May 1, 202 – Day 74 of 100-Day Dharma Talk , Heart Sutra Lecture 3, Buddhist Social Studies Course Lecture 16

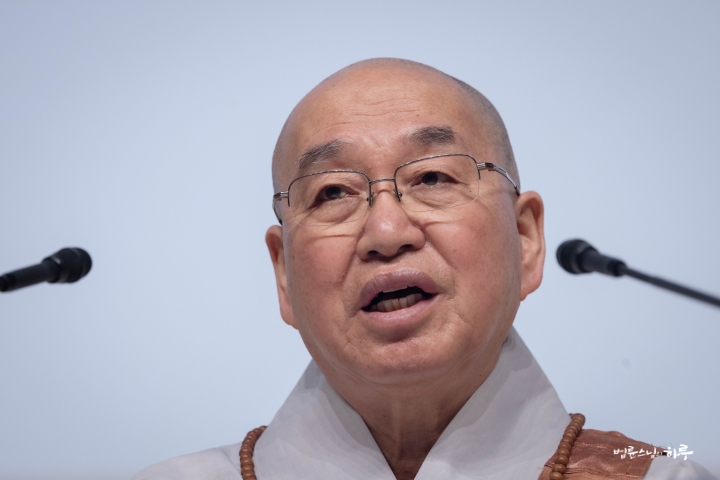

Hello. This is the 74th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today, there will be a sutra lecture and a Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to give the sutra lecture.

Today’s sutra lecture was moved from the third-floor Dharma Hall to the basement auditorium because it required audiovisual materials. About 110 people were seated in the basement auditorium, while approximately 560 people connected via online livestream. The audience requested the Dharma talk from Sunim with three full bows.

In the previous session, Sunim explained the first verse of the Heart Sutra in detail, and today he continued with the explanation of the second verse. Sunim emphasized that this verse contains the most essential content of the entire Heart Sutra as he began his Dharma talk.

Form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form. Form is emptiness, emptiness is form. The same is true for feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness.

“In our last session, we learned what it means when the Five Aggregates (五蘊) are all empty (空). The Five Aggregates refer to form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness (色受想行識). Today, we will discuss what it means when the first element, ‘form,’ is empty. The expression that form is empty is precisely ‘form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form’ (色不異空 空不異色), and ‘form is emptiness, emptiness is form’ (色即是空 空即是色). This is a type of logical proof. In logic, to prove that A and B are the same, we first prove that ‘if A, then B,’ and then prove that ‘if B, then A.’ This establishes that ‘A and B are the same.’ In other words, when the proposition ‘if A, then B’ is true, and its converse is also true, then A and B are the same.

Why the Five Aggregates Are Empty: The Logical Approach of the Heart Sutra

In Buddhism, what we call ‘I’ is considered to be composed of five elements: form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. The ‘self’ does not exist as an independent entity but is merely a collection of these five elements. This means there is no fixed entity that can be called ‘I,’ which is the concept of non-self (無我). In other words, the expression ‘there is no substantial self’ and ‘I am merely a collection of five constituent elements’ convey the same meaning.

In Hinayana Buddhism, while they accept the concept of ‘non-self’ (that there is no substantial self), they believe that each element that constitutes the self has its own substance. However, this position ultimately differs little from the view that a substantial self exists. It’s merely going one step deeper, but still essentially acknowledging the existence of a substantial self. This can be considered a non-Buddhist position that contradicts the Buddha’s teaching of dependent origination. The Heart Sutra criticizes precisely this aspect, stating that each of the Five Aggregates is empty. To logically explain that ‘form is empty,’ the sutra presents the perspectives of impermanence and non-self, because the law of dependent origination implies impermanence and non-self. Impermanence means ‘everything changes,’ and non-self means ‘everything is interconnected.’

Let’s first examine impermanence. Everything in this world is constantly changing. Traditionally, impermanence is explained in three ways. First, the material world goes through the stages of formation, existence, destruction, and emptiness. Second, the world of living beings experiences birth, aging, sickness, and death. Third, the mental world undergoes arising, abiding, changing, and ceasing.”

