Jul 2, 2025 – INEB Day 7, Seoul, Discussion on Social Engagement

Hello. Today is the seventh day of the INEB Study Tour. In the morning, Sunim conducted a live broadcast of the Weekly Dharma Assembly for Jungto Society members, and in the afternoon, he continued discussions with INEB participant monks on the topic of “social engagement” at the Jungto Social and Cultural Center in Seoul.

After completing morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. Today was the day for the Weekly Dharma Assembly, where Jungto Society members reflect on their practice.

With about 80 members of the Sangha seated in the Dharma Hall on the third floor, the Weekly Dharma Assembly began at 10 AM with the recitation of the Three Refuges and the Heart Sutra. Jungto Society members from across the country joined online via live broadcast.

After watching a video of Jungto practitioners’ activities from the past week, the assembly requested a Dharma talk from Sunim with three prostrations. Sunim began his talk by introducing the INEB Study Tour program currently taking place at Jungto Society and explaining the international solidarity work that Jungto Society is engaged in.

“Jungto practitioners, how have you been this past week? I’ve seen through the weekly activity reports how diligently you’ve been volunteering at various main temples and locations. This week in particular, seven monks from Southeast Asia are visiting Jungto Society through INEB (International Network of Engaged Buddhists). This visit marks the 10th study tour.

Jungto Society and INEB: A 10-Year Journey Connecting Practice and Dharma Propagation

This time, rather than first-time visitors, we have participants who have visited Jungto Society once during the past 10 years and who hold certain positions while working in various fields such as education, environment, and practice in their own countries or regions. This visit goes beyond simply touring Jungto Society. Each participant has fully presented their activity cases on the theme of ‘How do we practice, educate, train, and organize volunteers to carry out Dharma propagation and social engagement?’ They’ve also learned about related Jungto Society activities and discussed together how to apply these to activities in their own regions.

Beyond sharing experiences with each other, since Korean society has changed about 20 to 30 years ahead of Southeast Asian societies, looking at Korea’s present allows us to anticipate how Southeast Asian societies might change in the future. This provides an opportunity to learn good aspects in advance and examine how to prevent undesirable aspects. In particular, the rapid collapse of rural Korean society is often described with the term “regional extinction.” Since Southeast Asia is also a society centered on rural areas, as industrialization progresses, Buddhism based in rural areas will inevitably be shaken. Additionally, without measures to address people migrating to cities or going abroad for work, even Buddhist-centered countries are likely to transform into multi-religious societies. However, if one remains only in their region, it’s difficult to know how their society will change. Only by looking in from the outside can one gauge future changes in advance and find appropriate countermeasures.

Jungto Society’s Global Practice of Sharing Buddhist Wisdom with the World

The experiences from Jungto Society’s activities should not remain as our own property or legacy, but should be shared with other Buddhists who share our vision, as well as people of other religions and nations, to help alleviate and prevent human suffering. Even if there are shortcomings, I hope our experiences can be shared and provide good learning opportunities for them. With this intention, Jungto Society has been continuing the INEB Study Tour program every year.”

Following this, those who had registered questions in advance took turns having conversations with Sunim. After one person asked a question online, three people from the on-site audience raised their hands and asked Sunim questions. One of them sought Sunim’s advice, saying that while their mind had become more peaceful since starting practice, there were times when life felt meaningless, and they wondered if they were practicing correctly.

Why Does Everything Feel More Futile the More I Practice?

“There doesn’t seem to be any particular problem yet. Actually, it’s true that everything is futile. However, your current state is somewhat overflowing. You know when we drive screws into walls? We need to tighten the screw just right, but if we overtighten it, the screw just spins freely. Have you experienced that? It means the screw has stripped and no matter how much you turn it, it just spins. It needs to be tightened just right, but it’s been overtightened. You’re in a somewhat overflowing state right now. (laughter)

The meaning of ‘impermanence’ is that since nothing is unchanging, there’s nothing to be attached to. But you’ve gone beyond realizing ‘there’s nothing to be attached to’ and have overflowed into thinking ‘it’s all meaningless,’ ‘there’s no point in doing anything.’ When scriptures say ‘the world is impermanent,’ it doesn’t mean everything is meaningless, but that things change and therefore there’s nothing to be attached to. Change means things don’t stay still but keep transforming. That’s why there’s nothing to be attached to. But you’re now thinking, ‘Why live when we’re going to die anyway?’, ‘Why see flowers when they’ll wither anyway?’ – accepting everything as meaningless. This is a somewhat overflowing state. If it overflows too much, you need to go to the hospital. Because if it overflows further, suicidal impulses might arise. The meaning of life disappears. ‘What’s the point of raising kids? They’ll figure out their own lives anyway.’, ‘What’s the point of taking care of my appearance? I’ll age anyway.’, ‘What’s the point of prostrations? My legs just hurt.’ When everything becomes meaningless like this, eventually the meaning of life itself disappears. This could lead to suicide. It’s not just you – among practitioners, about one or two out of a thousand overflow like this.

