May 13, 2025 – Day 86 of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Jungto Dharma School “Human Buddha” Lecture 2

Hello, this is day 86 of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today is a lecture day for the Jungto Dharma School.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center for his Jungto Dharma School lecture.

At 10:15 AM, the morning session of the Jungto Dharma School began. About 150 students were present in the basement auditorium, and approximately 170 more were connected to the online live broadcast.

Today is the second session on learning about the Buddha’s life. In the previous session, Sunim examined the natural environment and social and historical background of India when the Buddha was born. Starting today, he will explore the Buddha’s birth, growth, his four encounters outside the palace gates, and his path to renunciation.

After reciting the Three Refuges and Words for Practice together, and requesting the Dharma teaching with three bows, Sunim began his lecture.

“Today we will begin to follow the great journey of the Buddha’s life from birth to nirvana. In India, life is divided into four periods. These are called the four stages. The first is the learning period from birth to fifteen years of age. The second is from fifteen to thirty, when one follows one’s father to learn the family business. The third is from thirty to forty-five, when one directly inherits and maintains the family business. And the final fourth period is when one passes the family business to one’s children and enters the forest for spiritual practice, known as the wandering period.

When the Buddha was approaching adulthood, he began to venture outside the palace with his father. Following the king, his father, he started to learn the royal duties. This was the transition from learning from teachers to gaining practical experience.

The first such experience was the Plowing Ceremony. In spring, the kingdom held a major event to mark the beginning of the agricultural season. During this ceremony, the king would plow with a golden plow, the ministers with silver plows, and the farmers with iron plows. This was not merely an event announcing the start of farming but also an opportunity for the king to display his authority before his son. However, during the ceremony, they noticed that Siddhartha was nowhere to be seen. So after the ceremony ended, they went looking for him.

Siddhartha, whose name means “May All Be Accomplished,” ventured outside the palace for the first time that day and witnessed the lives of impoverished farmers. These farmers were all slaves. The social structure of India at that time consisted of nobles, who made up less than 10 percent of the population, and slaves, who comprised the remaining 90 percent. The slaves performed all labor—farming, running errands, cooking, washing, cleaning, and weaving cloth. The comfortable lives of the nobles were built upon the miserable existence of these slaves.

Is There a Way for Everyone to Be Happy Together?

The prince saw the lives of these slaves for the first time that day. The first person he encountered was a farmer. The farmer’s clothes were tattered, his body was covered in dirt, and his face was darkened by the sun. Deep suffering was etched on his face. The prince asked him:

“Why are you living in such suffering?”

The farmer replied:

“Because the officials and masters exploit us so harshly.”

Upon hearing these words, the prince gained a profound insight. He realized that the comfortable and abundant life he had enjoyed in the palace was built upon the suffering of these people.

Furthermore, the prince observed the farmer plowing the field while whipping an ox with a leather whip. The ox was foaming at the mouth and panting as it pulled the plow. The prince realized that even the farmer’s convenience was built upon the suffering of the ox. As the plow cut through the earth, worms emerged from the soil, and birds swooped down to eat them. It was a scene where one creature had to die for another to live. Witnessing this, the young boy was filled with profound questions.

“Why must one die for another to live? Why must one suffer for another’s convenience? Why must one person’s happiness be built upon another’s misery? Is it not possible for everyone to live together and be happy together?”

These questions later formed the foundation for Buddha’s response when King Pasenadi of Kosala, upon meeting the Buddha, asked, “How can I become a good king?” Buddha replied, “Great King, do not build your happiness on the misfortune of others.”

After meeting the farmer, the prince lost interest in the agricultural ceremony and sat in deep contemplation under a nearby Jambu tree. “Why must one die for another to live? Is there a way for all to live together?” He was so absorbed in these thoughts that he lost track of time. The scriptures describe this scene as follows: Initially, Siddhartha was sitting in the shade of the tree, but as time passed and the sun shifted, its rays began to shine upon him. Then, the branches of the tree moved on their own to provide him with shade. Indians believed that divinity resided in all beings. Since they believed trees also contained divine spirits, the story tells of the tree creating shade of its own accord. To understand such scriptural narratives, one needs to know the culture, philosophy, and beliefs of India.

The king, who had gone looking for his son, discovered Siddhartha quietly meditating under the tree. At that moment, seeing his son’s composed posture, he instinctively bowed to him. The king bowed to his son three times in his life, and this was the second occasion. According to the scriptures, the first was when the sage Asita prophesied that his son would become a Buddha, the second was upon seeing his son in meditation, and the third was when the Buddha returned to his homeland after attaining enlightenment.

