Apr 19, 2025 – 62nd day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Jungto Dharma School Q&A

Hello. Today is the 62nd day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk.

In downtown Seoul, the cherry blossoms have fallen, and fresh green leaves have begun to sprout abundantly on the street trees.

In the morning, a 1080 prostration practice was held in the Dharma Hall on the third floor of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. About 150 people participated, chanting Buddha’s name vigorously and prostrating in rhythm with the moktak wooden instrument.

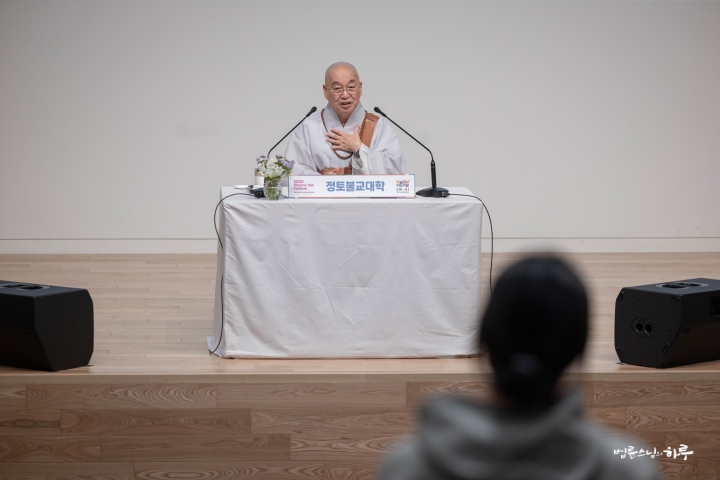

After lunch, Sunim headed to the basement auditorium to meet with Jungto Dharma School students. At 2 PM, the Dharma Q&A session began with the recitation of the Threefold Refuges and Words for Practice.

This semester’s Jungto Dharma School is being conducted alongside the 100-Day Dharma Talk, with approximately 2,000 students divided into three groups: in-person, live broadcast, and basic course. Students who had previously only attended online classes were given their first opportunity to meet Sunim in person and ask questions directly.

Before beginning the dialogue, Kim Ra-gyeol, a youth volunteer at Jungto Society, energetically sang the song “Cherry Blossom Ending.”

After listening to three students share their impressions of the course, everyone together requested Sunim’s teaching with three bows. Sunim briefly explained the purpose of this lecture and then immediately began the dialogue.

“Today is an opportunity to share questions that have arisen during your Buddhist studies so far. Originally, I had planned to lecture for 70 minutes in each class and then spend 20 minutes addressing questions, but I haven’t managed my lecture time well, so we haven’t had many opportunities for questions. That’s why I’ve set aside this time specifically for questions, like a supplementary class. Now, please ask anything you’d like.”

Eight people raised their hands to ask Sunim questions. One person sought Sunim’s advice about frequently receiving burdensome requests from others, wondering whether to continue accommodating these requests or to firmly refuse them.

Can I refuse a request that I’ve been accommodating out of fear the other person might get angry?

“There’s no absolute right or wrong here, so you can do whatever works best for you. If you don’t want to do what someone is asking, you can simply say, ‘I won’t do that,’ and not do it. If this becomes a problem and you get fired, you can move to another company. If the other person yells at you, you can just accept that ‘this person is yelling.’ It’s their health that suffers from getting angry, not yours. However, if refusing their request would result in losing your job and that would be more detrimental to you, then you might choose to comply even if you don’t want to. Conversely, if accommodating their demands causes you so much stress that you become ill, then it’s better not to do it. You should weigh which option benefits you more and be willing to give up the other. Consider everything in relation to your own benefit. In any situation, choose the direction that maximizes your benefit. The ‘benefit’ I’m referring to isn’t just economic—your emotional well-being, whether you feel good or bad, is also part of this broader concept of benefit.

