starving, Breaking Down the Barriers Between North and South

It is never easy for religious leaders to unite and accomplish such work. However, in Korea, there was a catalyst that enabled different religions to join forces. In the mid-1990s, countless people lost their lives due to severe famine in North Korea. Millions died in this tragedy. Faced with such suffering, we could no longer hold onto ideologies like past wars or hostile relationships. As people were starving to death before our eyes, we as religious leaders could not turn away from their pain. The urgency to act together became a major catalyst for breaking down the thick barriers between North and South.

Due to the hostile relationship between North and South, anyone who tried to help or understand North Korea faced severe criticism within South Korean society. Nevertheless, religious leaders courageously began to open the floodgates of humanitarian aid to North Korea. At that time, while North Korea suffered from severe food shortages with many people starving, South Korea had an oversupply of potatoes that would have to be discarded. We purchased those potatoes to reduce losses for South Korean farmers and distributed them to starving North Korean residents. This movement, which not only helped North Korea but also addressed the difficulties of South Korean residents, became the first breakthrough in penetrating the thick barriers between North and South.

Buddhists, Christians, and Catholics joined forces to launch the “One Million Signature Campaign” to prevent mass starvation in North Korea. Despite the lingering hostility toward North Korea in the hearts of the people, this campaign became a turning point in creating consensus that humanitarian aid was necessary. Subsequently, many religious leaders visited North Korea directly, and as inter-Korean summits were held, exchanges and cooperation became more active.

Religious Groups That Have Opened Channels Whenever Inter-Korean Relations Were Blocked

Religious leaders have played a role in opening channels whenever inter-Korean relations were blocked, and once channels were opened, subsequent exchanges became something anyone could participate in. However, when inter-Korean relations became strained again in 2008 due to a change in government, we once again launched the “One Million Signature Campaign” calling for humanitarian aid to North Korea. Despite government opposition, we persisted in our persuasion and eventually visited Kaesong directly to deliver food. More important than the quantity of food was the fact that we had reopened blocked channels. This opportunity allowed the door for humanitarian aid to North Korea to open once again.

While humanitarian aid to North Korea and activating inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation were important, it was equally important to resolve the sharp internal conflicts within South Korea between those who supported and opposed such efforts. To resolve this conflict, religious leaders took the lead in announcing the “National Unity Declaration” together with social elders. This declaration was an agreement between the progressive camp that supported exchanges with North Korea and the conservative camp that opposed them, with the intention of continuing exchanges and cooperation steadily without going too far ahead or stopping altogether. Even if it meant taking one step at a time instead of two, the message was not to stop exchanges and cooperation. This declaration was adopted at the National Assembly plenary session and is recognized as a movement created by civil society as a whole, going beyond simple solidarity activities among religious groups.

In particular, in 2016, religious leaders united to make a Declaration of National Unity. Its roots go back over 100 years to the Japanese colonial period. During the March 1st Independence Movement in 1919, 33 religious leaders from three religious organizations drafted the Declaration of Independence and proclaimed Korea’s independence to the world. Based on this, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established, which can be said to be the foundation of today’s Republic of Korea. We religious leaders inherited this spirit and made the Declaration of National Unity to serve as a foundation for reconciliation and cooperation between North and South Korea.

Nevertheless, in 2017, inter-Korean relations deteriorated to their worst point, escalating to the brink of war during the early days of President Trump’s administration. Even then, religious leaders took the lead in opposing war, making declarations on the state of affairs and a Ten Thousand People Peace Declaration, and continuing peace marches in Gwanghwamun. I believe these efforts created the opportunity for the inter-Korean summit and the North Korea-US summit to be held in 2018. In this way, we religious leaders have continued to play a small role whenever inter-Korean relations have been difficult.

In 2024, inter-Korean relations have become so tense that war could break out at any time. We gathered again at Jangsu Jukrimjeongsa Temple on June 13th and made a Ten Thousand People Peace Declaration. Although these religious aspirations did not directly bring about major changes in inter-Korean relations, I believe they served as a starting point for lowering the risk of war on the Korean Peninsula.

