October 25, 2025 ━ JTS 32nd Anniversary Commemorative Seminar

Hello. Today is the day of the JTS(Join Together Society) 32nd Anniversary Commemorative Seminar held in the underground auditorium of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center.

After completing morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to The Peace Foundation. After working in the office, he had a meeting with foreign affairs and security experts starting at 10 AM.

In-depth discussions continued on how to resolve North Korea-US relations as a solution for peace on the Korean Peninsula, whether a surprise meeting between President Trump and Chairman Kim Jong-un could be arranged during the APEC summit in Gyeongju, and how the Korean government should respond diplomatically afterward. In particular, they agreed to visit Washington D.C. together next year to arrange direct dialogue with US think tank officials before concluding the meeting.

After lunch, at 1 PM, Sunim attended the JTS 32nd Anniversary Commemorative Seminar. JTS invited many volunteers who had been dispatched to and worked at JTS project sites in India and the Philippines. The volunteers greeted each other warmly in the lounge on the second floor before moving together to the underground auditorium where the seminar was held.

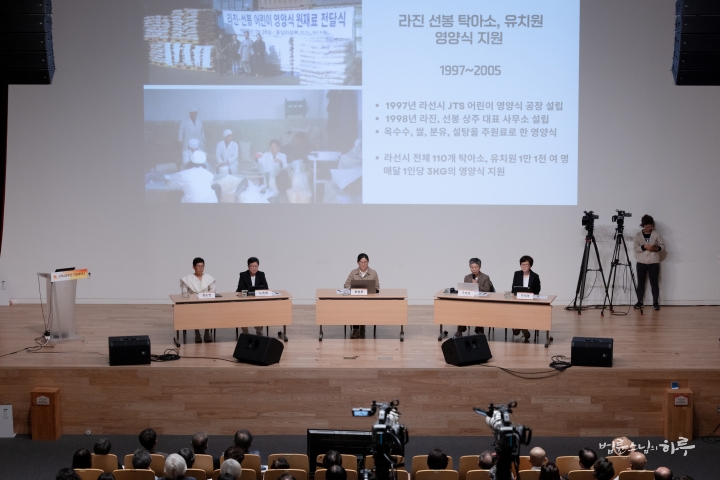

At exactly 1 PM, the MC announced the opening of the seminar and the event began. Celebrating its 32nd anniversary this year, JTS held a seminar under the theme “A New Paradigm for International Development Cooperation: Sustainable Development Through Education.”

This gathering was arranged to look back on JTS’s journey over the past 32 years and explore together the direction international development cooperation projects should take in the future. As the first order of the event, a video capturing JTS’s 32-year history of activities was screened together.

Following this, Kim Ki-jin, Co-President of JTS Korea, gave welcoming remarks, and then Park Young-sook, JTS Secretary General, introduced the distinguished guests in attendance. Many people attended despite their busy schedules from various organizations including the Korea NGO Council for Overseas Development Cooperation (KCOC), UNHCR, The Promise, Happy Allbeings, Crumb Love Sharing Society, Compassion, World Share, Buddhist Environmental Solidarity, Korea Buddhist Culture Foundation, Inter-Korean Peace Foundation, East-West Cultural Development Exchange Association, and Human Asia.

After introducing the guests, the seminar officially began with loud applause. First, Part 1 was a time to reflect together on the achievements of JTS’s 32-year history. Venerable Pomnyun Sunim, Chairman of JTS, gave the keynote presentation. He presented on JTS’s founding philosophy, spirit, and activities.

“There have been many requests from the media and other organizations to share the various experimental activities that JTS has undertaken. Whenever this happened, I always said, ‘We are still experimenting and don’t know what will happen in the future. Also, we don’t have anything clear enough to publicly share yet.’ However, as Jungto Society marked its 30th anniversary, internal opinions grew stronger that we should share JTS’s relief activities and EcoBuddha’s environmental activities that we have been experimenting with to other civic organizations and society. The idea was that by sharing our experiences with society, other organizations could benchmark useful aspects and conduct activities in better directions. So originally, we planned to publicly share JTS’s 30 years of activities at Jungto Society’s 30th anniversary, but we couldn’t prepare in time and only held a commemorative ceremony. After that, many opinions emerged that regardless of other things, JTS projects must be shared with society, so we organized this commemorative seminar for the 32nd anniversary this year. So you can consider today’s gathering as an opportunity to share JTS’s 30 years of activities with our society.

Doing What We Can Has Created Miracles

I’m a bit old-fashioned, so when the volunteers suggested holding a photo exhibition, I opposed it, saying, “How can we use money raised to help those in need just to put up photos?” When they said they needed to build temporary walls for the photo exhibition, I told them to just use the existing walls. When they wanted to publish a book for our 30th anniversary, I opposed it, asking, “Will publishing a book solve the hunger problem?” As a result, we couldn’t properly hold the 30th anniversary ceremony. But this time, the JTS volunteers didn’t listen to me. They went ahead on their own, and today we have this commemorative seminar and photo exhibition. Seeing them proceed despite my objections, I’m thinking, “Should I step back now?”

