May 24, 2020. Spring Sutra Course Online Special Retreat, Online Meditation Retreat

Hello. Today is a day when the Sutra Course Special Retreat is being conducted online all day. Before starting the special retreat, Sunim worked on farming early in the morning.

Right after finishing morning practice, Sunim went to the field at the foot of the mountain. He had prepared a flat area in one corner of the field to place a water tank.

After finishing breakfast, Sunim returned to the field carrying a rarely used table. He placed flat stones and positioned the water tank on top of the table. He poured water to help the ground become firm.

Sunim connected electrical wires to see if water from the pond he had dug could be transferred to the water tank using electricity.

“Water is flowing!”

Previously, water was collected in a large rubber container, but now having a water tank in one corner of the field provides reassurance. The water supply issue for the field at the foot of the mountain has been resolved. By moving quickly, Sunim was able to complete the planned work before 9 AM. He changed out of his work clothes and headed to the retreat center with light steps.

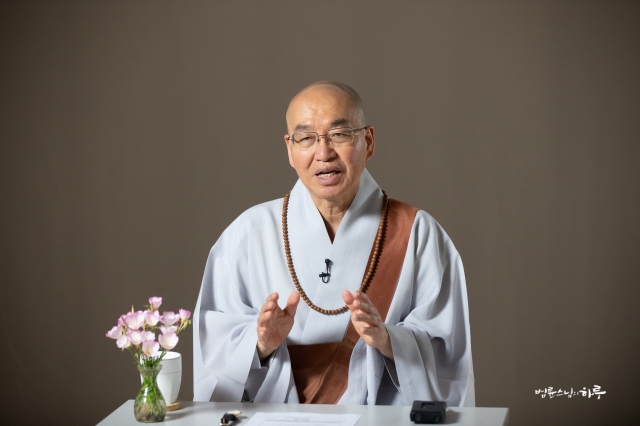

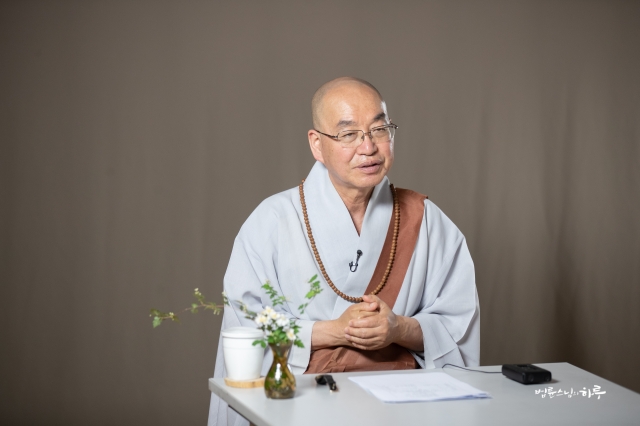

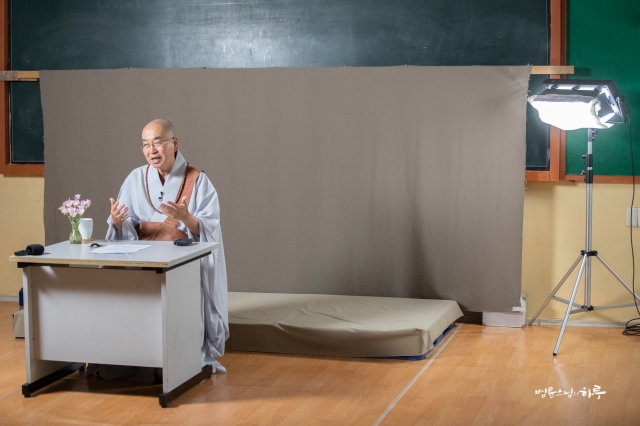

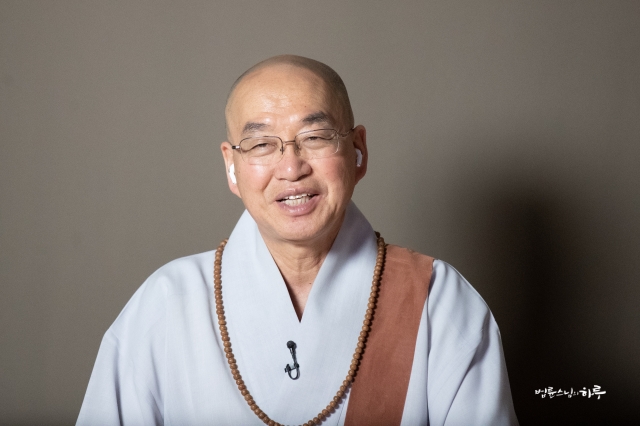

Upon arriving at Dubuk Retreat Center, Sunim put on his kasaya and long robe before sitting in front of the live broadcast camera.

The Sutra Course Special Retreat was conducted via online live broadcast from 9 AM to 5 PM, beginning with the opening Dharma talk.

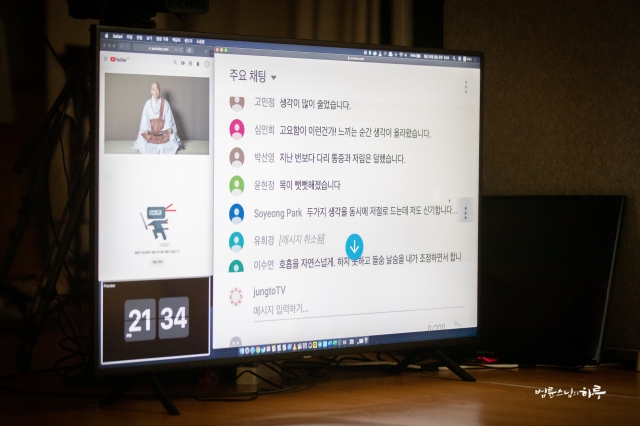

While Sunim delivered the Dharma talk via live broadcast, Sutra Course students gathered at their local Dharma centers to participate in the program. About 700 students from 51 Dharma centers nationwide participated in the online special retreat.