Even during the Buddha’s time, there were people who committed suicide for this reason. While contemplating corpses to realize that there is nothing to be attached to in this body, some went too far and concluded that ‘there is no meaning in living.’ You seem to be experiencing a similar side effect, progressing toward thinking ‘what’s the point of living.’ If it reaches that stage, you need to see a doctor. However, your current state seems to be one of emptiness after letting go of attachments. It’s like feeling restless after quitting smoking or feeling empty in the evenings after quitting drinking. It’s the same when fasting. You’re hungry, but when you fast, you have nothing to do. Normally, you prepare food to eat, wash dishes after meals, have dessert, and drink tea. Before you know it, it’s time for the next meal. But when you fast, you don’t need to prepare food or wash dishes, so you suddenly have extra time. Even people who are always pressed for time find themselves with too much time when fasting, and that time feels boring and empty. This feeling is exactly the emptiness you feel when you let go of something you were attached to.

When you stop being absorbed in something, you don’t know what to do with yourself. People who quit their jobs also don’t know what to do at first. This is called withdrawal symptoms. It’s the same for people who used drugs. So after attending the Awakening Retreat, you’re experiencing something like withdrawal symptoms. After being attached and then letting go, you feel like you should grab onto something again, but there’s nothing appropriate to grab, so you think ‘it’s meaningless.’ But it will get better after a while. Have you heard the saying that unemployed people die from overwork? When you let go of things you were attached to, like your child’s exams or makeup, at first you have nothing to do, but after a while, good things like studying sutras will fill that empty space. Then this sense of emptiness will naturally disappear. You can see it as a process. Watch it a bit longer, and if the feeling of emptiness lasts too long and everything becomes bothersome, then you can ask questions again or voluntarily go to the hospital.

From what you’re saying, it seems you’re currently wandering a bit due to the emptiness that comes from letting go of what you were tightly holding onto. It’s not yet at the level where you need to go to the hospital, so it would be good to observe a bit longer.”

“Could it be because I’m progressing through the practice process too quickly?”

“That’s not it. It’s a phenomenon that comes from letting go after being too strongly attached. If your attachment had been weak, this problem wouldn’t arise just from letting go. Because you were holding onto something tightly and then suddenly let go, a large empty space has formed in your mind. That’s why everything feels meaningless. When you’re attached to flowers, it’s nice when they bloom but sad when they wilt. Practice is about not being attached to flowers. Going one step further, when you understand the principle of flowers blooming and wilting, you’re happy when they bloom and happy when they fall. It’s not ‘what’s the point of being young when we’ll grow old anyway,’ but knowing that whether young or old, the present moment is always the best – that’s what practice is.”

“I understand. Thank you.”

“If you used to bow desperately to seek blessings, now you bow to let go of your ego and obstinacy. If you used to go to the temple to pray for your own blessings, now you go with a heart of greeting out of respect for the Buddha. From this perspective, bowing itself is not a problem. What matters is the mind with which you bow. If your son has an exam coming up, whereas before you clung to prayers thinking ‘I hope he passes,’ now you should have the perspective of ‘let me help my child study with a more peaceful mind.’ How anxious must the child be? If the mother adds pressure too, the child becomes even more suffocated. You should have the perspective of bringing a glass of juice or gently empathizing with the child’s difficulties. This doesn’t mean neglecting them, thinking it doesn’t matter whether they pass or fail since it’s all the result of causes and conditions. You need a perspective of observing with interest without being attached like before.”

Questions continued to follow.

When spreading the Dharma to acquaintances who say they are already happy, how should I approach and converse with them?

We are planning to establish a multicultural center at the Seoul Jungto Social and Cultural Center. I would like your advice on organizing international student meetings, foreign worker meetings, and mental care programs.

When removing lanterns and lantern tags, a lot of waste is generated. What if we add an option when applying for lanterns to pay the lantern fee without actually hanging one?

As the conversation continued, it was time to conclude the assembly. Looking forward to meeting again at the same time next week, the Weekly Dharma Assembly ended with the Four Great Vows.

After lunch, Sunim worked in his office while waiting for the INEB participant monks to arrive.