Of course, it’s good that JTS activities are being made known to the world through such events, but what concerns me is that the values of frugality and simplicity that JTS has always pursued might inadvertently shift toward being results-oriented. I don’t think it’s appropriate to evaluate JTS’s success by the size of our buildings, how much donation we’ve collected, or how many schools we’ve built. I’m not saying we shouldn’t publicize our work, but I believe we shouldn’t do paid promotions. That’s why I don’t allow paid advertising for JTS activities. When we go to relief sites, even if journalists or other external parties accompany us, we shouldn’t use JTS funds for their travel and accommodation expenses. It’s fine if they come voluntarily to cover our work, but we shouldn’t spend JTS funds on promoting JTS activities. Many people have suggested that we should publicize JTS activities to help more people. They’ve also told me, “You shouldn’t think only you are right, Sunim.” Whenever that happens, I simply respond, “Then you come to the field and spread the word yourself,” and leave it at that.

The reason we started JTS activities is based on the Buddha’s teachings. In the sutra that records the day of the Buddha’s parinirvana, there is a question: ‘If the Buddha is no longer with us, won’t we be unable to accumulate the merit of making offerings to the Buddha anymore?’ I don’t know why they worried about this, but anyway, Ananda asked this question. Then the Buddha said there are things that have the same merit as making offerings to the Buddha. First, giving food to the hungry to satisfy their hunger. Second, giving medicine to the sick to heal them. Third, helping the poor and comforting the lonely. Jesus also said something similar: ‘Whatever you did for one of the least of these, you did for me.’ However, the reality is that modern Buddhists make offerings in front of Buddha statues made of stone or metal while ignoring hungry people on the street. When they have money, they think building large temples or making large Buddha statues is accumulating merit. But that’s not what is written in the sutras.

When I first went to India, a poor woman asked me to buy formula because her baby was hungry, but I couldn’t buy it for her. I started the India JTS project as a way to reflect on this wrong action of mine. Rather than helping others, I experienced hunger myself and learned how precious food is, so I share with others. Those who are hungry should be helped by those who are not hungry, and those who cannot read should be taught by those who are educated. The sick should be cared for by the healthy, children should be cared for by adults, and the elderly should be cared for by the young. I think this is what people should naturally do, regardless of Buddha or Jesus. If we eat a little less, wear a little less, and use a little less, with that money we can feed 10 people in poor countries. That’s why I don’t see the ‘miracle of the five loaves and two fish’ in the Bible as just a miracle. If we save the cost of one meal in South Korea and send it to a poor place, 10 people can eat there. If we save the cost of one expensive meal in South Korea and send it, it becomes food for 100 people there. I think this is truly the miracle of the five loaves and two fish.

That’s why JTS doesn’t think about what we can accomplish with money, but rather approaches our activities with the perspective of doing what we can within our means. When I started the school in India, I had no money at all. But there were hundreds of children begging on the streets instead of going to school. So I gathered the children under a tree and started teaching them. Next, we put up a makeshift shelter to use as a classroom, and then as money became available, we built a brick building. I also told the residents to participate in some way. I asked them to play a role as parents since we were teaching their children. They said they had nothing, but they did have some unused land. So the residents donated the land for the school, and when we built the building, the residents came and helped build it together. On the walls, instead of writing who donated how much money, we wrote who came and worked for how many days. In this way, we only built as much as we could at any given time, and we’ve only worked as much as we could.

Sharing Is Not a Sacrifice but a Way to Cultivate My Life

The reason work feels difficult is not because the work itself is difficult, but because of greed. It’s difficult when you want to build a big building without money, but lack of money doesn’t prevent us from teaching children. We can do it under a tree or in a makeshift shelter. There are many things we can do. But it feels difficult because we keep trying to do things bigger and more, and we want to show off with it. That’s why I always keep in mind while working that ‘this work is not for them.’ When I have 100,000 won, I feel much better letting 10 hungry people eat together than buying something delicious just for myself. What good does eating delicious food alone do except make me gain weight? I’ve been working for the past 30 years with this perspective.

I don’t do these activities expecting praise from anyone or blessings from heaven, but with the perspective that ‘living this way is more meaningful for my life.’ So I never think of it as a sacrifice. I do this work as a way to live better. I just do it with the mindset of ‘Let’s do as much as we can!’

That’s why I don’t ask others for help. Since I’m doing something good for myself, I should just do it – asking others for help would be begging. So I think others should see what I’m doing and say, ‘You’re doing good work. I’d like to participate too.’ Of course, JTS occasionally holds street fundraising campaigns as part of member education, but I aim for a relationship where we set an example first, and people are moved by what they see and make donations. Then it becomes a blessing for those who donate, and our activities can also become blessed work.

You shouldn’t have the mindset that you’re sacrificing yourself for others. My life is the most precious thing to me, so if I sacrifice myself for others, how pitiful would my life become? Sharing is not sacrifice. It’s about taking good care of yourself.

Being helpful to others means that you are useful. Just like a broom – if it’s useful, we keep it well, but if it becomes useless, we throw it away. Being useful to the world means that I am valuable. Volunteering is a way of loving yourself and one of the ways to cherish your own life. That’s why Jungto Society is run entirely by volunteers. This makes it inefficient at times. However, we don’t get greedy and only do as much as we can.

