June 27, 2025. INEB Day 2, Discussion on Education, Happy Dialogue (1) Seoul

Hello. Today is the second day of the INEB (International Network of Engaged Buddhists) Study Tour. Sunim spent the entire day discussing the topic of ‘education’ with INEB participant monks, and in the evening, he gave a Happy Dialogue Dharma Q&A lecture.

After completing morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Peace Foundation. He started the day at 8 AM with a meeting with a North Korea expert. After discussing how to navigate US-North Korea relations following the US airstrikes on Iran, the meeting concluded.

At 9 o’clock, Sunim went to the auditorium on the 9th floor to participate in the INEB Study Tour. The topic for discussion throughout the day was ‘education.’ First, there was time to introduce Jungto Society’s educational programs. Kim Mi-sun, a volunteer who conducts the English Jungto Dharma School, explained the educational goals and programs of Jungto Dharma School, Sutra Course, and Happiness School.

“Jungto Society’s Buddhist propagation begins with the Jungto Dharma School course. Participants who complete the course are encouraged to become Jungto Society members. They also move on to the next course, the Jungto Sutra Course. Those who complete the Jungto Sutra Course are encouraged to become leading members. I myself have walked a similar path. We also operate the ‘Happiness School’ for general citizens, which doesn’t use religious language…”

Next, Ven. Khongsin, who serves as the principal of Wat Nicrotharam Temple Buddhist School in Thailand, introduced the school’s operations and educational goals.

“Wat Nicrotharam Temple Buddhist School was established in 1993 to address the shortage of resident monks and novices at the temple. It provides secondary education, and students learn not only the knowledge and skills necessary for Buddhist rituals but also Thai language, mathematics, English, and ethics education.”

It was impressive that the educational curriculum realizes holistic education by collaborating with the local community and including nature conservation and vocational skills training.

Next, Ven. Sayadej from Laos presented about Ongtue Sangha College.

“Since its establishment in 1929, Ongtue Sangha College has grown into Laos’s leading higher Buddhist educational institution. Currently, it operates a 4-year degree program centered on Buddhist studies and English education, with meditation practice and internships included as mandatory courses. Graduates work as teachers in Buddhist high schools nationwide and in Buddhist-related institutions…”

It was impressive that they pursue integrated and modern Buddhist education through connections with local communities and academic exchanges with international Buddhist universities.

After the presentations, there was a Q&A session. Various questions poured in as participants showed deep interest in each other’s activities.

INEB participant monks asked many questions about the specific methods and educational content of Jungto Dharma School and Happiness School. Sunim added detailed explanations.

“I listened well to your presentations. The three cases presented today each focused on different target groups in Buddhist education. Jungto Society introduced educational programs for the general public, Thailand introduced regular educational courses for young novices. This can be seen as a regular curriculum equivalent to middle and high school. And Laos introduced regular Buddhist university education courses for ordained monks. It was good to see how Buddhist education is being conducted for various educational audiences.

Jungto Dharma School: Practice-Centered Buddhist Education to Overcome Suffering

As explained earlier, let me provide some additional explanation about Jungto Dharma School operated by Jungto Society. The educational target of Jungto Dharma School is general adults who are beginning their journey in Buddhism. Education is conducted online, with classes once a week for six months. Anyone aged 19 or older can participate. Classes are usually conducted with 7 students forming one group, and each group is assigned 1 facilitator and 1 co-facilitator. When 7 such groups come together, they form one class, and each class is assigned 1 Dharma Teacher and 1 administrator. Students can freely ask questions to the Dharma Teacher whenever they have questions. Two 50-minute video lectures are provided online each week, and students watch them individually. Then, once a week, they gather online to share their thoughts and reflections on the teachings, taking turns to speak. If they don’t understand the Dharma talk content well or have questions, they can ask the assigned Dharma Teacher at any time and receive personal answers.

