Sep 11, 2025 – European Lecture Tour (4) Düsseldorf

Hello. Today is the fourth lecture of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s European tour, held in Düsseldorf, Germany.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim had a simple breakfast and departed from Amsterdam at 6 AM, heading for Düsseldorf.

The 230-kilometer journey from Amsterdam to Düsseldorf was made by car. Ms. Choi Soon-jin, a Jungto Society member living in Duisburg, came to Amsterdam to serve as a driver.

After driving for three hours across the A3 and A12 highways that cross southeastern Germany from the Dutch border, Sunim arrived in Düsseldorf at 9 AM.

After arriving at Ms. Choi Soon-jin’s house, which served as accommodation, Sunim greeted her with three bows and they had lunch together.

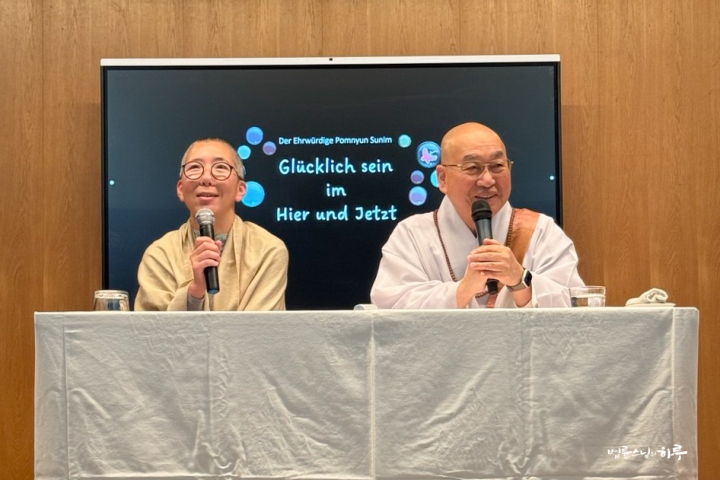

Today in Düsseldorf, two lectures were scheduled: one with German interpretation for local residents and a Dharma Q&A for Korean expatriates. To conduct the German-interpreted lecture first, Sunim left the accommodation at 1:20 PM and headed to the venue.

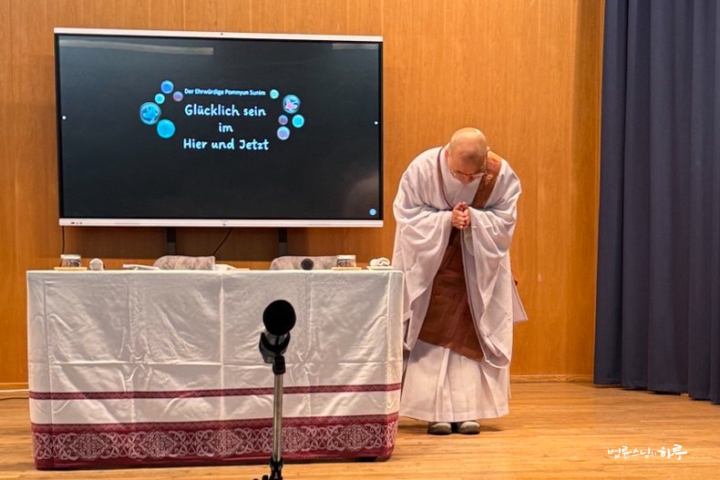

The lecture was held at the Gerhart Hauptmann Haus, located at Bismarckstraße 90 in downtown Düsseldorf. This venue, which preserves and promotes the culture of people who migrated from eastern Germany or left their homes due to conflicts, hosted Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s Dharma Q&A today. When Sunim arrived at the venue, volunteers warmly welcomed him.

About 30 Germans attended after seeing various promotional materials. This was the first German-interpreted lecture in Jungto Society’s history.

At 3 PM, after watching an introductory video about Sunim, the lecture began. First, Sunim gave his opening remarks.

“Nice to meet you all. Since I don’t speak German, I’ve only given lectures to Koreans until now. But today, thanks to an excellent German interpreter, I’m very happy to be able to have a conversation with you.