And we operate with the principle that donated money should go to those who need it as much as possible. That’s why 90 percent of our fundraising goes directly to people in need.

The Miracle of Students Teaching Students: JTS’s Educational Approach

When building schools, everyone worried, asking ‘Where will we find teachers?’ I told them, ‘There’s nothing to worry about.’ I gathered the local people and asked, ‘Who here has graduated from elementary school?’ Two young people raised their hands. So I made them teachers and started the school. While walking down the road, I met a college student who was moved to hear that a school had been built and volunteered to help. Several young people from other states also came to volunteer, and the school gradually took shape. More children started coming after hearing the rumor that ‘they give you lunch at that school.’ Because we provided lunch, dozens of students flocked in – 5 students in 6th grade, 7 in 5th grade, and so on. Although we originally only had 1st and 2nd grades, we already had about 6 graduates in our first graduating class. Three boys went on to middle school, but three girls couldn’t. The three girls came to me saying they wanted to go to middle school too and asked me to build a new middle school. At first, I said no. ‘We’re already struggling to properly run the elementary school, how can we think about middle school? I studied for middle school while working part-time jobs, so you should just study at home too!’ I said this and sent them home.

The next year, four more female students graduated, and this time seven of them came to me crying. So I asked them, ‘Can you teach and take care of young children?’ When they said they could, I suggested, ‘How about being kindergarten teachers in the morning and studying middle school curriculum in the afternoon?’ This is how middle school students became kindergarten teachers, high school students taught lower elementary grades, and college students taught upper elementary and middle school students. We operated the school with this system of students teaching students.

Starting this way, our activities expanded as we began helping Afghanistan when their situation became difficult, and North Korea when they needed help. In Mindanao, Philippines, we’ve built over 80 schools in the past 20 years.

The people who actually work in the field are numerous volunteers, but all the credit goes to Venerable Pomnyun Sunim. Sometimes I feel a bit sorry about this, but since my role is to be the public face, I gladly accept it. More than 150 people have volunteered for over a year at Sujata Academy in India to get it to where it is today. Dozens of people have also volunteered in Mindanao, Philippines. Many young people have served for one, two, or three years, almost like military service. This accumulation of effort has made these achievements possible.

First, JTS doesn’t overextend itself. Second, we don’t aim to make residents wealthy, but only help them survive with human dignity. Hungry people need to eat, sick people need treatment, and children need to learn at the appropriate time. Learning at the appropriate time means graduating from elementary school. That’s why we rarely build middle schools. However, as time has passed, we’ve built several middle schools in the Philippines recently, and even some high schools. In Cambodia, we’ve even built university dormitories, though this doesn’t strictly align with JTS’s principles.

JTS is Not an Organization That Simply Helps, but a Community We Build Together

However, as society as a whole changes, JTS’s work is currently transitioning from relief to development. In Bhutan, village development has begun under the name of “sustainable development.” JTS builds houses, does interior repairs, paves roads, installs irrigation channels, puts up fences around fields, and installs water supply systems, but the condition is that people must do all the work themselves. JTS provides all the materials, but people must do the work themselves. When someone says, “Please help us!” the answer is “No.” But when someone says, “I’ll do it myself,” the answer is “OK.” If people do a lot of work themselves, JTS provides that much more materials. If they do less work, JTS provides fewer materials. If they don’t work at all, JTS doesn’t provide any support. As a practitioner, I believe that human life cannot be evaluated materially. Ultimately, people gain a sense of accomplishment only when they do things themselves. Only then do they become the masters of their own lives.

Working from this perspective, I sometimes get criticized by local residents. Some people say, “If you’re going to help, help properly. What are you doing?” This is because hardly any other NGO operates this way. But I say, “Really? If you don’t want to do it, then don’t.” Being a monk gives me an advantage. I can speak to the local residents like this.

‘I’m not an entrepreneur; I’m a monastic practitioner. I’m offering to help because you said you don’t have cement to build your house. Why are you asking a monk to help you build the house you’ll live in after marriage? You should build it yourself. Rather, you should be building a house for the monk.’

Then the volunteers nearby say their hearts race with anxiety. At first, people might misunderstand when Sunim speaks so bluntly, but eventually most come to understand, saying, ‘That’s right. We should do our own work!’

If this were a Bhutanese government project, residents would all ask the government to do it. But since it’s Sunim doing it, people say, ‘Even our siblings don’t help us, yet Sunim is helping us. So we should step up and do the work too.’ This sentiment has spread, and villagers in each community are actively participating in communal work. The Bhutanese government initially shook their heads, saying, ‘Sunim, residents won’t participate if you do it that way.’ But later they were amazed, saying, ‘It really works!’ So my position as a monk has become advantageous for the work. (Laughter)

We tell them to use construction materials available in the village and to use the skills that the village possesses. Then people say, ‘Sunim, when JTS builds houses, they should look clean and neat. If they’re not tidy like this, people will criticize us.’ Then I reply, ‘If we bring in skilled workers to build houses, who will fix them when they break down? If we build with village skills, villagers can fix them when they break. If we build with materials produced in the village, they can be immediately replaced when something breaks!’