Our religious leaders’ gathering considers three values to be most important. First, under no circumstances should there be another war on the Korean Peninsula. Second, humanitarian aid must continue under any circumstances to share the suffering and pain of North Korean residents. Third, we must ease the confrontation and conflict within South Korea caused by inter-Korean relations issues and achieve national unity by finding points of agreement through dialogue.

Beyond Religion, Beyond Borders, Steps of Solidarity for Asia

Along with activities to improve inter-Korean relations, we religious leaders are taking responsibility not only for issues within Korea but also for current affairs in the Asian region. The Asian region experiences frequent conflicts due to its religious and ethnic diversity. Religious gatherings in Korea are primarily led by Christianity, including Catholics and Protestants, and Buddhism. While there aren’t many Muslims in Korea, many of the struggling regions in Asia are Muslim areas. Therefore, we believe we should provide help without discrimination wherever there are suffering people, regardless of religion or nationality.

For example, the Mindanao region of the Philippines has a Christian majority, but minority Muslims and indigenous peoples also live there together. Due to conflicts between government forces and rebel organizations like the MILF (Moro Islamic Liberation Front) in Muslim areas and the NPA (New People’s Army) in indigenous areas, many children have been unable to receive education. So we built schools in indigenous and Muslim conflict areas to support children in studying together. Over the past 20 years, we have made a small contribution to bringing peace to Mindanao by establishing over 70 schools. Additionally, India’s Dalit class often cannot receive education due to caste discrimination as untouchables. So we established schools that anyone can attend regardless of class or gender, enabling them to receive basic education. We have also continued local medical volunteer work and village development.

Natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes are frequent in Asia. In 2023, schools were restored in northern Syria, which had been destroyed by the Turkey-Syria earthquake, enabling 4,000 students to study. In flood-affected areas of Pakistan, hundreds of houses were built for displaced people. Support activities were also carried out in war-torn regions of Afghanistan, and a girls’ dormitory was built in Cambodia to promote women’s education.

Korea also experienced difficulties in the past, but has now become economically prosperous. Rather than boasting about our development, I believe we should remember our difficult times and continue activities to help our neighbors who are suffering.

Reconciliation is not a declaration but a practice we do together.

While we still face many difficulties in inter-Korean relations, today’s presentation by the Sri Lankan religious community gave us significant insights. Sri Lanka, in particular, experiences not only ethnic conflicts but also religious conflicts. I was deeply moved hearing how religious leaders have established and implemented strategies for peace with courage and wisdom. As peace between North and South Korea has not yet been fully realized, we will continue to work persistently for peace on the Korean Peninsula and the resolution of national conflicts within South Korea.

I believe reconciliation cannot be achieved simply through declarations or research. To achieve reconciliation, we must empathize with each other’s pain and work together to share and resolve that pain. Only then can the knots in our hearts gradually loosen, making true reconciliation possible. Therefore, we religious practitioners aim to go beyond merely researching or declaring peace and reconciliation, and instead continue making small contributions to alleviating the wounds and suffering in people’s hearts through activities that share pain together in the field.”

All participants expressed their strong support with loud applause for the activities of this religious gathering that has worked alongside suffering neighbors and achieved peace through action. The message that action—empathizing with and sharing each other’s pain—is more important than declarations left a profound impression.

Following this, a discussion session was held. Former Cheondogyo Leader Park Nam-soo reflected on the work the religious gathering has done and added a few words.

“Our gathering is not called ‘for National Integration’ but ‘Religious Gathering for National Reconciliation and Peace.’ Although we have been active for 27 years, we haven’t achieved satisfactory results. However, I believe we have sufficiently fulfilled our role in presenting a milestone for the direction religious people should take, and we continue to participate with joyful hearts even now.”

Venerable Asaji shared more specific examples of Dharma Shakthi’s activities.

“In 1996, there was no integrated organization for interfaith harmony in Sri Lanka. A culture of suspicion was deeply rooted in society, where people would become suspicious just by seeing people of different religions together. I started Dharma Shakthi activities to break down these social stereotypes. I realized what seemed like a ‘miracle’ of breaking down religious boundaries by providing Buddhist temples as prayer spaces for Muslims. This unprecedented activity led to joint festivals being held in churches, temples, and mosques over the following five years. Recently, we have been wisely reducing the seeds of conflict by arranging reconciliation declarations and opportunities for inclusive speeches by leaders for Tamil diaspora who have migrated to Nepal.”

