June 29, 2025 – INEB Day 4, Discussion on Practice, Organizational Management, and Dharma Propagation

Hello. This is the fourth day of the INEB (International Network of Engaged Buddhists) Study Tour. Today, after spending the entire day at Mungyeong Jungto Retreat Center discussing ‘practice’ and ‘organizational management,’ the group moved to Seonyudong Education and Training Center in the evening to discuss ‘dharma propagation.’

At 4:30 AM, before dawn broke, the day began with morning chanting and prayer at the Main Dharma Hall. The INEB participant monks also joined in the chanting, 1000-Day Practice prayer, and 108 prostrations following the Jungto Society’s method.

After finishing the prayer and leaving the Main Dharma Hall, the dark sky gradually brightened, and the fog that had wrapped around the Huiyang Mountain slopes slowly lifted.

After taking a commemorative photo, everyone moved to the Main Practice Hall for Barugongyang (formal Buddhist monastic meal) while breathing in the clear morning air of Noejeong Mountain.

About 50 people participated in the Barugongyang, including the INEB delegation, Haengja Institute students, 100-Day Chulga participants, supporters of the Awakening Retreat, and INEB supporters.

After finishing Barugongyang, everyone moved to the Meditation Center where, starting at 8 AM, Sunim held an online Dharma Q&A session with Jungto Dharma School students.

Jungto Dharma School is a Jungto Buddhism Course program conducted in English for foreigners. Twenty-one students from nine groups in the United States, Germany, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Australia connected to the online video conference room. After reading the Three Refuges and Words for Practice, time was given to hear the students’ reflections. Although only two months had passed since classes began, students were experiencing small changes in their mindset and behavior.

The INEB participant monks also watched the live broadcast, observing how Sunim communicates with people online.

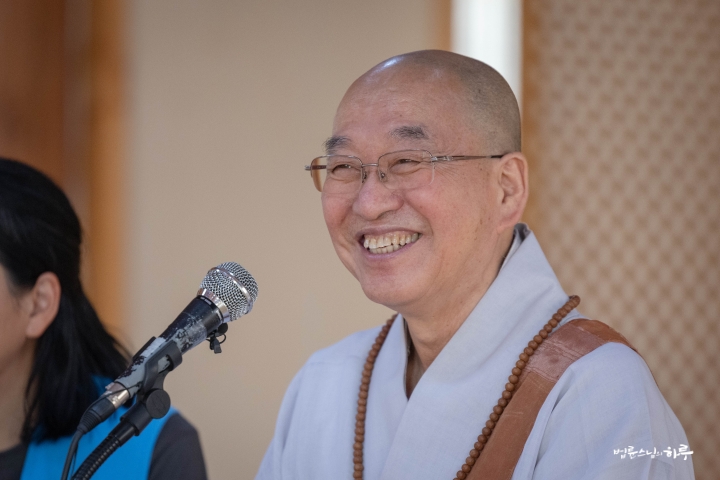

When the students requested a dharma talk from Sunim with three prostrations, Sunim emphasized the core content taught at Jungto Dharma School.

“The Buddha’s fundamental teaching is neither a religion that emphasizes specific beliefs nor a philosophy centered on knowledge. You have probably come to understand to some extent that it is a practice for managing our minds to achieve happiness. Among these, the most essential are the Law of Dependent Origination that the Buddha realized under the Bodhi tree, and the Middle Way that discovered a new path beyond extremes.

The Core of Buddha’s Teaching: Dependent Origination and the Middle Way

Taking Jungto Society as an example, individual members are not special beings. They are neither particularly virtuous nor exceptionally capable, nor do they possess special good intentions. However, depending on how the system is structured, Jungto Society as an organization can exert meaningful positive influence in the world. The Law of Dependent Origination goes beyond simply meaning ‘everything is interconnected.’ It means that when various elements form relationships, they become a new ‘one’ and within it, a third new quality emerges. So while individual ‘particles’ or ‘factors’ are important, I want to emphasize that the relationships they form are equally important. For example, even if both husband and wife are individually diligent in a family, if their relationship is poorly formed, discord and difficulties arise in the home. Relationships are not fixed but constantly changing, and the qualities that emerge from those relationships ‘do not exist independently within them.’ This is like how a car moves and makes sounds, but even if you disassemble the car, you cannot find any element that possesses ‘movement’ or ‘sound’ within it. In other words, there is function but no substance. This is precisely what Buddhism calls ‘non-self (無我, atman),’ and the constantly changing relationships are ‘impermanence (無常, anicca).’