If we build with plastic or steel frames, we have to buy new materials every time something breaks. It’s not good from an environmental perspective either. It also hinders the villagers’ ability to be self-sufficient. And fuel costs are high for transporting materials. So we try to leave them as they live, thinking we’re just ‘helping a little bit.’ Even if it seems insufficient, there’s no big problem if we wait a little.

That’s why JTS doesn’t accept money from KOICA (Korea International Cooperation Agency). If we receive KOICA funding, we have to complete the project within a year. But if the residents don’t work, we can’t build houses within a year. Then KOICA will hold us accountable. What should we do when the year-end approaches? We have to bring in workers and hurriedly build houses. Otherwise, we have to return the money. After experiencing this several times, we concluded that this method goes against JTS’s principles. So now we don’t accept external funding and only work with money donated by our supporters. If the villagers don’t work, our stance is ‘It’s okay if it takes three years. We’ll wait until they’re ready to work.’ It’s not that JTS has a lot of money and doesn’t need funding. It’s because accepting external funding makes it that much harder to maintain JTS’s principles.

All JTS volunteers are practitioners. We are practitioners who have come together to provide modest assistance to those in material need. Therefore, we don’t become overly ambitious about helping with everything. We think simply: ‘Since I attended elementary school, let’s help those who couldn’t even attend elementary school!’, ‘Since I have clothes to wear, let’s help those who have no clothes!’, ‘Since I am healthy, let’s help those who are sick!’, ‘Since I have a home, let’s help those who are homeless!’ We approach our activities with this light mindset. However, as we work, we tend to become greedy. This makes us place great importance on efficiency. When things don’t go well, we feel tempted to just bring in technicians and workers to quickly get the job done. Many people have complained to me that we don’t work effectively. But shouldn’t everyone live according to their own nature? As practitioners, we shouldn’t focus solely on efficiency.

As time passes, more effective methods will inevitably be introduced. However, I hope JTS will continue its activities without becoming overly ambitious about expanding operations, using methods that allow everyone to participate, and using even small amounts of money effectively. By doing so, although we may remain small in scale, we can become a meaningful organization in our society. For the rest, I hope you will share many good ideas as you listen to the upcoming presentations.”

Through Sunim’s keynote presentation, participants were able to reflect on the founding philosophy and spirit of JTS.

Following this, there was time to examine the specific project achievements JTS has accomplished in the field. JTS volunteers presented on four topics: India, the Philippines, North Korea, and emergency relief.

First, Jang Do-yeon, Director of JTS India, spoke about the journey of Sujata Academy in India and presented on “Self-reliant Life Through Literacy.”

“In this village where most residents are untouchables, being able to read means reclaiming one’s existence. Now children can write their names, and female students say they want to continue their education. Literacy was not just about teaching letters but a process of restoring human dignity. When students reach middle school, they become teachers for preschoolers, and graduates return to their villages to teach younger students. A circular structure has been created where learners become teachers, and those children become new teachers. Now Indian volunteers, not Korean volunteers, run the schools and manage the hospital, and they also volunteer at emergency relief sites. Children who once received help have now become leaders who help others. A tree planted in abandoned land is now drawing water on its own.”

Next, everyone watched an interview video of Ajay Kumar, who shared his journey from poverty to becoming the vice principal of Sujata Academy.

Classes That Started Under a Tree Changed My Life

“As a child, I began studying under a tree in a small village called ‘Bangalbigha.’ One day, when Venerable Pomnyun Sunim came to observe our classes, we all cheered ‘Oh! Oh!’ with joy. Sunim asked, ‘Who comes to school every day?’ and the teacher called me to stand up. I received applause from everyone, and Sunim gave us chocolates and towels as gifts. When I returned home, my father was so happy that he went to the market the next day and bought me a new shirt and shoes. From then on, I began attending school more diligently. At Sujata Academy, they provided shoes, notebooks, pens, food, and learning materials all for free. When I entered middle school, Sunim talked to us about the meaning of service. He emphasized that we must help others to receive help ourselves. I learned the meaning of service by watching Korean volunteers. My life changed greatly through serving as a teacher at Sujata Academy. My father used to get angry a lot, and I did too, but through a life of service, my anger gradually decreased. My son and daughter are also growing up attending Sujata Academy. If JTS hadn’t existed, there wouldn’t have been so many changes in my life. All the changes in Dungeshwari are thanks to JTS and Venerable Pomnyun Sunim.”

Ajay Kumar’s case clearly demonstrated how education can transform lives.

Next, Noh Ok-jae, Director of JTS Philippines, presented on “Community Development and Peace Realization Through Literacy.” She shared the process of how education created peace in Mindanao, a land of conflict and poverty.