In his opening Dharma talk, Sunim explained in detail the core teachings of the Diamond Sutra that the Sutra Course students are currently studying, and how they relate to the principles of practice, giving, and service that Jungto Society pursues.

“The teaching of the Diamond Sutra is that when facing a problem, rather than avoiding it passively, we can maintain peace of mind by addressing it actively. The core content is found in the third section of the Diamond Sutra. Subhuti asks the Buddha:

‘How can one be free from this suffering?’

In response, the Buddha answers that the way to be free from suffering is to ‘generate the mind to liberate all sentient beings.’ What does this mean?

My Husband Doesn’t Listen to Me and It’s Difficult

Let me give you an example.

‘I’m suffering terribly because my husband doesn’t listen to me.’

In this situation, most religions would approach it by saying, ‘Let’s change your husband so he listens to you better.’ But the teaching of the Diamond Sutra instead tells you to have compassion for your husband and actively listen to him. To someone who is suffering because her husband doesn’t listen to her, the sutra essentially says, ‘You should actively listen to your husband instead.’ When I say this, most people respond, ‘Wait, I’m telling you I’m suffering because of my husband, and you’re telling me to help him?’ They find it difficult to accept.

However, the Diamond Sutra teaches that the moment you generate the mind to actively listen to your husband, all your suffering disappears. In this scenario, the husband benefits from having a better environment with an improved relationship with his wife, while the wife benefits regardless of what the husband does.

However, even then, one cannot completely escape from suffering. While it’s possible to actively cultivate a giving mind because it’s considered good, suffering persists because one still harbors expectations about what one has given. That’s why many people say things like this after giving:

“I helped them so much, and they didn’t even thank me!”