A Living Dialogue Where Suffering Disappears

A Dharma Talk is a conversation between people. However, we don’t call our everyday conversations or discussions about Buddhism a Dharma Talk. A Dharma Talk refers to a conversation about an individual’s suffering or questions, during which that suffering or doubt disappears. The ultimate goal of a Dharma Talk is for us to reach a state free from suffering. It’s not a conversation for gaining knowledge. As we go through life, everyone develops many questions and sufferings. We talk about these sufferings casually, as if talking to a friend, saying ‘I have this difficulty.’ There are no predetermined answers when we converse. However, through conversation, you might think ‘It’s not a big deal’ or find a clue thinking ‘Ah, I can do it this way.’ I’m not giving you answers; rather, through our conversation together, you find your own path.

Originally, Buddhist scriptures are collections of records of conversations between people suffering and the Buddha, where they confessed their suffering to the Buddha. Studying scriptures today means studying those ancient dialogue records. However, I think it’s more important for us to have such conversations today than to be curious about ancient people’s dialogue records. In Seon Buddhism, past stories, old stories, and others’ stories are called ‘dead phrases’ (死句), while my story and stories of this moment are called ‘living phrases’ (活句). Like that, today we want to honestly converse with each other about the problems each of us is currently facing.”

Then anyone could raise their hand and ask Sunim questions. During one hour, five people had conversations with Sunim. One of them talked about conflicts arising from still remaining only a child in their mother’s eyes despite being an adult.

“My Mother Still Treats Me Like a Child Even Though I’m an Adult, and It’s Hard”

“What specific issues are causing you difficulty?”

“How old are you?”

“I’m thirty-eight.”

“Are you married?”

“No.”

“If you get married and raise children, you’ll understand. This is difficult to understand just through explanation. Parents have this habit because they’ve raised their children for nearly 20 years. Don’t you develop a habit even after smoking just a few times? But when you take care of a child for nearly 20 years, it becomes a completely ingrained habit. So even though mothers think in their heads ‘My child has grown up,’ in their unconscious world, they always see their children as kids, whether they’re 30 or even 50 years old. It’s hard to quit smoking after just a few years, so it’s difficult to change a habit of several decades.

Whatever your mother says, just say ‘Thank you.’ Because this is a problem that cannot be fixed. However, if you’re over 20 and an adult, you can make your own decisions and act on them. If you continue to listen to your mother after becoming an adult, you’re not a free person but your mother’s slave. We can listen to others’ opinions, but we have the right to make the final decision ourselves. However, we cannot change your mother’s nagging and worrying heart.

So how can you get along with your mother without conflict? You need to acknowledge your mother’s feelings. So whatever your mother says, you should say ‘Yes, I understand. Thank you,’ and first accept that ‘From mother’s perspective, that’s possible.’ At the same time, since you’re a free person, you can act according to your own thoughts. If your mother says ‘Don’t go out today,’ you respond ‘I understand.’ This means you understand your mother’s feelings. If your situation allows you not to go out, don’t go; if you must go out for something important, just go. Your mother might get angry saying ‘Why did you go out when you said you wouldn’t?’ In that case, you can answer ‘I’m sorry. I wasn’t planning to go out, but something suddenly came up and I had to go.’ If you continue this way a few times, the relationship will naturally improve. At first, your mother will be angry that you don’t listen to her, but over time she’ll think ‘My son does what he needs to do’ and give up.

You need to have the perspective of both understanding your mother’s feelings and doing what you need to do. You’re not opposing your mother’s opinion; you’re doing what you need to do. However, you should say ‘I’m sorry’ to your mother. Because you didn’t accept your mother’s opinion, she might feel a bit disappointed from her perspective. It’s not good to block your mother’s freedom to speak by getting angry and saying ‘Stop nagging!’ or ‘Don’t interfere!’ That creates conflict. Whatever your mother says, you should say ‘Yes, I understand.’ Then later your mother will complain ‘You just say yes but don’t actually do it.’ When that happens, you can again say ‘I’m sorry.’ This is wisdom. You should always understand and accept the other person’s feelings. And at the same time, you need to go your own way. If you do this, there’s no problem living with your mother. Are you living with your mother now, or separately?”

“I live separately.”