Sunim then explained how modern scientific discoveries—including physical changes, chemical changes, nuclear changes, the formation and destruction of stars, the Big Bang theory, the process of organic matter formation such as proteins and amino acids, and mental phenomena—support the teaching of impermanence. After that, he discussed the meaning of “form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form.”

Form Is Not Different from Emptiness, Emptiness Is Not Different from Form

“At the foundation of everything that exists in the world is matter. Life, too, is composed of matter. Mental activities occur on the basis of life. Therefore, matter, life, and mind are interconnected, and they all change. We may not recognize these changes because they happen either too quickly or too slowly. Due to these limitations in our perception, we sometimes mistakenly believe that certain things ‘do not change.’ However, in reality, nothing remains unchanged. This is impermanence. The principle of impermanence is expressed in the phrase ‘form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form’ (色不異空 空不異色).

When A changes into B, we cannot definitively say that A and B are the same, nor can we say they are different. Mahayana Buddhism explains this relationship with the concept of ‘not different’ (不異). It means ‘A and B are not different.’ This is a middle-way expression that neither claims they are the same nor different. Therefore, ‘form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form’ (色不異空 空不異色) means exactly that—form is not different from emptiness, and emptiness is not different from form. This sentence expresses the principle of impermanence as taught in Theravada Buddhism.

A World That Is Both Full and Empty: The Meaning of “Form Is Emptiness

The following phrase, ‘form is emptiness, emptiness is form’ (色即是空 空即是色), expresses the principle of non-self. For example, if we fill this hall with balloons full of air, we could describe the hall as both completely full and completely empty. From outside the balloons, the hall appears full, but from inside the balloons, it appears empty. Similarly, to human eyes, the Earth seems filled with matter, while space appears empty. However, from the perspective of subatomic particles, even the Earth is mostly empty space. The universe may appear empty to our eyes, but when viewed from an immense distance, it looks like a convex lens. Inside that lens are hundreds of billions of stars clustered together.

It’s not that the object itself changes to appear differently, but rather that how it appears changes according to my perspective, distance, and position from which I view it. From a distance, it appears as “form,” and up close, it appears as empty “emptiness.” Even closer, “emptiness” may again appear as “form,” and from further away, “form” may appear as “emptiness.” This is expressed as “is” (即是) because it’s a spatial concept rather than a temporal one. It means that something is simultaneously emptiness while being form, and form while being emptiness. This is precisely the meaning of “form is emptiness, emptiness is form” (色即是空 空即是色).

Thus, “form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form” (色不異空 空不異色) speaks of impermanence, while “form is emptiness, emptiness is form” (色即是空 空即是色) speaks of non-self. The former describes a temporal relationship, while the latter describes a spatial relationship. Having logically proven that form is empty and emptiness is form, it follows that form and emptiness are the same. In other words, form is indeed emptiness. In the same way, “feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness are also like this” (受想行識 亦復如是) expresses that “feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness” are also empty, just like “form.”

In the Heart Sutra, when it says “empty,” this can refer to “No Everlasting Abiding Dharma,” meaning nothing has a fixed nature; it can also mean “non-self,” indicating the absence of inherent existence; or it can mean “impermanence,” suggesting nothing lasts forever. One concept that contrasts with this idea of “emptiness (空)” is the concept of “form (相)” from the Diamond Sutra. Form refers to fixed concepts. For example, labeling someone as “a bad person” or something as “evil” is precisely what we mean by form.

My Husband Had an Affair, How Can I Overcome This Suffering?

However, in this world, there are no fixed forms, only relationships that form according to conditions at any given moment. Therefore, we must understand that all forms are non-forms, and recognize the emptiness of form. When we realize this, we have nothing to cling to. When we understand that there is nothing we can truly call “mine,” attachment to possessions disappears. It’s like discovering that what you thought was gold is actually just a gold-plated stone—there’s no reason to remain attached. The object itself remains unchanged, but your attachment vanishes. When attachment disappears, suffering ceases to exist.

