Feb 4, 2026. Day 12 of the India Pilgrimage, Shravasti

Hello. Today is the twelfth day of our India pilgrimage. Today, while staying in Shravasti, we visited in succession the stupa of Sudatta, who built Jetavana Monastery; the stupa of Angulimala, who committed evil deeds but was reborn as a practitioner after encountering the Buddha’s teachings; and Jetavana Monastery, where the Buddha is said to have stayed the longest and taught the Diamond Sutra.

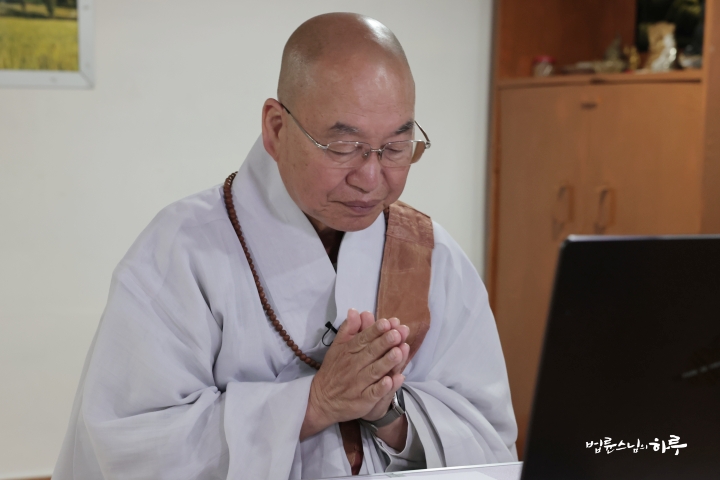

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim began the live broadcast of the Weekly Dharma Assembly at 6:30 AM local time, 10:00 AM Korean time, from the tea room of Cheonchuk Seonwon in Shravasti.

With about 4,000 Jungto Society members connected to the live broadcast, Sunim gave his greeting. He shared about the final leg of the India pilgrimage and spoke about the meaning of practice in following the Buddha’s footsteps.

“Today is Ipchun, marking the beginning of spring. From now on, we’ll gradually start hearing news of spring. In Korea, there has been a severe cold wave for nearly two weeks since Daehan, and I wonder if the weather has warmed up a bit where you are. Since I’m currently in India, I haven’t directly experienced Korea’s cold weather. Today marks the 12th day of our India pilgrimage, and we have only two of the eight sacred sites left to visit: Shravasti and Sankisa.

News on the First Day of Spring, Before the Final Journey to the Eight Sacred Sites

I’m currently sending you this message from Shravasti in Uttar Pradesh, India. After completing our pilgrimage here in Shravasti, tomorrow morning we plan to visit Sankisa, where the Buddha is said to have descended after ascending to Trayastrimsa Heaven to teach the Dharma to his mother. We’ll hold a closing ceremony at the site of the Dharma Center that Jungto Society plans to build for the Sakya clan, where we’ll return our kasayas and bowls. The following day, we’ll travel to Delhi to pay respects to the Buddha’s relics, and then all pilgrimage members will return to Korea. This India pilgrimage is a 17-day journey—long if you consider it long, short if you consider it short.”

Next, they watched a 15-minute photo slideshow showing the journey from leaving Sujata Academy last Wednesday to arriving here in Shravasti. After the slideshow ended, Sunim continued speaking.

“Pilgrimages to the Buddha’s eight sacred sites are an annual tradition for Jungto Society. For those who haven’t been yet, I hope you’ll take this opportunity for field learning. Even those who have already been often say that while the first visit passes by in a blur due to India’s unfamiliar environment, on the second visit the Dharma talks become clearer and they can feel the atmosphere of the sites more deeply. So I hope you’ll reduce other vacations a bit, save up some money, and join this pilgrimage following the Buddha’s footsteps as practitioners at least once every few years.”

He then had conversations with two people who had submitted questions in advance.

As the number of multicultural students rapidly increases, teaching and student guidance are becoming increasingly difficult, and I feel uncomfortable. What mindset should teachers have when looking at students amid such conflicts?

The issue of repatriating North Korean POWs held in Ukraine involves complex international law, human rights, and inter-Korean relations, making judgment difficult. From what perspective should we view this situation?

After giving his answers, it was already time to conclude the Dharma assembly. Fortunately, the internet connection remained stable, and they were able to complete the Weekly Dharma Assembly without interruption.

While the Dharma assembly was in progress, the pilgrimage group had already departed for Sudatta’s stupa at 7:30 AM. As soon as the assembly ended, Sunim also got in a car and headed to Sudatta’s stupa.