“Then your mother can’t nag continuously, so there’s no big difficulty. Whatever your mother says, just say ‘I understand.’ When she tells you to come home, you should say ‘I understand.’ You shouldn’t say ‘I’ll come.’ Because saying you’ll come is a promise. If you don’t go, it’s breaking a promise. Saying ‘I understand’ means you understand your mother’s feelings. You can go if you’re able to, and not go if you can’t. If your mother says ‘Why didn’t you come when you said you would?’ you can explain, ‘I’m sorry. I was planning to go but something suddenly came up and I couldn’t.’ This is different in nature from lying.”

“Thank you.”

Questions continued to follow.

I’m worried about whether I can properly complete my major in Germany.

I find it difficult to say no. What kind of practice should I do?

My son got angry when I told him he needs to be careful while driving. How should I deal with my son who is inexperienced at driving?

How can I know if I’ve done my best in something?

After conversing with five people, when there were no more questions, the lecture ended earlier than scheduled.

After the lecture, there was a book signing session. Sunim warmly greeted the German attendees.

German students who had graduated from Jungto Dharma School also attended the lecture, took commemorative photos with Sunim, and pledged to continue their practice steadily.

After taking a commemorative photo with the International Division volunteers who prepared the German-interpreted lecture, Sunim took a brief rest in the waiting room.

As the sun set and evening arrived, Korean expatriates began arriving at the venue one by one. Volunteers warmly welcomed the audience.

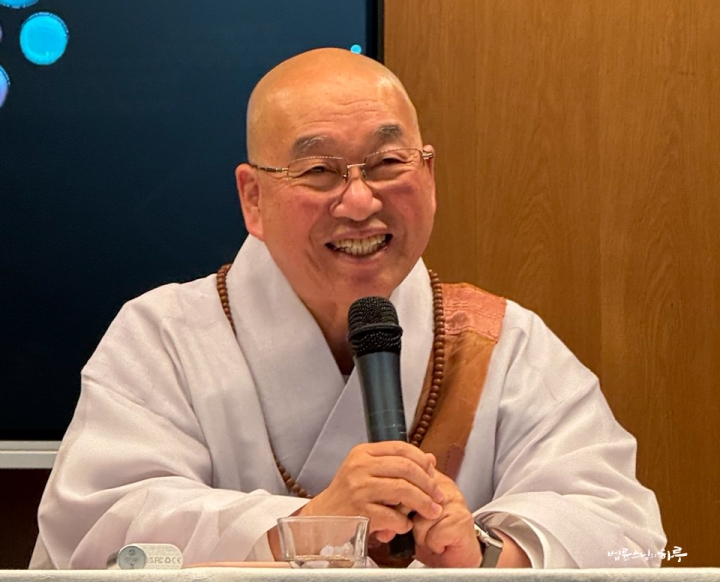

With about 90 people seated, the Dharma Q&A for Korean expatriates began at exactly 7 PM. When the introductory video about Sunim ended and he walked out from backstage, thunderous applause and cheers poured out.

Sunim smiled and gave his opening remarks.

“I’ve given lectures as long as three and a half hours, and as short as 15 minutes. One day, a university hospital requested a lecture. After I spoke for about 5 minutes at the beginning and said ‘Now let’s talk about what you’re interested in,’ no one said anything. So I said if there were no questioners by the time I asked three more times, I would leave. Then one person asked a question, we conversed for about 10 minutes, and since there were no more questioners, I immediately ended the lecture. The audience’s eyes went wide. Because I have nothing special to say to you. If I had something to say, the talk would be long, but I have nothing to say. If you want to talk about something, we just have a conversation about that topic. So since no one had any particular area of interest, I finished quickly.

Your Questions Are the Topic of the Lecture

Just now, I gave a Dharma Q&A with German interpretation. Since the audience was German, only about 30 people attended, and after five people asked questions and there were no more questioners, I ended the lecture in one hour. After finishing the lecture and going outside, someone said they couldn’t ask a question and tried to ask on the spot. However, I didn’t respond. I only have conversations during this given time and don’t continue private conversations separately. No matter how much someone cries and complains outside after it’s over, I ignore them and leave. (Laughter) So if you want to talk, it would be good to do so in this setting.”

