Apr 14, 2025 – 57th Day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk, Sutra Lecture·Buddhist Social Studies Course 11th Session

Hello. This is the 57th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today features both a sutra lecture and a Buddhist Social Studies course. A gentle spring rain has been falling all day in Seoul.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to deliver the sutra lecture.

About 110 people gathered in the third-floor Dharma hall, while approximately 560 people connected via the online livestream. After the audience offered three bows to request the Dharma teaching, Sunim ascended the Dharma seat.

Today marks the eleventh session of the Diamond Sutra lectures. In the previous session, Sunim covered up to Chapter 23 of the Diamond Sutra. Today, he continued with his explanation from Chapter 24 through Chapter 29.

“Chapter 24 of the Diamond Sutra, ‘Incomparable Merit and Wisdom,’ explains that merit and wisdom are beyond comparison. This means that giving without attachment to appearances generates immeasurable merit compared to giving with attachment. In other words, if you act without distinguishing between ‘me,’ ‘you,’ or ‘us,’ the merit is boundless. No matter how much you give in a dream, once you wake up, it was merely a dream. Even offering a single bowl of water after awakening generates greater merit than offering the seven treasures as large as Mount Sumeru in a dream. Dreams are just dreams. Once you wake up, nothing has happened.”

After explaining Chapter 25, Sunim moved on to Chapter 26.

“Next is Chapter 26, ‘The Dharma Body Is Not a Physical Form (法身非相分).’ Here we find the famous four-line verse of the Diamond Sutra:

Buddha refers to the awakened one. This verse means that we should not seek the Buddha through form, sound, smell, taste, touch, or thought. We can reach enlightenment only when even thinking stops. Everything conceived by thought is merely an illusion. That’s why it’s called ‘The Dharma Body Is Not a Physical Form(法身非相).’

Next, Sunim read and explained Chapter 27, “Neither Annihilation Nor Permanence.(無斷無滅分)”

People tend to think there are fixed dharmas that are ‘the truth,’ so the Buddha, to break this attachment to appearances, said, ‘There are no fixed dharmas.’ We should then realize, ‘There are no fixed dharmas; everything arises according to causes and conditions.’ But then people become attached to the idea that ‘there are no fixed dharmas.’ When attached to this view, they begin to claim, ‘There is no truth.’ This perspective is called ‘annihilationism(斷見).’ The view that there are fixed dharmas is called ‘eternalism(常見),’ while the view that there are no fixed dharmas is called ‘annihilationism(斷見).’ Because people were attached to the idea that ‘things exist,’ the Buddha broke that attachment by saying ‘they don’t exist.’ But when people became attached to ‘non-existence,’ he had to break that attachment by saying, ‘You can’t say they don’t exist either.’ The Middle Way is to transcend the appearances of ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence.’ The Middle Way is not the middle between this and that, but the path that transcends both. Do you understand? Looking at your expressions, it seems you don’t quite get it. (Laughter)

Since the core teaching of the Diamond Sutra is “No Everlasting Abiding Dharma” (無有定法), which states that there is no fixed law, the question arises: “Does this mean we can do whatever we want?” When someone asks for directions to Seoul and the Buddha replies, “There is no fixed path to Seoul,” this doesn’t mean “You can go any way you want.” Nor does it mean “There is no path.” Yet we tend to interpret this either as “There is no path” or “There are countless paths.” However, “No Everlasting Abiding Dharma” means neither “nothing exists” nor “infinite possibilities exist,” but rather that everything arises according to causes and conditions. For someone in Incheon, the path to Seoul is eastward, while for someone in Suwon, it’s northward—the direction is determined by one’s circumstances. Therefore, when someone from Incheon asks for directions to Seoul, the answer shouldn’t be “There is no path” or “Go any way you like,” but rather “The path to Seoul is east!” This way, there is no discontinuity (無斷) or cessation. People tend to cling to existence (有), so existence is negated; then they cling to non-existence (無), so non-existence is negated. Because we constantly cling to permanence, impermanence is taught. And when we cling to impermanence, we are cautioned against this attachment through the teaching of “no discontinuity and no cessation” (無斷無滅).