At 8:15 AM, Sunim arrived at Sudatta’s stupa before the pilgrimage group. Sudatta’s stupa, with bricks stacked layer upon layer centered on a massive rectangular base on a wide plain, was clearly large in scale even at first glance. In the early morning with thick fog settled in, the ground was wet and the air was cool.

Sunim checked the circumambulation route and inspected whether there was enough space for the five hundred pilgrims to sit all at once.

Shortly after, the pilgrimage group arrived. Sunim circumambulated the stupa with the group and then took a seat in front of the stupa.

Sunim told the story of how Angulimala, who had been a notorious murderer in Savatthi, became the Buddha’s disciple and lived a completely new life.

“We have arrived here at Savatthi in Shravasti. The place where you entered corresponds to the western gate. In the center of the city, two large stupas face each other, and these two stupas have symbolic meaning. Where we are sitting is the stupa commemorating Sudatta. The stupa on the left commemorates Angulimala. Angulimala, who was called the greatest villain in all of Indian history, was completely transformed after encountering the Buddha’s Dharma. He attained arhatship. This is the stupa honoring him.

One person was originally good and became even better after encountering the Buddha-dharma, while the other was evil but became good after meeting the Buddha. Though they were complete opposites in worldly terms, after encountering the Buddha-dharma, both became notable figures in Buddhist history.

Angulimala is a nickname. Anguli means finger, and mala means rosary. He was a man who killed people, cut off their fingers, made them into a rosary, and wore it around his neck. His nickname was Angulimala, meaning finger rosary. His Dharma name later became Ahimsa Bhikkhu, meaning non-violence. You could say he’s someone whose nickname and Dharma name became complete opposites.

From Villain to Saint: The Story of Angulimala

Angulimala was born here in Shravasti to a wealthy family. To ensure their son received a good education, his parents sent him to study in northern India, in what is now northern Pakistan. In the Buddha’s time, this region was known as Taxila. It was a center of advanced civilization, and they sent their young son there to study under a great teacher.

Education at that time seems to have been similar to Korea’s traditional seodang schools. Local children would come to the teacher’s house to study, while students from afar would live at the teacher’s residence. After the teacher’s first wife passed away, he married a young woman. The young wife cooked for and cared for the many students, running what was essentially a school. Angulimala was an exceptionally bright student from abroad. Because of this, he became the object of jealousy among the local children. As an outsider who excelled in his studies and monopolized both the teacher’s and the teacher’s wife’s affection, resentment grew against him.

As time passed and the children grew to the age of today’s high school students, entering adolescence, Angulimala began to develop into a handsome young man. One day, when the elderly teacher was away on business, the young wife confessed her feelings to Angulimala and sought to be intimate with him. Angulimala was shocked and rejected her advances. From the wife’s perspective, she had cared for him with utmost devotion, and when he rejected her love, she felt deeply hurt and betrayed. Her love turned to hatred. She feared that if her husband returned and the boy revealed what had happened, her husband would kill her—as was the custom at that time. So when her husband returned from his trip, she made a false report first. She tore her clothes to expose her chest and was crying. When her husband asked, ‘What happened?’ she said, ‘How could this happen? That boy I cared for with such love turned into a beast when you were gone and tried to assault me.’ The teacher was deeply shocked and began to hate Angulimala.

The stories vary slightly depending on the scripture. Here’s another version: In India, people eat with their hands, and there’s a culture of feeding others by hand as well. This is fine when children are young. However, as the boy grew into adolescence and became more masculine, the wife continued this practice out of habit. Other students watching this felt intense jealousy, seeing him monopolize the lady’s affection. They repeatedly reported to the teacher that something was going on between his wife and Angulimala. Still, the teacher trusted both his wife and Angulimala and didn’t pay attention to the gossip. But one day, when he returned home from an outing and saw his wife feeding Angulimala by hand, he suddenly perceived the rumors as truth. This is how he began to view Angulimala with suspicion, according to this version.

A slightly different story goes like this: A mouse entered the room, and while the wife and Angulimala were trying to catch it, their hair became disheveled and their clothes torn, leaving the wife’s chest exposed. At that moment, the husband suddenly walked in. The two hurriedly tried to fix their clothes, but seeing this, the husband misunderstood the situation.

Either way, the key point is that there was a misunderstanding. Eventually, the teacher said to Angulimala, ‘I have nothing more to teach you. So go home.’ Angulimala insisted that he respected his teacher and wanted to learn more, but the teacher told him to leave. When Angulimala still refused to go, the teacher said, ‘If I must say, there is one more thing to learn. But it is too difficult to practice. That’s why I cannot teach it.’ Angulimala pleaded two or three times, saying, ‘No matter how difficult it is, I will practice it.’ He made this promise. Then the teacher revealed the practice method.