Then anyone could raise their hand and ask Sunim questions. During two hours, six people had conversations with Sunim. One of them confessed that although they were reading Seon Buddhism books and continuing practice through meditation, in daily life they were still caught up in right and wrong and struggling with afflictions.

Can office workers also end the cycle of reincarnation and achieve enlightenment in this lifetime?

“Since you say you’re interested in Seon Buddhism, I’ll speak directly. First, the very thoughts of ‘Is this the right path?’ or ‘Is this the correct way?’ are themselves non-Seon Buddhist ways of thinking. Since Seon Buddhism exists in a perspective without right and wrong, in a perspective where all phenomena are empty, such thoughts are already not from a Seon Buddhist viewpoint. Second, thoughts like ‘Will I be dragged by karma and have to go through rebirth again in this life?’ or ‘Can I achieve enlightenment and attain Arhatship?’ already presuppose that rebirth exists. How do you know whether rebirth happens or not? Yet you’re already thinking with the belief that rebirth exists. It’s like a Christian asking, ‘Who does Buddhism think created this world?’ Buddhism doesn’t say that someone created this world. This question presupposes that the world was created, so it cannot be answered. Similarly, when Christians ask how to get to heaven, that’s a task within the Christian worldview and can only be valid within it. Likewise, when you ask how to avoid rebirth or how to attain Arhatship, you’re already presupposing Buddhist concepts or traditional Indian concepts. However, Seon is about negating these very concepts. So everything you’re saying can be said to be from a non-Seon Buddhist perspective.

You are within the world of belief and conceptual thinking. Seon intuition is about breaking through this world of belief and conceptual thinking. Although you’re studying Buddhism now, your Buddhism is no different from Christianity. Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Tibetan Buddhism – each has something they pursue within their own belief systems. But Seon is about shattering these very frameworks of belief and concepts. It negates the premise of ‘this can be done if you do it this way.’

The question ‘Who created this world?’ presupposes that this world was created. When someone asked me that question, I responded by asking, ‘How many hours does it take to cook rice with sand?’ The person then asked back, ‘How can you cook rice with sand?’ My question was asking how many hours it would take for it to become rice. This question presupposes that rice can be made from sand. But what about in reality? You cannot cook rice with sand in the first place. Therefore, the phrase ‘how many hours’ becomes completely meaningless. Similarly, the question ‘Who created this world?’ asks about ‘who,’ but it presupposes that the world was created. If the world was not created, then asking about ‘who’ has no meaning whatsoever.

Like that, Seon negates all concepts. It doesn’t accept any presuppositions. Because it stands from the perspective of ‘directly pointing to the mind, seeing one’s nature and becoming Buddha’ (直指人心 見性成佛), what you’re talking about might be asked from the standpoint of a Christian or Buddhist believer, but it’s not from the Seon perspective.”

“Thank you. Then from the Seon perspective, what direction should we take to practice and attain enlightenment?”

“In Seon, how to practice and how to attain enlightenment is not a major concern. Even the idea of enlightenment presupposes that there is something to be enlightened about. Let me tell you a story about a Seon master. A Seon master was sitting in meditation when his teacher suddenly came and asked what he was doing. While a passerby might ask out of curiosity, it doesn’t make sense for the teacher who told him to meditate to ask such a question, does it? The Seon master answered, ‘I’m meditating.’ The teacher asked again, ‘Really? What are you meditating for?’ The Seon master answered again, ‘I need to meditate to become enlightened.’ The teacher left as if he didn’t understand what that meant. The meditating Seon master was dumbfounded. His teacher was asking as if he were a stranger passing by, even though he clearly knew what and why he was doing it.

The Seon master then resumed his meditation. But this time, there was a ‘scraping’ sound right next to him. When we meditate, we shouldn’t pay attention to anything even if lightning strikes, but in reality, when there’s a strange sound nearby, we wonder what’s going on and open our eyes to look. The Seon master also couldn’t overcome his curiosity and slightly opened his eyes to look beside him, and saw his teacher continuously rubbing two bricks together. ‘Master, why are you rubbing the bricks?’ the Seon master asked. The teacher replied, ‘I’m making a mirror.’ The Seon master asked again, ‘Master, how can you make a mirror by rubbing bricks?’ Then the teacher looked straight at the Seon master and asked back, ‘How can you become enlightened by meditating?’