After attending the agricultural ceremony, Siddhartha became less talkative and was always deep in thought. He also questioned his teachers about his doubts.

“Why must one die for another to live? Is there no way for all to live together?”

But no one could answer the prince’s questions. All the knowledge we learn is focused on “how can I win?” or “how can I gain more profit?” No one had asked the question, “What is the way for us to live together?” Schools didn’t teach it, and teachers had never considered such thoughts, so they couldn’t provide answers. We are always taught how to win, but in reality, most people fail and become frustrated. When children are young, they believe their parents know everything, but as they grow, they realize that even parents don’t know many things. When they brought up such questions to their parents, they simply rebuked them, saying it was a waste of thought.”

When questions yield no answers and there is nowhere else to ask, one can only contemplate alone. This is inquiry. A seeker is someone who persists in this inquiry. Merely learning and acquiring knowledge does not make one a seeker. A true seeker is someone who, like a scientist deeply researching a subject, explores their inner questions on their own.

This is how Siddhartha embarked on his path to enlightenment. From this point on, he was called a Bodhisattva. Here, “bodhi” means enlightenment, and “sattva” means sentient being. Therefore, Bodhisattva means “one who advances toward enlightenment.” Only when complete enlightenment is attained is one called a “Buddha.” Before attaining enlightenment, one is still a sentient being but is called an enlightened sentient being because they are moving toward enlightenment.

Gautama Siddhartha’s journey toward enlightenment began with clearly facing the reality of the world and becoming aware of its problems. The catalyst for this awareness was the Four Gates Excursion (Samon-yugwan). He went out through the four gates of the castle and saw the reality of the world.

Ah, sentient beings are living in such deep suffering

When Buddha went out through the East Gate, the first person he encountered was an elderly person. However, as Buddhism became institutionalized as a religion, the Four Gates Excursion was simplified, losing its historical context and social significance. It was abbreviated and passed down as “He saw an old person, a sick person, and a dead person.” This simplification left only the philosophical question, “People inevitably grow old, get sick, and die; how can one avoid aging, illness, and death?” while the social awareness embedded in the original story disappeared.

Understanding the society of India at that time, the elderly person Buddha saw outside the castle walls was not simply an old person. Were there no elderly people inside the castle? The elderly person Buddha encountered was someone who had been abandoned because of old age. Slaves who became old or sick lost their value and were discarded, and when they died, even their bodies were not properly handled. They were thrown away like garbage. The place where these bodies were discarded was called Sitarim. While the upper classes were cremated with funeral rites when they died, slaves were considered not worthy of such treatment, and their bodies were simply discarded. In Korea too, in the past, servants and slaves were not given proper graves. They were simply buried in the ground without ceremony. Even when children died, graves were not made for them. They were buried in holes dug in the mountains, covered with stones and thorny branches. There was a time when even children were not given proper burials.

When Buddha left the city gate, he encountered an elderly person without protection. The description is very detailed.

‘The old man’s hair, sideburns, and beard were as white as frost; his dark face was wrinkled and creased; tears flowed from his eyes and mucus from his nose; his teeth were all missing. His entire body was dark and wrinkled, his skin mottled with dark spots, and only bones and skin remained with no flesh, causing his neck to sag like the dewlap of a cow. His clothes were tattered and barely covered his body; phlegm gurgled in his throat, and his labored breathing made a rasping sound like sawing. His limbs trembled, and he gasped as if his breath would stop at any moment. His back was bent, causing him to walk crookedly; his body was withered, his strength diminished, his steps unsteady, and he could barely walk with the support of a cane, occasionally falling on his own and struggling to walk before the prince.’

This was not just a simple elderly person but someone described like those emaciated, skeletal elderly people one might encounter lying on the streets during a trip to India. The important realization here is that everyone ages, and I am no exception. It’s not just the fact that young people become old. It extends to the recognition that even I, as a member of royalty, will one day grow old and could even become a slave. In those times, even royalty could be killed in war or sold into slavery if defeated. In fact, during Buddha’s time, the Shakya clan was attacked by the Kosala kingdom, and most were either killed or captured and sold into slavery. That’s why the remaining descendants of the Shakya clan in India today belong to the Sudra slave caste rather than the Kshatriya warrior caste. This represents the realization that another’s suffering could become one’s own—a process of “self-identification.”

