Feb 2, 2026 – Day 10 of the India Pilgrimage, Kapilavastu

Hello. Today is the 10th day of the 35th India Pilgrimage. After watching the sunrise over the Himalayas from the high mountain city of Tansen in Nepal, the pilgrimage visited Kapilavastu, where the Buddha spent his youth, and Kudan, where he reunited with his family after leaving home.

At 2 AM, the pilgrimage group departed for Tansen, a highland city at 2,000 meters above sea level. As the bus began moving, the interior quickly fell silent, and most of the participants drifted back to sleep.

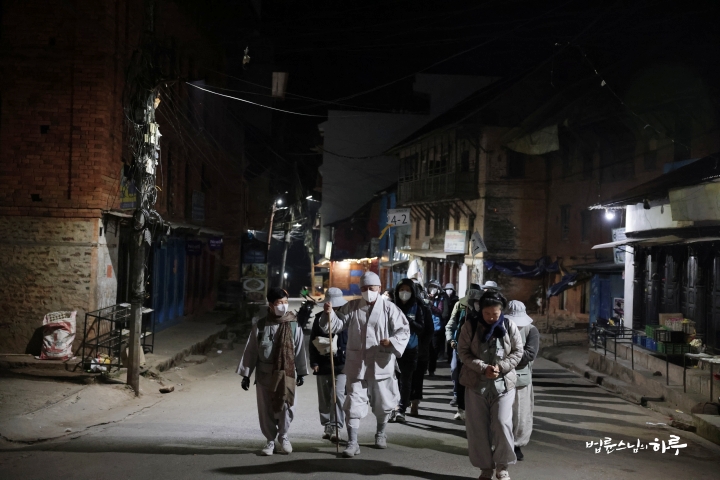

At 5:10 AM, the bus arrived in Tansen. Due to the light fog, they arrived an hour earlier than expected. Though darkness still enveloped the surroundings, Sunim and the pilgrimage group began walking step by step toward the mountain summit.

At the steep stairs, Sunim said:

“It’s difficult for me to lead the way now, so please go ahead.”

Sunim let the following pilgrimage group go first and slowly climbed the stairs.

Around 6 AM, they reached the mountain summit, but the surroundings were still shrouded in darkness. About 30 minutes remained until sunrise.

Sunim found a spot with a good view of the sunrise and settled down with the pilgrimage group, chatting while waiting for the sun to rise.

“They say if you see the sunrise first, you’ll get married this year. So those living in the community and the lay practitioners should stand with their backs to the sun and wait.”

The pilgrimage group burst into laughter at Sunim’s joke.

The sky gradually brightened, but the sun had not yet appeared. Sunim’s voice came through the receiver again:

“It seems like the sun has risen, but we still can’t see it. Actually, by the time, it should have already risen.”

Watching the pilgrimage group busily moving around looking for better spots to see the sun, Sunim said:

“You’re moving around looking for better spots because you can’t see the sun well right now, but in just 5 minutes, you’ll see it whether you want to or not. Everyone will be able to see it no matter where they stand.”

Shortly after, someone shouted:

“The sun is rising!”

Around 7 AM, the red sun slowly rose above the snow-capped mountains. Cheers and exclamations erupted from various spots. Sunim smiled as he watched the sun rising between the Himalayan mountain ranges.

Once the sun had risen sufficiently, Sunim said:

“Now, let’s go eat. There are also spots along the way where you can see the snow mountains well.”

The pilgrimage group followed Sunim into the mountains. He paused at each uphill section to point out spots with good views of the snow mountains. After a while, they arrived at a wide clearing. The sound of people shouting commands could be heard. Upon closer inspection, hundreds of young people were conducting military training.

They moved to another clearing. Once everyone had gathered, they chanted the meal verse and had breakfast with the lunch boxes each had prepared.

After finishing the meal, Sunim informed the pilgrimage group:

“There’s an event in Tansen today, so parking space is limited. They say we need to move our parked buses immediately. Please don’t be late shopping at stores on the way down, and come straight to the parking lot.”