We are already living by weighing economic benefits and stress levels in every situation before making judgments and decisions. You too are likely sometimes accommodating others’ requests and sometimes refusing them. You might think, “Should I just refuse it?” but then decide, “That would only hurt me,” and move on. So there’s no need to ask this question anew—we’re already living by calculating according to our own standards. Take marital arguments, for example. Even when a wife is upset by her husband’s words, she often holds back for the sake of the children or the household atmosphere. Then when she can no longer tolerate it, she occasionally explodes. This decision to either endure or express anger ultimately comes down to calculating “which option offers better profit and loss.”

When you become aware that you’re already making judgments based on profit and loss calculations, your stress decreases. Many of our reactions are driven more by profit and loss considerations than by personality. It’s not that you endure because you have a good personality; you endure to avoid loss. When someone bursts out in anger and you respond with anger too, you’re accepting a loss. As the saying goes, “When angry, you can’t see anything else,” and after angrily lashing out, you later regret it when it turns into a loss. Then you endure again until something triggers your anger once more, repeating the cycle. This happens because in that moment, you believe that expressing anger is emotionally more beneficial than enduring it. In other words, even when you anticipate a loss, you express anger because you think it will make you feel better. Thus, we constantly weigh benefits against losses as we go through life.

When you’re not fully aware that you’re living a certain way, you might wonder, “What should I do?” However, once you realize that you’re already making decisions based on profit and loss, your mindset changes. For example, you might calculate in advance whether to get angry or not, and if the consequences seem more harmful, you’ll hold back. This restraint isn’t for the other person’s benefit but for your own advantage. Conversely, when you do express anger, you’re accepting the resulting losses. In that moment of rising anger, your judgment becomes clouded, and you end up causing yourself harm. This is why regret follows afterward. In such situations, if you think, “I’m holding back for the other person’s sake,” you’ll actually experience more stress. Instead, it’s easier to think, “Everyone is simply living according to their own temperament.” It’s better to consider it lightly: expressing your temper leads to loss, while restraint reduces that loss.

Buddha’s teaching takes this one step further. True wisdom is not about restraint but about accepting people as they are, thinking, “That’s just how they are.” This way, you neither suffer losses nor experience stress. When we get angry, we lose; when we hold back to avoid loss, we become stressed. As stress builds up, we eventually explode, then suffer losses, then hold back again—repeating this cycle endlessly.

Neither expressing anger nor suppressing it is a good approach. Buddha saw people as they were: “That person has a quick temper,” or “That person tends to burst out in anger.” The same applies to you. When someone rushes you, simply acknowledge, “This person always hurries others,” and then proceed at your own pace. When dealing with someone who explodes in anger, if you’ve already recognized, “This person has a tendency to flare up,” you can respond without fear.”

“In a workplace, if I don’t like it, I can simply leave. But relationships with parents aren’t always that simple. How should I respond to my parents’ demands?”

“Moving out solves the problem easily. It might even be simpler than leaving a job. With a job, your salary is at stake, but when you move out of your parents’ home, you’re just paying extra for rent. Since you should be independent after turning twenty, this isn’t a major issue. If you can accommodate your parents’ wishes, do so. If you absolutely cannot, simply move out and live separately. However, if you’re living in your parents’ home and eating the meals they provide, you must pay the price for that. If you can’t repay them with money, you should repay them by being obedient. You should accept their demands and nagging as natural. If you were living rent-free in someone else’s house and getting free meals, you would be grateful even if the homeowner nagged you. But with parents, we think ‘they’re my parents, so it’s expected,’ which is why we perceive the same words as stressful. Try thinking of your parents’ home as someone else’s house. Then, no matter what your parents say, you’ll feel grateful instead. Imagine if you borrowed $100,000 from someone, and they said, ‘I’ll reduce it by $10,000 each time you let me slap you.’ Would you be angry about being slapped? No, you’d be so happy you’d ask them to slap both cheeks.