“Building a school in Mindanao meant rebuilding people’s lives. In the villages we entered, no one from the grandfather’s or father’s generation had ever attended school. So the first thing residents said was to please build a school so their children wouldn’t live like them. We had to carry materials along mountain paths that were just trails, roads would be cut off when it rained, and sometimes we had to pass through 11 checkpoints of rebels and government forces. Nevertheless, residents offered their land, cleared roads themselves, and carried wood and cement. People who once pointed guns at each other hung their guns on the wall and built schools together. There were times when rebels personally promised to protect the children’s school. After building schools, people no longer feared each other, went to markets, talked with neighbors of different religions, and held village meetings to solve problems themselves. We thought we were building schools, but in fact, we were establishing peace in those villages for the first time.”

The work of JTS Philippines quietly proved that education is a stronger force than guns.

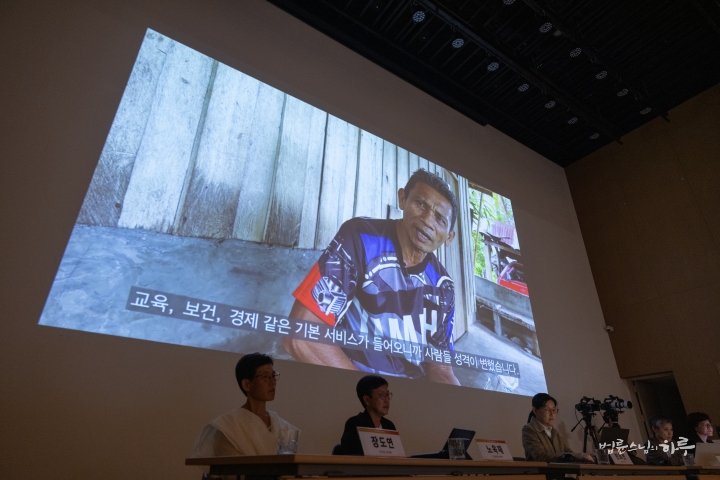

Next, everyone watched interview videos of Anwar Montawal (Kidama Village Leader) and Nomada Samal (Barangay Councilor of Tangkulan, Damulog) who vividly shared stories of local residents’ participation and transformation.

When Schools Were Built, Peace Came to Our Village

“Until 2005, there was no peace in our area. There were always conflicts between Muslims, Lumads, and Christians. Since there were no agreements between tribes, there was no cooperation at all. However, as schools were established, relationships between tribes gradually improved. As children studied together in one school, they naturally became friends. The school became a bridge connecting everyone. As people’s basic needs were met through JTS support, there was less anger toward each other. The biggest change education brought us was peace and order. Even adults avoid fights with the mindset that ‘we are educated people.'” – Anwar Montawal (Kidama Village Leader)

Children Holding Pens Instead of Guns, the Miracle JTS Created

“The government’s presence was virtually non-existent, and we had to evacuate from our homes frequently. My father was a Muslim leader. Since he was constantly pursued by the government, we had no stable place to live. However, because children received education at schools built by JTS, they are no longer ignored and can advance into other fields. In the past, children carried guns, but now they hold pens instead of guns. Without JTS, we wouldn’t have experienced these changes.” – Nomada Samal (Barangay Councilor of Tangkulan, Damulog)

Next, Koo Mi-kyung, who served as an early coordinator for JTS North Korea projects, presented on the achievements of North Korea projects. She reflected on the process of humanitarian aid that began during the North Korean famine in the 1990s, sharing stories of building not just food aid but also ‘trust.’

“In the mid-1990s, millions were estimated to be dying of starvation in North Korea, and children became wandering beggars (known as “flower swallows” in Korean). We started street fundraising campaigns, crying out that we must prevent people from starving to death under any circumstances. When we provided 3kg of nutritional food per month to 11,000 children in nurseries and kindergartens in Rason City, children’s weight increased by 15% and attendance rose by 30% in just six months. Medical facilities were so poor that surgeries were performed without anesthesia, so we directly sent oxygen generators, medicines, and equipment. Through agricultural support, production at demonstration farms increased up to 9 times, and the increased grain went back to nursery children. A structure was created where those who received help could help other vulnerable people. In 2019, we launched a campaign to send 10,000 tons of corn and ended up sending 20,000 tons. Money collected by children at Sujata Academy in India, 1 rupee or 2 rupees at a time, also became meals for children in North Korea. I believe this is the humanitarianism we must protect.”

Though brief, the presentation allowed reflection on the 30-year history of humanitarian aid to North Korea. All attendees gave loud applause for the noble spirit of humanitarian aid to North Korea that continued despite inter-Korean conflicts.

Next, Lee Deok-ah, who served as Director of JTS Afghanistan and is currently a JTS board member, presented on the achievements of emergency relief projects under the theme “Hope Sprouting from the Ashes.”

“During the Pakistan floods, one-third of the country was submerged and 30 million people were affected. We went to the most marginalized areas first, built 203 houses, and installed 2,210 hand pumps so people could drink water again and continue their lives. During the Turkey-Syria earthquake, while most organizations focused on Turkey, we went to northwestern Syria where aid hadn’t reached. By restoring collapsed schools there, 4,000 children began studying again. Schools became not just buildings but ‘symbols of hope’ for children. In Bangladesh’s Rohingya refugee camps, women were exposed to crimes while gathering firewood in the forest. So we distributed 200,000 gas stoves and 6.3 million bars of soap. The anxious refugee camps have now turned green, and people are smiling again. JTS relief is not simply delivering supplies. It’s the beginning of rebuilding collapsed lives and conveying strength and hope to live together even in crisis.”