Sunim and the pilgrimage group went straight down the mountain.

At 8:45 AM, after descending the mountain, the pilgrimage group departed for Kapilavastu, where the Buddha grew up. They chose the national highway to go faster, but due to ongoing four-lane expansion construction, the road conditions were poor, causing an additional hour’s delay.

At 12:40 PM, they arrived at Kapilavastu. The pilgrimage group put on their kasayas at the entrance and entered the sacred site while chanting, following Sunim’s guidance.

The pilgrimage group settled next to the ruins of the palace where the Buddha lived as a prince. Sunim spoke about how Siddhartha, before becoming the Buddha, came to accept others’ suffering as his own problem and decided to leave home.

“We have now arrived at Kapilavastu. This place is about 28km west of Lumbini Garden where the Buddha was born, and currently the largest city in this area is Taulihawa.

After completing his studies with his teachers, Prince Siddhartha entered a period of following his father, the king, and learning closely what a king does. The scriptures describe his age at this time as approximately twelve or fifteen years old. It happened to be spring, the time to begin farming, and Prince Siddhartha attended the agricultural ceremony for the first time.

Siddhartha Could Have Become a King. Why Did He Leave the Palace?

The plowing festival was an event where the king drove a plow gilded with gold, ministers drove plows gilded with silver, and those below them drove plows gilded with bronze. Common people held iron plows, and it was a large-scale event where about a thousand people plowed the fields all at once. This was an occasion to display the king’s authority, and King Suddhodana brought Prince Siddhartha to the plowing festival so he could observe and learn from it firsthand.

It is said that this was when Prince Siddhartha saw the world outside the palace for the first time. Upon leaving the palace, he discovered that most of the farmers at that time were slaves, and many of the lower class were dark-skinned Dravidians. They were drenched in sweat with emaciated bodies, wearing tattered clothes, their faces contorted with pain from hard labor. Witnessing this scene, Prince Siddhartha felt deep anguish.

Until then, he had taken for granted the fine clothes, good food, and comfortable life he enjoyed in the palace. Only after directly seeing the lives of farmers and slaves did he finally become aware. He realized for the first time that the abundance he had enjoyed was built upon their suffering.

However, when the farmer struck the ox while plowing, the ox bled and foamed at the mouth as it pulled the plow. As the ox turned over the soil with the plow, small insects hidden in the ground were exposed, and birds followed behind the plow, pecking at these insects. Witnessing this scene, a profound question arose in Prince Siddhartha’s mind.

‘Why must one die for another to live? Why must one suffer discomfort for another to gain comfort? Why must one experience pain for another to be happy? Is there no way for all to be happy together? Is there no way for all to live comfortably together? Is there no way for all to live together?’

This experience can be seen as leading to the Buddha’s later teaching when King Prasenajit of Kosala asked him, ‘How can I become an excellent king?’ The Buddha replied, ‘Do not build your happiness upon the suffering of others.’

Prince Siddhartha, forgetting even that he was attending the plowing festival, sat in the shade of the rose-apple tree grove and entered deep meditation, holding onto the single question: ‘Why must one die for another to live?’ At this time, he was not observing his breath but was completely focused on this one question. This can be seen as similar to bringing up the topic of ‘What is this?’ in Seon Buddhism.

Later, after six years of extreme ascetic practices, the Buddha reflected on this time, as described in the sutras. He questioned whether the depth of concentration achieved through asceticism was actually inferior to what he had experienced as a child meditating under the rose-apple tree. This was because ascetic practices kept him in a constant state of tension, which actually hindered his mind from dwelling in tranquility.

Prince Siddhartha became so deeply absorbed in contemplation that he lost track of time. The sutras describe how, as time passed and the sun’s position changed, causing sunlight to enter the shaded area, the branches of the rose-apple tree moved to continue providing shade over the spot where the prince was sitting.