Non-self and impermanence are the core of Buddhist thought and philosophy. Without understanding these, one cannot truly understand this world. On the other hand, the moment one realizes the Law of Dependent Origination, all afflictions disappear. That’s why the Buddha said, ‘One who sees dependent origination sees me, and one who sees me sees dependent origination.’

The second is the Middle Way. The Middle Way doesn’t simply mean the middle ground between two paths. It refers to the most correct and accurate path to reach the goal. In Chinese characters, it’s expressed as ‘Jeongdo (正道)’ using the character for ‘correct’ (正). However, this ‘correct path’ is not a fixed route. People often think ‘truth is predetermined,’ but the core of Buddha’s teaching is that ‘nothing is absolute, and the right path changes according to situations and conditions.’ Therefore, the attitude of being certain that ‘this is the truth, this is the answer’ is very dangerous. In scientific terms, it’s similar to the ‘uncertainty principle.’ Only by correctly understanding the Middle Way can we respond flexibly and accurately to changing situations. While there are countless teachings in Buddhism, I want to emphasize once again that the two most important are dependent origination and the Middle Way.”

Following this, Sunim took questions about topics that arose during the class.

When I Feel Rage at the World’s Injustices, How Should I Manage My Mind?

“When we look at many things happening in today’s world, we can say that injustice has worsened compared to 10 or 20 years ago. Inequality has grown, discrimination has deepened, and even peace is being shattered. We feel that these situations have worsened because we view the present using the past as our standard. If we set our standard at the time of fascism during World War II, we could actually say that things are better now than they were then.

What I want to say is that evaluations of whether things have ‘improved’ or ‘worsened’ differ depending on what, who, or which point in time we use as our standard. However, if we let go of the reference point itself and simply observe, we can see that ‘change has occurred.’ In other words, if we only recognize the change that ‘it was A before, but now it has become B,’ anger doesn’t arise in our minds. In a state without anger, we can choose whether to ‘accept B or return to A.’

Accepting B is simply a matter of acceptance. However, if we want to return to A, we have roles and responsibilities to fulfill. These efforts don’t guarantee success and can only be an uncertain path. Anguish arises within this dilemma. When we dislike accepting B but find the effort to return to A overwhelming, mental afflictions arise from that conflict and struggle.

Therefore, as practitioners, we must first acknowledge the current reality of B ‘as it is.’ Only then will anger not arise in our minds. However, if we still believe that A is more just, we must move toward that path. In such cases, we can say we are working for change without anger. And if we judge that to be the fastest path, regardless of success or failure, that path of change becomes our life now—the path of the bodhisattva.

No matter which country you live in or what issues you’re grappling with, if there’s something that needs to be changed, solidarity with others is essential. However, if you only cling to the standard of ‘it must be just, it must proceed correctly,’ you cannot accept change and your suffering increases. On the other hand, those who blindly conform to change accept it but cannot create change. Therefore, practitioners must face the changed reality directly and live a life that creates change when necessary, according to their pursued goals. Do you understand?”

“Yes, it was very helpful. I feel like you’ve given me a new perspective.”

Questions continued one after another. At 9:30, Sunim concluded the conversation and promised to meet again next time.

Sunim immediately headed to Jeongnyeom Hall at the Meditation Center to have a dialogue with the INEB Jungto Society visiting delegation. The conversation began at 9:45. Today’s dialogue topics were ‘practice’ and ‘organizational management.’

First, Yeo Ji-won, a volunteer from Jungto Society’s International Solidarity Team, vividly shared her experience on the topic of ‘Jungto Society’s Practice and Organizational Management,’ explaining how Jungto Society maintains its community based on individual practice.

“To become a member of Jungto Society, one must practice three things: practice, volunteer service, and donation. Jungto Society members continue their lives as practitioners by doing the 1000-Day Practice prayer daily, attending Weekly Dharma Assembly, and participating in annual meditation retreats. All activities are carried out through volunteer work, and various education and training systems are in place to help practitioners grow. We have transparent financial management and democratic decision-making structures, and we have various membership systems so that anyone can volunteer according to their situation.”