Additionally, weekly practice assignments are given based on the topics covered in the Dharma talks. For example, becoming aware of anger might be given as a practice assignment. During the week, students observe instances when they got angry, when they felt anger but held it back, and compare these experiences to how they were before studying Buddhism, checking for any changes in themselves. In the next class, they share what they felt while doing the assignment. Some people find the practice goes well, while others struggle with it. Through this process, they share experiences with each other and continue learning. In other words, students watch the Buddhist lectures individually, and when they gather together, the time is mainly spent sharing reflections. This can be seen as a process of making Buddhist teachings their own. Rather than understanding Buddhism philosophically or doctrinally, the goal is to apply it to their own lives and come even a little closer to nirvana, a state free from suffering. About once every month and a half, all students gather together for a Dharma Q&A session with me. The curriculum covers two main topics: ‘The Buddha’s Fundamental Teachings’ and ‘The Life of the Buddha.’

Happiness School: A 4-Week Mind Study Program Anyone Can Start Without Burden

However, Happiness School has a slightly different character from Jungto Dharma School. Even though we try to explain things as simply as possible using everyday language at Jungto Dharma School, students still need to learn basic Buddhist terms and concepts. They need to learn terms like ‘Four Noble Truths,’ ‘Middle Way,’ and ‘Dependent Origination.’ No matter how much Jungto Dharma School claims to teach beyond religious boundaries, it can still feel burdensome to those of different religions or those who have resistance to religion. So we created Happiness School to allow many citizens to study the mind without any resistance. At Happiness School, we only approach questions like ‘Why does the mind suffer?’ and ‘How can we escape from this suffering?’ We don’t use Buddhist terms like the Four Noble Truths. This makes it easy for anyone to participate, and the course is short—just one month. If they like it after trying it, they can do it again later.”

After finishing the morning program, at 11:30 AM everyone went down to the basement dining hall together for lunch. The volunteers had prepared food with care and a welcoming heart.

After each person served themselves as much food as they wanted to eat, everyone together offered a Theravada-style prayer of gratitude.

Venerable Kongsin from Thailand expressed admiration upon seeing the neatly prepared food.:

“If we eat like this every day, we’ll become healthy.”

Sunim replied with a smile:

“We don’t usually eat like this either. We prepared this special food because the venerable monks are visiting.” (Laughter)

After finishing the meal, Sunim went to the kitchen to thank the volunteers.

“Thank you for the meal.”

The program resumed at 1:30 PM. Before starting the dialogue, Kim Yoon-mi, a JTS volunteer who recently visited the Myanmar earthquake relief site, explained the damage situation and JTS’s relief activities. While watching videos of the relief efforts, participants deeply empathized with the suffering of Myanmar’s disaster victims and once again felt the urgent need for solidarity and support to alleviate their pain.

A Q&A session followed. The INEB participant monks were very intrigued by the phenomenon of ordinary citizens asking Venerable Pomnyun Sunim about their life concerns and finding relief from their suffering after hearing his answers.

How Can We Approach Lay Practitioners Who Cannot Open Their Hearts to Monks?

Sunim answered.

“While we can say that such tendencies are somewhat stronger in the Theravada tradition, Korea is actually not much different. However, Dharma Q&A is the result of trust built over a long time. It’s because people have developed the belief that they can talk to Venerable Pomnyun Sunim about anything. Moreover, Dharma Q&A isn’t just about talking to a monk individually; it’s about revealing one’s inner self in a public space. This is actually very difficult. It’s not easy to share personal stories like experiencing sexual assault or going through a divorce in front of many people. But they share because problems can’t be solved without speaking up. In fact, it’s difficult to share such stories anywhere in the world. I rarely do personal consultations. Only in very exceptional cases, like with politicians or celebrities whose situations could cause social repercussions, do I offer individual counseling. Most questions occur in public Dharma Q&A sessions.

While most people find it difficult to talk about their concerns, what they experience is actually happening everywhere in the world. So the very act of sharing already means they’re halfway prepared for healing. Even in Korea, people don’t often come to monks to discuss their personal suffering. But if we look at the Buddha’s life, he always listened to people’s suffering and spoke with them. People who were suffering from the death of a son, or those struggling with illness or family deaths, came to the Buddha. Just because we say people can talk about anything doesn’t mean they will. Trust must be built first. These days, people don’t even readily share their stories with their parents.”