King Suddhodana had intended to show his son the magnificent spectacle of the plowing festival, but when his son did not appear after some time, he began searching everywhere. Eventually, he found his son sitting quietly under the rose-apple tree, deep in contemplation. The sight was so serene and sacred that the king, without realizing it, bowed before his own son.

The Vow of Renunciation Made in the Face of Aging, Illness, and Death

The most representative event that occurred here in Kapilavastu is the Four Encounters. The Four Encounters can be seen as a story that symbolically shows the conclusion the Buddha reached based on his direct experiences of going out into the world and witnessing reality. The scriptures describe this scene rather dramatically.

One day, the Buddha went out through the eastern gate and encountered an old man. The old man’s hair was white, his skin sagged with layers of wrinkles, his hair had fallen out, phlegm rattled in his throat, discharge crusted his eyes, mucus ran from his nose, and he could barely walk due to pain in his knees. The scriptures describe aging in great detail. In fact, among the elderly beggars on the streets of India, one can see appearances similar to this description, showing how realistically the portrayal of the elderly is depicted. When the Buddha asked his attendant, “What kind of person is that?” the attendant replied, “That is an old person.” He then explained that everyone becomes like this when they age, and no one can escape this fate. Hearing these words, the Buddha realized that he too could not escape this destiny. Therefore, he thought he had no time to spend enjoying worldly pleasures and returned to the palace.

After that, the king instructed that the prince should never be shown elderly people, beggars, or sick people on the streets. However, the scriptures describe that later, a deity called Jakbyeong Cheonja appeared before the Buddha in the forms of an elderly person, a sick person, and a corpse.

When the Buddha went out through the south gate, he encountered a person who was ill but receiving no care whatsoever. This scene is also described in the scriptures as too horrific to fully recount. Seeing this patient, the Buddha clearly recognized that people could suffer to such an extent and that he himself could not escape from such suffering. This can be seen as accepting others’ suffering as his own problem. Once again, he thought he could not waste time pursuing worldly pleasures and returned to the palace.

Some time later, he went out through the west gate and saw a human corpse. The corpse was rotting and festering, crawling with maggots, and being pecked at by birds. When the Buddha asked what it was, the attendant replied that it was a dead body. Through this scene, he clearly realized that everyone dies and that he too could not escape death.

So, was this the first time the Buddha had seen elderly people, sick people, or corpses? No, it was not. He had seen elderly people, patients, and corpses even inside the palace. However, what he saw outside the palace was different. These were people who were old but unprotected and abandoned, sick but left untreated, dead but whose bodies were not even collected and were left on the streets. They were all slaves.

When slaves became too old to work anymore, they were abandoned; when they became sick and treatment costs were too high, they were abandoned; when they died, they were thrown into the charnel grounds without even a funeral. The Buddha directly witnessed the suffering of the poorest and most despised people in the world, realized that he was no different from them, and accepted it as his own problem. This was because if the Buddha had not renounced the world and remained as royalty, he could have become a universal monarch if he had won wars, but if he had lost, he could have been massacred or reduced to slavery. In fact, most of the Shakya clan were massacred after losing in war.

For these reasons, the Buddha made aging, illness, and death the fundamental causes for his renunciation. He did not seek to avoid them, but rather took on the challenge of how to resolve these issues. Because his vow to solve these problems was clear, whenever he felt discouraged during his practice and wanted to quit, he was able to pull himself together. Recalling the suffering of sentient beings that he felt at the time of renunciation, and recognizing that their suffering still remained, his determination not to stop his practice became the driving force of his spiritual journey. Even before the Bodhisattva vows of Mahayana Buddhism were systematically established, the Buddha had already set a great vow to resolve the suffering of sentient beings during his process of renunciation and practice. In this way, the Buddha clearly recognized the contradictions of life that society faced at that time. He keenly felt the limitations of a world where one must die for another to live, where someone must win while another must lose.