The Middle Way Is Departing from the Notions of ‘Existence’ and ‘Non-existence’

The view that something “exists” is called eternalism (常見). The view that something “does not exist” is called nihilism (斷見). We constantly cling to the notions of “existence” and “non-existence.” We often debate whether something always exists or not, but regarding God, it is incorrect to say either that God exists or does not exist. This is because whether God actually exists or not cannot be objectively stated. It is a matter of faith and perception. For those who believe in their hearts that God exists, God does exist; for those who believe God does not exist, God does not exist. Since it is a matter of belief in the mind rather than an objective discussion of reality, it is not a question of existence or non-existence outside the mind.

Let’s say there is a cup here. What does “existence” mean? The cup exists because I perceive it. But if I move farther and farther away from this cup until I’m viewing it from space, would the cup still exist? If it cannot be perceived, it would disappear. Conversely, if I become smaller and smaller and look at this cup from the perspective of a subatomic particle, would it exist? It would not be perceived and would appear like empty space. Therefore, something can be perceived as existing only when viewed from an appropriate position.

The same applies to light wavelengths. If the wavelength is too short or too long, I cannot perceive it. I can only perceive wavelengths within a certain range. We tend to think that what we perceive exists, and what we cannot perceive does not exist. Therefore, existence and non-existence are not matters of reality but matters of perception. The correct way to express this is to say, “This is how I see it,” “According to my understanding,” or “In my opinion.”

War and Conflict Stemming from a Judgmental Mind

If someone argues, “The impeachment should be upheld” or “The impeachment should be dismissed,” regardless of right or wrong, we should view it as “This person thinks this way” or “That person thinks that way.” Such a person is neither particularly bad nor particularly good—they are just like me, only with different thoughts. Why do we have different thoughts? Because we have different information or different beliefs. Therefore, we should not be obstinate about anything. We should not condemn others’ thoughts or beliefs. Throughout history, all misfortunes have stemmed from a judgmental mind. Killing people for not performing ancestral rites or for not believing in God—these are all forms of condemnation. The wars and conflicts occurring around the world today all stem from a judgmental mind. We must acknowledge our differences.

When we propose sending food to help starving people in North Korea, the right-wing opposes it, claiming North Korea is our main enemy. In this view, even North Korean civilians become enemies. They interpret helping North Koreans as aiding the enemy and condemn such actions as pro-North Korean or communist. Some North Korean residents, unable to endure hunger, cross the Tumen or Yalu River into China. However, they face the same starvation in China. When we try to help them, North Korean authorities oppose it, calling these people traitors who abandoned their nation for self-preservation. This is how things appear when viewed from a single perspective. Whether inside or outside the border, whether they’ve come to South Korea or gone to China, people who cannot eat are simply people in need of help. We should help those inside from inside, and those outside from outside. That’s why Jungto Society operates on the principle of helping hungry people regardless of ideology.

When we form fixed views, we antagonize and criticize others. Everyone forms views according to their convenience, so from their own perspective, everyone is right. We cling to our views, and it’s not easy to let them go. We can only release our attachments by leaving our comfort zone. As long as we don’t leave our comfort zone, no matter how much we study or think, we cannot erase the subconscious belief that we are right. That’s why we cannot become free. Those who are attached to money may let go of everything else but cannot let go of money. Those who are attached to ideology may let go of everything else but cling to their ideology. Of course, some people cannot let go of anything. If there’s just one thing you cannot let go of while releasing everything else, that attachment is extremely strong.

Nothing Is Absolute, Everything Is Relative

That is why we must transcend the notions of “exists” and “does not exist.” In times like these when the nation is divided, when I say “we should move beyond right and wrong,” many people object, asking, “If there is no right or wrong, how can we punish those who support rebellion?” Originally, there is nothing that can be deemed absolutely right or wrong. Right and wrong are formed according to causes and conditions. Nothing is absolute; everything is relative. Everything comes into being through interdependent causes and conditions.