These were passionate field stories of drawing hope from despair.

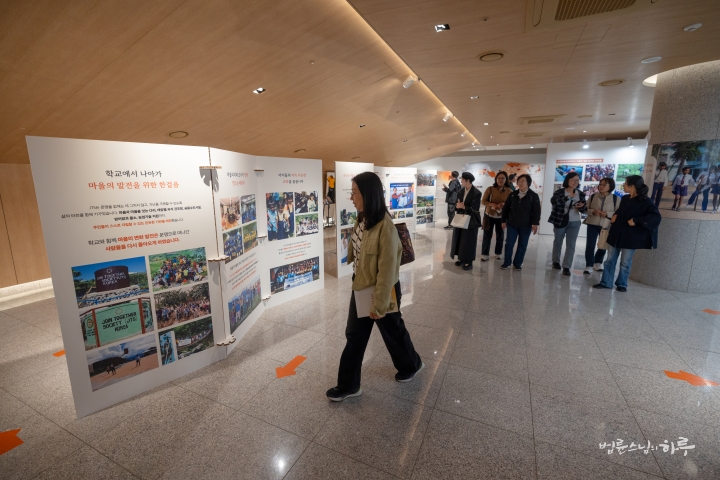

After completing the first part of the program, all presenters and guests came on stage for a commemorative photo. During the break, attendees viewed the JTS photo exhibition in the lobby.

In the lobby, cupcakes and tea lovingly prepared by JTS volunteers were served. While sharing refreshments and viewing photos, attendees reflected on JTS’s domestic and international relief activities. The smiles and eyes captured in each photo conveyed JTS’s spirit of working together.

Sunim had tea and conversation with the attending guests and presenters before moving together to the main auditorium.

Starting Part 2, Lee Su-jin, an early JTS India volunteer who created the Sujata Academy school song, led a warm-up session. The atmosphere became lively again as everyone sang the Sujata Academy school song together and learned four-beat hand movements to the song “Beautiful World.”

In Part 2, four presenters shared their perspectives on the role and direction of education from their respective fields under the theme “Vision and Prospects for International Development Cooperation Education Projects for Civilization Transformation.”

First, Professor Yoo Sung-sang from Seoul National University began his presentation with humble greetings.

“Until I came here today, I had prepared what I would share to some extent. However, after listening to Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s keynote and Part 1, I momentarily felt at a loss about what story I should tell and how to continue. As a scholar who has researched education all my life, I wasn’t confident about how my words could reach those who change the world with sweat and practice with heart. Nevertheless, I thought there must be a reason for me to stand here today. If even one phrase from my words touches your heart, I would consider that gratitude itself.”

Professor Yoo emphasized that education should be understood as a verb rather than a noun, explaining that education is a practice that leads social change beyond knowledge transfer and a public good for community growth.

Noh Ok-jae, Director of JTS Philippines, emphasized that education is a process of recovering human dignity and self-reliance, sharing specific cases from JTS India and JTS Philippines that led community transformation through participatory circular education models.

Lee Seon-kyung, Director at the Korean National Commission for UNESCO, spoke about the importance of education that leaves no one behind, sharing how women’s literacy education and vocational skills training through the Bridge program brought life changes.

Gong Seon-ju, Director of ADI, demonstrated how education can be a force for healing and recovery even in the midst of conflict and disaster, introducing cases where Rohingya refugee women have grown into leaders through education.

The four presenters, through their experiences in different fields, emphasized that education is not merely a process of learning but a fundamental force that restores human dignity and drives community transformation.

A Q&A session followed. Professor Yoo Seong-sang spoke first, emphasizing that JTS’s activities over the past 32 years represent a case of implementing the essence of education through action rather than words. He described the educational transformation as “unnamed educational practice” and suggested that it is now time for JTS to clearly articulate the name and meaning of its work so that its achievements can be more widely known and more people can participate.

Director Lee Seon-kyung compared JTS projects with UNESCO projects and evaluated them. She noted that while UNESCO operates on a commissioned project structure with project cycles of about 10 years, it was impressive that JTS has sustained projects in single regions for over 20 years.

Director Gong Seon-ju shared that after conducting Rohingya refugee women’s education projects for seven years, she realized that while 10 years feels long in international development, year seven is actually when real change begins to emerge. She reflected that her biggest mistake was initially thinking of herself as an expert and trying to provide direction to local residents, learning that true expertise lies with the people who live there.

Director Lee Seon-kyung then asked a question about JTS’s activities.

“In the earlier video, there was mention of people becoming less angry. I’m curious whether JTS has incorporated psychological approaches or religious elements alongside simple learning in the educational process.”

Sunim, who was sitting in the audience, answered this question.