Then, going out through the north gate, he encountered an ascetic. This ascetic had an emaciated body and wore tattered clothes, appearing no different from a slave in outward appearance. However, he did not look pitiful at all – his eyes were clear, his posture was dignified, and his demeanor was confident. When the Buddha asked who he was, he replied that he was an ascetic. Through this encounter with the ascetic, the Buddha discovered new hope. He came to think that the path to resolving the problem of suffering might lie in the life of an ascetic. Thus he resolved to renounce worldly life, but at that time his parents would not permit the prince’s renunciation.

The First Mental Turmoil Encountered After Renunciation

Usually, we always pray to ‘become a king.’ We think life is problematic because we cannot become kings. However, the Buddha, despite being able to become a king, chose not to do so. He voluntarily abandoned the throne and left the palace to become a renunciant. This act of leaving the palace to become a renunciant is called ‘Yuseong Chulga (踰城出家).’

When the Buddha left through the eastern gate to become a renunciant, he resolved, ‘I will not return to this palace until I attain the path of enlightenment.’ However, since his father, King Suddhodana, could have sent soldiers to bring the prince back, he rode his horse through three kingdoms to avoid capture. After crossing a great river called the Anoma River, he judged that they could no longer pursue him this far and sent back his horse Kanthaka along with his attendant Channa. Then, holding his hair with his left hand and a knife in his right hand, he cut off his long hair himself. Since he was wearing expensive clothes, he exchanged them with a hunter’s clothes. In this way, he finally took on the appearance of a practitioner.

At the moment when he left home against his parents’ opposition, he must have felt as if he would attain enlightenment immediately. However, enlightenment did not come easily even after three days, five days, or a week had passed. Cold and hunger pressed upon him, insects bit his body, and the cries of wild beasts could be heard. In his mind, thoughts of warm food and comfortable bedding arose, and feelings of regret began to surface little by little. However, expressing that the great Buddha had such regrets would have been difficult for people of that time to accept. Therefore, the scriptures explain the mental turmoil that arises during the practice process by borrowing the format of Mara’s temptations. Whenever such whispers arose, the Buddha recalled the vow he had initially made and continued his diligent practice.

After about a week had passed, unable to endure the hunger, he went down to the village to obtain food. The alms-seeking of that time was completely different from how monks receive offerings today. Obtaining food meant receiving what people had left after eating. When he received that food in the form of a practitioner and put it in his mouth, he immediately felt like vomiting. It smelled bad and was so disgusting that he could not swallow it. At that moment, the Buddha reproached himself.

‘Siddhartha, how earnestly did you desire to become a renunciant? Yet what is this state after merely a week?’

Through this experience, he realized that it was difficult to practice alone with only his own strength. So he decided to seek out a teacher and rose from his seat to journey southward. Thus, the journey toward enlightenment continued with meeting and learning from teachers in Rajgir, which then led to six years of ascetic practice.

While other historical stories can be covered relatively briefly, today’s story must be longer because this period covers the twenty-nine years of the Buddha’s life leading up to his renunciation. His life after that is the story of what happened after he had already attained enlightenment.

Many young people are joining us on this pilgrimage to India’s sacred sites. The concerns of Gautama Siddhartha when he first renounced the world and began his practice were not those of a great sage, but rather the struggles of an ordinary human being. For this reason, they can resonate even more deeply with us living today. That’s why we need to take the story of young Siddhartha even more seriously.”

After finishing the Dharma talk, the group recited sutras. The sutra reading was longer than usual. Before beginning the recitation, Sunim made a comment.

“Today’s sutra recitation will be a bit longer than usual. That’s because we’re covering 29 years of the Buddha’s life.” (laughter)

After completing the sutra recitation and meditation, the pilgrimage group sang “The Song of Renunciation” while facing the eastern gate of Kapilavastu.

After finishing the song, they organized their kasayas and prepared to depart.

“Now we will also exit through that eastern gate, pass by the stupa where the practitioners was met outside the northern gate, and head to Kudan. The path goes through rice fields. Please walk slowly in single file and take in the Indian rural scenery. The mustard flowers will be in full bloom.”

The pilgrimage group followed Sunim out through the eastern gate.