Venerable Kongsin from Thailand shared his concerns about how to teach happiness to people. Sunim first defined what happiness is and then explained from what perspective he conducts Dharma Q&A sessions with people.

What Kind of Education Is Needed for People to Be Truly Happy?

“When we say we’re healthy, what state can we call healthy? Do we need to be strong to be healthy? Do we need to be able to run fast to be considered healthy? That’s not the case. Being healthy means not being sick. Children can be healthy as children, elderly people can be healthy as elderly people, and people with disabilities can be healthy even with their disabilities as long as they’re not sick. Being unable to see doesn’t necessarily mean being sick. Just as we define physical health as ‘not being sick,’ according to the Buddha’s teachings, happiness can be defined as ‘the absence of suffering.’ Nirvana is a state without suffering. Happiness is not about pleasure but about the absence of suffering.

What the world calls happiness refers to pleasure. However, where there is pleasure, there is inevitably suffering. Suffering and pleasure repeat endlessly, and this is called samsara. In traditional Indian culture, samsara refers to the cycle of birth and death, but in the Buddha’s teachings, samsara refers to the repetition of pleasure and suffering. Breaking free from samsara means stopping the repetition of suffering and pleasure. Therefore, ‘a state without suffering’ simultaneously becomes ‘a state without pleasure.’ In other words, it’s a state of tranquil stillness. We call this ‘nirvana.’ Since most people think of pleasure as happiness, we must first help them adopt the perspective that ‘a state without suffering is happiness’ and then guide them on that path.

In our reality, suffering constantly arises. So we need to think about why we suffer. It’s important to examine our current state. If we’re suffering, we need to look at why we’re suffering and identify the cause of suffering. Only then can we realize that there’s actually nothing to suffer about. Then the suffering disappears. By approaching it this way, we come to realize that anyone can live without suffering. We shouldn’t view nirvana as too abstract but understand it as a state that anyone can attain.

However, in reality, many people remain in a state of suffering. The first reason is ‘attachment.’ The more fundamental cause is ‘ignorance.’ When we break through this fundamental ignorance and see things as they are, suffering disappears. That’s why awareness is most important. First, we must realize that we’re in a state of suffering. We must become aware that we’re currently in a state of ignorance. When correct awareness continues in this state of ignorance, suffering disappears. That’s why we must always check our own state first. We need to know that suffering doesn’t come from outside but from our own ignorance.

With this approach, people don’t need to know Buddhist terminology. For example, if someone says they’re suffering because they failed an exam, I ask why failing an exam causes suffering. They might respond, ‘Then should I be happy about failing the exam?’ I ask again.

‘Did you fail the exam just now, or was it already decided a few days ago?’

He answers that the result was determined a few days ago. If you’re suffering because you failed the exam, shouldn’t you have been suffering from that moment? But weren’t you smiling and going about your life until you saw the results? In the end, the only change that occurred at that moment was that you learned something you didn’t know before. You simply found out at that moment that you had failed the exam, so why are you suffering? When we approach it this way, we come to realize that there’s actually no reason to suffer.

Let’s say you go to the hospital today and are diagnosed with cancer. Most people would suffer. But the cancer didn’t develop today. It was already in your body yesterday. Yet you weren’t suffering yesterday, but you are today. Why? You simply learned today what you didn’t know before. It’s actually fortunate that you found out you have cancer. Yet the reason you feel suffering is not because of the cancer itself, but because of your mind that cannot accept it. When we approach it this way, anyone can realize that there’s actually nothing to suffer about. This realization is the path to happiness. Happiness doesn’t mean ‘being joyful’ but rather ‘a state without suffering.’ Just as anyone can live healthily, anyone can live without suffering.

Sometimes we get hurt and feel pain. But when we treat it, it heals. Similarly, while we may sometimes suffer, when we realize the facts again, we can reach a state without suffering. The reason we learn fundamental teachings like the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path in Jungto Dharma School is to accurately understand these facts.