‘Kill one hundred people and make a necklace from their fingers. When you wear a rosary made from a thousand fingers of one hundred people you have killed, you will immediately ascend to heaven. You will be reborn in the heavenly realm in this very body.’

An ordinary person would have doubts about this, but perhaps because he had promised so many times, Angulimala was instantly captivated and said, ‘Yes, I will do it,’ and immediately put it into action. Angulimala took a sword and began killing people. Without thinking it was an evil act, he killed people solely with the thought of going to heaven. He thought of it only as a practice method for ascending to heaven. As he made a necklace from bloody fingers and wore it around his neck while killing people, the news spread incredibly fast throughout the surrounding area. Since everyone fled, he could no longer kill people in that region. So he gradually moved toward his hometown while continuing to kill. This news reached even Shravasti. People trembled in fear. So every household strung up ropes with bells attached, so that if anyone saw Angulimala appear, they could shake the rope to make a clanging sound. As Angulimala came closer to Shravasti, the fear grew greater. When the bell sound rang, everyone would close their doors and stay inside their homes – it became a state of extreme emergency.

King Pasenadi also had to catch the murderer. So he mobilized his army to capture him. Since sending just a few soldiers would result in them being killed instead, rumors spread that Angulimala possessed terrifying supernatural strength. Angulimala’s mother was heartbroken. She had sent her beloved son away to study, but he had returned as a monster. While it was a problem that her son was killing and harming people, it was also a problem if her son were to be killed. The king was mobilizing his army to kill him. So she pleaded with the Buddha to save her son. After hearing Angulimala’s mother’s plea, the Buddha walked toward where Angulimala was coming from. Then people came running from that direction, saying, ‘Angulimala is coming this way, Buddha, please flee quickly!’ as they ran away. The Buddha said, ‘The Tathagata has no fear,’ and slowly walked toward where Angulimala was said to be coming.

Before long, Angulimala appeared with sword and shield. But no matter how much Angulimala chased after him, he couldn’t get close to the Buddha. Angulimala shouted, ‘Monk, stop there!’ and finally managed to get close to the Buddha, panting heavily. He angrily said, ‘Why don’t you stop when I tell you to? Didn’t I tell you to halt?’ Then the Buddha spoke.

‘The Tathagata stopped long ago. The one who has not stopped is you.’

To Angulimala, this made no sense. Angulimala had been running and then stopped, while the Buddha continued walking forward, yet he was saying that the one who hadn’t stopped was Angulimala himself. So he asked, ‘What do you mean?’ The Buddha replied, ‘The Tathagata stopped harming people long ago. But you have not stopped that behavior.’ Hearing these words, Angulimala came to his senses as if awakening from a dream. When he regained his clarity, he realized he had committed terrible evil deeds. Angulimala knelt down and asked the Buddha, ‘What should I do about my sins?’ In this way, after hearing the Buddha’s teaching, Angulimala’s eyes of wisdom opened and he requested ordination. The Buddha accepted him as a disciple, saying, ‘Come, bhikkhu!’ He gave him the Dharma name ‘Ahimsa,’ which means non-violence. Then he brought Angulimala to the monastery.

At that time, King Pasenadi, unaware of this fact, was leading an army of a thousand soldiers to capture Angulimala. As he passed by Jetavana, he dismounted his horse to pay his respects to the Buddha, disarmed himself, and greeted the Buddha. When the Buddha asked, “Your Majesty, what brings you here with an army? Has King Bimbisara invaded?” King Pasenadi explained that he was on his way to capture Angulimala. He said that public outcry was so intense that the king himself had to personally lead the arrest. Then the Buddha said to the king:

‘Your Majesty, what if Angulimala has repented his past and become an excellent practitioner?’

‘Buddha, that would never happen.’

‘But what if it did happen?’

‘If such a thing were to happen, I would make offerings to him.’

The Buddha pointed to a bhikkhu beside him and said, “This is Angulimala.” The king’s body began to tremble like an aspen tree. He should have been armed with guards, but now he had disarmed himself and come alone, and beside him was Angulimala, the notorious murderer. Then the Buddha said:

‘Your Majesty, do not be afraid. He has already ceased all evil deeds and has now become Ahimsa Bhikkhu.’

When King Pasenadi looked carefully, he saw that Angulimala had indeed become an excellent practitioner. King Pasenadi then bowed to the Buddha and said:

‘The Tathagata is truly great. I could not capture him even with an army of a thousand soldiers, and even if I had captured him, I could only have killed him. But the Tathagata, without any weapons, not only captured him but transformed him into a sage. To what can I compare this inconceivable power of the Tathagata?’

Then the king asked Angulimala:

‘What offerings may I make to you?’