At the South Gate, he encountered a sick person. Again, this was not just an ordinary sick person. This was someone who needed treatment but instead was abandoned by the roadside. The scripture describes it this way:

‘The sick person’s body was emaciated to skin and bones, with only the belly swollen, and his complexion was not merely yellow but bluish. He coughed and retched severely; all his joints ached intensely; he was abandoned on a pile of garbage with putrid fluids flowing from nine orifices; he soiled himself with excrement and urine, sitting or lying in it, creating a terrible stench. His eyes could not see, his ears could not hear; he breathed roughly, groping the air with his hands and feet, moaning and crying out, desperately calling for “Father” and “Mother,” grieving and longing for “my wife” and “my son.”‘

Then at the West Gate, he saw a dead person. That corpse was also abandoned on the street. After a slave died, even their corpse was left unattended and unclaimed. Through these scenes, Buddha came face to face with the misery of the world—the suffering of sentient beings—with his whole being.

At the North Gate, the prince met a practitioner. Although the practitioner wore tattered clothes and had an emaciated body, his eyes shone like the morning star, and his posture was dignified. The prince asked, “Who are you?” He replied that he was a renunciant practitioner. When the prince further inquired, “What does a renunciant practitioner do?” he answered, “A renunciant practitioner is someone who abandons everything and leaves home to practice in search of truth.” From this conversation, the prince gained some insight into the questions he had been pondering. He became hopeful, thinking, “Ah, if I become a renunciant practitioner, I might find the answers,” and resolved to become one.

The timing of the Four Sights differs slightly across various sutras. Some describe that the Four Sights occurred when the Buddha was 16 years old, and he married at 19, while others state that he married at 16 and experienced the Four Sights around 19. In any case, between the ages of 15 and 20, the Buddha came to recognize the contradictions of the world as they truly were. Although he wanted to renounce the world, his parents opposed his wishes, so he could not fulfill his intention. During this time, he struggled internally while continuing to practice.

An important event occurred during this period. In India at that time, there were two ways of life. One tradition was for a father to pass his occupation to his son and then leave home to practice spiritual cultivation. However, this was a period transitioning to absolute monarchy, where kings were reluctant to relinquish their thrones until death. This led many princes to harbor resentment, overthrow their fathers, and seize the throne. The most notable example was in the kingdom of Magadha, where King Bimbisara was deposed by his son Ajatasattu. Similarly, in the kingdom of Kosala, Prince Virudhaka staged a coup and seized the throne while his father, King Pasenadi, was away.

When Buddha renounced the world, King Bimbisara asked him why he had left his life as a prince. In the scriptures, there’s a scene where the king asks if Buddha left because his father refused to pass down the throne to him. At that time, it was a cultural tradition for fathers to pass the throne to their sons and then pursue a path of spiritual practice, but as time passed, this was changing to an absolute monarchy where kings held their position until death. Looking at Bhutan today, we can see similarities to this ancient Indian tradition. The father of Bhutan’s current king is still alive and even younger than I am. Yet he passed the throne to his son 20 years ago. After abdicating, he completely withdrew from state affairs and devoted himself solely to spiritual practice. This is why he is held in such high esteem.

After witnessing the four sights, Buddha became even more acutely aware of the contradictions in the world. His parents tried to dissuade him by arranging his marriage, but even this could not change his resolve. So they entrusted him with governing a region. However, conditions there were no different from those around the palace. Farmers were in rags, and oxen were whipped as they pulled plows. There, the prince truly realized how “all beings are bound and living in suffering.” He ordered his servants to cut the reins of all animals to set them free and released all the slaves. According to these records, Buddha was the first person in human history to practice the liberation of slaves. However, such actions alone could not properly govern the region within the social system of that time. This approach was not enough to solve the problems. The prince could no longer find in the palace the answer to the question, “What approach would allow everyone to live together and be happy?” Finally, he decided to renounce the world.

After the Q&A session addressing curious questions, Sunim stepped down from the stage.

The facilitator then explained the practice assignments to the students. The students agreed to consistently practice until next week’s meeting and then participated in mindful sharing in their respective groups.

Sunim had lunch with the Sangha in the basement dining hall. At 2 PM, he met with foreign policy and security experts. As President Trump’s tariff policies were causing global disruption, Sunim engaged in a two-hour discussion with the experts about how to navigate the relationships between South Korea, North Korea, and the United States.