Meanwhile, the INEB participant monks who had departed from Silsangsa Temple after the morning farewell ceremony visited Jukrim Jeongsa Temple in Jangsu, the main temple of Jungto Society. After receiving a detailed explanation about Master Yongseong’s life, they arrived at the Seoul Jungto Social and Cultural Center at 3 PM.

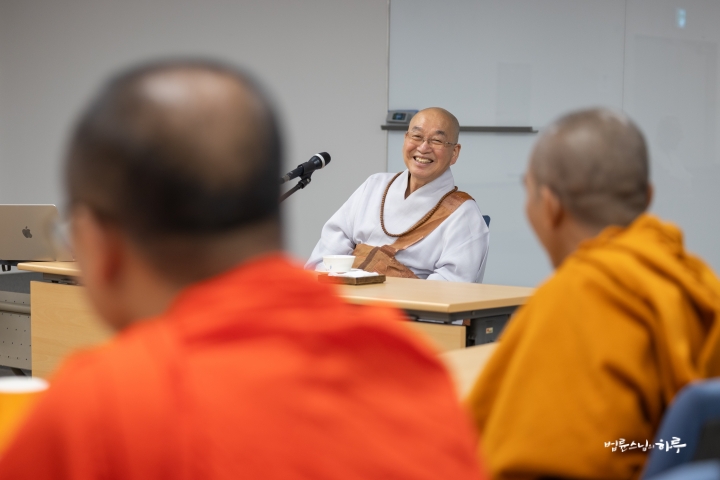

After unpacking and taking a rest, they began their dialogue with Sunim at 4 PM in the 9th floor auditorium. First, Ven. Khongsin from Thailand introduced his social engagement activities.

“I work in the Thailu community in northern Thailand. This is my hometown where I was ordained, and now I work with the community to develop traditional local beverage products and preserve regional culture centered around the temple. The temple features ancient architecture from the Lanna Kingdom period, with murals depicting the Buddha’s previous lives, making it a tourist attraction as well.

I also run a school for novice monks, helping poor children who have difficulty accessing education to stay at the temple and study through ordination. Recently, as fewer children are becoming ordained, I’m considering transitioning to a private school that combines vocational education. Traditionally, temples were centers of education where people learned skills and herbal medicine, so I want to create a model that combines Buddhist education with practical life education.”

After Ven. Khongsin finished introducing his activities leading regional culture and education with the temple in the Thailu community, Sunim posed a practical question.

“Do you necessarily have to ordain children as novices to run the school? Why not just gather local children and educate them?”

Ven. Khongsin explained the background of running the novice school.

“Starting 30 years ago, many rural temples were abandoned due to lack of monks. After much deliberation with my teacher, we created a school for novices. The children stay at the temple, receive education, and are helped to live as practitioners in regional temples.”

Sunim asked again.

“If only about 10% of those who ordain as novices eventually receive full ordination, is it necessary to ordain them for education? Wouldn’t it be more effective to accept them as regular students and combine vocational education?”

Ven. Khongsin nodded and replied.

“You’re right. These days, fewer children are becoming ordained, and there are limitations with just a novice school. When novices go to vocational schools, they easily disrobe in the free atmosphere. So we also feel the need to transition to a private vocational education school that accepts regular students as well.”

Sunim agreed.

“Seeing novices in robes receiving technical education might seem awkward from the outside. It seems more appropriate to transition to a private school model where both novices and laypeople can attend together and learn life skills.”

Ven. Khongsin responded, “We will prepare to move in that direction,” and decided to explore new approaches.

As they conversed, it was time for dinner. Sunim discussed the topics they would explore in depth from tonight until the end of the INEB program.

“Starting tonight, let’s have each of you present two or three things you want to do now or must accomplish within the next three years. After the presentations, we’ll discuss how we can cooperate to help each other achieve these goals.

How to Practice the Buddha’s Teachings Today

First, we need to agree on what we consider the core of the Buddha’s teachings and how we will work together. We must all accurately understand and share the fundamental teachings. Centering on teachings like dependent origination, the Middle Way, and the Four Noble Truths, we need to gather opinions on how to understand these from what perspective and practice them in daily life. We also need to explore how to convey these teachings to people and help them actually escape from their suffering. Thus, we must first establish our common position on the Buddha Dharma. Additionally, we need to remove the mythical aspects from the Buddha’s life and properly understand his life within history and society. We must establish an image of the Buddha that even today’s young generation can respect as our teacher and someone they want to emulate.