This is secondary suffering. Primary suffering comes from expecting without giving anything. Such people are called ordinary beings. When one moves beyond the stage of an ordinary being to become a wise person, they reason, “It’s not logical to expect without giving first. If I want to receive, I must give first.” They understand the principle that giving is good and act accordingly. However, even then, the purpose of giving is to receive. This is why people who are considered “good” in the world still cannot escape from suffering. It’s like working hard on farming but then regretting it when floods come and destroy the harvest, thinking, “If I had known this would happen, I wouldn’t have farmed at all.”

The Essence of the Diamond Sutra

To prevent this secondary suffering, we are taught to let go of expectations about what we have given. When I understand my husband, my frustration disappears, which means I’ve already received the merit. Not recognizing that I’ve already received this merit, I expect, “Since I’ve helped my husband, he should acknowledge it.” In worldly terms, this is merely the mentality of making an investment to gain profit.

The root of suffering lies not in giving but in expecting. Ordinary beings expect without giving, while wise people give and then expect, but both are rooted in expectation. To completely prevent suffering, one should not harbor expectations. The instruction not to think about having given is not about memory but about letting go of the expectation for merit. This is because that merit has already been received through the elimination of suffering.

“Give, but don’t think about having given.”

This statement is meant to eliminate secondary suffering. Don’t form the notion of having given. In fact, even that giving is not for others but for oneself. Through the act of giving, one becomes joyful, and one’s practice advances.

However, if I think I understood him for his sake, I’m likely to say, “I’ve understood you so much, shouldn’t you understand me at least once?” Then I suffer again when my husband doesn’t understand me. In reality, because my suffering disappeared through understanding my husband, whether he understands me or not is irrelevant. In this sense, the Buddha also said, “Save sentient beings, but don’t think about having saved them.”

This is explained in more detail as “giving without abiding in form” (無住相布施). This is theoretically explained again later as “All forms are illusory. If you see all forms as no-form, you see the Tathagata.” The text continues to explain that the merit of one who practices in this way is immeasurable. It’s not like lending money and receiving interest; it’s immeasurable because it leads to the path of liberation.

I’m explaining the beginning of the Diamond Sutra again today because most of your questions are related to this.

How to Practice Mahayana Buddhism

Based on this principle, at Jungto Society, we first teach Hinayana practice of being aware of one’s mind to become free from external conditions. However, more importantly, we emphasize Mahayana practice. To practice Mahayana Buddhism, first, one must generate bodhicitta. In Mahayana Buddhism, those who have generated bodhicitta are called bodhisattvas. Rather than telling people to shave their heads and become monks or to abstain from certain foods, we teach them to cultivate a great mind. That is, to generate the aspiration to become a Buddha. And to generate the aspiration to share this wonderful Dharma with others.

“I wish there would be no more war in this land.”

“I wish there would be no hungry people in this world.”

“I wish not only humans but all life forms on Earth would be well preserved.”

Generating such aspirations is the path to becoming a Buddha. The more you cultivate such a mind, the greater your mind becomes, the more fulfilling your life becomes, and the less suffering you experience.

First, on a passive level, you must practice managing your own mind well. Second, you must cultivate a giving heart rather than seeking to receive from others. You should practice giving and service to be someone who contributes, even in small ways, to your neighbors and the world. To practice letting go of expectations, perform service without seeking praise or compensation. Thus, giving and service are also forms of practice.

Service Is Practice

In Theravada Buddhism, practice consists of waking up in the morning, bowing, listening to Dharma talks, and meditating. However, in Mahayana Buddhism, giving and service are all considered practice. In Mahayana, practice, giving, and service together are called practice. That’s why Jungto Society places great emphasis on service. People are generally accustomed to giving. However, when performing service, the desire for compensation often arises. Whether seeking monetary compensation or praise, after serving others, we tend to expect something in return. This is why the Diamond Sutra teaches us to vow to save all sentient beings but to let go of the thought that we have saved anyone. To practice this, we need to engage in service frequently.