After the presentation, various questions followed about Jungto Society’s organizational management, finances, and membership system. Many specific questions arose, such as the total number of members, whether people actually became happier after becoming members, and whether Jungto Society’s structure was systematically conceived from the beginning. Through active Q&A, interest in and empathy for Jungto Society’s philosophy and operating methods deepened.

Venerable Sayadaw from Laos evaluated Jungto Society’s organizational management method as a ‘Dhamma system’ and shared his impressions after listening to the presentation.

“It seems that practitioners have developed faith in the organization called Jungto Society while continuing their practice steadily. I think this is the power of the ‘Dhamma system.’ People who come to Jungto Society to volunteer seem to have considerable spiritual power within them. Those who have experienced life transformation develop firm faith in the Buddha’s teachings. Such people won’t easily leave the organization, and naturally won’t work for other organizations. Of course, I could be wrong, but that’s what I think.”

Sunim added an explanation to this.

“Jungto Society members must volunteer their time while also doing morning practice daily. While the obligations are clear, there’s actually almost no personal benefit gained through Jungto Society. Jungto Society doesn’t teach things like ‘If you donate, you’ll receive blessings’ or ‘If you volunteer and donate, you’ll be reborn in a good place after death.’ Therefore, to continue activities for a long time, the activities themselves must become rewarding and joyful for each individual. There are three main factors that motivate Jungto Society members to volunteer.

Reasons for Sustaining Volunteer Work: Practice and Ownership

First, Jungto Society members alleviate life’s suffering, including personal and family problems, through daily practice. They resolve their issues through intensive practice sessions held at least twice a year. They also participate in Dharma Q&A at weekly Dharma Assemblies where they can talk about their difficulties. If needed, they can receive personal counseling from Dharma Teachers. In other words, they feel their joy increasing through practice.

Second, they feel a sense of pride by volunteering at Jungto Society. They develop self-esteem from doing good work. For example, when they see schools being built in earthquake-affected areas in Syria or sustainable development projects in Bhutan, they realize their donations were used meaningfully. They feel proud when they see Sujata Academy operating in India. Thus, rather than practical benefits, they gain positive satisfaction from their activities. People feel joy not only when they receive something but also when they feel ‘I played a role.’ Those who feel rewarded continue to volunteer.

Third, as they discuss, decide, and execute things together, they develop ownership thinking ‘This is my work’ rather than passively following me.

However, despite this, some people quit midway, mostly because it’s too demanding. There are cases where people quit because juggling volunteer work with their jobs and family life becomes too overwhelming.”

Next, Venerable Kittisara from Myanmar gave a presentation on the topic of ‘individual practice.’ He emphasized that mindfulness, wisdom, and restrained effort are the path to liberation from suffering and reaching nirvana. He explained the three stages of Buddhist practice as visible benefits (peace in the family), invisible benefits (spiritual growth), and ultimate benefits (wisdom and liberation).

“The ‘Bodhi Aye Nyein Meditation Center’ that I operate practices deep meditation through 45-day, 15-day, and 9-day meditation retreats that combine samatha and vipassana meditation. Another activity, ‘Dhamma School,’ has established over 6,000 schools throughout Myanmar, providing Buddhist education and moral education to youth. When wisdom and compassion come together, social practice is not a choice but a natural expression of life.”

Venerable Kittisara received great applause for emphasizing that practice, education, and social service must be connected as one.

As the conversation was deepening, it was time for lunch. Everyone moved to Jeongjeongdang Hall together for a meal.

When the INEB participant monks sat down with food on their plates, the volunteers who had prepared the meal came forward to greet them. The monks offered blessing prayers for the volunteers.

Sunim took a commemorative photo with the volunteers.

“Thank you for preparing everything with such care.”

After finishing the meal, Sunim presented a fan as a gift to each member of the INEB Jungto Society visiting delegation.

“Whenever it’s hot, open the fan and enjoy the cool breeze.”

After a short break, the conversation resumed at 1:30 PM. Venerable Dhammananda from Sri Lanka continued with his presentation.