Let’s assume your husband had an affair. Naturally, as his wife, you would be angry. But according to the teaching of impermanence, people’s minds are constantly changing. So what happened is simply something that could happen. Moreover, we can’t definitively say this event is bad. For example, if you were finding your marriage difficult and wanted to separate but lacked a reason, your husband’s mistake might actually be fortunate. This shows that events themselves are neither good nor bad. They only become good or bad according to our personal interests. If your husband was a good provider and treated you well, this affair would be deeply disappointing and infuriating because you’ve suffered both emotional and material loss. In other cases, you might even see it as a positive development. When you understand the true nature of reality, there is nothing to suffer about.

If your husband had an affair, you need to examine why it happened. You must find the cause and address it—suffering alone won’t solve the problem. If you only express anger, your husband might become more distant. When a problem arises, you should approach it from the perspective of how to solve it. You can either think, “I wanted to separate anyway, so this is good,” or “Separating would be disadvantageous for me.” Simply choose one of these two options. Understanding the emptiness of phenomena allows you to consider what decision is best in a changed situation. Saying things like, “How could you do this after the promises we made when we got married?” serves no purpose. That’s already in the past.

Everything changes according to causes and conditions; nothing remains unchanged. Nothing has inherent existence, and nothing is permanent. Even if someone is considered bad, they can transform into a good person at any time. Also, while the person remains the same, our evaluation of them can change depending on how we view them. If a husband helps his friends move every weekend, his friends might praise him as a ‘good person,’ but from his wife’s perspective, he might be considered a ‘bad person.’ Thus, these labels are temporary designations based on conditions, without any fixed essence. When you understand this reality, suffering disappears. This is the principle of emptiness in all phenomena.”

The passages that were difficult to understand due to their condensed classical Chinese expressions became easily comprehensible through Sunim’s various analogies. The lecture concluded just after midnight, with a promise to meet again.

Participants gathered in groups for mindful sharing, while Sunim moved to the basement dining hall to have lunch with the Sangha members.

At 1 PM, Sunim headed to the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Headquarters to deliver donations for forest fire disaster relief and cultural heritage restoration. A light spring rain had been falling in downtown Seoul throughout the day.

Upon arriving at the reception room on the 4th floor of the Korean Buddhist History and Culture Memorial Hall, Sunim was warmly greeted by Venerable Jinwoo, the President of the Jogye Order.

After exchanging greetings, Sunim immediately presented a donation of 100 million won for forest fire disaster relief and cultural heritage restoration.

Contributing to the Restoration of Temple Cultural Heritage Damaged by Forest Fires

After taking commemorative photos, they sat down for tea. Sunim expressed his sadness about the damage to temple cultural properties.

“We have collected these donations to help with the restoration of temple cultural properties, including Gounsa Temple, which suffered tremendous losses in the recent forest fires.”

Venerable Jinwoo expressed his gratitude.

“Thank you so much for gathering such generous donations. When I visited the site, it was truly devastating. Gounsa Temple was completely burned down, making it difficult to even identify its original location. Five temples were completely destroyed. The fire came within 1 kilometer of Bongjeongsa Temple, but fortunately, it was spared.”

The two continued discussing the dangers of forest fire damage. Sunim talked about measures to protect wooden structures.

“When wooden cultural properties like Bongjeongsa Temple burn down, even if they are restored, don’t they lose their national cultural heritage designation? Until now, we’ve only worried about fires starting from overturned candles in temples, but now forest fires are an even greater concern. The forests around temples have become too dense, so I think we need to better manage the surrounding woodlands.”

“You’re right. Gounsa Temple’s Yeonsu Hall and Gawunru Pavilion, which were designated as treasures, were wooden structures that completely burned down. Fortunately, fire-resistant covers played a crucial role this time. The high-performance ones can protect wood even at temperatures of 1000 degrees. They can prevent forest fires from spreading. Bongjeongsa Temple was fortunate as the fire only spread to within 800 meters. The Jogye Order has already provided financial support to affected temples and local residents in two phases. We’re also preparing to deliver emergency supplies worth 1.5 billion won, including food ingredients and home appliances, especially for residents who lost their homes.”

Sunim mentioned that JTS was also planning to provide basic seasoning sets including soy sauce, red pepper paste, and oil to 3,000 affected households in North Gyeongsang Province. They then shared positive assessments of the Jogye Order’s recent cultural approaches to introducing Buddhism to younger generations, as religious populations are increasingly aging. Everyone agreed on the need for the Buddhist community to reach out to new generations, recognizing these efforts as meaningful attempts to keep pace with changing times.