Service is not something you reluctantly do just to hear Dharma talks. Service itself is practice. While sitting meditation is about being aware of your breath, prostrations are about being aware of your shortcomings. When transplanting rice seedlings, you become aware of the optimal conditions for the seedlings to thrive. Even when picking a sprout, you remain fully aware of the conditions that allow the plant to flourish. While working, you notice when you’re caught up in reluctance, trying to cut corners, and you let go of those tendencies.

This is Mahayana practice. It means making the liberation of all beings your practice. Environmental activism becomes practice, poverty eradication becomes practice, campaigning becomes practice, farming becomes practice, and cleaning becomes practice. You become aware of the workings of your mind during these activities and recognize that suffering arises from expectations. This way, you become happy yourself and useful to the world. You become someone about whom others think, “Being with this person is beneficial for all of us.”

To achieve this, you need to practice giving without expecting anything in return through actual service. First, practice cultivating the mind that helps others, then experience whether it’s possible to let go of expectations after helping others.

So in Jungto Society, you must practice all three: spiritual practice, giving, and service. If any of you say, ‘I will only listen to Dharma talks,’ ‘I will only meditate,’ or ‘I will only do prostrations,’ then in Jungto Society, that’s a ‘No.’ Since Jungto Society is a community of Mahayana practitioners, you must also engage in giving and service. Conversely, if someone says, ‘I will only do giving and service,’ that’s also a ‘No’ in Jungto Society. Since Jungto Society is a community of practitioners, you must also practice transforming your karma. In other words, while you train to benefit others, you must also study to overcome yourself.”

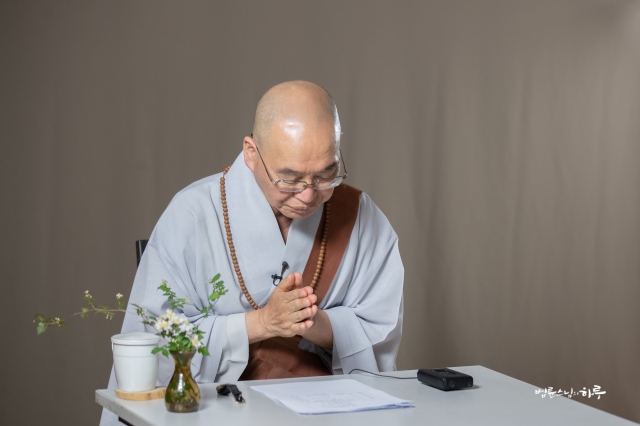

After concluding his opening Dharma talk, Sunim provided guidance about the next program, mindful sharing.

“Now we will have time for mindful sharing. When sharing, talk about your own experiences. Stop speaking vaguely about what’s in books, and instead share your personal experiences about whether you’ve been able to apply what you’ve learned from the Diamond Sutra in your daily life. If you haven’t been able to practice it, explain how it’s not working for you.

In reality, it’s often difficult to put these teachings into practice. However, our goal is to make it work. Practice begins from the reality of not being able to do something and gradually progresses toward the goal of being able to do it. Sometimes succeeding, sometimes failing, but slowly moving forward—that’s what practice is.”

Students watching the live broadcast from local Dharma centers gathered in groups for mindful sharing time. The topic was “The Diamond Sutra, Service, and My Life.” Everyone honestly shared what they had newly realized after listening to the Diamond Sutra lectures and how their lives had changed.

After lunch with the packed meals they had brought, participants from each Dharma center spent time getting to know each other through self-introductions and talent shows.

While the Sutra Course students were bonding at their respective Dharma centers, Sunim received news that Venerable Wonman, whom he had visited recently, had passed away. He immediately went to the funeral home.

“You’ve worked hard. Farewell.”

After paying respects to Venerable Wonman, Sunim helped carry the coffin.

Fortunately, fellow monks arrived and offered to continue the prayers at the crematorium. After thanking them, Sunim left the funeral home. He returned to Dubuk Retreat Center and began the Dharma Q&A session at 1 PM.

Dozens of questions came in from across the country about points that were unclear from the Diamond Sutra classes. Sunim answered fifteen of these questions one by one.