‘I need nothing.’

‘Then whenever you need anything, please let me know. I will make offerings to you.’

After saying this, the king departed. This news quickly spread as rumors that “Angulimala has become a monk.” However, when the monks went out for alms in the morning, everyone rang bells and locked their doors. They didn’t know which monk was Angulimala. None of the monks could obtain any alms. So the monks came to complain to the Buddha. When five hundred courtesans had become nuns, public opinion had been very negative, saying that five hundred prostitutes had entered the Sangha. But the Buddha was not swayed by this. The Buddha said:

‘Just practice silently. After one week, the negative public opinion will disappear.’

When Angulimala went out for alms in the morning, at one house a woman was giving birth. When someone said ‘Angulimala has come,’ the woman in labor fainted. The baby was stuck halfway and wouldn’t come out. It was chaos. So Angulimala returned to the monastery and told the Buddha what had happened. Then the Buddha said:

‘Go back to that house and say this: Since I was born into this world, I have never taken a life.’

‘Buddha, I have killed countless people.’

‘Since you became a monk, you have harmed no one.’

The Buddha didn’t consider what happened before his ordination. So he went back to that house and said, ‘I have never taken a life.’ Then the woman regained consciousness and safely delivered her baby.

As this news spread, people began to recognize that Angulimala no longer committed evil deeds. However, the ignorant masses still harbored resentment for his past evil deeds. When they heard he was no longer a fearsome person, they thought, ‘Let’s beat this guy to death.’ The next day when Angulimala went out for alms, crowds of people gathered and threw stones at him and beat him with clubs, massacring him in the street. As he lay there covered in blood, the situation was reported to the Buddha, who rushed to the scene. But he was already on the verge of death. When the Buddha asked, ‘Angulimala, how are you?’ he replied, ‘I have no regrets. I am at peace.’ Then he closed his eyes.

This is how the story honoring Angulimala has been passed down through the ages. While it’s difficult to reform even one good person, when one evil person is reformed, it has an even greater social impact. That’s why such a large stupa was built for Angulimala.”

After the explanation ended, the group recited sutras and meditated briefly.

When the meditation ended, Sunim explained the next schedule.

“From now, we will practice alms round and return to our original place at Jetavana Monastery. Right across from here is the Angulimala Stupa. We will only circumambulate the Angulimala Stupa and then proceed directly to Jetavana Monastery. Please arrange your kasaya properly, hold your alms bowl, and walk the path.”

At 9:10 AM, the pilgrimage group left Sudatta’s Stupa behind and headed toward Angulimala Stupa while chanting.

The Angulimala Stupa was also large in scale, but the iron fence surrounding it gave a different impression from Sudatta’s Stupa site.

After circumambulating the Angulimala Stupa once, they walked toward Jetavana Monastery.

“Shakyamuni Buddha, Shakyamuni Buddha…”

With the sound of chanting, their footsteps gradually became tranquil.

On the way to Jetavana Monastery, they received alms prepared by the Great Master of Cheonchuk Monastery into their individual bowls. Just as the Buddha and his disciples practiced alms round 2,600 years ago, today’s pilgrimage group also received offerings with the heart of practitioners.

After placing food in their bowls, the pilgrimage group focused solely on chanting as they took each step toward Jetavana Monastery.

They arrived at Jetavana Monastery at 10:00 AM. The waves of yellow flowers spread throughout the grounds caught everyone’s attention.

After circumambulating the Jetavana Monastery grounds, everyone gathered in one place. They placed the alms bowls in the center and offered prostrations and offerings to the Buddha.

Sunim then shared the story of how Jetavana Monastery was founded.

“This place where we have arrived is Jetavana Monastery, also called ‘Jeta’s Grove, Anathapindika’s Park,’ and in Pali, it is called ‘Jetavana.’ The founder of this monastery was the merchant Sudatta. His nickname was ‘Anathapindika,’ which means ‘one who helps the lonely.’ In today’s terms, he would be called a philanthropist. This ‘one who helps the lonely’ was translated into Chinese as ‘Giver to the Lonely’ (給孤獨). Sudatta was not the richest person in Shravasti, but he was among the top ten wealthy merchants. Despite being a businessman, he took the lead in helping those in need, which is why he was called by the nickname ‘Anathapindika.’

The Story of Jetavana Monastery: The Grove Purchased by Covering It with Gold Coins

This merchant Sudatta had a friend named Kalanda, who lived in Rajagriha, the capital of the Magadha kingdom. The pond in Bamboo Grove Monastery is called ‘Kalanda’s Pond’ because this Kalandaka dug that pond. Through this friend’s introduction, Sudatta met the Buddha and invited him to Shravasti. The Buddha responded to Sudatta’s invitation with silence. This meant he did not refuse. According to the sutras, when the Buddha accepted, he always responded with silence, and when he refused, he clearly expressed his refusal.