The Buddha’s teaching is that there is nothing absolute in this world. However, in the world we live in, there are areas where ethics and precepts are necessary. Therefore, it is better for precepts to have as much universality as possible. We need to move beyond a human-centered perspective. We must stand from a viewpoint that establishes human ethics based on ecological ethics, taking nature into consideration.”

After explaining the 28th and 29th minutes, Sunim concluded the lecture.

The participants gathered in groups for mindful sharing, while Sunim moved to the dining hall on the first basement floor to have lunch with the community.

In the afternoon, Sunim took care of office work and prepared for the Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture.

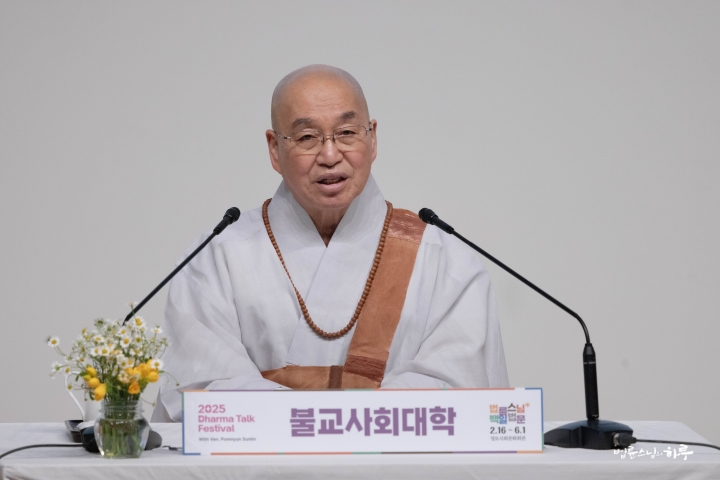

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim delivered the 11th lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course in the main hall of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

In the previous session, there was a special lecture on “How to View the Presidential Impeachment Issue from a Middle Way Perspective.” Today, Sunim began the lecture with the topic “Is Buddha a Seeker of Truth or a Revolutionary?”

“Today’s lecture topic is ‘Is Buddha a Seeker of Truth or a Revolutionary?’ What is the difference between a ‘seeker of truth’ and a ‘revolutionary’? A seeker of truth is someone who makes new discoveries or raises questions about existing ideas. If one simply follows existing ideologies or social orders, they might be called a scholar or thinker, but not a seeker of truth. A seeker of truth breaks down existing thoughts and concepts and raises new questions. In other words, a seeker of truth is someone with a strong exploratory attitude. In contrast, a revolutionary is someone who proposes issues that transcend the existing social order or system itself—a complete social transformation—and puts them into practice. Of course, if one seizes power through force, that is merely a coup d’état, simply a seizure of power.”

Sunim then explained in detail what Indian society was like during Buddha’s time. This was necessary because understanding the social background helps determine whether Buddha was a seeker of truth or a revolutionary. After describing how severe class discrimination and gender discrimination were in Indian society at that time, Sunim continued with the explanation.

Why Can We Call Buddha a Revolutionary?

“In such an era, Buddha’s life first had the character of a seeker of truth. Buddha did not become a great person by following existing teachings. He questioned traditional thought and entered as an emerging thinker, but his questions remained unresolved. So through repeated exploration, he presented a new path on his own. This has a strong character of seeking truth. He discovered a new method of practice called the Middle Way and finally attained enlightenment. The content of this enlightenment is the law of dependent origination. The law of dependent origination states, ‘Because this exists, that exists; when this ceases to exist, that also ceases to exist.’ He discovered that everything arises according to causes and conditions and disappears according to causes and conditions. However, traditional thought until then was based on permanence and believed in the existence of a permanent self. The law of dependent origination shook these existing traditional thoughts to their roots. The Middle Way means not being biased toward anything. It means embracing the world while walking a new path, and embracing the existing while walking a new path.