“I established the Walpola Rahula Foundation and its research institute, WRI (Walpola Rahula Institute), in Sri Lanka. We are spreading early Buddhist education through research on the Pali Tripitaka and commentaries, and publishing Buddhist texts. At the same time, we operate ‘Interfaith Dialogue Programs’ and ‘Twin Schools’ to ease religious tensions and promote reconciliation. We also run social healing and livelihood improvement projects. WRI emphasizes the social practice of Buddhism and operates the ‘Heta BhikShuva’ and ‘Heta Pansala’ programs, which prepare for Sangha reform, temple transformation, and future monks and temples. The organization consists of a board of directors, executive committee, and volunteers, and our finances depend entirely on voluntary donations from the public.”

After finishing the presentation, the discussion began in earnest. First, Sunim emphasized the topic once again.

“The topics we want to discuss today are twofold. First, how should individuals practice? Second, how should we operate organizations based on such practitioners?”

First, Venerable Sayadaw from Laos shared his concerns.

How Can Jungto Society Operate Stably Without Government Support?

“Listening to your explanation about Jungto Society’s organizational operations, I felt it was truly remarkable. The university I belong to is run by the government. Even so, we lag behind other universities, and compared to Cambodia, Laos still has many shortcomings in various ways. One major problem is that most of the monks who work as teachers at our school return after studying abroad in other countries, but we cannot pay them sufficient salaries. This is because monks are not paid separate salaries. Transportation is also a big problem. Since accommodations are far from the school, monks have to pay for tuk-tuks out of their own pockets. So some are considering changing jobs. After finishing their studies abroad, they constantly worry about whether to continue teaching at our university or to return to lay life and pursue other careers. Even when school teachers want to repair facilities like restrooms or libraries, it’s not realistically easy. When repairing or building new buildings, we had to receive individual donations rather than government support. Despite being a government school, we face many practical difficulties. But looking at Jungto Society, it operates stably through organization alone without government support. There seems to be a big difference from us. So I’m wondering what I can do after this program ends. I would like to ask for your suggestions or advice on what direction I should take after this program ends.”

Sunim explained the path Jungto Society has taken and talked about what perspective practitioners should have regarding organizational operations.

“The five Southeast Asian countries where you are and Korea have very different backgrounds for religious activities. Since all five countries where you live are Buddhist countries, the government and Buddhist orders are very closely connected. The affairs of the religious order are often also government affairs. Even from my activities in Bhutan, I see that a significant portion of the government budget is spent on operating Buddhist temples. So government officials sometimes complain that too much of the government budget is spent on temple operations. Instead of spending money on helping people in need like JTS does, they spend a lot of budget on building temples and making Buddha statues. So from the residents’ perspective, they can’t help but complain, ‘We already don’t have enough money to spend, why are you spending so much only on temples?’ On the other hand, Korea does not establish any religion as a state religion, and government and religion are strictly separated. So we have no room to intervene in school education at all. This is because the government takes full responsibility for education. This is why we cannot do what Myanmar does.

To understand Jungto Society, you can think of Christian organizations in your countries. The government doesn’t provide them with any support, right? They operate independently without any relationship with the government. Of course, support sometimes comes from abroad, but in many cases they become self-reliant. You can understand that Jungto Society is an organization that has gradually expanded by operating in this way. So we have no choice but to have a self-reliant structure. Traditional Buddhism sometimes receives government support when temples are designated as cultural properties, and there is also tourism income. But Jungto Society has none of that – only membership fees and donations from members. It’s not that Jungto Society has more income than other temples. This is because we don’t say things like you’ll receive blessings if you donate money, or you’ll go to a good place after death. We are not a religion that prays for blessings, but emphasize practice to awaken from one’s own ignorance. So there are no acts of praying for blessings.

It actually took a long time for the current Jungto Society to come this far as a practice organization. You can understand it as a very unique case even within Korean society. Currently, Jungto Society operates entirely on a volunteer system. So we have some financial flexibility not because we have high income, but because our expenses are low.

Monks who have studied abroad tend to think of themselves as professional school teachers even after returning from their Buddhist studies, which is why they need salaries. If they weren’t monks, they could receive salaries, but because they are monks and cannot receive salaries, they have no choice but to leave. I believe this is because their perspective on practice hasn’t been fully established. The problem requires a solution either way. Either the system needs to provide stable support for their livelihood, or individual monks need to start something new with dedication as practitioners. Jungto Society can be seen as having taken the latter path. In contrast, monks in the Jogye Order currently follow the former approach as they receive support from their order.