When the Buddha accepted his invitation, Sudatta canceled all other appointments and hurriedly returned here on horseback. The Buddha had promised to visit in three months. At that time, the only monastery where practitioners could stay was Bamboo Grove Monastery, so Sudatta likely built Jetavana Monastery using Bamboo Grove as a model. He examined the location, scale, and internal environment of Bamboo Grove Monastery and tried to find a place in Shravasti with similar conditions. That is, it had to be outside the city gates rather than inside, not too far from the city, quiet, and surrounded by forest. The place that met all these conditions was right where we are now.

However, while King Bimbisara, who donated Bamboo Grove Monastery, could easily offer it because it was his own land, the situation was different for the forest Sudatta found. The owner of this forest was called ‘Jeta’ in Pali, or ‘Gita’ in Chinese, and he was the younger brother of King Pasenadi. Since the forest belonged to a prince, it was not land that could be easily obtained. Why would a prince want to sell his land? However, Sudatta needed a place to accommodate the Buddha and the Sangha community, so he went to the prince and asked him to sell the forest. When the prince heard this request, he became very displeased. He thought, ‘How dare someone make such a request to a prince just because they have some money!’ So he firmly refused Sudatta’s request. Then Sudatta said:

‘I will pay any amount. Please sell it.’

Here, phrases like ‘anywhere is fine,’ ‘I’ll pay any amount,’ or ‘I’ll do anything’ are like blank checks. According to the customs of that time, when someone heard such words, they had to respond and couldn’t simply refuse. It’s the same principle as when Uruvela Kassapa responded ‘There’s only the snake cave’ when the Buddha said ‘Anywhere is fine.’ Eventually, the prince had no choice but to answer. So the prince, with no intention of selling the land, said:

‘If you really want to buy this land, cover it with gold coins.’

Gold was as valuable then as it is now. Asking someone to cover the desired land with expensive gold was essentially saying he wouldn’t sell the land. However, since Sudatta had already said ‘I’ll pay any amount,’ he couldn’t say ‘Don’t talk nonsense and just name a reasonable price.’ When Sudatta left, the prince thought he had given up and gone home. But not long after, the forest keeper came running breathlessly and said:

‘Master, someone is covering the ground with gold, saying they want to buy this land. Did you really sell the land?’

The surprised prince rushed over and saw Sudatta unloading gold from carts and spreading it on the ground.

‘What is this?’

To the prince’s question, Sudatta replied:

‘You said if I wanted to buy this land, I should cover it with gold, so I’m covering it with gold.’

However, he couldn’t cover much before running out of gold. Seeing this, the prince was secretly pleased and thought:

‘This isn’t enough to buy this land.’

Then Sudatta told his servants where his hidden money and loaned money were kept and ordered them to bring it all and spread it on the ground. Seeing this, the prince was greatly surprised inside:

‘What on earth is this person planning to do with this land that he’s going to such lengths?’

So the prince finally asked:

‘What exactly are you planning to do with this land?’

Sudatta replied:

‘I’m preparing a place for the Buddha and the Sangha community to stay.’

When the prince heard this, he was even more dumbfounded. He could understand if a merchant invested to make money, but he found it utterly incomprehensible that someone would spend a thousand gold coins to buy a forest just to provide a place for practitioners to stay. So the prince asked again.

‘Who is this Buddha you speak of?’

Then Sudatta explained what he knew about the Buddha. After hearing the story, the prince said this.

‘If he is such an extraordinary person, I can understand why you are working so hard to prepare a place for him to stay. I will accept only these gold coins. I will donate the rest of the land.’

This is how Jetavana was established. The forest came to be called Jetavana, meaning ‘Jeta’s Grove.’ When translated into Chinese characters, it means ‘the monastery built by Anathapindika in Prince Jeta’s grove,’ which is ‘Gisugupgodokwon (祇樹給孤獨園),’ shortened to ‘Giwonjeongsa.’ This is the founding story of this monastery.

Even if the actions of those whose minds were opened after hearing the Buddha’s Dharma were somewhat exaggerated in the telling, it is clear that their behavior was far from ordinary. Merchants are naturally shrewd about money, but after hearing the Buddha’s Dharma, Sudatta spent money without any consideration for economic efficiency.”

After the explanation ended, they had a meal with the alms food they had collected.

They then chanted sutras and meditated, after which they had some free time at Jetavana. The pilgrimage group spent 30 minutes freely, taking commemorative photos by chapter and enjoying the time.