A Revolutionary Who Transcended Both Class and Gender Discrimination

Everything that is formed will eventually dissolve. Suffering itself does not inherently exist but arises due to causes and conditions, and therefore can disappear according to causes and conditions. This was a revolutionary concept in an era dominated by deterministic thinking. At that time, people believed everything was predetermined—either by God, by past lives, or by fate and fortune. The Buddha rejected all these deterministic views. He taught that karma is not an innate destiny but something that is formed, and therefore can be changed and eliminated. This teaching of the Buddha was essentially a complete rejection of the existing philosophical paradigms. Being noble or common is not something one is born with, but rather something created by our consciousness. In the sutras, the Buddha uses various analogies to illuminate this truth. If we abandon such consciousness, existence is simply existence. This is what we call “equality.” In this way, the Buddha rejected class discrimination in practical reality.

At that time, masters could renounce the world, but slaves could not. This was because one needed to have autonomy over one’s own life to become a monastic. If a slave secretly ordained, the master would recapture them, considering it a loss of property. However, Buddha accepted Upali, a barber by profession, thereby acknowledging the ordination of Sudras, who were slaves at that time.

Women were also not allowed to renounce secular life in those days. However, many women of the Shakya clan had lost their parents, and their husbands and children had become monastics. In those times, women lived by the principle of “three obediences” – obeying their father when young, their husband after marriage, and their son after their husband’s death. Therefore, for a woman to renounce secular life meant liberation from being bound to someone else. This is why the women of the Shakya clan stepped forward saying, “We also want to renounce secular life.” According to the social conditions and customs of that time, this was impossible. Nevertheless, Buddha recognized women’s right to ordination. Renunciation is the path to becoming the master of one’s own life. Buddha had already achieved both class liberation and gender liberation 2,600 years ago.

However, the Buddha was unable to eliminate caste discrimination throughout society. Nevertheless, within the Buddha’s Dharma, everyone was equal. That is why he said:

‘Just as there are four rivers in the world that become one when they reach the sea, there are four castes in the world, but in my Dharma, they are one.’

This was revolutionary in Indian society at that time, where caste and gender discrimination were severe. The Buddha told Nidai, a toilet cleaner, “Just as clothes stained with excrement become clean when washed, although you are called an untouchable, you too are inherently pure when freed from ignorance.” Nidai shed his false consciousness of being an untouchable and became a practitioner. The same applied to Culapanthaka, who couldn’t memorize even a single sentence. Cleaning is about removing dust and washing away dirt, isn’t it? The Buddha instructed Culapanthaka to keep repeating, “Remove the dust and wash away the dirt.” Eventually, Culapanthaka became aware of his own mind and attained enlightenment. In this way, the Buddha taught the Dharma according to each person’s level, enabling anyone to attain enlightenment.

Looking at these aspects, the Buddha can truly be called a revolutionary. From an ideological perspective, he can be considered a seeker of truth. Furthermore, the Buddha went beyond being a seeker to become a revolutionary who rejected the caste discrimination and gender discrimination that were the social order of his time.

The first precept taught by the Buddha is non-violence. It means not using force to get what you want. Therefore, the Buddha did not try to eliminate caste and gender discrimination by mobilizing power. However, he didn’t just stop at making claims but actually realized these principles within the boundaries of the Sangha. What we need to do today is to spread the model created by the Buddha and implement it throughout society. Even though times have changed, there isn’t anything particularly different that we need to do. The Buddha’s teachings remain revolutionary even by today’s standards. If we neglect to spread these teachings, we could say there has been no progress even after 2,600 years. If we still accept discrimination today, we have actually regressed.

The Life of a Practitioner Who Never Kept Servants

Before renouncing the world, the Buddha lived with numerous servants who took care of his household, drove his horses, prepared his food, and performed various other tasks. However, after becoming a monk, he never kept servants until his death. In Korean history, the Silla period was both a class-based and agricultural society. At that time, the greatest assets were, first, land, and second, slaves. Therefore, when victorious in war or when rewarding someone, land and slaves were often given. The nobility lived with personal attendants serving at their side. However, the Buddha did not live within such a system after his renunciation until his passing into nirvana. The same was true for all monks who renounced during the Buddha’s time. However, during the Silla period, when kings gave land and slaves to temples, monks lived based on those resources. Master Uisang did this, Master Jajang did this, and most monks based their lives on this system to study and become great scholars. Therefore, they can be called great scholars but not great seekers of truth.