In the case of Laos, the Buddhist order can be seen as not yet having sufficient operational capacity or organizational structure to properly develop Buddhism. The order needs to change and restructure its system to properly support these issues. While Laos may be economically challenged, the Buddhist order does receive some government funding and donations. The key is deciding where and how to use that money wisely. From what the monk who asked the question is saying, it seems they’re not investing enough in education. Ultimately, the only other option is to start a movement from the grassroots level individually, like Jungto Society. However, doing so requires facing many difficulties, as one must not only raise funds but also handle all necessary tasks independently.

People are tremendous assets, so we must value them. In the long run, securing one excellent person is far more important than constructing a building. While studying can be done even under a tree, finding an excellent teacher is not easy, is it? Of course, it would be great if the government or religious orders could provide such support, but if they don’t, we have no other options. That’s why I’m having this conversation with you all – to discuss together ‘what we can do on our own’ aside from government or religious orders. The same applies to my projects in Bhutan. It would be nice if the government supported village development, but if not, we must decide: ‘Will we just live in poverty, or will we do something ourselves'”

Next, Ven. Sovichea from Cambodia shared his experiences and concerns about running a Buddhist university in Cambodia, and Ven. Kittisara from Myanmar discussed his experiences and concerns about operating a Dhamma school in Myanmar. As the discussion concluded, Ven. Phra Win from Thailand said with a smile:

“Organizational management always comes down to three M’s: Money, Man, and Management. Without harmony among these three, no matter how good the intentions and plans are, they’re difficult to implement.”

After the heated discussion, they took a 20-minute break. During the brief rest, they watched a video of Sunim participating in coal briquette delivery volunteer work with Gilbeot, a gathering of broadcasting and cultural artists.

Sunim then explained JTS’s domestic support projects in Korea before continuing the discussion. As they talked about actions to realize social justice, the conversation naturally led to discussions about the political situations in various countries.

Ven. Kittisara from Myanmar introduced specific activities he had undertaken to eliminate discrimination and protect equal education and coexistence despite religious conflicts and political intervention. Ven. Kongsin from Thailand pointed out institutional imbalances, noting that while Buddhist monks have no voting rights, they still have military service obligations. He particularly mentioned that monks can only apply for passports under their monastic status, not as regular citizens. In response, Venerable Pomnyun Sunim emphasized that as times change, interpretations of precepts should also evolve, and monks should be guaranteed at least minimum rights as citizens.

In contrast, in Sri Lanka, monks have citizenship and voting rights and can even run for parliament, but driving vehicles is prohibited, showing that institutional contradictions still exist. This revealed how diverse and complex the relationships between religion and politics, and monks’ social rights and roles are in different countries.

In the midst of the lively discussion, Ven. Dhammananda from Sri Lanka shared his personal experience.

“It was when Sri Lanka’s economy collapsed, and about a thousand people gathered to protest. I went directly to the scene to observe and became involved. My only intention was to say, ‘Let’s not use violence.’ However, my photo was taken there, and as the protest turned violent, reports came out saying ‘This monk participated in the violent protest.’ But I sincerely wanted to prevent violence with good intentions. In that situation, I couldn’t step back, nor could I move forward. I don’t know what I should do when being attacked like this.”

Sunim responded:

“In life, people sometimes face misunderstandings unintentionally. Even if we haven’t done anything wrong, for instance, we might have an accident while driving. Just because there’s a car accident doesn’t mean we drove with bad intentions. But if someone is injured, they need treatment. Similarly, no matter how good our intentions, the outcome can appear completely different depending on how it’s received by others. Ultimately, there’s no guarantee that something done with good intentions will be fully conveyed to the other person. In such cases, we sometimes receive unwanted consequences.”

Next, Ven. Pok Pan from Cambodia asked a question:

How Can We Communicate Well?

“I’d like to hear more about Sunim’s experience. How do you usually maintain communication and relationships? I’m curious about Sunim’s communication style that helps maintain relationships.”