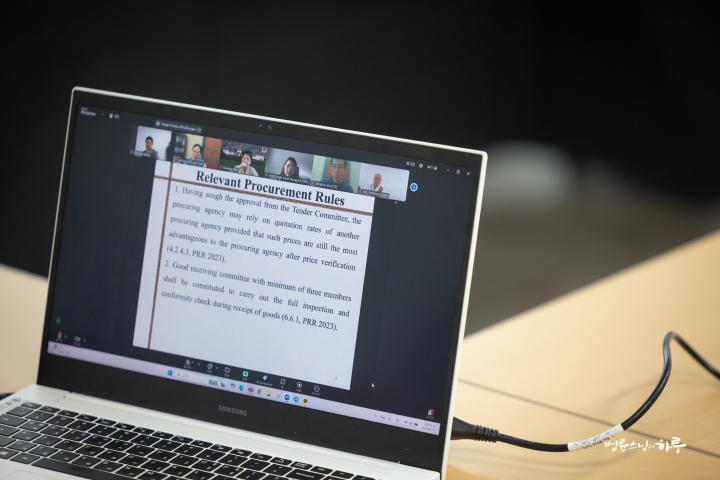

At 4:30 PM, Sunim participated online in the regular steering committee meeting between the Bhutanese government and JTS for sustainable development in Bhutan. The Bhutanese government was represented by a Cabinet Minister, the Royal Secretary, the Governor of Zhemgang, and the Governor of Trongsa, while JTS was represented by Venerable Pomnyun Sunim and Ms. Park Gena. Rinchen Dawa kindly volunteered to provide interpretation services.

First, they reconfirmed and finalized the committee structure and operational procedures that had been decided at the March steering committee meeting, with the Governors of Zhemgang and Trongsa in attendance.

Next, they presented and reviewed a draft of the budget allocation and project scope for sustainable development initiatives in Bhutan over the next three years. They agreed that Phase 1 would focus primarily on improving living conditions, including housing environment improvements, irrigation canal and fence repairs, water and road improvements, school facility repairs and educational equipment support, and medical activity support. After finalizing the project plan, the Cabinet Minister made a proposal.

“Since the main sustainable development project will begin on July 1st, I suggest that the Bhutanese government and JTS sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) before then.”

“Yes, I will be visiting Bhutan at the end of June, so we can sign it then.”

After reviewing the procurement regulations related to material transportation, the Cabinet Minister gave closing remarks.

“Since this is money that many donors in Korea have contributed with great sincerity, we will use it as economically as possible and only for essential purposes. We want all donors to feel proud of their contributions. I will report everything we discussed today to the King and provide full support.”

Sunim expressed his gratitude in Bhutanese.

“Kadrinchela.” (Thank you.)

After the meeting, Sunim had dinner in the basement dining hall.

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim began teaching the second lecture of “Human Buddha” for the evening class of the Jungto Dharma School. About 150 students who had rushed over after work filled the basement auditorium, while approximately 340 more connected to the online live broadcast.

They recited the Three Refuges and Words for Practice together, then requested Sunim’s teaching with three bows.

Like in the morning lecture, Sunim spoke in detail about the Buddha’s childhood experience at a plowing ceremony, his decision to renounce the world after the Four Sights, and the process leading up to his departure. Sunim particularly emphasized what true renunciation means while explaining how the Buddha left the palace after deciding to renounce the world.

“Despite his determination to renounce the world, the Buddha could not obtain his parents’ permission. Finally, he strengthened his resolve and set out on the path of renunciation, leaving behind his son Rahula. When Rahula was born, the Buddha thought, ‘If I don’t leave now, I’ll never have the chance.’ However, looking at Indian history and culture, Rahula’s birth might actually have been the decisive factor in his decision to leave. In India at that time, inheritance rights belonged only to males, so having a son meant fulfilling the responsibility of continuing the family line, which could have provided justification for his departure.

I renounce the world solely to find a way for all sentient beings to be free from suffering

Despite his father’s opposition, the Buddha’s determination grew even stronger. This time, his mother tearfully begged him to stay. Until then, it was his mother’s tears that had prevented him from leaving, but now even those tears could not stop him. His resolve was complete. However, this didn’t mean he had received permission to leave. Since seeking permission seemed impossible, he essentially fled in the middle of the night.

Whether this actually happened or was the writer’s imagination is unclear, but the records don’t mention the Buddha wanting to see his wife before leaving. If he had, renunciation would have been difficult. However, it’s said that he did want to see his child before his final departure. When he opened the door to see his son, the child was sleeping in his wife’s arms, and he couldn’t bring himself to hold him. Knowing that waking his wife might jeopardize his plans, he quietly closed the door and left home. This is called ‘Yuseong Chulga,’ meaning he renounced the world by climbing over the palace walls.