When we say we know something, it means we know it through seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and thinking. For me, this world exists through ‘knowing.’ Knowing is nothing special; it’s simply the function of the twelve sense bases (十二處). We must approach the Buddha’s teachings experientially in our actual lives like this. Of course, it’s generally not easy to realize these facts in a short time. That’s why we need to practice consistently in our daily lives. Some people change quickly, others are slower, and sometimes people quit in the middle. When people attend Jungto Dharma School and their minds become a bit more at ease, they recommend it to others around them, and that’s how it gradually spreads. However, Jungto Dharma School has not yet spread universally throughout Korean society.”

After two hours of conversation, they took a short break.

Before resuming the dialogue, they watched a video of Jungto Society’s 6.13 Grand Dharma Assembly held last year and introduced the purpose of the event. Then Sunim took more questions.

Everyone showed great interest in the Happiness School, so Sunim explained the curriculum in more detail. They then had a full discussion on the topic of “new member education.” Various questions followed: “Is there Buddhism in North Korea?”, “Can people from Thailand visit North Korea?”, “How does Sunim make contact with North Korean people?” There was also interest in inter-Korean relations and the religious situation in North Korea.

Participants continued with questions about the content that Venerable Kongsin had presented in the morning.

They spent time resolving questions about Thailand’s education system, such as “Can students who graduate from Buddhist schools enter regular universities?” and “Why do they attend monastic schools instead of regular schools? Is it for economic reasons or because of interest in Buddhist practice?”

Questions about Korean Buddhism also arose.

“Besides Jungto Society, how many other Buddhist educational institutions are there in Korea? Are there any run by the government?”

“In Thai Buddhist schools, even monks don’t choose Buddhism. They study law, sociology, political science, and science, then leave the temple to find employment. How is it in Korea?”

Everyone expressed concern about the declining number of Buddhist followers. Sunim shared his thoughts on this issue as they concluded today’s discussion.

“The decline in Buddhist followers and ordained monks is not unique to Korea. In 10 or 20 years, your countries will likely experience similar situations. Of course, it may not be as severe as in Korea, but I believe the overall direction will be similar. That is why you, too, need to start thinking about how to respond to these changes.

Can Buddhism, Which Young Generations Are Leaving Behind, Become Hope Again?

I believe that hope for overcoming the crisis of modern civilization lies in the Buddha’s teachings. In the past, people were materially deprived, so religious practices of praying for blessings were prevalent. Now that the problem of making a living has been resolved, doesn’t mental suffering still remain? This suffering requires spiritual healing, and I think the Buddha’s teachings are most effective for this. While meditation can help, meditation alone seems insufficient. We need to learn the Buddha’s teachings and attain wisdom. I believe we need to return to the Buddha’s fundamental teachings and understand the principles of how the mind works. This education should be applicable to daily life and easy to understand. We need efforts to study the Buddha’s teachings beyond traditional religious views and apply them to eliminating people’s suffering.

The Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism has been conducting a movement to expand meditation nationwide starting this year. This is because they recognized limitations in spreading Buddhism religiously. In a few days, I’ll visit the Jogye Order and hear explanations directly from officials, but the Jogye Order is researching ways to communicate culturally with young people. Since authoritative and conceptual approaches from the past no longer work with younger generations, they are considering more approachable cultural methods.”

Finally, after watching a video together about JTS rebuilding a school for over 4,000 students in Syria, which had been destroyed by earthquakes and war, the conversation came to an end.

As guests arrived, Sunim immediately moved to the reception room, while the INEB participant monks moved to the basement dining hall for light refreshments.