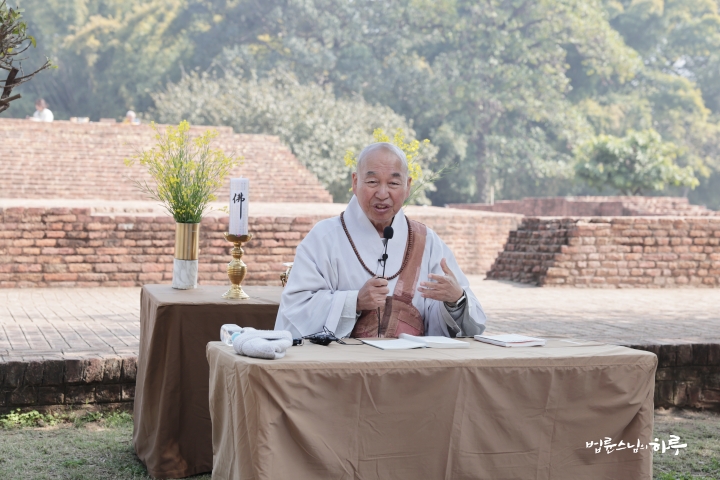

From 2:40 PM, they gathered again to listen to a Dharma talk. Sunim pointed to Jetavana and spoke about the true meaning of a temple.

“We are now gathered at Jetavana in Shravasti, or Giwonjeongsa in Sawiseong, where the Buddha is said to have stayed the longest. Looking around, it’s just a forest without any buildings, and it was like this even in the Buddha’s time. A place called ‘jeongsa (精舍)’ or ‘doryang (道場)’ means a place where practitioners with pure minds stay. From a worldly perspective, a forest where corpses are abandoned is the most impure and filthy place. However, because practitioners with pure minds stayed there, it became a sacred place. The same land can be seen as the most impure place or the most sacred place depending on how you look at it. That’s why we say ‘neither defiled nor pure (不垢不淨)’ – there is nothing inherently sacred or impure. Yet sometimes it becomes sacred and sometimes it becomes impure. The standard is not in the shape of the land or buildings, but in people’s minds.

A Temple Is Where People with Pure Minds Stay

The reason Jetavana could be called the most pure and sacred place in the world was because the Buddha and his disciples kept the precepts purely here, cultivated meditation to calm their minds, and attained wisdom to maintain clarity. It was because practitioners who had fully mastered the threefold training of precepts, meditation, and wisdom stayed here. Even at that time, there were no buildings here, nor were there sculptures like Buddha statues or stupas. To ordinary people, it was just an ordinary forest. Yet in this forest, the Buddha taught the right Dharma and spread it widely. If we say today that ‘we cannot spread the Dharma because we don’t have temple spaces and face difficulties in spreading the Dharma,’ we can say that this deviates from Buddhism’s original teachings. In Korea, when people think of a temple, they imagine a tile-roofed building, but originally a temple refers to a place where practitioners stay, not the form of a building. When I once stayed in a greenhouse on the outskirts of a city, someone asked me this.

‘Sunim, why are you here instead of at a temple?’

From a worldly perspective, that statement might be correct. However, a ‘temple’ refers to a place where practitioners reside, not the shape or form of a building. When I first visited that greenhouse, the owner said to me:

‘Sunim, I’m currently living in this greenhouse on the outskirts of the city because I’m poor, but my dream is to build a temple. Before I die, I really want to build a temple and offer it to you.’

So I replied, ‘I understand,’ and then asked about another greenhouse nearby.

‘Who lives in that greenhouse next door?’

‘My younger sibling used to live there, but they just managed to get a room and moved out.’

‘Then what are your plans for that greenhouse?’

‘I don’t have any specific plans yet.’

So I said:

‘In that case, would it be alright if I came to live here?’

The person replied, ‘If you were to come here, it would be an honor for us.’ So I moved there with several practitioners. In other words, the practitioner training center was relocated there. However, several months later, that person said to me again:

‘We’re living like this now because we’re poor, but I really want to build a temple for you.’

So I said:

‘You’ve already built a temple for me, so what other temple are you talking about building?’

The person was surprised and asked, ‘When did we ever build a temple for you?’ A place where practicing Sangha members reside is a temple. Because they had the aspiration to build a temple, I moved there, and the moment I began living there, it had already become a temple. However, they were still attached to the notion that a temple must be a building with traditional roof tiles.

Actually, I didn’t have this perspective from the beginning. I too once thought that Korean Buddhism was the problem, that temples were the problem, and that monks were the problem. With a single-minded determination to reform Korean Buddhism, I taught university students, educated young monks, and even demanded reforms within the Buddhist order. Then the Gwangju Democratization Movement occurred, followed by what is known as the ‘10.27 Buddhist Persecution.’