My company is profit-driven and may soon need restructuring due to economic crisis. How can I apply the Buddha’s teaching to “vow to save all sentient beings” in my company?

When the ego disappears, it seems good for understanding others. But without subjectivity, how can one make decisions or pursue initiatives?

I can’t distinguish between forming judgments and developing understanding for others. If someone seems to be lying, should I avoid forming judgments and just let it go? I’m confused about whether I should avoid confrontation as I did before studying.

Is it possible to practice giving without expecting anything in return when official duties require achieving results?

I’m curious about the difference between earnestness and attachment.

While studying the Diamond Sutra, I learned that liberation and saving sentient beings are not separate. How did the Buddha save sentient beings in his time, and how can we save sentient beings in today’s society?

Are people who donate or volunteer privately also saving sentient beings, even if they’re not practitioners?

I’m confused about what it means to not form judgments.

Does “being mindful in daily life” mean focusing solely on what you’re doing? Is it wrong to listen to music while walking or watch TV while eating?

While we can’t say someone is wrong just because their words or actions are different, from society’s perspective…

I feel I should point out issues to people who harm others or don’t fit in well, but should I unconditionally understand and accept them? How can I help them develop the right perspective?

I make regular donations to several organizations. However, when I read news about some organizations misusing donations, I feel anxious about my contributions. What attitude should I have toward giving?

Is “the mind to save all sentient beings” about understanding others and thinking from their perspective? I’d like to know specific ways to practice this in daily life.

When I try to be aware of my anger, I get angrier. It’s less aggravating if I just avoid the angry feelings. How should I practice awareness?

While I appreciate practice, I doubt whether the Buddha really taught about his past and future lives when I hear those stories.

I meditate whenever I have time. Sometimes after meditation, my mind feels so refreshed that I can’t sleep. What should I do in such cases?

It’s difficult to clearly recognize my mind. How should I practice?

Since participants had been watching online lectures all day, some found it difficult to maintain concentration. A short break was taken during the Q&A session.

“Did you rest well? Does it feel better after taking a break? When I give lectures in person, I can go for three hours without a break, but watching videos continuously might be tiring, so we took a short break. Now, let’s continue with the answers to your questions.”

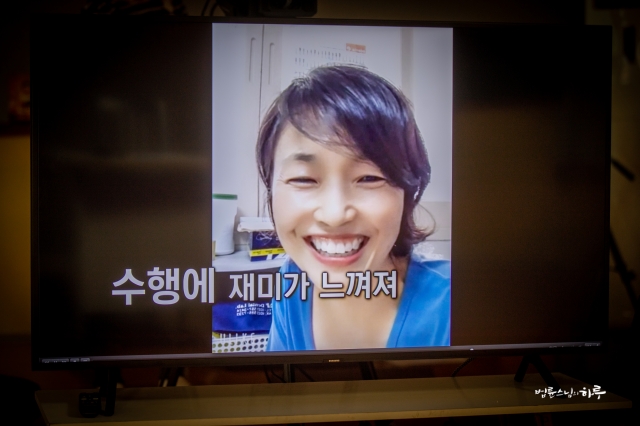

After completing all the answers, Sunim held another sharing session. Following this, participants watched videos of fellow practitioners sharing how their lives had changed since joining the Sutra Course.

“Venerable Pomnyun Sunim seems to teach us how to become happier through sutra study, not just knowledge. I’m always grateful.”

“I’m proud to have developed a practice-oriented perspective. I’m grateful to Venerable Pomnyun Sunim for enabling us to have experiences rather than just acquiring knowledge.”

“While studying the Diamond Sutra, I realized how much I desire things. These days, I’m trying to express my feelings honestly.”

“My irritation, anger, and resentment have decreased significantly. When emotions arise, I become aware of them, and with awareness, they don’t last long.”

“I’ve become much less prone to sudden anger when seeing others’ actions. As these experiences accumulate, practice has become enjoyable. The biggest change is that I’ve developed a desire to practice.”