Sunim answered:

“I’m not good at communication either. I just manage somehow. (Laughter) If I must say, the secret to good communication is not ‘speaking well’ but ‘listening well.’ We often think communication is about ‘speaking,’ but true communication is ‘listening.’ We don’t call it communication when the other person just listens to what I say. If that were communication, then kings would be the best communicators. When a king speaks, ministers just listen. But that’s not real communication.

When a leader communicates with the people, it means listening carefully to the people’s voices. So if you want to communicate well, don’t overthink it. Just listen. However, it’s easier for us to speak our own words than to listen to others. That’s why communication is difficult. Listen more.”

There were various other questions, such as whether Jungto Society has offices overseas, whether activists’ families have ever protested or demonstrated against Jungto Society, and whether all Jungto Society monastics received parental consent since parental permission is mandatory for ordination in Thailand. After extensive discussion about organizational management, Sunim suggested:

“Let’s have a simple dinner and take a walk. We can’t just sit inside talking when we’ve come to such a beautiful place. There’s a scenic spot nearby called Seonyudong Valley.”

After dinner at 5:30 PM, they moved to Seonyudong Valley. After getting out of the car at Hakcheonjeong, they walked together along the mountain path following Seonyudong Valley.

The cool sound of water flowing along the valley seemed to refresh even their heat-weary hearts.

After returning to Seonyudong Education and Training Center, the INEB participant monks took a brief time to refresh before gathering in the main hall at 7:10 PM.

Before the evening service, Sunim announced the news of the passing of Dharma Teacher Myohyang, a member of the Jungto Society Dharma Teacher Group. The INEB participant monks expressed their desire to pray for Dharma Teacher Myohyang. Sunim expressed his gratitude and briefly introduced Dharma Teacher Myohyang.

“Dharma Teacher Myohyang passed away yesterday. She was one of the younger members of the Jungto Society Dharma Teacher Group. She joined the Jungto Society community as a university student and had been active until now. After leading the Jungto Publishing department for a long time, she was responsible for Dharma teacher education after receiving her Dharma teacher ordination. After being diagnosed with cancer, her condition suddenly worsened, leading to her passing. We are all heartbroken. But this is life – what can we do? I’m truly grateful that you will offer prayers.”

Representing the INEB participant monks, Ven. Dhammananda spoke about the meaning of this prayer.

“Venerable Pomnyun Sunim must surely want to attend the funeral of his beloved disciple due to this sad news, but nevertheless, we thank you for spending time with us today. Therefore, we also want to express our condolences together.

With the power of all the good deeds we have done in our respective countries, we pray that peace will accompany Dharma Teacher Myohyang on her journey. The ceremony we’re about to perform is a ritual to gather our sincere hearts in one place.

The empty cup symbolizes the deceased. The teapot beside it symbolizes all of us. The water inside symbolizes our gratitude for the Dharma teacher and our goodwill. Now I will pour water into the empty cup. I will pour water until the cup overflows. This means we will give our sincerity until the empty cup is full and overflowing for Dharma Teacher Myohyang’s peace.”

Ven. Dhammananda filled the empty cup with water.

They then began praying together in the Theravada tradition. After completing the prayer for Dharma Teacher Myohyang, they held the evening service.

As the sun set, the heat subsided, and a gentle evening breeze cooled both body and mind.

At 7:30 PM, they gathered in the conference room to resume presentations and discussions. Choi Ji-seon, an activist from Jungto Society’s International Cooperation Team, presented on Jungto Society’s Dharma propagation activities.

Sunim then explained Jungto Society’s Dharma propagation activities centered on practice, Dharma propagation, and social action.

“When we look at the Buddha’s life, after attaining enlightenment, he continued his Dharma propagation activities for 45 years without resting for a single moment. Spreading the Buddha’s teachings widely to people around us is a very important mission for Buddhists. This is what Jungto Society particularly emphasizes. Jungto Society holds three core values: practice, Dharma propagation, and social action. First, for oneself, one becomes a free person without suffering through practice; for others, one actively spreads the Buddha’s Dharma; and for society, one engages in social activities that realize justice and peace.