Today, all temples employ workers to support the monks’ lifestyle. We can view this as the evolution from slaves in ancient slave societies to serfs in medieval times, and now to workers in our capitalist society. If you visit any temple, you’ll find separate people who cook, drive, and clean. Even if you visit temples in Southeast Asia, you’ll see monks living on this foundation. Temples exist on the foundation of the capitalist system. The only way monks distance themselves from social norms is by not marrying. Apart from a few such exceptions, they are fundamentally within the capitalist system.

If Workers Were Hired to Do Certain Tasks…

However, Jungto Society carries out all its activities through volunteering to avoid hiring workers. In this respect, Jungto Society operates inefficiently in this capitalist society. Although volunteers share roles to manage everything, it is actually not easy to maintain. It’s possible when the scale is small, but as the organization grows, difficulties arise.

Thus, the Buddha was someone who transcended the existing social system. The Buddha lived 2,600 years ago when society was based on a caste system. However, he was not constrained by that social system. Today, we are under a capitalist system, so we are inevitably influenced by it. If someone from the next stage, from outside the capitalist system, were to evaluate us now, how would we be judged? We would likely be assessed as not much different from those who couldn’t escape the limitations of the caste system during the Joseon Dynasty. If Jungto Society were to hire workers for its activities, it would not be transcending our era. We might only be evaluated as people who did somewhat good deeds within our time. In this respect, wouldn’t you say that Buddha was both a great seeker of truth and a great revolutionary?

Jesus’ life also had the characteristics of both a truth-seeker and a revolutionary. However, the difference is that Jesus’ life ended in martyrdom due to social resistance. In contrast, Buddha carried out a fundamental revolution, but his method was non-violent. He chose to awaken people’s consciousness. Of course, there were many difficulties, such as the annihilation of the Shakya clan and the murder of disciples like Angulimala and Maudgalyayana, but Buddha himself was not killed. Later, as the Dharma was transmitted to future generations, Bodhidharma, who brought Buddhism to China, was killed because of his radical approach, and the Second Patriarch, Huike, was also murdered.

This is the revolutionary life that Buddha lived. Buddha was not a god but a human being—a great seeker of truth and a teacher among humans. That’s why I wrote the book ‘Human Buddha: His Great Life and Thought.’ When I gave lectures on this topic for EBS, they titled it ‘Buddha the Revolutionary.’ That’s how today’s lecture topic became ‘Buddha the Revolutionary.’

After speaking about the Buddha’s life and philosophy for an hour and a half, Sunim took questions from the audience. Three people raised their hands to ask questions on the spot. One of them mentioned that while Jungto Society operates on a volunteer basis to overcome the limitations of capitalism, there is also a need for professional staff, and asked what the Middle Way would be in this situation.

It’s Difficult to Secure Professional Staff Through Volunteer Methods. What Is the Middle Way in This Case?

“The solution is very simple. Don’t build large buildings like the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. If you only build structures that can be managed by volunteers, there’s no problem. In the Buddha’s time, ordained practitioners had no one to work for them to resolve their basic needs. This was possible because they slept under trees, wore discarded clothing, and received food as alms. But now, because we want to cook our own food, we need someone to cook; because we want to wear proper clothing, we need someone to manage the clothes; and because we live in large buildings, we need people to manage them.

Particularly when constructing buildings, many professional staff are needed. Hiring professional staff for construction is temporary employment, whereas hiring staff to manage the building afterward is permanent employment. The two have different characteristics. Permanent employment is similar to the old days when nobles employed servants. Only the form has changed—you’re still paying people to work for you. Therefore, practitioners should not hire staff for their daily living. Practitioners should minimize worldly affairs and, even when engaging in them, avoid tasks that cannot be managed independently. However, considering efficiency in the flow of time, we built a large building and fell into this dilemma. Until the building was constructed, Jungto Society had no issues. As we started building, questions about employment arose, and there were many debates during construction. Eventually, we agreed to manage the building with volunteers as much as possible, which is what we’re doing now.