After watching the video of various reflections from fellow practitioners, everyone listened to Sunim’s closing Dharma talk. Sunim emphasized living a life that reduces mental residue through practice, giving, and service.

“The Buddha said, ‘Call me Tathagata.’ Tathagata means ‘thus come, thus gone.’ It means there is no coming and no going. In other words, it means leaving no trace. In different terms, this is expressed as ‘non-action’ in the sense of ‘doing nothing.’ Doing nothing means having no residue.

A Life of Reducing Mental Residue

Whether the Buddha ate plain food or delicious food, wore fine clothes or patched robes, stayed in one place or went elsewhere, he was not bound by these conditions. If the food lacked flavor, it simply lacked flavor; if it was tasty, it was simply tasty; if the portion was small, it was simply small; if it was large, it was simply large; if given old clothes, he wore old clothes; if given new clothes, he wore new clothes; if there was a reason to go, he went; if there was a reason to stay, he stayed. He had no mental residue like ‘I want to stay,’ ‘I don’t want to go,’ ‘I want to go,’ or ‘I feel confined here.’ This is why he was called ‘Tathagata.’

But we have much mental residue. We feel frustrated when we want to go but can’t, distressed when told to go when we want to stay, troubled when told not to do what we want to do, and burdened when forced to do what we don’t want to do. While having such residue is our reality, our goal is to move step by step toward having no mental residue.

If ordinary people always carry residue, practitioners can be described as those who gradually clear away residue. We clear it away, accumulate more, clear it again, accumulate more—and through this process, the total amount of residue gradually decreases. The accumulated residue slowly disappears, and less new residue forms, so the total amount decreases over time. For those who don’t practice, the total amount keeps increasing.

We all have residue, but the amount gradually decreases. We still have suffering, but it gradually diminishes. We still get angry and irritated, but the frequency of these feelings arising decreases compared to when we first started. Either the duration of anger once it arises decreases, or somehow the amount gradually reduces.

Therefore, we should always look back at our starting point. This allows us to think, ‘I’ve actually made some progress!’ giving ourselves pride and hope. However, looking at the goal, we still have far to go. We still have much residue. Therefore, we shouldn’t become complacent but should diligently practice. That practice is precisely giving and service.

Practice isn’t separate from giving and service. If practice corresponds to somewhat passive self-defense, giving and service actively expand the self. Practice is primarily about protecting oneself from external attacks, while giving and service actively extend help to the world. This combination of practice, giving, and service is the Mahayana practice method.

From Where You Are Now

In Hinayana practice, which focuses on defending and protecting oneself from external attacks, shaving one’s head and leaving secular life is very helpful. However, for active Mahayana practice, even those who have already shaved their heads should grow their hair again, and those without occupations should take up occupations again. For Mahayana practice, one must return to the world, but you are already in the world, so you can practice right where you are. Keep your hair as it is, wear the clothes you wear, continue at your workplace, maintain your marital relationships, and practice, give, and serve.

This doesn’t mean that those who have already become monastics need to get married and grow their hair again. People in one situation should practice from that position, and people in another situation should practice from theirs. Since Jungto Society practices Mahayana Buddhism, I never tell you to ‘become a monk or nun.’ Follow your own conditions. There’s no longer any need to distinguish between whether one is a monastic or not.

Anyone can follow this path. Women in their own way, men in their own way, those with dark skin in their own way, those with light skin in their own way, those who attend church in their own way, those who go to temples in their own way, Koreans in their own way, Japanese in their own way, those living alone in their own way, those who are married in their own way—everyone can follow this path.”

This was the first time a special training retreat was conducted online, a change brought about by COVID-19. Sunim also appeared somewhat tired from having to give a long Dharma talk while only looking at a camera, rather than being in a lecture hall. Nevertheless, he emphasized that practice means making the best use of given conditions, and concluded his Dharma talk.