The teacher demonstrated through his actions that saying ‘I’ll become enlightened through meditation’ or ‘I’ll become a Buddha through meditation’ is as useless as trying to make a mirror by rubbing bricks. The Seon master was shocked and asked, ‘Then how can I become enlightened?’ But the teacher asked him another question: ‘If a cart doesn’t move, do you whip the horse or the cart?’ When a cart doesn’t move, you naturally whip the horse, right? The Seon master answered dismissively, ‘Of course, you whip the horse!’ Then the teacher shouted, ‘Then why are you whipping the cart?’ It’s said that at that very moment, the Seon master became enlightened.

Seon has no presuppositions about ‘becoming enlightened’ or ‘meditating.’ It doesn’t even accept such words. The extreme expression of this is ‘If you meet the patriarch, kill the patriarch; if you meet the Buddha, kill the Buddha.’ Since Buddha and patriarch are also concepts, we shouldn’t put forward such presuppositions. Not having any presuppositions is Seon. Only when you simply notice your mind right now without any presuppositions like in Vipassana practice, or simply doubt by asking ‘What is this?’ like in Ganhwaseon (看話禪) practice, can it be called Seon.”

“Then does Seon deny attaining arhatship or the Buddha’s enlightenment itself?”

“Those are all just thoughts. Contemplating a ‘hwadu’ means stopping thoughts. If you think about what the Buddha said, what enlightenment is, what the stages are, like you’re doing now, it’s already not Seon. Meditation is also just noticing, not thinking. What you’re doing now is contemplating various things. This is closer to Buddhist philosophy. Seon is stopping contemplation.

People who practice Seon don’t think about ‘What happens when I die?’ or ‘What happens when I become enlightened?’ The very talk of being enlightened or not enlightened proves that you’re already contemplating and discriminating. Buddhism, Christianity – these are all in our world of contemplation and discrimination. Since Seon is stopping contemplation, it’s just being here. From the perspective where discrimination is cut off, there are no problems. So you don’t need to try to do anything. You’re not doing something yourself; you’re thinking ‘I should do it.’ If someone is lying down thinking ‘I should get up, I should get up’ while making efforts, resolutions, and determinations, are they in a state of being up or lying down?”

“They’re lying down.”

“All our efforts are needed when we’re lying down. That’s not yet getting up. But what if you just jump up? Do you need effort to get up? No effort is needed. So Seon is not about making effort but just getting up. If thinking ‘I should get up’ is contemplation, resolution, and determination, then Seon is just getting up. It’s not ‘I should go!’ but just going. It’s not ‘I should give!’ but just giving. It’s not ‘I should do it!’ but just doing it. This is called ‘letting go’ (放下着). You just do it.

When you wake up in the morning and have something to do, just do it. There’s no need to be lazy, and no need to hurry. There’s nothing to strive for and nothing to be lazy about – this is the natural state. When a cow grazes, it does so slowly but steadily. When it’s done grazing, it sits quietly and ruminates. Is the cow trying to die from boredom then? No. It’s just being leisurely. Living according to these natural principles is freedom.

Life should just flow like water. When it pools, it stops; when there’s a slope, it flows; when there’s a cliff, it becomes a waterfall. Just do what needs to be done, whether busy or slow. If there’s nothing to do, you can just be leisurely, but you all writhe in boredom when there’s nothing to do. You make a fuss when busy saying it’s hard, make a fuss missing your parents when they’re not around, and make a fuss saying you don’t want to see them when they are. You make a fuss saying it’s annoying when living together, and make a fuss about being lonely when alone. You make a fuss when there’s too much work, make a fuss when there’s no work, make a fuss about how hard it is to go to work when employed, and make a fuss about not being able to find a job when unemployed. But nature isn’t like that. It’s good to have, and it’s good not to have. Yet it’s neither lazy nor impatient.

With a Seon perspective, you lose interest in things like ‘Do this, you’ll go to heaven; do that, you’ll go to hell’ or ‘Do this to become enlightened.’ Those are just people’s thoughts. The Bible says God said this and that, but did people write it or did God write it?”