“I believe the reason villagers have become less angry is the result of broadened mutual understanding. Previously, people didn’t know much about those from different ethnic groups, religions, or villages, which led to misunderstandings and consequently to disputes and anger. However, as they built schools together, communicated, and their children attended the same schools, they naturally came to understand each other and conflicts decreased. I see this as change that came through shared experiences rather than the result of any special education or meditation practice.”

Various questions also poured in from the audience. One person mentioned JTS’s achievements in basic education and asked about the conditions and timing needed for this education to develop beyond simple basic levels into quality education.

What Is Needed to Progress from Basic Education to Quality Education?

Sunim, who was sitting in the audience, also answered this question.

“Sujata Academy started with the goal of eradicating illiteracy. However, after 30 years, Indian society has also undergone many changes. While there were almost no government schools in the past, now four or five government schools operate within the area where Sujata Academy is located. Accordingly, Sujata Academy has decided to accept only elementary students from areas without government schools, assigning children from villages with government schools to those government schools. This is to prevent duplicate investment in the same area. Although there was initial resistance from residents, the system is gradually settling in through detailed school assignments by village. However, exceptions are made for children from the untouchable caste who cannot adapt to government schools. This is because if a child cannot attend school and discontinues their education, it goes against the purpose of eradicating illiteracy.

Currently, Sujata Academy has almost achieved its goal of eradicating illiteracy. With preschools operating in each village, most children are already overcoming illiteracy at the preschool level, and many parents have received at least elementary or middle school education. Sending children to school has now become a natural part of the culture, so discussions are ongoing about whether to discontinue the project or transform it in a new direction.

Meanwhile, as the Indian government has strengthened teacher qualification standards, it has become difficult to maintain the school system that was run primarily by volunteers. With high schools and universities also mandating student attendance, college student volunteers can no longer reside at schools. Therefore, the future challenge is deciding whether to convert schools into private schools and reorganize them as specialized institutions. If converted to private schools, the plan under consideration is to hire professional teachers to provide advanced education while enabling children from lower castes to attend through scholarship programs. However, there is internal opposition that such changes don’t align with the founding purpose, so discussions continue.

However, the situation in the Philippines is different from India. There is still high demand for school construction in the Philippines. The educational environment in the Philippines is similar to Korea in the 1960s-70s, still at a stage where schools need to be continuously built. Of course, JTS has a principle of building new schools when villages without schools are more than 4km away from existing schools. In reality, it’s difficult for children to walk more than 6km to school.

Currently, school construction is expanding to indigenous villages in mountainous areas, and recently the demand for schools for students with disabilities has been rapidly increasing. With movements to establish at least one school for students with disabilities in each county, half of the recently built schools are for students with disabilities rather than remote area schools. Accordingly, JTS is now interested in activities that improve educational quality, such as teacher capacity building programs and student experience programs, beyond simply building schools. In particular, programs that provide opportunities for children with disabilities and remote area students to connect with the world through field trips and experiential activities are being offered.

However, the reality in the Philippines is that classroom shortage remains the biggest problem. Local government officials say that due to limited budgets, they must prioritize expanding general classrooms for the majority of students over schools for a small number of students with disabilities. In some areas, school construction is only possible with JTS’s financial support, as government budgets alone would never reach them. According to education office data for Bukidnon Province in Mindanao, while more than 2,000 classrooms are needed, only about 20 can be built annually with the budget. Therefore, in the Philippines, securing basic learning spaces is more urgent than discussing ‘quality of education.’

Finally, in the case of Bangladesh’s Rohingya refugee camps, the biggest problem is that education itself is not permitted. The Bangladesh government prohibits teaching refugee education in Bengali, the local language, and only allows education in the Myanmar language. However, the Rohingya refuse Myanmar language education, and there aren’t enough teachers who can teach in English. Online education was attempted, but even that became impossible when the government banned refugees from using the internet. Among approximately 1 million refugees, 40% are youth, meaning over 400,000 are outside the education system — a serious situation.

Consultations with various international organizations are underway to solve this problem, and recently some educational systems are being piloted through cooperation with UNHCR. However, conditions still make it difficult for substantial education to take place. I think this is the most urgent challenge that needs to be addressed.”

After the presentations and Q&A session, closing remarks were heard from the four presenters.

Director Gong Seon-ju said she came to reconsider the meaning of value created by people, beyond the word ‘efficiency’ commonly emphasized in international development fields.

“When we talk about international development or humanitarian aid projects, we always emphasize efficiency and accountability. But listening to JTS’s project presentation today, I felt there are precious values that cannot be created through efficiency and speed alone. I hope the experiences JTS has accumulated in the field over the past 32 years can be organized not just as simple achievements but as a system of meaning.”

Director Lee Seon-kyung emphasized the importance of cooperation and sharing.

“Through occasions like this where we learn from and share with each other, new ideas and possibilities open up. I gained many insights today and discovered room to further develop my own projects.”

Secretary General Noh Ok-jae then shared his realization that JTS’s activities were ultimately education itself.

“If we were to name JTS’s activities over the past 30 years, it would be education. We didn’t simply build schools – people sought paths of learning to live more happily, and in that process, lives changed and villages transformed. Though we didn’t realize it at first, the essence of what we’ve done was ultimately education. I think it’s now necessary to express JTS’s experience in social language and share it with other development organizations.”