“Due to the coronavirus, we still can’t gather in large groups. When the government officially declares the end of the pandemic, let’s all gather at Mungyeong Retreat Center and talk while seeing each other’s faces. Until then, let’s continue talking online. It’s not that one way works and another doesn’t—it’s about adapting to whatever conditions arise. Make the best use of the given conditions and continue your diligent practice.”

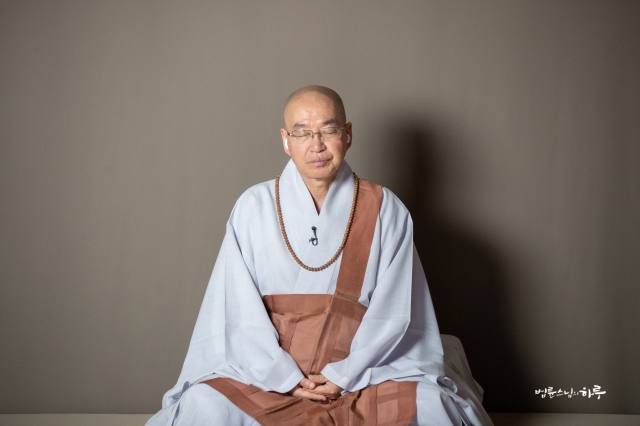

The special training session concluded as everyone recited the Four Great Vows together with the voice coming from the broadcast. After sitting in a chair for so long, Sunim momentarily hesitated when he first stood up.

After the evening Buddhist service, at 7:00 PM, Sunim had a mindful sharing session with the farming team practitioners. Although they had planned to limit each person to three minutes since the online meditation session was scheduled to begin at 8:30 PM, they barely finished the sharing session just as the meditation time approached.

At 8:30 PM, the broadcast camera lights came on again in the training room. The voice of Jason, who volunteers as an English interpreter every Sunday, now sounds familiar.

“Jason, how have you been this week? Thank you for interpreting again today.”

After exchanging warm greetings with Jason, Sunim began the online meditation session.

“Hello, to you all. Today is May 24th, Sunday night. Since we are in late spring, South Korea is already heading into summer temperatures. We already have mosquitoes; they’ve bitten me several times today.”

After briefly discussing the weather, Sunim took time to answer questions that foreigners had submitted the previous week:

• Should I meditate when I’m mentally or physically tired?

• Is it normal for my legs to fall asleep during meditation? Are there alternative meditation postures to prevent this?

Today’s questions were relatively simple. One person asked about losing focus just as their awareness was deepening. Sunim explained that feeling like one’s meditation is going well can actually be the biggest obstacle, and then provided guidance on the correct meditation posture.

“When you lose that awareness, thoughts quickly arise to fill the empty space in your mind. This is a characteristic of mental activity. In an instant, various thoughts—whether about the past or plans for the future—take hold. As thinking becomes more active, energy consumption increases, making your breathing slightly stronger. Then you can detect your breath again. Only then do you realize, ‘Ah! I lost track of my breathing.’

So you become aware of your breathing again, but then your breathing gradually weakens, and if you don’t maintain concentration, you’ll lose track of it at some point. Then other thoughts arise again. At some moment, different thoughts take hold.

If you become tense trying not to lose track of your breathing, your breathing becomes rough again because energy is being consumed. Being aware of such rough breathing isn’t very helpful when practicing mindfulness. Being able to clearly detect breathing so subtle that you can barely tell if you’re breathing or not will be helpful later when practicing mindfulness.

When you continue to be aware of your breath while your body and mind are in a comfortable state, as the questioner mentioned, you can clearly notice your breath while being in a relaxed state. At this point, you might think, “Ah, this is why people meditate!” and feel slightly pleased. A slight attachment to this pleasant feeling arises. However, because you’ve already had the thought, “This is comfortable, this is why we meditate,” your mind becomes scattered.

From that point on, you’re no longer aware of your breath but instead thinking, “How did I just achieve that comfortable state?” as you recall what just happened. You repeatedly want to recreate the pleasant feeling you just experienced. This means you’ve already lost the principle of meditation. You should be aware of the present moment, but you’re thinking about the past, wondering “What was it like then?” This isn’t being aware of your breath in the present; you’re just thinking. This is an even greater obstacle to meditation than losing focus on your breath due to numb legs, drowsiness, or wandering thoughts.