The 10.27 Buddhist Persecution was an incident on October 27, 1980, when the Chun Doo-hwan military regime arrested hundreds of monks to divert public attention from the Gwangju Democratization Movement. The regime accused monks of having relationships with women or possessing property, and detained them under the pretext of sending them to Samcheong re-education camps. This caused significant social repercussions. However, legally speaking, none of these accusations constituted actual crimes. Whether a monk was married, had a romantic partner, or owned property was a matter of internal monastic discipline, not something punishable under the Constitution and laws of the Republic of Korea. Nevertheless, the regime treated them as if they were serious criminals. Despite causing such an uproar, not a single person was convicted in court. This incident was a representative case of state power oppressing religion. While it wasn’t an attempt to officially ban Buddhism, it ultimately severely damaged the image of the Buddhist community.

It wasn’t until 30 years later that our government officially apologized for the 10.27 Buddhist Persecution and paid hundreds of millions of dollars in compensation. However, at the time, there was hardly any recognition that this persecution had trampled on Buddhism’s honor. Rather, when I raised the issue, many people defended the persecution, saying things like, ‘Those bad guys deserved it. It’s right for the king to discipline bad monks.’ But the Republic of Korea is a nation governed by law. Individual property and freedom are guaranteed by the Constitution. While it was disappointing that monks couldn’t empathize with or speak out about the people’s suffering during the Gwangju Democratization Movement, I was even more disappointed to see them not even realize the injustice of having their own rights taken away and being oppressed and abused.

‘This group has no hope. Even if they can’t dedicate themselves to others’ rights, how can people who can’t even protect their own rights claim to serve sentient beings!’

I had this thought. At that time, I decided, ‘Rather than stay in this kind of group, I’d rather go to America to study and become an astronomer,’ and left for the United States. There, I met the great master Seoam. When I first met the elderly master, without even knowing who he was, I poured out all my pent-up frustrations.

‘Our Buddhist community is already completely corrupt. How can you, having eaten temple food for so long, not say a single word about this reality?’

The master listened to everything I had to say until the end and then said this:

‘Listen here, if someone sits on a rice paddy ridge and purifies their mind, that person is a monk, that place is a temple, and that is Buddhism.’

The essence of his words was that a practitioner is not someone who has shaved their head, but someone whose mind is pure. Until I heard those words, whenever I thought of a practitioner, I naturally pictured a monk with a shaved head. Of course, I had learned through studying the Diamond Sutra the teaching ‘do not be attached to form,’ but when it came to actually talking about problems in Buddhism, I had always viewed and criticized them solely as issues of institutions and individuals—namely, monks with shaved heads. So while I had been raising my voice about the need to reform Buddhism, this master was telling me, ‘A person with a pure mind is a monk.’

Looking back, I realized that while claiming to reform Buddhism, I had mistaken tile-roofed buildings, institutions, buildings, and forms for Buddhism itself. But when someone with a pure mind sits on a rice paddy ridge, that place becomes a temple, and that person is a practitioner. This perspective is what Buddhism truly is. At that moment, I felt as if I had been struck on the head. I had been attached to forms, thinking that a person with a shaved head was a monk, a tile-roofed building was a temple, and this was Buddhism. When I realized this, my mind became at ease. It made my future work much easier.

Until then, I had poured much energy into monastic education, wondering ‘How can we cultivate excellent monks?’ But when I realized that those with pure minds are monks, I saw monks everywhere. If a temple is where people with pure minds gather, there’s no need to build temples. When people sit together in homes sharing Dharma discussions, they are practitioners and that place becomes a temple.

The reason I share this story is because when the Buddha met practitioners in his time, he didn’t stay in temples or buildings but dwelled in forests. Similarly, Master Seoam taught, ‘Don’t be attached to forms. Anyone with a pure mind is a practitioner, and where such people gather is a temple.’ The Diamond Sutra also states, ‘Don’t be attached to forms. One who sees the Dharma — knowing that all existence is without permanence and without substance — sees the Tathāgata.’ This means the Buddha is not a body or form. That’s why the Buddha said in his final words:

‘Ananda, do not grieve. The Tathagata is not the physical body but the wisdom of enlightenment. Though the body may leave you, the wisdom of enlightenment will always be with you.’

When we hold this perspective, our minds become at ease. We let go of servile thoughts and become confident, gaining composure from our previously breathless lives. We no longer need to decorate or package our appearance.

Why Do We Need ‘Mosaic Buddha’ Now?