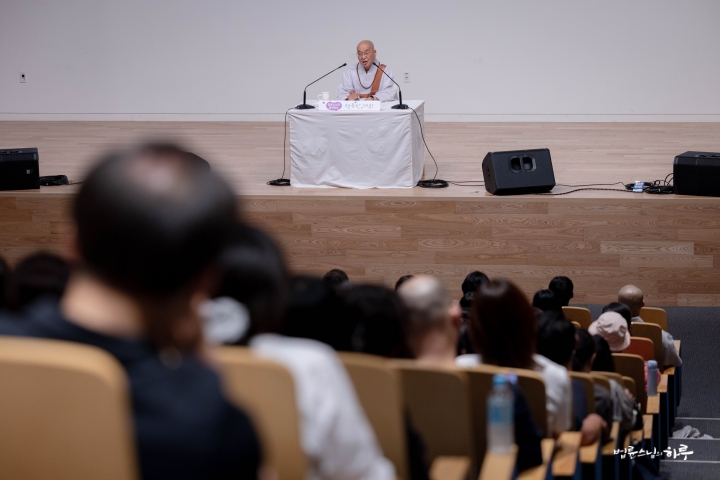

As the sun set, at 7:10 PM, everyone gathered at the second-floor lounge and moved together to the basement auditorium where the Happy Conversation Dharma Q&A was to be held.

When Sunim and the INEB participant monks entered the auditorium, everyone welcomed them with enthusiastic applause. Today’s lecture began with an exciting song performance by the indie band “Magic Donkey.”

Next, Lee Seon-ho from the Cheongju branch of Jungto Society performed a parody of the song “Age, Go Away” titled “Defilements, Go Away,” filling the lecture hall with laughter and energy.

After the introductory video about Sunim ended, he came up on stage to great applause. About 3,900 people were connected to the YouTube live stream. Sunim greeted everyone with a smile.

“Today, several monks from Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia have come to observe Korean Buddhism and Jungto Society. Please give them a warm round of applause.”

Shall We Begin This Conversation Where Suffering Disappears?

“Dharma Q&A is not a place to convey certain knowledge or beliefs. It’s not about sharing prepared stories either. It’s a time to comfortably reveal the anguish in our hearts and talk about it together. Through conversation, you might think, ‘It’s not such a big deal!’ When thinking alone, it might feel unbearably painful and seem like a huge problem, but when we talk together, you realize, ‘It wasn’t worth being so distressed about!’ and the suffering disappears. This kind of conversation is called Dharma discourse. Dharma discourse isn’t about explaining Buddhist doctrine; rather, it’s when suffering disappears during our conversation about suffering. In English, we call it a Dharma Talk.”

“This time today is for sharing Dharma discourse with you. We’ll have conversations using the troubles and suffering each of you experiences in life as topics. At first glance, it might look like personal counseling, but actually, we’re engaging in Dharma discourse. The material for the Dharma discourse is the specific difficulties you face in life, and we have conversations based on those difficulties.”

Sunim immediately began taking questions and started the dialogue. Over the course of an hour and a half, seven people asked Sunim questions. One of them sought Sunim’s advice on how to solve the problem of feeling lonely because there was no one around to confide in.

How Can I Overcome Loneliness When I Can’t Share My True Feelings?

“If you want to have deep conversations, why don’t you just have them? You say you can’t speak, but is it really that you can’t speak, or is it that you don’t want to?”

“I think I don’t want to.”

“If you don’t want to speak, then don’t.”

“Then should I live a lonely life?”

“That’s your choice. You’re choosing not to speak because you don’t want to, so you can’t say someone else is making you lonely. If you don’t want to speak, just don’t. But then why do you say you’re lonely?”

“Looking back now, I think I didn’t want to speak.”

“If you didn’t speak because you didn’t want to, then just accept that as cause and effect. If I don’t share anything with others, why would they open up to me about every little thing? So if I want to talk, I should talk. If I don’t want to, I shouldn’t. That’s my freedom. Similarly, others have the same freedom. So saying you’re lonely doesn’t really mean much. Why do you feel lonely? When do you feel lonely?”

“I just feel like I don’t have anyone I can share my true feelings with.”

“You just said you don’t want to open up. It’s not that you don’t have anyone to talk to—you don’t want to open up, so why do you say you don’t have anyone to talk to?”

“Yes, you’re right.”

“You said you don’t want to open up, right? Is it that you don’t have anyone to open up to, or is it that you don’t want to?”