“People wrote it.”

“But people who believe in Christianity think God said those words. Similarly, among the things written in Buddhist scriptures saying the Buddha said this or that, there are contents that someone recorded based on their own thoughts throughout history. So when reading scriptures, we need to examine from what era and perspective they were recorded. We shouldn’t think everything written in Buddhist scriptures is the Buddha’s words. Since they were all written by people, the perspectives differ depending on when they were written. For example, what would happen if Buddhist scriptures were written in a communist society? You couldn’t write content criticizing communism. In a monarchical era, you had to praise the king to survive as a religion of that time. You had to praise that one becomes a king by accumulating much merit in past lives; you couldn’t say that kings and commoners are the same. Thus, Buddhism that has passed through monarchical eras, caste societies, and gender-discriminatory societies has many parts that have become distant from the Buddha’s original teachings. The idea that you become a man by accumulating much merit in past lives and become a woman by committing many sins reflects the concepts of a gender-discriminatory society. The idea that you become nobility by accumulating merit and become a commoner by committing sins was all created to rationalize the caste society. However, the Buddha’s original teachings negated all of these things.

People make various claims in every era. That’s why the Buddha said, ‘Truth cannot be verified based on ethics or morals, customs or habits, precepts or scriptures transmitted from the past.’ Yet many later Buddhist scholars tried to verify truth based on the Buddha’s words. That’s why Seon negated written words with the principle of ‘not establishing words’ (不立文字). However, today’s Seon is again interpreting the recorded sayings of patriarchs. This deviates from Seon.

We must return to the original spirit of Seon. The moment we acknowledge any presupposed concept, we can say it’s not Seon. The idea that you must hold the hwadu ‘What is this?’ to practice meditation is also a concept. This is called a dead phrase (死句), or dead language. In the Buddha’s time, just as you and I are conversing now, people with anguish resolved their troubles through dialogue with the Buddha, thinking ‘It’s nothing special.’ The scriptures are collections of those dialogues. Buddhist scholars have continued to study and analyze those dialogue records. From a Seon perspective, these are dead phrases. To become living phrases (活句), we need to talk about our problems here and now. Don’t talk about others’ stories; talk about your own story – what state you’re in now, what your problems are. Only by approaching it this way can it become a living phrase.

But even you are not asking what your problem is right now, but just asking things like ‘Can I become an arhat?’ or ‘Can I become enlightened?’ – having doubts about phrases someone wrote in the past and conversing about them. Seon practice is not being attached to such things.”

“Thank you. I understand well.”

Questions continued to follow.

I keep getting angry at my child, and I’m worried it might damage their self-esteem. How can I control my anger?

I’ve been living with my narrow-minded husband for 10 years. Even after fighting with him, I don’t understand why he got angry at all.

The stress and hurt I receive from my family is so great that I’ve cut ties with both sets of parents. What perspective should I have?

I’m curious about what Sunim thinks about artificial intelligence.

I’m conflicted when my new studies overlap with the Weekly Dharma Assembly time. Is flexible practice possible?

After answering all the questions, Sunim finally gave words of encouragement for the Korean expatriates.

“When you all came from Korea to Germany, did you think it was good fortune from your wise choice? Or did you come as refugees with no choice? Which was it?”

“We thought it was good fortune from our wise choice.”

“If you who have such good fortune complain about having too much work here or things being difficult and hard, you’re not seeing yourselves properly. Each of you may be experiencing various difficulties, but they’re all just minor problems within your good fortune. You say married life is difficult, but you all received congratulations when you got married, didn’t you? Then is marriage good fortune or misfortune? It’s good fortune. You just have some problems within that good fortune right now.

Catching Good Fortune and Then Letting It Go Is Not Misfortune

If there really is a problem, you can just give up that good fortune. At worst, you’re back to square one. Divorce is just breaking even, not misfortune. It’s just catching good fortune from zero base and then letting it go, not misfortune. Similarly, if living in Germany is hard, you can return to Korea. You can let go of the good fortune you caught. So there’s really no need to worry. ‘I’ll do what I can, and if it doesn’t work out, I’ll go back to Korea.’ ‘I’ll do what I can, and if it doesn’t work out, I’ll get divorced.’ You can think like this. Getting a job is also good fortune. Do what you can, and if it doesn’t work out, quit. You’re just letting go of the good fortune you caught – what’s the problem? So there’s no need to worry.