Therefore, when meditating, you shouldn’t think, “My meditation is going well,” “My meditation isn’t working,” “I did well yesterday but not today,” “I’m sleepy,” or “I’m not sleepy.” With your body and mind in a relaxed state, you simply focus your mind on the tip of your nostrils and notice the subtle sensation of breath going in and out. Whether there are thoughts of the past or future, drowsiness, outside noises, or pain in your legs, you leave them as they are and only notice your breath. Even if thoughts like “Yesterday went well” or “Today isn’t going well” arise, leave them be and simply be aware of your breath.

Don’t try too hard to do well, don’t tense up while focusing on the tip of your nose, don’t get frustrated when it’s not working—just be aware of your breath. If you lose focus, start again. Whether you just did well or poorly, these are already past events. Only the inhalation and exhalation in the present moment are real. If you lose focus, become aware again; if you lose focus, become aware again—simply continue doing this.”

After finishing his answer, Sunim immediately began meditation.

Tak! Tak! Tak!

After 30 minutes, the wooden clapper sounded to end the meditation, and Sunim’s voice was heard from the screen again.

“How was it? Please share your experiences. Don’t tell me what you thought, but what you actually felt during meditation.”

Hundreds of comments poured in like a shower. Among them were some written in English.

‘Might have been too tired, I was sleepy’

‘It was relaxing’

‘I was feeling pain in the back of my neck as well’

‘I have no feelings in my legs’

‘I was tired so I would like to rest but after meditation I feel much better’

‘It’s hard to breathe’

‘I might have slept with my neck kicked up in a weird way’

‘I was sleepy so I lost my focus’

‘I went through repetitive cycle of focusing and losing being distracted’

Sunim read each visible comment and then provided a summary.

“When you practice directly, you accumulate many experiences as reflected in your comments. There are favorable feelings like mental clarity and a sense of peace, as well as negative feelings like drowsiness and leg pain. These aren’t mistakes but simply phenomena that occur during meditation. Whether the feelings are favorable or negative, what matters is whether you could focus on the tip of your nose and be aware of your breath amid these conditions.

If you couldn’t concentrate because of these conditions, that’s your reality. Starting from this reality, the goal is to reach a state where ‘you can maintain

awareness of your breath in any situation.’ Just practice consistently. Don’t be discouraged when it doesn’t work, don’t get excited when it works a little; if awareness is present, maintain it as long as possible. When you lose focus, notice that ‘I’ve lost focus!’ and regain your awareness. Just continue with a relaxed mind.

‘What’s the benefit of doing this?’

You want to ask this question, right? If you keep practicing like this, good things will naturally happen. You’ll be able to notice emotions arising and disappearing in daily life much more clearly than now. Like moisture evaporating naturally, your karma will gradually be removed.

At the foundation of our emotions lie accumulated karmic residues. Through meditation, these residues gradually evaporate like moisture, becoming lighter and less intense. People who experience severe emotional fluctuations will find their emotions becoming more stable, while their minds grow lighter and clearer. I don’t need to explain this further—if you practice consistently, you’ll naturally experience these results.”

As the night deepens, the sound of frogs croaking outside the window seems to grow louder. Sunim concluded the meditation session, promising to meet again next week.

Today we’ll end here. Please meditate like this every day, and next Sunday we’ll meet again. And then I conclude with that thought today. Please try to practice this meditation everyday. Next Sunday we’ll do this again together.”

After rising from his seat, Sunim expressed his gratitude to Jason, who provided interpretation, and to the Haengjas who prepared the livestream. With that, he concluded today’s schedule.

Tomorrow, Sunim plans to livestream a lecture for the Jungto Buddhism Course in the morning, followed by a full-day special committee meeting at Dubuk with the Dharma teachers.