Liberating oneself is the starting point of practice. However, today’s world, driven by desire, creates conflicts between people, causes environmental crises, and flows toward solving all problems through force. Historically speaking, we are now in an era like the Spring and Autumn Warring States period. It’s a time when ethics and justice have collapsed, and force alone seems to be the way to solve problems. In such times, we must return to the Buddha’s teachings to establish individual peace, social peace, and social justice together.

If monks who have left home and become ordained have this awareness, it would be much easier for them to work for social change. They can use all 24 hours of the day. But today, becoming an ordained monk means becoming part of the establishment. That’s why it’s difficult to become a central figure for change. So rather than looking for people who can dedicate themselves completely, we need a way for many people to join forces together. With this intention, I proposed to you, ‘Live your own life 90 percent of the time, and let’s use just 10 percent together.’ This means offering one-tenth of our time and resources for service and giving. When ten such people gather, they can generate the same power as one ordained practitioner.

This is ‘Mosaic Buddha.’ In the new era, it’s more important for many to come together to form one character than for one person to achieve complete character. Hydrogen and oxygen each have different properties, but when they combine appropriately, they become water—an entirely new existence. They become a third entity. This is the law of dependent origination. Similarly, though each person may be lacking, when ten people divide roles and combine their strength, their actions can become the actions of a bodhisattva, the actions of Buddha. That’s why we call this ‘Mosaic Buddha’ or ‘Harmonious Buddha.’ We have gathered to walk this path.

While it’s important to pilgrimage to Buddhist holy sites and reflect on the Buddha’s teachings, another meaning of pilgrimage is to experience firsthand that we can live sufficiently with simple food, clothing, and shelter. When we return to Korea after the pilgrimage, we realize anew how conveniently and abundantly we live. Everything looks good. But after just a few days, complaints begin again. So I hope we become aware of Korea’s capabilities and our individual abilities. Just as someone with money might use it to buy drugs or cigarettes and destroy themselves, we must reflect on whether we’re using what we have properly. I want to say let’s not use our abilities for self-destruction but for benefiting ourselves, our neighbors, and the world.”

After giving the Dharma talk up to this point, Sunim received questions about any points of curiosity. Originally, a Dharma assembly was scheduled for this evening at Cheonchukseowon, but it was difficult to hold an outdoor assembly as cold and humidity would set in at night. Therefore, it was decided to hold a Dharma Q&A at Giwonjeongsa today.

Anyone could raise their hand and ask questions about their curiosities.

I have learned about the threefold training of precept, meditation, and wisdom, as well as the Noble Eightfold Path, but regarding the stages of meditation, I have only learned them theoretically without direct experience. Why doesn’t the Buddha teach the assembly in detail about the stages of meditation he practiced and how they lead to insight and wisdom?

I heard that in Kapilavastu, the Kshatriya caste divided life into four periods: the first 15 years for education, the next 15 years for inheriting the family business, the following 15 years working as the head of household, and the last 15 years for wandering. What kind of culture was it to spend the last part of life leaving home to wander and practice?

When we recite the prayer text, we pay homage to various bodhisattvas such as Manjushri Bodhisattva and Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. I’m curious whether they were historically real figures like the Buddha’s ten great disciples, or if they are symbolic beings created to emphasize certain virtues like the Buddha’s great compassion?

After answering all the questions, the Dharma Q&A concluded. Sunim made an announcement.

“As I mentioned yesterday, the staff has done the shopping today. They prepared oranges, bananas, guavas, papayas, tomatoes, carrots, and cabbages. When we leave Giwonjeongsa and return to Cheonchukseowon, we will open the market right before the meal. Each person gets 2 oranges, 2 bananas, 1 guava, 2 tomatoes, and 2 carrots, while papayas and cabbages are 1 per group.”

When the announcement ended, applause and cheers erupted from various places. After concluding the schedule at Giwonjeongsa with the Four Great Vows, the assembly collected the fruits and vegetables prepared by the staff.

Sunim left Giwonjeongsa and moved to Cheonchukseowon. On the way, he visited and made offerings to the practitioners training at Giwonjeongsa.

Arriving at Cheonchukseowon around 4:30 PM, he had dinner. From 6 PM, he had tea and conversation with Venerable Daein, the abbot of Cheonchukseowon.

Jungto practitioners from various countries around the world including Australia, Canada, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Japan, along with the Dharma Teacher group and staff, took turns greeting Venerable Daein and the resident community of Cheonchukseowon.

Venerable Daein looked at each person and greeted them.

After finishing the conversation with the assembly at 7:30 PM, Sunim talked a bit more with Venerable Daein before concluding the day.

Tomorrow, they will wake up at 1:50 AM and travel by bus for about 9 hours. They will depart for Sankasia, the place where the Buddha is said to have descended to earth after completing his teachings in the Heaven of the Thirty-three.