When we go to a temple, we often pray to the Buddha for things like “help me get a promotion,” “help me get married,” or “make my business successful.” However, the Buddha abandoned everything he had and became a monk. He gave up his wealth, his wife, his family, and even his royal position. Becoming a monk is not something one does because of failed romance, failing an exam, or being unable to find a job. Even when one has all these things, renunciation comes from realizing that they fundamentally lack meaning.

The Buddha, concerned that his father might pursue him, rode his horse through seven countries. At that time, countries were small, about the size of a modern Korean county. Only after crossing seven countries and a large river did he believe his father could no longer follow him, and he sent his attendant back. Then he cut his own hair and began his life as a monk.

Why did the Buddha renounce the world?

This scene of the Buddha’s renunciation is extremely important. We tend to view renunciation somewhat pessimistically. I’ve been asked countless times why I became a monk. People usually expect a sad story. They want to hear about someone dying, breaking up with a lover, failing an exam, a business collapsing, or marital conflicts. Even when watching TV programs like “I Am a Natural Person,” most stories are similar. People went to the mountains because their families were ruined during the IMF crisis or because they became ill. Most renunciation stories are about people who failed in society and turned their backs on the world.

What happens when one renounces the world this way? If an opportunity arises to earn more money than one’s goal, to meet someone better than a former lover, or to achieve a higher position than one’s unfulfilled dream, one will pursue these desires even while wearing monastic robes. Even among monks, there are those who crave worldly things like power, status, money, and fame. This happens because they harbor feelings of inferiority toward these things. But the Buddha’s renunciation was different. He gave up everything. He could have been a king but abandoned the throne; he had wealth but gave it up; he had a family but left them behind. In the scriptures, there is a scene where the Buddha makes this resolution as he leaves the palace:

“Unless I find the path that liberates all sentient beings from suffering, I will not return to this palace. Even if I fall to my death from the high walls, even if I die from poison, I will never return to this palace until I attain enlightenment.”

At the place where he made his decision to renounce the world, the Buddha told his attendant to return home. However, the attendant refused to leave, fearing punishment if he abandoned his master. The Buddha then gave him a token and asked him to deliver this message to his father:

“I am not renouncing the world to live well alone, nor to be reborn in heaven after death, nor because I have been deceived by others. I am becoming a monk solely to find the path that liberates all sentient beings from suffering. When I find that path, I will certainly return home and share that teaching with my family.”

In these words, we can see the Buddha’s firmness and dignity. The Buddha attained enlightenment six years after his renunciation, and after another six years—twelve years in total—he returned to his hometown to teach the Dharma to his parents, family, siblings, and friends. After hearing his teachings, many people either became monks as his disciples or followed his teachings while remaining as laypeople.

To Renounce the World is to Remove even the Possibility of a Home to Return to

Renunciation is a path toward freedom, so it should be free from any constraints. To attain true freedom, one must give up comfort. Since suffering and pleasure bind each other like chains in the cycle of rebirth, to escape suffering, one must also let go of pleasure. However, unable to abandon comfort, we continuously wander within these constraints. When home feels like a constraint, breaking free from it is renunciation. Renunciation means leaving completely, as if burning down one’s house. Simply leaving one home to find another is merely running away, while renunciation means eliminating the very concept of a home to return to.

There are two forms of renunciation. One is shaving the head, and the other is removing one’s existing clothes and wearing rags. Shaving the head symbolizes letting go of the existing social values such as ethics, morals, and customs. And removing one’s clothes signifies the attitude of abandoning all privileges such as royal status, wealth, and family. In this way, the Buddha let go of everything and began a new life as a renunciant practitioner. In other words, he made a revolutionary change.

Today, Sunim taught about the Buddha’s early life and the process leading up to his renunciation, examining what true renunciation means. The second lecture concluded with the announcement that next week’s class would cover the Buddha’s journey from renunciation to enlightenment“

Following this, the facilitator explained the practice assignments to the students, after which they gathered in groups for mindful sharing.

Tomorrow will be the 87th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will conduct a live broadcast of the daytime Weekly Dharma Assembly, followed by a meeting with the Jungto Society Standing 1000-Day Preparation Committee in the afternoon. In the evening, he will conduct another live broadcast of the evening Weekly Dharma Assembly.