Venerable Asaji also emphasized that for interfaith solidarity to become sustainable activities rather than just conferences, it must be supported by trust, courage, and action.

Just as the conversation was deepening, it was time to conclude. It was regrettable that the discussion time was so short. It was decided to continue the insufficient dialogue in the afternoon at the Jungto Social and Cultural Center, and the conference was concluded.

After taking a group photo together, everyone moved to the dining hall for lunch.

Since everyone felt the discussion time was insufficient, conversations continued even in the dining hall. First, Sunim smiled and shared his impressions of what Pastor Anura presented today.

“Most politicians often express themselves by saying ‘The people want this’ or ‘Many people want this.’ But what impressed me most was that the Dharma Shakthi gathering established a principle of expressing things in the first person. We should say ‘I think this way,’ but most people generalize by saying ‘The people want it this way.’ This seemed like an important principle for bringing about reconciliation.”

They shared their impressions with each other while having their meal. After finishing lunch, they got back in the car and returned to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

They moved to the lounge on the second floor and had tea together. The discussion continued. Although the pace was slow due to the need for interpretation, everyone concentrated on each word with deep interest in one another.

After finishing tea, everyone headed to the International Conference Hall on the 6th floor. From 2 PM, a conference began on the theme of “Asian Interfaith Dialogue for Reconciliation and Peace” with about 40 participants including senior members of society, religious leaders, and civil society activists. Organized separately by The Peace Foundation from the International Reconciliation Society, this was arranged as a space for more in-depth dialogue.

With Father Kim Hong-jin as the moderator, after introducing the participants, the conference began with loud applause.

Bishop Park Kyung-jo of the Anglican Church of Korea gave the welcoming address for the afternoon conference.

“Pope John Paul II once confessed and repented for the historical errors committed by Christianity. He repented for the wrongs committed by the Church, including the Crusades, religious trials, persecution of Jews, suppression of religious freedom, discrimination against women and minorities, and unfair treatment of scientists. I hope we gathered here can also first have a time to confess our sins while looking back on the years we have walked. After that, I hope this can be a time to diagnose the present and look toward the future.”

Following this, Pastor Anura introduced Dharma Shakthi’s activities in detail. Everyone expressed their respect and gave loud applause for the dedicated activities of religious people who have worked to resolve conflicts in Sri Lanka.

Next, former Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism Do Jong-hwan came up to the stage and gave a welcoming address.

“I think a society of distrust has been created because everyone believes only their own thoughts are right and doesn’t think that their thoughts could be wrong. Reconciliation and peace must start from acknowledging that my thoughts could be wrong. I hope that through today’s gathering, your efforts for peace in Asia can be conveyed to many others.”

Following this, Sunim came up to the stage and responded to former Minister Do Jong-hwan’s congratulatory remarks.

“Religion values faith most highly, teaches peace, and teaches love. However, religion in reality promotes hatred rather than love and becomes a cause of conflict and disputes rather than peace. When I think about why this contradiction occurs, after listening to former Minister Do Jong-hwan’s words, it seems the cause is ‘conviction in belief.’ That’s why there’s a saying that ‘the most dangerous thing in this world is conviction.’ Yet we highly value and like conviction. However, we must realize that conviction becomes the cause of all conflicts.”

Sunim then briefly introduced the work that the religious gathering has done so far. After Sunim’s presentation ended and a short break, the discussion session continued in earnest.

Participants asked various questions about Dharma Shakthi’s peace practice methods and showed great interest in how that experience could be applied to the division situation on the Korean Peninsula. Various questions followed about when and how Dharma Shakthi started, what its decision-making structure is like, and what political considerations the Sri Lankan government has made since the ethnic conflict. Pastor Anura explained, “Armed conflict has ended, but political conflicts remain,” and described the government’s reform attempts including constitutional amendments, expansion of minority autonomy, and changes in language policy.