There are many areas within Jungto Society that require professional expertise. For example, editing and publishing videos or preparing for safety incidents in buildings. If non-professionals manage buildings and safety incidents like fires occur, it would cause massive damage and harm Jungto Society’s image. The solution to this problem is not to build such large buildings in the first place. It means not doing things beyond what practitioners can handle. However, following the Buddha’s teachings to spread the Dharma and help those in need, we found ourselves needing larger buildings. To help children who don’t receive timely education, we need to build and operate schools in various places overseas. Schools need teachers, which creates employment relationships with salaries. However, we try to hire part-time or have graduates volunteer to teach children. We try to avoid employment relationships as much as possible, providing food or minimal living expenses in exchange for work. So staff members often need to take on side jobs after finishing their school duties. Currently, we’re operating in a third way that is neither completely volunteer-based nor employment-based. Many people say that while the volunteer approach might work in Korea, it would be difficult overseas. But if overseas relief work cannot be maintained through volunteering, we can simply stop it, so there’s no need to worry.

Jungto Society can continue to exist without the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. However, if we abandon the principles and convictions that follow Buddha’s teachings, Jungto Society’s unique identity will disappear. It would become just another religious organization in the world. What meaning would that have? In ordinary religious organizations, donations are important because they can hire staff to run the organization with those funds. But in Jungto Society, volunteering is more important than donations. Jungto Society operates because of the people who volunteer. If there are no volunteers, Jungto Society would have to close its doors. Until now, the buildings have been managed by retired volunteers who have building management certifications. If this system becomes impossible in the future, the solution is simple. Without complicating matters, we would simply close the buildings.

In most temples, there are dedicated people who manage the facilities. Devotees don’t have to cook, wash dishes, or clean. But in Jungto Society, you must wash your own dishes and clean the spaces you use. Meal preparation is also done by taking turns according to a schedule. So if you think, “I’ve already made donations, do I also have to volunteer?” as you might at other temples, it will be difficult to stay at Jungto Society for long. If you don’t volunteer, you should realize that you’re listening to Dharma talks at the expense of someone else’s sacrifice.

Usually, starting something is difficult, but continuing what has already begun is easier. Buddhism is different. In the beginning, Buddha transcended existing customs and institutions in a truly revolutionary way. However, as time passed, Buddhism gradually became secularized, and its spirit was not properly inherited. Jungto Society will likely become more secular over time rather than adhering to its principles. As time goes on, there’s a greater possibility of compromising with the world rather than living according to the fundamental teachings of Buddha. Even now, compared to when Jungto Society first started, we’ve already retreated in many aspects. While some changes were inevitable as we grew in size and number, I want to embody the spirit of Buddha’s time in this era as much as possible, at least while I’m alive.

If each of you loses your identity as a practitioner, Jungto Society may also become seduced by money or status and gradually drift in a secular direction. The Buddha was indifferent to power and would not even accept dinner invitations from kings. By doing so, Buddhism could remain independent from any country, political faction, or person in power. The Buddha served as a teacher to those in power, not as their follower. However, today’s religious figures often follow the powerful. Jungto Society, which inherits the Buddha’s teachings, should not follow any specific political party or politician. If they come to ask for opinions, we can discuss the direction they should take. But if we follow power, we have already lost our identity as practitioners.”

Today’s talk was an opportunity to reflect on the Buddha’s revolutionary teachings and how Jungto Society continues this legacy in today’s world. The lecture concluded with plans to compare the lives of Buddha and Jesus in the next session.

After the Dharma talk, participants gathered in groups for mindful sharing. Sunim returned to the Jungto Center to conclude his daily schedule.

Tomorrow will be the 58th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will teach the 6th class of the daytime Jungto Buddhism Course, followed by consecutive meetings with diplomacy experts and social figures visiting the Peace Foundation in the afternoon. In the evening, he will teach the 6th class of the evening Jungto Buddhism Course.”