Another discussion is about how monks and Buddhist practitioners can practice in daily life. One aspect is education, another is practice, and finally, we must consider how to spread this Dharma widely. Education, practice, and propagation must become our important concerns. We also need to think about what roles monks and Buddhist practitioners should play in modern society. We are already practicing cooperation with local communities, poverty reduction, disaster relief, environmental protection, social justice, and peacekeeping to some extent, but we must expand these efforts in the future.

These tasks can be pursued jointly with combined efforts, or even if practiced individually, we must continue sharing experiences and helping each other learn. Even if we cannot fully address everything this time, it would be good if we could discuss these topics together at the closing session.”

After having time to reflect on the topics Sunim had suggested, they had dinner. Following a simple refreshment of snacks and beverages, they gathered again in the 9th floor auditorium at 7 PM.

Sunim reminded everyone of today’s discussion topics.

“After touring Jungto Society and Silsangsa Temple and listening to each other’s presentations, have you thought about what kinds of activities you might pursue in the future? Jungto Society and Silsangsa Temple have been engaged in these activities for over 30 years. It’s difficult to start like this from the beginning. So I hope you’ll take ideas from here and steadily develop them in your own way. As we saw in Venerable Kongsin’s example today, we’ll have time for each person to present what they plan to do over the next three years, so please prepare in advance.”

First, they had time to gather collective wisdom about what Venerable Kongsin could do in Thailand. Venerable Kongsin shared three plans he wanted to focus on over the next three years.

“First is education. Particularly, we need education that teaches novice monks literacy and basic English skills, as well as life skills for taking care of themselves as monks. Second is vocational training for villagers. I want to create a circular structure where local residents learn livelihood skills centered around the temple, and through this, support the temple and school. Third is elderly care. There have been people who committed suicide in loneliness, so I’m thinking about how to help the elderly live more happily.”

Sunim provided practical advice on each item step by step.

“If you want to provide good education, you first need to secure competent teachers. But good teachers ultimately need stable salaries to stay. While buildings can be built with a one-time investment, salaries must be paid monthly, so the key is creating a system to recruit regular sponsors.”

They continued to share opinions about ways to improve regional income.

“It’s not easy for a monk to lead the regional economy. Organic farming has low profitability and requires much labor, making it difficult for residents to readily accept. Unless it’s in a suburban area with premium consumers, it’s difficult to succeed economically.”

Venerable Kongsin introduced an herbal juice being developed as a local specialty product, mentioning the possibility of a revenue model through commercialization.

“While weaving has limitations because the craftspeople are elderly, I think we could make the juice into a unique regional beverage. I’m thinking we could promote it to tourists with the concept ‘When you come to Nan, try this juice!'”

Sunim carefully evaluated this possibility.

“To sell it as a food product, you need facilities and safety standards above a certain level. Ultimately, it needs to be operated in factory form, which requires initial investment. While profits could supplement school operations, there may be limits to significantly raising the income of all local residents. Also, though not included in current plans, we need to consider the necessity of educating women alongside the existing novice monk education. Women tend to have greater gratitude and desire to give back for what they’ve learned, so there’s a high possibility they’ll join as volunteers in the future.”

They then received suggestions from other monks. Venerable Prawin suggested that “Venerable Kongsin’s community already has great potential, and with a strategic approach, it could receive more external support,” proposing network connections. He also advised, “Beyond just juice, consider other products using local specialty seaweed and such.”

Finally, Sunim added a word for Venerable Kongsin.

“Educating poor children, helping monastics, and teaching self-reliance skills is not just a business but a Buddhist practice. If you operate these activities with sincerity and share the content with people, you will surely draw more support and participation.”

It was a time when Venerable Kongsin’s sincere concerns met with the wisdom of various Dharma friends to illuminate the path forward. They hoped that this intention would be well conveyed and bring warm winds of change to the Tai Lue community as well.

After spending about an hour discussing Venerable Kongsin’s activities, Sunim introduced what JTS is currently doing in Bhutan.

“Let me briefly introduce how JTS prepared and proceeded with sustainable development projects in Bhutan. The topic I was initially interested in was ‘How can we achieve sustainable development in the era of climate crisis?’ For sustainable living, we need ‘development that pursues consumption cessation’ – solving human poverty problems while stopping unnecessary consumption.”