Jungto Society’s Core Values: Practice, Dharma Propagation, and Social Action

Especially for Dharma propagation, we try to maximize all available means at our disposal. Of course, showing practitioners living happily is the best form of Dharma propagation, but in modern society, that alone is often insufficient. That’s why we consistently broadcast Dharma Q&A on YouTube and share various Dharma talks through other SNS channels. We also publish books. Retreat programs like the ‘Awakening Retreat’ are open to non-Jungto practitioners and serve as good guides for those new to Buddhism.

On this foundation, the Happiness School operates. The specific channels through which Jungto Society connects with people are the Happiness School, Jungto Dharma School, and the Awakening Retreat. While publishing and SNS form a broad foundation, the Awakening Retreat, Happiness School, and Jungto Dharma School are the direct contact points where Jungto Society meets people. Going one step deeper, there’s the Sutra Course, which is also an important channel for spreading the Dharma. Additionally, social action activities indirectly help greatly with Dharma propagation. Efforts for peace on the Korean Peninsula and humanitarian aid to North Korea improve Buddhism’s external image. JTS’s various international relief activities and Eco Buddha’s environmental action movements can also convey a positive image of Buddhism to people. Through these diverse activities, we practice Dharma propagation.”

Afterwards, participants asked many questions, mainly about online dharma propagation activities, such as ‘Why don’t you use TikTok?’, ‘How can ‘A Day in the Life of Sunim’ be written every day?’, ‘How are the dharma talks selected for ‘A Day in the Life of Sunim’?’, ‘Have you experienced government censorship of SNS or attacks from comment brigades?’, and ‘What is the age and gender distribution of English YouTube subscribers?’

Venerable Dhammananda from Sri Lanka asked why Sunim adopted an open dialogue approach suitable for modern people.

How Did a Traditionally Trained Monk Come to Conduct Dharma Q&A?

“When monks receive education to take precepts, they are trained in a very traditional way, following strict and prescribed procedures for learning and speaking. However, when the Buddha spread the dharma for 45 years, meeting people and addressing their actual problems through open dialogue, he didn’t limit himself to predetermined conversations. Yet Sunim also engages in very direct and open dialogue through Dharma Q&A, not just traditional teachings. I’m curious how you can have such conversations after receiving such strict traditional education.”

“I first went to a temple when I was in middle school. In high school, I served as vice president and president of the Gyeongju Regional Buddhist Student Association. However, at that time, Korea had a traditional Buddhist atmosphere, and temples didn’t really like students coming. Students were noisy and didn’t make offerings, so temples disliked them. It was extremely difficult to find a temple for our retreats. Even when we managed to borrow a temple for practice, we were sometimes kicked out after hundreds of students gathered. The first reason was that we were too noisy, and the second was that they didn’t like seeing male and female students together, chatting and laughing. So our dream was to have a retreat center for students where it would be okay to be a little noisy.

Also, the content of dharma talks given by monks who taught students was at the level of what they would tell grandmothers, so it didn’t suit the students. So we created educational content specifically for middle and high school students and led the retreats ourselves. Later, we also gave lectures for university students. Naturally, this led me to explain things scientifically and rationally to match the students’ level. Traditional Buddhism might be wonderful inside the temple, but nobody outside knows about it, so my perspective was ‘Knowledge has value only when it’s known; what value is there if it’s unknown?’ and ‘We need to practice Buddhism that suits these young people.’ I loved Buddhism but always felt something was lacking in traditional Buddhism, so I think I studied more to give dharma talks suitable for youth and young adults. Through that process, I naturally moved toward having more dialogue with the public.”

Questions continued to flow. The INEB participant monks showed great interest in understanding the background that shaped Sunim into who he is today.

How did you gain expertise in various Buddhist traditions?

“I heard that you were involved in the democratization movement and that you previously worked as an assistant at Bongamsa Temple while still having hair. I’m curious how you gained expertise in all the various traditions of Mahayana, Theravada, and Zen Buddhism.”

“I don’t have expertise. I’m just a quack. However, I’ve always had this critical awareness. In Mahayana Buddhism, they generally reject Theravada teachings. Then when you study Zen Buddhism, they reject Mahayana. I saw this as a major problem in Korean Buddhism.