After taking commemorative photos with the President of Jogye Order, Venerable Jinwoo and presenting gifts, Sunim left the headquarters.

As the day drew to a close, at 7:30 PM, Sunim delivered the 16th lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course in the basement auditorium of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. About 180 people attended in person, while approximately 1,900 people connected online.

In the previous session, participants learned about the Buddhist perspective on socially controversial topics such as discrimination against sexual minorities, euthanasia, death with dignity, and abortion. Today’s lecture topic was “Why Should We Help Others?”

Sunim began the lecture by explaining how human conscience has developed.

“Today’s lecture topic is ‘Why Should We Help Others?’ Based on this theme, we’ll discuss how to approach the issue of helping others and to what extent we should help them. First, let’s examine basic human psychology.

The Conditions That Allow Humans to Be Called ‘Humanity’: Conscience and Good Nature

For example, imagine a one-year-old baby playing near a well. The child is crawling near the well and might fall in. Even a murderer or a thief who happens to witness this scene would find it difficult to just walk away. If the child repeatedly makes movements suggesting they might fall into the well, anyone would instinctively move the child to a safe place. Even if the child has no relationship with the observer, most people cannot simply pass by. Even a thief would prioritize saving the child. Even those who commit violence, steal, engage in sexual misconduct, use abusive language, lie, or live intoxicated have a deep unconscious psychology that ‘children must be protected.’

This is precisely what distinguishes humans from animals. If a cow were to pass by a well and see a child, it would not pick up the child with its mouth and move it to safety. This kind of behavior is a mental response unique to humans. This mindset is a natural psychological trait that all people possess, even without special education. We call this “conscience” or sometimes express it as “human nature.” The reason humans can have a conscience is not simply because we biologically belong to the human species, nor is it knowledge that comes from learning something.

How Can We Live a Fulfilling Life?

For us to be called human beings, two conditions are necessary. One is that we biologically belong to the human species, and the other is the existence of conscience as a mental function. The mental processes that humanity has developed while living in communities over many years are stored in the human brain and function like apps on a smartphone. These characteristics can be considered human nature. If someone lacks this conscience, we don’t view them as human and say they are “worse than beasts.” In other words, we see them as having lost their humanity.

However, humans don’t only possess conscientious functions. When overcome by anger, vengefulness, or attachment to gain, one might push a child at a well into it, or even throw a child who is playing happily in the yard into a well. Such behavior is not found in any animal other than humans. It is an unconscionable mental function that appears only in humans.

This mental function we call conscience is referred to as “good nature” or “seon-seong.” Negative mental functions such as vengefulness or selfishness are called “evil nature” or “ak-seong.” All these tendencies lie dormant in the human unconscious. When we examine which of these functions is more fundamental, we can see that good nature resides in the deeper foundation of the unconscious, while evil nature is positioned above it.

Modern psychology offers research supporting this view. In the early stages of a child’s ego formation, the mother does almost everything for the child. The child receives unconditional help from the mother, and this memory is stored in the unconscious like an app. This “mother’s mind” can be seen as our good nature. However, as the child grows a little older and begins to mature, the mother starts to scold the child, asking, “Why don’t you do as you’re told?” For example, “Why do you urinate anywhere? You should go in the designated place!” These demands begin to emerge. As these demands increase, the mental function of making demands also begins to sprout in the child. In other words, as the mother expresses desires and begins to make demands, the child likewise grows into a being who desires and makes demands. It is through this process that the child’s character is formed.

While humans inherently seek personal gain, they also possess maternal instincts. Maternal love is expressed when a mother finds great joy in nursing, caring for, and loving her child without expecting anything in return. Though parenting is challenging, there is fulfillment in the very act of giving love. This maternal mindset represents “maturity,” while its opposite—a childlike mindset—represents “foolishness.” When we extend this mature attitude to others, we experience genuine fulfillment and increased self-esteem. It is this mature consciousness in our subconscious that enables “unconditional giving.” Caring for neighbors as we would for children isn’t merely a biological instinct but the result of mental processes developed throughout human history. The joy we feel when helping others differs from the pleasure of satisfying our desires—it is “fulfillment.” This fulfillment forms the foundation of our self-esteem.