The Buddha’s way of viewing the world is expressed as ‘gwan (觀)’ or ‘jogyen (照見)’. When applied to daily life, these concepts can reduce conflicts both large and small. ‘Gwan (觀)’ means observing others as they are without judgment, while ‘jogyen (照見)’ refers to the attitude of insight that deeply penetrates a person’s inner self and their circumstances. When we can see facts as they are, unnecessary conflicts and misunderstandings naturally decrease. For example, when you start working at a company, you should first understand the people and the atmosphere. Adapt to what you can, and for what’s difficult to adapt to, ask questions and learn. If someone criticizes you for not adapting, simply respond with “yes” and accept it. Do what you can, and when you can’t, just say “I’m sorry.” If someone criticizes you saying, “You’re all talk,” respond humorously with “Yes, at least my mouth is working.” However, when you’re too attached to yourself, responding this way becomes difficult. If conflicts arise even with parents who gave birth to and raised you, how can you avoid clashes with colleagues?

Speed in completing tasks doesn’t have an absolute standard. If someone works faster than you, they will naturally perceive you as slow. So being urged to work faster is natural. When you accept that others will inevitably feel this way, the situation becomes much more comfortable.

All people are different from one another. Some are faster than me, some are slower than me, some are more meticulous, and others are more casual. Therefore, instructions must vary accordingly. Phrases like “don’t rush,” “hurry up,” or “be more thorough” ultimately come from each person’s own standards. This doesn’t mean you should change others’ standards or adjust your own. What’s important is being self-aware of your own standards and tendencies. Whether you tend to be hasty, relaxed, harsh in speech, or excessively meticulous—simply knowing this is enough. Without this awareness, when someone expresses dissatisfaction with you, you’ll first feel wronged or hurt. However, if you recognize your natural tendencies, you can take others’ reactions more lightly, and your relationships will become much more comfortable.”

“If I’m too slow to match someone’s pace, should I just accept that I’ll be scolded?”

“Rather than thinking you’ll accept being scolded, it’s better to understand, ‘According to their standards, it makes sense that I would be scolded.’ Don’t worry about whether you’ll be scolded or not—just accept the situation as natural. Someone with an impatient personality will naturally rush or get irritated when things don’t meet their standards. If you anticipate this, even when you are scolded, it won’t upset you much. You might even think, ‘That’s strange, they’re not scolding me today.’ If possible, it’s good to try matching the pace of faster people to some extent, as long as it doesn’t burden you. However, if trying to keep up makes you anxious and harms your health, then you should let others know about your situation.

‘I’m trying to keep up, but I simply can’t match the pace. I’m always feeling anxious and uneasy. Please understand if I’m a bit slower.’

This is how you inform others. We call this ‘notification.’ You’re not saying the other person is wrong or complaining about them—you’re simply informing them of your situation. Hoping others will understand without saying anything doesn’t help at all.”

“Thank you. I understand now.”

The questions continued.

Some people work tirelessly yet struggle to buy a home, while others easily inherit one. Why do some people fail to get what they desperately want, while others easily obtain what they desire?

If Buddhism teaches “non-self,” is the effort to find one’s self meaningless?

Though I understand the law of dependent origination intellectually, when I get angry, how can I genuinely accept the other person?

How can I accept life as it is and remain unwavering when my mind fluctuates despite intellectually understanding Buddhist teachings?

Within the teaching of not making judgments, is discerning right from wrong still necessary in daily life?

The final questioner asked Sunim how to maintain a life of restraining desires.

How Can I Maintain a Life of Restraining Desires?

“By suppressing desires through determination and resolution, you may become a good person who doesn’t harm others. However, suppressing your mind this way can easily lead to stress. When you don’t follow your desires, you avoid losses, but instead, you experience stress. As stress accumulates, there’s a risk that desires might burst out at some moment due to stimulation. Living with such risk might be a second-best option, but from a practice perspective, it’s not the optimal solution.