When we first learn Buddhism, we study the fundamental teachings of Buddhism. But when you actually read Mahayana sutras, they dismiss these fundamental teachings as Hinayana or ‘lesser vehicle.’ They look down on Theravada Buddhism as elementary school level while boasting that Mahayana is university level. Then when you move to Zen Buddhism, they completely reject even reading and studying sutras. So the more you study, instead of Buddhist teachings coming together in one place psychologically, the confusion only deepens. However, since you mainly study Theravada, you might not feel this problem as acutely. When you study Mahayana, it rejects Theravada; when you study Zen Buddhism, it rejects Mahayana. This inevitably led me to question: ‘What is the essence of Buddhism?’

The Buddha’s original teachings became increasingly distorted and conceptualized over time. This led to a new Buddhist movement that called for a ‘return to the original Buddhist teachings.’ However, from the perspective of established Buddhism, these people were considered heretical. They rejected them, saying, ‘What you’re doing is not Buddhism.’ In response, those advocating for new Buddhism declared, ‘You are small, and we are great,’ calling themselves Mahayana (Great Vehicle Buddhism) while disparaging the others as Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle Buddhism). However, the Mahayana that entered China became excessively academic. This prompted the emergence of Seon Buddhism, with practitioners saying, ‘This is not the Buddha’s true teaching.’ They rejected the practice of clinging to books and scriptures, calling it ‘not relying on written words,’ and instead urged, ‘Look directly at your mind as if pointing with a finger.’

From this perspective, the Buddha’s early teachings, Mahayana Buddhism, and the early teachings of Seon Buddhism can all be seen as consistent in content. This is why I no longer distinguish between Mahayana, Theravada, and Seon Buddhism. Jungto practitioners first learn the fundamental teachings of Theravada and study the Buddha’s life. For Mahayana, rather than studying all scriptures, they focus only on the early Mahayana teachings, as these align with the fundamental teachings. However, Mahayana Buddhism later transformed to almost Hindu levels. While early Seon Buddhism shared the same concerns as fundamental Buddhism, today’s Seon Buddhism has lost much of its original intuitive insight. Therefore, I and the Jungto practitioners study Seon Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism from a perspective that aligns with the fundamental Buddhist teachings.”

As the night deepened, the conversation grew deeper as well.

Sunim explained that to properly understand the Buddha’s teachings, one must remove elements of traditional Indian thought from the scriptures, and he reinterpreted the Buddha’s life from the perspective of human cultural history.

Moved by Sunim’s passionate explanation, Anchalee, who has been participating in the INEB Jungto Society visit program for 10 years, said with a smile:

“I think this is the first time Sunim has spoken so deeply about the Buddha’s Dharma. Sunim looks happy, and I’m also glad that the other monks seem to understand what Sunim is saying.”

Sunim asked in return:

“How can you tell whether they understand or not?”

Anchalee replied with another smile:

“I can tell. I think Venerable Pomnyun Sunim is the happiest person here.”

Sayadaw deeply resonated with Sunim’s explanation, saying that Theravada and Mahayana are like two wings:

“A Buddhist scholar once compared Mahayana and Theravada to the two wings of a bird. Just as a bird cannot fly with only one wing, the two must go together.”

Sunim responded:

“I believe that one must properly study Theravada to correctly understand either Mahayana or Seon Buddhism. Studying Mahayana and Seon Buddhism without knowing fundamental Buddhism is like building a second or third floor without a first floor.”

Finally, a heated discussion ensued about why the bhikkhuni ordination is not recognized in Theravada. Opinions were exchanged about the historical legitimacy and institutional limitations of bhikkhuni ordination within the monastic traditions of Sri Lanka, Thailand, Korea, and other countries. Venerable Pomnyun Sunim raised the need for Theravada to reconsider allowing bhikkhuni ordination from the perspective of gender equality.

After the passionate discussion continued late into the evening, the conversation concluded at 10 PM.

“Tomorrow we will wake up at 4 AM, have morning practice at 4:30 AM, and depart for Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center.”

Despite the packed schedule throughout the day, everyone went to bed with smiles, showing no signs of fatigue.

Tomorrow is the fifth day of the INEB study tour. After leaving Mungyeong early in the morning and traveling to Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center for a simple breakfast, the morning will include climbing Namsan Mountain in Gyeongju to visit Cheollyongsa Temple. After touring the farm at Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center, the afternoon will feature an intensive discussion session on the theme of “social engagement.”