Stop Evil and Cultivate Good: Helping Others Is Practice

Those who are well-fed should help the hungry, the educated should help the uneducated, the healthy should care for the sick, adults should look after children, and the young should care for the elderly. These are good deeds. However, not doing these things doesn’t necessarily make someone bad. Bad actions include hitting, stealing from, sexually harassing, or bullying innocent people. Helping those in need falls into the category of good deeds. Not doing good deeds doesn’t make you a bad person, just as not doing bad deeds doesn’t automatically make you a good person. We must refrain from wrongdoing. The principle of “stopping evil and cultivating good” is called “ji-ak su-seon” in Korean.

If you want to live a more fulfilling life, it’s good to help others. Most people struggle because they don’t cultivate a helping mindset. Who suffers more—the beings who plead, “Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, please help me!” or Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva who is constantly helping others? We might think Avalokitesvara suffers more because of the endless work. What about Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva? After rescuing beings from hell, they should be grateful, but they often return to hell again. Ksitigarbha maintains the perspective that “their return to hell is their business; my business is to save sentient beings.” For practitioners, saving sentient beings is the path of their own practice. Those who practice with this perspective are called bodhisattvas.

Ordinary beings are prone to defilement. Hinayana practitioners avoid defilement, like the saying “White heron, don’t go where crows play,” so at least they refrain from wrongdoing. However, Mahayana bodhisattvas are like lotus flowers blooming in mud—they exist in the world while cultivating a giving mind. Thus, the thought of stealing doesn’t arise. Rather than forcing themselves not to steal, they actively cultivate a giving mind. This is why Mahayana bodhisattvas emphasize aspiration and vows, focusing on developing a helping mindset. In contrast, Hinayana practitioners emphasize following precepts and avoiding wrongdoing. The true path of a practitioner harmoniously combines both approaches. At minimum, we should refrain from harmful actions, and to the maximum extent possible, we should do good deeds. Instead of killing, we should save dying lives; instead of stealing, we should help those in need. This perspective is called “stopping evil and cultivating good.”

Helping others is like washing your own face with your hands. It’s not difficult. When you wash your face, your hands don’t say to your face, “Thank me for washing you.” Similarly, practice means seeing yourself and others as one, without distinction. This is called “great compassion of oneness” (dongche daebi). Rather than viewing it as “I am helping others,” adopt the perspective that “hungry people should eat, thirsty people should drink, and those without clothes should be clothed.” When sharing food with hungry children, saying “I’ll give you food if you believe in Buddhism” or “I’ll let you go to school if you believe in Buddhism” is not the right approach. Hungry people should naturally eat, and sick people should naturally receive treatment.

However, I cannot do all these things myself. If I become attached to the idea that I must solve everything, I’ll suffer from not being able to do it all. This means losing sight of the practice perspective. We should do as much as we can.

How have you been able to consistently help others?

Many people ask me why I help others. I can tell you that helping others is practice itself. My motivation for helping others came from seeing the situations firsthand. As Korea’s economy improved, we no longer routinely see people in difficulty within Korea. But when I went to India, I could see people who couldn’t eat, couldn’t go to school, and sick people everywhere on the streets. Also, as North Korea fell into famine, many refugees crossed into China. While traveling along the Yalu River, I saw many starved people who had died, emaciated children, and people begging. I think I started this work because I saw and experienced these things directly. I believe anyone who sees such situations directly would likely act similarly. Perhaps people’s hearts don’t move as readily when they only hear about these situations without seeing them. You might ask again, “How can someone maintain that commitment consistently once they’ve made it?” My answer is, “Because I continue to see those situations.” (Laughs)

I frequently visit developing countries. When I survey areas affected by floods, earthquakes, destroyed homes, and impoverished mountain villages, I experience two things. First, I become aware of how abundant and blessed my current life is. This awareness reduces my greed. Second, I feel tremendous fulfillment when I can provide even a small amount of help to those in need.

“When you have an extra 1 million won, is it better to spend it on nice clothes and delicious food for yourself, or to buy clothes for children who have none and provide meals for hungry children?”