Rather than constantly suppressing your desires, it’s better to practice mindfulness. Whether it’s sexual desire or gambling urges, instead of gritting your teeth and enduring, simply notice, “Ah, desire is arising.” Don’t follow the desire, but don’t condemn it as sinful either. Just acknowledge, “I have this desire.” For example, when sexual desire arises, it will gradually subside as time passes. The same applies to other desires. When trying to quit smoking, if you repeatedly make resolutions like “I must quit smoking!” only to start again, you eventually lose trust in yourself and your self-esteem drops. Instead of forcefully suppressing the urge by thinking “I shouldn’t smoke,” simply acknowledge, “I notice I want to smoke.” With time, that desire will gradually subside. No desire persists indefinitely.

When you follow the desire to smoke by actually smoking, you temporarily satisfy that craving. It’s like feeding the desire. When desire is fed, it becomes quiet for a while, but when hunger returns, the desire resurfaces. Since you need to feed the desire, you smoke again, and this cycle continues. What happens if you acknowledge the desire to smoke but don’t feed it? Will the craving for cigarettes persist? No, it won’t. After a certain period, the desire for cigarettes will naturally subside even without smoking.

Whether you smoke or not, desire doesn’t persist continuously. It subsides temporarily and then rises again in a repeating cycle. When desire arises, if you spend a little time in mindfulness, the desire naturally subsides. Then, as time passes, desire arises again. Whether you smoke or not, this phenomenon of desire arising follows the same pattern of repetition.

Whether you smoke or not, the cycle of desire arising and disappearing repeats, but the intervals and intensity gradually change. If you follow your desire and smoke, that desire becomes stronger with each repetition. Conversely, if you don’t smoke, the intensity of the desire gradually weakens over time. To use an analogy, if you continue to feed your desire, it gradually strengthens; if you don’t feed it, it slowly weakens. After practicing for about ten days, it becomes easier to free yourself from desire because its intensity progressively weakens compared to when you first started. To move in the direction of gradually becoming free from desire, you need to continue practicing mindfulness.

However, there are aspects of desire that we can control, and there are others, like hormonal secretions, that are physical processes difficult for us to regulate. For example, with sexual desire, the intensity varies from person to person. Some people feel it more strongly than average, while others feel it less intensely. Among them are those who cannot control themselves. In such cases, it’s advisable to visit a hospital and consult with a doctor. Sometimes these issues arise due to excessive hormone secretion. If the situation exceeds your ability to control, it could potentially lead to criminal behavior, which is why treatment is essential.

Therefore, punishment alone is not the solution for crimes. For instance, someone who feels sexually intimidated by adult women but approaches children may easily commit child sexual abuse. This can also be considered a psychological disorder. Rather than focusing solely on punishment, we should ensure that appropriate treatment is available through medical care. The same applies to drug or alcohol addiction. Some people, once they start drinking, cannot control themselves—that’s addiction. No matter how much others tell them to stop drinking, they cannot regulate themselves. Those who cannot exercise self-control need medical treatment or isolation therapy. The same goes for drugs. Once addicted, it’s difficult to quit alone, no matter how determined one is. Nowadays, there’s an increasing number of young people with weak mental self-control. When such individuals are exposed to drugs, it becomes extremely difficult for them to control themselves.

Therefore, rather than just enduring, one should practice mindfulness, and when this proves difficult, it’s better to check your condition at a hospital instead of merely making resolutions. Physical issues are very difficult to overcome through determination alone, but they can be easily resolved with proper treatment. If you examine these two aspects, you will be able to live a healthier and more liberated life than you do now.”

“Yes, thank you.”

After 4 PM, Sunim concluded his lecture. The students continued their mindful sharing in small groups.

Since many students were visiting the Jungto Social and Cultural Center for the first time, they took a tour of the facility in groups. On the second floor lounge, various booths were set up offering different experiences such as sewing workshops and lantern making.

As the sun set, Sunim handled various administrative tasks in his office before concluding his day.

Tomorrow will be the 63rd day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will conduct a meditation retreat in the Dharma Hall on the third floor of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. In the afternoon, he will attend the 80th anniversary celebration of Kyungdong Church and deliver a commemorative lecture.