Finally, Professor Yoo Seong-sang defined JTS’s activities as an ‘educational experiment’ and expressed deep respect.

“Seeing JTS grapple with different problems in India, the Philippines, and Bangladesh makes me reconsider the true meaning of education. India is contemplating direction after eradicating illiteracy, the Philippines is questioning why they must handle quantitative expansion, and Bangladesh is pondering how to achieve education under impossible conditions. Education is different from simply providing necessities. Education doesn’t show immediate effects like bread or medicine. It takes a long time to see results. That’s why JTS has finally given the name ‘education’ to its activities after 32 years. Education is a force that transforms not just individuals but communities. Education is the process of learning how to live together, not just for oneself but for all of us.”

Finally, Sunim gave closing remarks to wrap up today’s seminar.

“After listening to your presentations, first, I think we can evaluate that ‘JTS’s work has had many achievements, and the content is moving.’ But when I think about ‘Why does it feel that way?’ and ‘What special work did we do?’, I think it’s actually thanks to choosing our project areas well more than any other factor.

Change Appears Greatest When You Start in the Most Difficult Places

I think the changes were clearly visible because we worked in the most disadvantaged areas. If we had worked in well-off areas, it would be difficult to feel much change comparing before and after the project. But because we went to such poor and dangerous places to help people, although it was hard for us, others feel ‘Wow, it’s changed a lot’ and ‘There have been great achievements.’

Second, you might wonder ‘Why did JTS choose education as the seminar theme among all the various things it has done?’ The reason is that the results in education are clear. For example, we can clearly show results like how the literacy rate in Dungeshwari village in India, where Sujata Academy was established, has dropped from nearly 100% to about 30%. Education is a field where we can clearly demonstrate such achievements. In fact, JTS has invested more in other areas than education. We’ve spent the most money on distributing relief food. But food aid shows little visible results compared to the investment. We can’t produce statistics on how many people survived thanks to relief food. And in the medical field, while hospital buildings are visible results when built, we can’t know how many people were healed by medicine. In contrast, education captures student numbers in statistics, and children going to school daily is visible in villages. That’s why education became the theme for evaluating the past 30 years.

Third, one of the presenters just mentioned trying to withdraw after 7 years of activity but being unable to do so. I understand that feeling. Because if it had been a support project for adults, we could have withdrawn after 5 years of support, but we started supporting preschool students. Those children have now become young adults over thirty years old. Only now can we do village development and create rural communities with these young people. Before, no matter how much we wanted to do village development programs, we couldn’t because there were no people, but now we can do anything with the children who have become young adults. In a word, it’s now manageable.

From Relief to Development, JTS Standing on a New Path

My original plan was to build only elementary schools in Dungeshwari and then withdraw, connecting school building projects along Buddhist holy sites in a line. Later, I dreamed of expanding to cover areas and ultimately eradicating illiteracy in India. But we haven’t been able to leave Dungeshwari and have been stuck here for 30 years. The reason we initially provided higher education to children here was to secure teachers for literacy eradication, not for university admission itself. With these concerns, we’re at a crossroads of whether to end the literacy eradication project and transition to other projects, or continue educational support while expanding to higher education. In other words, JTS is now in a situation where it needs to transition from relief work to development work.

But when JTS first started, we clearly decided to do only relief work. So internally, there are concerns that ‘As practitioners and environmental activists, we should withdraw from things like development rather than relief.’ On the other hand, there are opinions to ‘Set a new goal of sustainable development and transition to development,’ so we’re experimenting with that in Bhutan.

So if possible, you should also try starting relief work in the most disadvantaged areas. When spreading the dharma too, it’s easier to feel the change when converting people with the worst temperaments. Converting good people shows no visible results. So although it may be difficult immediately, it’s good to work in difficult, disadvantaged places if possible. You can get very clear results in terms of effectiveness and evaluation. The places where JTS started its work were exactly such places. Listening to your presentations today, I thought that JTS’s results appear outstanding because we started work in the most difficult and disadvantaged places.”

With the hope that the vision we shared today will become the seed of a new civilization transformation, we concluded the JTS 32nd Anniversary Seminar with a big round of applause.

After the seminar, all the volunteers who had been dispatched to India and the Philippines came up on stage to take a commemorative photo with Sunim.

Each participating volunteer received a book containing the 30-year history of JTS as a gift. Before the official release, seminar attendees were also able to take the book home with a small donation.

Sunim expressed his gratitude to the volunteers who took time from their busy schedules to visit JTS after a long time, then left the underground auditorium.

As the sun set, Sunim departed from Seoul at 6 PM and headed to Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center.

After driving on the highway for 3 hours and 30 minutes, Sunim arrived at Dubuk Jungto Retreat Center at 9:30 PM and concluded the day’s activities.

Tomorrow is the fifth day of the Women’s INEB(International Network of Engaged Buddhists) program. In the morning, there will be a Q&A session on the theme of Jungto Society’s social engagement. In the afternoon, participants will visit Bulguksa Temple, and in the evening, they will have a dialogue session with Sunim.