Former National Assembly member Kim Sung-gon asked Venerable Pomnyun Sunim about his thoughts on the need for dialogue between Christianity and communism, observing conflicts within Korean society. Sunim answered this question.

Isn’t Reconciliation Between Christianity and Communism More Important Than Interfaith Dialogue?

“You’ve made a good point. From the progressive forces’ perspective, inter-Korean dialogue is defined as ‘North-South dialogue,’ but conservative forces view it as ‘dialogue between progressive forces.’ Therefore, North-South dialogue promoted by progressive governments is not accepted as genuine North-South dialogue. For inter-Korean dialogue to become genuine dialogue, South Korea’s conservative forces and North Korea must engage in direct dialogue. That’s why when progressive forces promote North-South dialogue, it must always be accompanied by certain support and agreement from conservative forces for the dialogue to have sustainability. Otherwise, as has been the case until now, when a progressive government comes to power, North-South dialogue takes two steps forward, but when a conservative government comes to power, it takes two steps back again. Therefore, during progressive government periods, rather than hastily moving two steps forward, there needs to be agreement to move one step forward with partial consensus with conservative forces, and conservatives should agree not to retreat from that position.

However, more fundamental than this is ‘dialogue between North Korea and the United States.’ If North Korea and the United States normalize relations through dialogue, the hostility of South Korean conservative forces toward North Korea will also be significantly alleviated. This is because the support base for South Korea’s conservative forces is the United States. Ultimately, only when America’s position changes can the position of South Korean conservative forces also change. Therefore, to fundamentally resolve the Korean Peninsula issue, dialogue between South Korean conservatives and North Korea is important, but more important than that is ‘normalization of relations between the United States and North Korea.’ In the end, we should not only consider ‘how to dialogue with North Korea’ but also consider together ‘what South Korea can do to enable dialogue between the United States and North Korea.’

Therefore, dialogue between South Korean conservatives and North Korea can be called ‘dialogue between South Korean Christianity and North Korea’ as the questioner mentioned. However, it is realistically difficult for South Korean Christianity to engage in direct dialogue with the North Korean government. This is because it is virtually impossible for the North Korean government to dialogue with specific religious forces.”

Former UNESCO Secretary-General Lee Sam-yul asked whether there is discrimination in exams or administration despite Sri Lanka’s official recognition of Tamil as an official language. Darshaka, a Hindu priest, responded to this question.

“While Tamil is constitutionally an official language, problems arose when past politicians emphasized only Sinhala. Currently, civil servants are required to use both languages, and English is used as a common language in education, administration, and healthcare to minimize discrimination. University exams can also be taken in each language, resolving 90% of language discrimination issues.”

Joo Sun-won, Standing Chairman of the Donghak National Unification Association, asked whether foreign influence affects religious conflicts in Sri Lanka and whether they maintain an autonomous stance. Firdous, a Muslim leader, responded to this question.

“While foreign intervention always exists, Dharmashakti has treated all ethnic groups and religions equally and resolved internal problems independently. We firmly oppose extremism and foreign interference, pursuing cooperation among all members as one.”

Standing Chairman Joo Sun-won asked Sunim whether achieving peace on the Korean Peninsula requires a balance between autonomy and openness. Sunim responded to this question.

Don’t We Need to Consider the Spirit of Autonomy Beyond Conservative and Progressive Labels?

“I generally agree with your perspective. However, we must also consider that the concept of ‘autonomy’ can sometimes lead to the side effect of being closed-minded, while conversely, an overly ‘open’ attitude can lead to foreign dependence. The fundamental difficulty North Korea faces lies in its closed autonomy. On the other hand, South Korea has developed based on openness but also carries the side effect of foreign dependence. Therefore, we should not view this issue too definitively but always look at both sides together.

Additionally, the world has changed significantly. The international situation immediately after liberation is very different from the current situation. We should not evaluate the present through the lens of the past but must view it considering the changed global circumstances. The biggest problem around us now is the hegemonic competition between the United States and China. South Korea, North Korea, and even Japan are all being swept up in this massive wave. While inter-Korean conflict was central in the past, cooperation is now more beneficial for us.