“This is the eastern gate. Young Siddhartha passed through this gate when he renounced the world. Since you have also passed through this gate, today you have renounced the world. Everyone, please face Kapilavastu.”

Everyone stood facing Kapilavastu and chanted before setting off again.

From the village road, children began following the pilgrimage group.

As they entered the path through the fields, scenes of village life unfolded before them. The villagers warmly welcomed the unfamiliar pilgrimage group, and when they seemed lost, people approached to show them the way.

The fields were filled with the green of barley and the yellow of mustard flowers stretching as far as the eye could see. Sunim thanked the villagers who had made way and guided them, offering them gifts.

At 3:30 PM, the pilgrimage group arrived at Kudan. This is the historic site where King Suddhodana personally came out and pitched tents to welcome the Buddha, who was returning to his hometown for the first time in six years after his enlightenment.

The pilgrimage group put on their kasayas at the entrance, circumambulated the stupa once, and then took their seats.

Once everyone was seated, Sunim shared various episodes that took place in Kapilavastu, explaining how the Buddha’s teachings transcended the boundaries of family and class.

“The Buddha first visited Kapilavastu six years after his enlightenment, twelve years after leaving home. At that time, King Suddhodana, Lady Mahapajapati, and Rahula did not wait in Kapilavastu but came out here to receive the Buddha. The highest etiquette of the time was to come out one yojana to receive someone. In Rajagaha, King Bimbisara came out about one yojana, approximately 15 kilometers, from the palace to welcome the Buddha. However, King Suddhodana, perhaps because of their parent-child relationship, came out only about 4 kilometers to this place where he pitched tents to receive the Buddha. This is the very spot where King Suddhodana first met the Buddha after twelve years.”

“That’s why both the Buddha’s stupa and King Suddhodana’s stupa are erected here. There are other stupas as well. According to tradition, that stupa belongs to Mahapajapati, and the one near the entrance is Rahula’s stupa. However, there is no visible stupa for Yasodhara, the Buddha’s wife. This is probably because the fact that an ascetic had a wife didn’t align well with the culture of that time. However, most sacred sites have twin stupas erected. Where Sujata offered food, there are stupas for both the Buddha and Sujata. Where the ascetic was met, there are stupas for both the Buddha and that ascetic. In that sense, since this is where the Buddha met King Suddhodana, it’s appropriate to understand these as the Buddha’s stupa and King Suddhodana’s stupa. The other ruins are traces left from later periods when monks practiced here and built living quarters. The name of this site is Kudan.”

It is said that King Suddhodana had prepared abundant delicious food in the palace and came out to wait, but the Buddha did not enter the palace. News spread that the Buddha was going around the poor houses in the village with his alms bowl, begging for food. From King Suddhodana’s perspective, he could not help but be troubled by the fact that a prince of a nation was begging for alms. While exchanging greetings with the Buddha, King Suddhodana asked, “Why are you begging on the streets instead of entering the palace?” To this, the Buddha replied, “This is the custom of our lineage.” When King Suddhodana retorted, “Since when has the Sakya clan had a custom of begging?” the Buddha said, “It is the custom of renunciant ascetics.” From this passage, we can see that the concepts of caste and clan had already completely disappeared for the Buddha.

At that time, the Buddha gave a teaching to the assembly, and it is said that many attained enlightenment after hearing that teaching. Among the young Sakya people, there was a group consisting of seven princes, who were called the “Seven Princes.” After discussing among themselves, they decided to renounce the world together. This group included Ananda, Anuruddha, and Devadatta. Among them were such outstanding individuals that two of them would later become part of the ten great disciples. Of course, Devadatta would later go down the wrong path, but in the beginning, he was a very brilliant disciple.

Why the Princes Had to Bow to the Barber Immediately After Renunciation

At that time, there was no established renunciation ceremony, so those who wished to become monks had to cut their own hair. Therefore, the Sakya princes went to Upali the barber to have their hair cut. They gave all their ornaments and belongings to Upali and departed. As Upali cut their hair, he thought to himself: These princes possess so much, yet they abandon everything without any attachment and leave. What is there for him to cling to when he has almost nothing? This thought led Upali to decide to become a monk as well.