“I don’t think I have anyone I want to open up to yet.”

“Are you looking for someone you want to open up to?”

“I think so.”

“You’ll never find such a person, even if you search until you die. Right now, you’re looking for someone who will never criticize you and accept everything you say. But expecting someone to accept everything you say isn’t realistic. Whatever reaction they have is their freedom, and if you want to open up, you should just do it. It’s not that you can’t—you don’t want to. Yet you think ‘I can’t open up because there’s no one,’ which means you’re blaming others for your own problem. From my perspective, your viewpoint seems misguided.”

“Yes. My perspective seems wrong.”

“How is it wrong?”

“I didn’t realize that I didn’t want to speak all this time.”

“You thought you wanted to open up but couldn’t, right? But actually, you didn’t speak because you didn’t want to. It’s not that you couldn’t. When the alarm goes off in the morning and you’re lying in bed thinking ‘I should get up, I should get up’—is it that you want to get up but can’t, or is it that you don’t want to get up?”

“I don’t want to get up.”

“But we think ‘My body won’t listen to me, so I can’t get up.’ Actually, it’s not the body that’s the problem—I don’t want to get up. Who is responsible? I am. If you don’t want to get up, then don’t. Then you’ll be late. Just accept being late as the consequence. If you don’t want the consequence, you have to get up even if you don’t want to. So how do you get up? Just get up quickly. How? Just spring up.

Let’s say you’re holding a hot coal in your hand. Your hand would be hot, right? You’d say ‘Ouch, it’s hot!’ but you don’t let go and ask ‘How do I let go of this?’ Are you asking because you don’t know how to let go? Or are you not letting go because you don’t want to?

In reality, what do you do when you’re holding something hot? You say ‘Ouch, it’s hot!’ and drop it. How do you let go? You just let go. If you know it’s hot, you just let go. There’s no other method. But you all keep asking ‘How do I let go of this?’ Does that question mean ‘I don’t want to let go’ or ‘I want to let go’?”

“It means I don’t want to let go.”

“That’s right. When you’re still lying down, you need determination and resolve to ‘get up!’ Once you’re up, you don’t need determination or resolve. It’s the same with practice. Practice doesn’t require determination or resolve. Having determination and resolve means you’re still lying down. You all always just make determinations and resolutions, but nothing actually gets resolved. That’s because you don’t see through to the essence. If you see through to the essence—that it’s a feeling of ‘not wanting to’—then if you want to sleep, just sleep. You’ll face other losses, but at least you slept, right? Or just get up. Then you won’t sleep, but you won’t be late either.

For example, let’s say there’s poison in some food. If someone says, ‘I want to eat this food,’ the Buddha’s teaching is very simple: ‘That food contains poison.’ That’s it. Stating that it contains poison is simply explaining a fact, not a command saying ‘eat it’ or ‘don’t eat it.’ The Buddha always spoke only facts. He didn’t tell fanciful stories; he spoke only the truth. Once I become aware of that fact, the next step is my choice. If I want to eat it, I can eat it and die. When we follow our desires, consequences follow. When we borrow money, the consequence is having to pay it back with interest. Once we know this, we can decide, ‘Fine, I’ll pay it back.’ I get diarrhea when I eat ice cream, so I usually don’t eat it. But what do I do when people keep offering it to me? I eat it. And then I get diarrhea. But I don’t say, ‘I shouldn’t have eaten it.’ Because I already anticipated the diarrhea when I ate it, I simply think, ‘I’m receiving the consequences.’

I travel all around the world. The probability of dying in a plane crash or car accident is probably high. So would I have regrets if an accident happened? No, I wouldn’t. It’s the life I chose, and it would simply be the consequence of that choice. You all engage in activities that increase such probabilities, yet you don’t accept the results. You have regrets and say, ‘I shouldn’t have done it.’ That’s an attitude of not taking responsibility for your own choices.