But the problem is that human greed is endless. We keep wanting good fortune on top of good fortune. Good fortune is something you can catch and let go, or maintain. Try following the good fortune you’ve caught, and if it doesn’t work out, let it go. Catching good fortune and then letting it go is not misfortune. Being born into this world is also good fortune. Dying is letting go of good fortune, not misfortune. There are beings who weren’t even born, so what do people who have the good fortune of being born have to complain about? (laughter)

If you have that perspective, there are no problems. You all belong to the group of people who have caught good fortune, and you can think of yourselves as just having minor problems within that. So there’s nothing to worry about. Since you’ve come to Germany, try doing what you can, and if it doesn’t work out, have the perspective that you’ll return to Korea. Returning to Korea is giving up good fortune, not failure.”

The lecture concluded with loud applause.

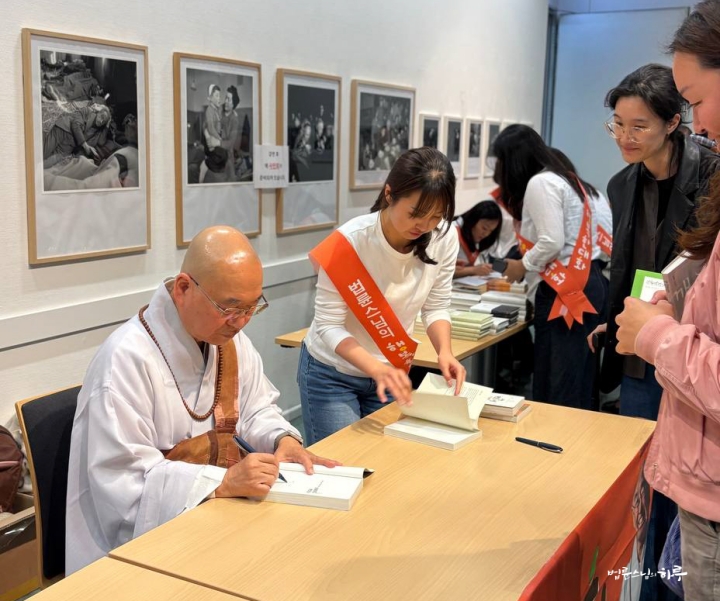

A book signing session began immediately. Most of the attendees lined up to receive Sunim’s autograph. Sunim made eye contact and greeted each person individually.

“Thanks to you, Sunim, I’m living happily. Thank you.”

Many people expressed their gratitude, saying that their lives had become happier after listening to Sunim’s Dharma talks.

After all the attendees had left the venue, Sunim took a commemorative photo with the volunteers who had helped prepare the lecture.

After expressing his gratitude to the volunteers, Sunim moved to his accommodation. The volunteers had a mindful sharing session with Dharma Teacher Myodeok. They exchanged heartfelt words, encouraging each other for their hard work. The person who provided German interpretation during the German-language lecture shared their thoughts first.

“Thanks to your concern and support, I was able to complete my interpretation duty. Rather than feeling I had to interpret, I wanted to do it, and I enjoyed it because you trusted me with this task. I could feel that Sunim pays careful attention even to the interpreter during his lectures.”

“I was active in the College Student Association 15 years ago but took a break. This lecture has motivated me to enroll in Jungto Dharma School and restart my activities with Jungto Society.”

“When I first participated as a volunteer at a lecture, I was confused and disoriented, but today, thanks to our continued coordination, we worked together like family. I feel proud and happy that the lecture concluded successfully.”

The volunteers calmly shared their thoughts and reflected on their time together.

Sunim arrived at his accommodation at 10 PM and concluded his day.

Tomorrow, Sunim will travel by train from Düsseldorf to Berlin. In the afternoon, he will conduct a live Friday Dharma Q&A broadcast, and in the evening, he will continue with the fifth Dharma Q&A lecture of the European tour in Berlin.