When faced with this question, I find more fulfillment in giving clothes to children who have none and food to those who are hungry. If you agree, you can join in these activities. If you find more fulfillment in meeting your own needs, you can focus on your personal life. I don’t claim one approach is necessarily better than the other. I simply share what works better for me.

Five Principles of Humanitarian Aid to Provide Real Help

I follow several principles when engaging in relief work. First, I prioritize self-reliance. Helping someone simply because they are less fortunate than you doesn’t necessarily promote self-reliance. Self-reliance should be the fundamental principle for both ourselves and others.

Second, if someone is in a situation where they cannot be self-reliant, we should help them. If children cannot receive education at the appropriate time, if patients cannot receive treatment, or if people have suddenly experienced disaster, we should assist them. When people lack drinking water, food, clothing, medicine, or minimal shelter—when their right to survival is not guaranteed—this constitutes a humanitarian crisis. Verifying whether a situation is truly a humanitarian crisis must be our first priority.

Third, we must examine whether our help actually benefits the person in need. If someone intercepts our donations along the way, they provide no benefit. The process of confirming that aid reaches its intended recipients is called “monitoring.” Rather than simply assuming that what we give is received, we must ensure that effective systems are in place for delivery. For example, if I donate ten sets of clothes but only five are delivered because the other five disappear along the way, it would not be humanitarian to stop helping altogether. Such incidents occasionally occur during relief activities in developing countries. Of course, we should make every effort to ensure complete delivery. However, if even a portion reaches those in need, we should continue to help. We need to both increase the amount of aid and work diligently to improve the likelihood that our donations reach their destination. While poverty exists in many places, the degrees of poverty differ dramatically. In some places, people cry out because they cannot eat delicious food; in others, they cry out because they have no food at all. In some places, people lament not being able to afford a 3,000 won meal; in others, they cannot even afford a 100 won meal. Though both situations are described as “poverty,” we should prioritize helping those in more dire circumstances.

Fourth, we must always consider whether our assistance might undermine self-reliance. This is similar to fertilizing a field—while fertilizer helps crops grow better, excessive amounts can cause overgrowth and death. We should not provide help that hinders self-reliance. Conversely, simply leaving people alone doesn’t guarantee they will become self-reliant. Extreme poverty can make self-reliance impossible. We should provide appropriate assistance that enables self-reliance. Excessive help that results in overprotection can actually harm self-reliance. This is because our satisfaction is not the goal—what matters is whether we’re providing genuine help.

Humanitarianism: Looking Beyond Barriers to See the Suffering

Fifth, many barriers exist when helping others. National boundaries create one such barrier, restricting entry to our country. Sometimes people intercept and take items during the delivery process. When faced with such barriers, most people stop helping. However, we must look beyond these barriers to see the people in need. Especially when helping North Korean citizens, we should focus on the people, not the officials. If we focus on the officials, we lose all desire to help due to negative feelings. Therefore, when helping others, we must develop the ability to see beyond barriers rather than stopping at them.

When helping others, we should not consider race, gender, religion, or political systems. We should only look at whether they are starving. We shouldn’t distinguish between South Koreans, North Koreans, Muslims, or Buddhists. The principle of humanitarian aid is maintaining this perspective. Of course, reality often differs. People resist: “Why help foreigners when there are so many poor people in our own country?” “Why help North Koreans?” “The food we provide will come back to us as bullets.” “Why help Muslims who destroyed Buddhist statues?” I understand these concerns. However, humanitarian aid means overcoming such resistance to help those in need.

Today’s session focused on Buddhism and welfare, the socialization of compassion, principles of aid, and the importance of volunteering. The next session will cover “Climate Crisis and Stopping Consumption.”

Participants shared their thoughts in small groups, and Sunim returned to the Jungto Center to conclude his daily activities.

Tomorrow will be the 75th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will conduct a Friday Dharma Q&A session for the daytime group at the main hall of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. In the afternoon, he will travel to the National

Assembly to deliver congratulatory remarks at a forum on “K-Democracy and Peace on the Korean Peninsula.” In the evening, he will conduct another Friday Dharma Q&A session for the evening group.