This was six years after the Buddha’s enlightenment, when the Sangha system had already been established. According to the procedure, those who wished to renunciate would first go to Sariputta for basic education, then renunciate, and afterwards pay respects to the Buddha. However, Upali was unaware of this procedure and went directly to the Buddha. Upon hearing the Buddha’s Dharma talk, his eye of wisdom opened. When he expressed his wish to ordain, the Buddha permitted him by saying, “Come, bhikkhu.”

After that, seven princes renounced the world and came to pay their respects to the Buddha. As the Buddha received their greetings, he said, “Pay your respects to your senior first.” As they greeted each person one by one, they saw that the person standing at the very end was Upali, who had been their servant just a few days ago. It was difficult for them to bow their heads easily in this situation. At that moment, the Buddha said, “Pay homage to Upali.” This pointed out that their minds had not yet fully awakened from the mentality of distinguishing caste and class.

The Buddha then said:

“Within the boundaries of my Dharma, there is no caste. Just as there are four rivers in the world that become one when they flow into the ocean, there are four classes in the world, but within my Dharma, they are one.”

Thus, no class discrimination was permitted within the Sangha. Because of this very point, when people of high status renounced the world, they often faced severe criticism from friends and family. In those days, the Brahmin class would not even make contact with the Sudra class, and one could lose their life merely for stepping on a Brahmin’s shadow. However, the renunciants lived together in the same space. As a result, people around them would mock them for living with those of lower classes.

On the other hand, people of lower classes could free themselves from the consciousness of viewing themselves as inferior by renouncing the world. Objectively speaking, it could be seen as having a kind of social mobility effect. However, for people of higher classes, renunciation was a much more difficult decision.

The Only Inheritance the Buddha Left to His Son

Now let me tell you about Rahula. Since the Buddha renounced the world after Rahula was born, Rahula must have been at least twelve years old. When the Buddha returned to his hometown after attaining enlightenment, many people came out to greet him. However, Princess Yasodhara found it difficult to come forward readily.

From Princess Yasodhara’s perspective, if her husband had passed away instead, the situation might have been simpler. If she raised her son well to become king in the future, she could have enjoyed great honor as the queen mother. However, with her husband living as a practitioner, her own life became constrained instead. While her husband was practicing asceticism, she could not enjoy good food or comfortable bedding alone, and she had to live a life similar to that of a practitioner whether she wanted to or not. Moreover, even when the Buddha returned after attaining enlightenment, while his parents could go out to meet him because they were his parents, she was placed in an ambiguous position where she could not step forward simply because she was his wife. These delicate feelings can be glimpsed in the scriptural records. Princess Yasodhara said to Rahula:

“Rahula, that person is your father. Go pay your respects to him, and while greeting him, ask him for your inheritance.”

These words reveal Princess Yasodhara’s complex emotions. What kind of reaction would one expect if someone asked a renunciant monk for an inheritance? Rahula, following his mother’s instructions, went to the Buddha, paid his respects, and requested his inheritance just as he was told. The Buddha gazed at Rahula for a moment, then said to Sariputta, “Ordain this child.” The greatest inheritance the Buddha gave was not material wealth, but ordination.

King Suddhodana was greatly shocked when he heard this news. It had been difficult enough to accept his son’s renunciation, and even harder to accept when the Buddha’s brothers became monks, but now even his grandson was to be ordained. However, King Suddhodana could not protest directly to his son. Instead, he proposed that it would be advisable to require parental consent for the ordination of minors. The Buddha accepted this proposal as reasonable. Thus, a system was established requiring parental consent for anyone under twenty years of age to be ordained. This became the basis for the novice monk (samanera) and novice nun (samaneri) system. Those over twenty can decide to renounce on their own and do not need parental consent. So was Rahula an exception? No, he was not an exception because his father, the Buddha, had given permission. (Laughter)

Although Rahula became a monk in this way, he faced various problems in the early days because he had entered monastic life at such a young age. It must not have been easy for him to adapt, having suddenly transitioned from living as a prince to the life of a practitioner. He had not even entered monastic life through his own aspiration. Rahula often played pranks, giving false information when members of the Sangha asked where the Buddha was. It is said that some people complained, asking why such a young child had been allowed to become a monk. These stories could not have failed to reach the Buddha.