Although we suffered greatly from Japan in the past, mutual cooperation is more beneficial to respond to the current changed situation. We must not forget the past, but we also cannot remain complacent there. We must think critically about what is most advantageous for us in the current situation and how we should respond. From that perspective, I don’t think an attitude of excessive attachment to the past is desirable. While I agree that such tendencies existed in the past, I don’t think we should insist on the same perspective now. While it’s important to center ourselves, if that becomes stubbornness, it’s not true autonomy. We must always move forward while examining changing circumstances.”

Participants wanted to ask more questions, but it was time to wrap up. Due to the need for consecutive interpretation, even conveying brief content took a considerable amount of time.

Though it was regrettable to end the dialogue, former Patriarch Park Nam-soo, chair of the Religious Leaders’ Meeting for National Reconciliation and Peace, delivered closing remarks. He emphasized the tradition of cooperation among different religions during the March 1st Movement and urged everyone to work together to overcome future crises.

“Seeing Sri Lankan religious leaders working to achieve peace in a war zone has made me reflect deeply. We are now in an era of climate crisis, life crisis, and peace crisis. To overcome these crises, all religious people must come together.”

Sri Lanka’s 30-year peace journey demonstrated how religion can save lives and connect communities even amid a history of conflict. Through today’s conference, Korean religious leaders were able to receive great inspiration.

Everyone took a commemorative photo together and concluded the dialogue session.

Sunim shook hands with each participant as they left the venue and expressed his gratitude.

“Thank you for coming from so far away.”

After all participants had left, Sunim moved to the basement dining hall with the Sri Lankan religious leaders for dinner.

After finishing the meal and ensuring everyone could rest early, Sunim headed to the Peace Foundation conference room. A journalist from Won-gwang magazine from Won Buddhism had requested a brief interview with Sunim. Sunim gladly agreed to the interview.

The journalist asked various questions about how Sunim views the future of the religious leaders’ meeting that has continued for 27 years, what has been the driving force behind Sunim’s long-standing peace movement work, and what he thinks are the challenges facing Won Buddhism.

Finally, the journalist asked if there had been any conflicts among the religious leaders during their meetings. Sunim answered with a smile.

Have There Been Any Conflicts Among the Religious Leaders During Your Meetings?

“If this meeting had aimed for interfaith dialogue, conflicts might have arisen with statements like ‘Buddhism is this way’ or ‘Christianity is that way.’ However, we leave each person’s religion to their individual faith and focus together on how to help North Korea and how to achieve peace on the Korean Peninsula. These matters can be resolved through coordination of opinions, not through conflict. For example, during the last election, there was talk of issuing a statement. Our meeting operates on the principle that we don’t do anything unless everyone agrees unanimously.

The Sri Lankan people must have been very cautious when starting dialogue since they came as representatives of groups with internal conflicts. If we had met representing workers or businesses, we would have faced similar difficulties. But we don’t represent each religion. We simply gather as religious individuals; I’m not here representing Buddhism. Despite our different religions, we focus on common tasks like environmental issues, humanitarian aid, and peace. We’ve reached some level of coordination on seeking integration in domestic conflict situations. However, there are slight differences of opinion when inter-Korean conflicts intensify or when we need to take a different path from government policy. But there are no interfaith conflicts in this meeting. If someone doesn’t agree, they can simply leave on their own. (laughs)

Since people who had worked together for several years on helping North Korean compatriots naturally came together, there were no particular conflicts of opinion. This meeting has no representatives or official positions. From the beginning, we thought of ourselves as merely errand runners and didn’t define ourselves as an independent organization. We’re carrying out our meetings with the mindset of playing the role of running errands on behalf of religious people so they can unite their hearts when there are events or activities for peace.”

After finishing the interview, Sunim concluded today’s schedule after 8 PM. He reviewed manuscripts and attended to various tasks before going to bed. It had been a long day.

Tomorrow, Sunim will visit Kyungdong Church, the Central Temple of Cheondogyo, the Jogye Order Administrative Headquarters, the Anglican Cathedral Church of Seoul, and the Dorasan Unification Observatory together with the Sri Lankan religious leaders’ group. They will tour each location and engage in extensive dialogue at each venue.