When we don’t know the truth, we have regrets and suffer. But when we know the truth, we make our own choices. If you’re okay with having a stomachache after eating, then eat. If you don’t want to be in pain, don’t eat. But people say, ‘I want to eat it, so how can I not?’ The Buddha said, ‘Still, don’t eat it,’ but I say, ‘Go ahead, eat it and die.’ Since you chose that path, receive its consequences.

The questioner isn’t unable to open up – they simply don’t want to. This isn’t about the other person; it’s about you. It’s because you can’t trust others, and ultimately, you’re the one who becomes lonely. If you don’t want to talk, you can live alone. There’s no obligation to speak. It’s fine to live in silence for your entire life. However, if you feel it would be good to open up, then speak at that time.

Practice isn’t necessarily about doing something. Not doing something and accepting the consequences is also practice. What’s important is the attitude of willingly accepting those consequences. Sometimes things happen that strain your body. Then you can choose not to do it, or decide to do it and accept the pain. When I have overlapping commitments, I just do them even though I know I’ll be in pain. When I hurt afterward, I think, ‘I knew this would happen’ and accept it. I don’t suffer because of the pain, and I don’t regret it. I simply accept that my body hurts.

You need to make a choice now. Will you open your heart even if you don’t want to and live without loneliness, or will you hold on tight and live in loneliness? Which will you choose?”

“I’ll practice opening up.”

“Good. When you attend Jungto Dharma School, there’s time to practice ‘opening your heart.’ We call it ‘mindful sharing.’ Opening your heart requires practice too. At first, the words get stuck in your throat, seeming to come out but not quite, but if you keep at it, it becomes nothing special. When you’re struggling alone, it feels huge, but when you actually speak it out, it’s often really nothing at all. After you open your heart, you realize it was actually nothing.”

Questions continued to come in.

My parents oppose my marriage because of fortune-telling. I’m trying to get married without their help, but my father says he won’t leave my boyfriend and his parents alone, which scares me. What should I do?

I’ve been working at a large corporation for 25 years, but I think I’ll be asked to resign soon. I could hold on, but I’m thinking about starting a second life. Is it okay to take on a new challenge at fifty?

After bouncing between part-time jobs, I’m now running a YouTube channel. However, YouTube income is unstable compared to the time invested, and I’m getting exhausted from being so conscious of subscribers’ reactions. What mindset should I have?

Outsiders have come to our neighborhood for a Moa Town project and are getting residents’ consent. I need to rally residents to oppose the project, but it’s giving me headaches and making my chest feel tight.

After taking three more questions from the floor, the lecture ended after 9 PM.

A book signing session was immediately held below the stage. Many people brought Sunim’s new book “Buddha the Revolutionary” to get it signed.

“Thanks to you, Sunim, many of my worries have been resolved. Thank you.”

Everyone expressed their gratitude to Sunim. Sunim made eye contact and exchanged greetings with each person.

Finally, after taking a commemorative photo with the volunteers from the Seoul-Jeju Branch of the Special Happiness Movement Headquarters who prepared today’s lecture, Sunim left the venue.

The INEB participant monks moved to the 10th floor conference room for a mindful sharing session. Venerable Kittisara from Myanmar shared his thoughts.

“Venerable Pomnyun’s answers during the Dharma Q&A were different from what I expected. If someone asked about their parents opposing their marriage, I would have told them to listen to their parents. But while that answer might be moral, it would have actually caused more suffering for the questioner. However, Venerable Pomnyun’s answer was that there’s no right or wrong in any decision. When he said that whatever decision you make, you must accept the consequences, I saw the questioner’s anguish disappear. I could see how Buddha’s teachings are applied in real life.”

The staff members were all moved seeing how the INEB participant monks immediately understood and were touched by Venerable Pomnyun’s message. Today was a time to discuss extensively how Buddhism resolves people’s suffering and then see and hear specific examples firsthand.

Tomorrow is the third day of the INEB study tour. In the morning, they will visit Bongamsa Temple in Mungyeong to observe how the meditation hall operated by the Jogye Order functions, and in the afternoon, they will have an intensive discussion on the theme of ‘practice’ at Mungyeong Jungto Retreat Center.