One day, the Buddha called Rahula and asked him to bring water in a new basin. After Rahula brought the water, the Buddha washed his feet with it and then told him to drink the water. Rahula replied that he could not drink it because it was dirty. Then the Buddha said, “Then use this basin to hold your meal.” Rahula said he could not do that either, because he considered the basin itself to have become dirty from holding the dirty water. At that moment, the Buddha spoke these words:

“Our body is like this basin. Just as this basin was originally clean, our body is also originally pure. However, if we harbor bad thoughts like lying, no one will come near you. Just as one would kick away a dirty basin.”

After hearing this teaching, Rahula had a great awakening and from then on engaged in very deep practice. That is why Rahula is called “foremost in secret practice” among the ten great disciples. This was because he practiced diligently without showing off. In Seon Buddhism, Mahakasyapa is considered the one who inherited the Buddha’s Dharma, while in the esoteric tradition, it is said that Rahula inherited the Dharma after the Buddha.

King Suddhodana Could Only See His Son, Not the Buddha

Whenever someone returned from visiting Jetavana Monastery, King Suddhodana would always first ask what the Buddha ate, what he wore, and where he slept. Even when meeting the Buddha in person, he worried about his daily life, such as food and clothing. He was more concerned about the quality of life—wondering “Why does my son wear such clothes?” and “Why does he associate with such people?”—than about the Buddha’s teachings. In short, King Suddhodana had almost no interest in the Buddha’s teachings themselves. While many of the Sakya clan opened their hearts after hearing the Buddha’s Dharma, it is said that King Suddhodana alone never attained enlightenment. When the disciples found this strange and asked the Buddha about it one day, the Buddha smiled and said:

“King Suddhodana can only see his son; he cannot see the Buddha.”

Attachment can blind people in this way. King Suddhodana only saw what state his son was in, but never opened his heart to the fact that his son had become a great teacher. In contrast, the Buddha’s stepmother, Mahapajapati, opened her eyes of wisdom after hearing the Buddha’s Dharma talk, and later requested ordination, practiced diligently, and attained arhatship, as recorded in the sutras.

Perhaps we are not much different. Parents tend to view their children not as individual persons but always within the framework of “my child.” That’s why they say even when a son turns eighty, his elderly mother still tells him to be careful on the road. While attachment is a precious element in life, we need to reflect on how it can also become an obstacle that clouds the eyes of wisdom.”

After finishing the explanation, sutra recitation was performed followed by a Buddhist service.

After completing the visit, Sunim mentioned the condition of the vehicles the youth were riding in.

“Every year, despite careful preparation of vehicles, some are still in poor condition. I heard that the vehicles the youth are riding in are particularly inadequate. They say it’s more like a cart than a bus. As promised, I will switch vehicles. This will also give me an opportunity to have conversations with the youth, and tonight I will stay with them at their accommodation.”

The youth happily boarded the bus with Sunim. At 8 PM, upon arriving at the accommodation, Sunim immediately held a Dharma Q&A session with the youth.

Various concerns from the youth followed: whether to settle down after living a nomadic life, the distress of being unable to do full-time volunteer work due to illness, and how to handle anger that arises during meditation. Some youth asked about Sunim’s conception dream, while others inquired why Buddhism today doesn’t engage in many social activities, yet Sunim manages to be involved in so many.

After conversing for over an hour, the Dharma Q&A concluded at 9:20 PM. Sunim reviewed manuscripts before retiring for the night.

With this, the pilgrimage schedule in Nepal came to an end. Tomorrow, the group will cross the border back into India to visit Shravasti, where Jetavana monastery is located – the place where the Buddha stayed the longest and taught the Dharma.