An Experiment in Sustainable Development Beginning in Bhutan

“While looking for a country suitable for such an experiment, I reviewed three countries – Bhutan, Laos, and Guyana – and determined that Bhutan was most appropriate. Bhutan is a ‘carbon negative’ country with negative carbon emissions, and its national goal is GNH (Gross National Happiness). When I visited Bhutan directly and met various people including the GNH director, it was different from what I had seen from outside. GNH existed only as a concept without a practical model. A few months later, the King personally invited me, and I had a conversation with him. The King was more interested in developing a new city called ‘Mindfulness City,’ which was a plan to develop the Gelephu region of Bhutan into an eco-friendly new city like Singapore. Fortunately, he also agreed to my proposal and sent the Royal Secretary and Cabinet Secretary, so we decided to proceed with the project. It took about two years to sign the main contract with the Bhutanese government.”

“During that time, I visited Bhutan eleven times and surveyed all 65 chiwogs in 2 districts. Only through such thorough review can a project be successfully carried out. The initial plans were also gradually modified during the process. For example, we tried to combine income generation projects with living improvement projects for residents, but since income generation projects seemed difficult, we decided to proceed with living improvement projects first.”

“We conducted pilot projects in about twenty locations for one year. We built or repaired houses, installed irrigation channels and water supply systems, built fences, paved roads, and repaired schools while checking how much budget was needed and what level of resident participation there was. The most difficult part was improving the awareness of civil servants. They were somewhat burdened because they didn’t receive extra salary for this work, and it wasn’t a government project but the government had to oversee it. So we held workshops to help civil servants fully understand.”

Next, participants watched videos showing Sunim visiting villages in Bhutan and conversing with local residents, as well as Bhutanese government officials conducting workshops with Sunim and implementing pilot projects.

After watching the videos, Sunim concluded today’s discussion with closing remarks.

“The Bhutan sustainable development project was possible because we conducted thorough preliminary surveys and established clear operating principles. To be sustainable, we must minimize costs, use local materials, and rely on the villagers’ skills. This way, residents can maintain and repair things themselves later. All benefits go to the villagers. Additionally, work should be done together as much as possible, without destroying the environment, and even if the process is somewhat difficult, it should generate joy.”

“During our first visit, everyone just asked for things – ‘Buy us cattle,’ ‘Buy us smart TVs.’ However, through multiple visits, we had many conversations with residents, asking them what they would do if it were their own situation, helping them change their perspective. After having sufficient discussions with residents several times in this manner, we are now ready to have serious conversations with government officials.”

After the conversation, the INEB participant monks had a mindful sharing session.

Sunim immediately moved to the reception room on the 10th floor for an online meeting with The Chestnut Family Foundation.

Teresa, the wife, was a former pediatric nurse who has always been interested in improving children’s lives. Her husband Ben is the CEO of a global software company headquartered in Atlanta. The couple helps poor children around the world every year and has recently been providing substantial support through JTS America.

Today’s meeting was arranged to explain the progress and vision of JTS’s sustainable development project in Bhutan and discuss future collaboration directions. Sunim first expressed deep gratitude by mentioning the activities accomplished over the past few years with support from the Chestnut Foundation.

“In Mindanao, Philippines, we used to build two or three schools a year with our own resources, but now with your support, we’re building 10 schools a year. In the earthquake-affected areas of Syria, we successfully built a large school for 4,000 students with your support. We were able to provide such large-scale support thanks to the Chestnut Foundation’s sponsorship. I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere gratitude.”

He then explained in detail the background and direction of the Bhutan project.

“The Bhutan project goes beyond traditional ‘poverty relief’ to experimentally implement a vision of ‘sustainable development’ suited to the climate crisis era. While we previously focused on helping only those in need, this time we’ve selected specific regions to improve residents’ lives while preserving traditional culture and the environment. We selected two of Bhutan’s 20 districts – the poorest and most remote – as pilot areas, where various projects are being promoted including housing improvements, water supply installation, road paving, elderly medical support (hearing aids, dentures, cataract surgery), and school environment improvements. Last winter, I spent over a month visiting every village in the target areas. We plan to continue promoting this project with many volunteers.”

Sunim spent two hours providing detailed answers to questions from the Chestnut Family Foundation. After listening to Sunim’s explanation, Richard, the foundation’s staff member, shared his thoughts.

“I’ve been closely following the early phase of the Bhutan sustainable development project. The spiritual and philosophical foundations of this work align closely with the way our foundation thinks. We’re honored to finally meet you, Sunim.”

The meeting concluded close to 11 PM.

Tomorrow is the 8th day of the INEB Study Tour. In the morning, participants will visit the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism headquarters to pay respects to the President, Venerable Jinwoo, and hear about the Jogye Order’s future vision. In the afternoon, they will tour Gyeongbokgung Palace and Insadong with free time, and in the evening, they will continue their dialogue with Sunim.