Mar 27, 2025 – 100-Day Dharma Talk Day 39, Sutra Lecture 6, Buddhist Social Studies Course Lecture 6

Hello. Today is the 39th day of Venerable Pomnyun Sunim’s 100-Day Dharma Talk. Today features both a sutra lecture and a Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture.

After completing his morning practice and meditation, Sunim headed to the Jungto Social and Cultural Center to deliver the sutra lecture.

About 120 people were seated in the third-floor Dharma hall, while approximately 560 people connected via the online livestream. After the audience requested the Dharma teaching with three full bows, Sunim ascended to the Dharma seat.

Today is the sixth session of the Diamond Sutra lecture series. Sunim began by summarizing the content covered in the previous session. He then continued with explanations of Chapters 9 and 10 of the Diamond Sutra.

“Subhuti had another question. Until now, he had understood that through diligent practice, one first attains the fruit of Stream-Entry (Sotapanna), and as practice deepens, one attains the fruit of Once-Returner (Sakadagami), then Non-Returner (Anagami), and finally Arhatship. But when the Buddha said earlier, ‘There is no Dharma to be attained,’ Subhuti wondered, ‘How then are the four stages of enlightenment achieved?’ Knowing Subhuti’s thoughts, the Buddha began Chapter 9 of the Diamond Sutra with another question.

If There Is No Dharma to Be Attained, How Are the Four Stages of Practice Achieved?

What are the four stages of enlightenment? When one who doesn’t understand the truth first awakens to it, the mind becomes clear. This is like a light being turned on in a dark room, or like finding the path after being lost in the mountains. However, knowing the path doesn’t guarantee reaching the destination. One might lose the way again during the journey, or face numerous obstacles ahead. In Theravada Buddhism, this initial discovery of the path is called Stream-Entry (Sotapanna). In Zen (Seon), it’s called the initial glimpse of one’s true nature (Chogeonseong), and in Mahayana Buddhism, it’s called the Path of Seeing (Gyeondo).

If you have begun practicing, you should at least achieve Sotapanna in this lifetime. Sotapanna means “entering the stream that leads to becoming a noble one.” In Chinese characters, it is also called “Yeryu (預流)” or “Ipryu (入流),” meaning that one has stepped into the stream of becoming a noble one. Even when a practitioner becomes a Sotapanna, “momentary ignorance” still remains. “Momentary ignorance” refers to unconscious ignorance that activates when encountering certain situations. For instance, if someone suddenly hits you, you might instantly become angry. This happens because while ignorance has disappeared from your conscious mind, it still remains in your unconscious. What is needed at this point is repentance (懺悔), recognizing “I have lost my mindfulness.” You must repeatedly return to awareness after losing it. During meditation, we repeatedly notice our breath, lose awareness, and then return to it again. Through such numerous practices, the duration of our mindfulness extends. Similarly, through repentance, as we repeatedly become aware of our unconscious ignorance, we gradually maintain mindfulness even when facing challenging situations. Initially, we might lose mindfulness all ten times out of ten, but as we continue practicing, the moments of maintained awareness increase. For example, if there are ten moments of encountering challenging situations, maintaining mindfulness in seven of those moments is what is called the fruit of Sotapanna (須陀洹果) among the four fruits of Sravaka.

The second stage is Sakadagami. Sakadagami is the state where one maintains mindfulness in at least eight out of ten situations. Is it easier to maintain mindfulness seven times out of ten? Or is it easier to go from seven times to eight times? Going from seven to eight is much more difficult than going from one to seven. Sakadagami is written in Chinese characters as “once-returning” (一往來). This term comes from the Indian worldview, meaning that one will be reborn in the human realm only once more before never returning again. In other words, one has only two rebirths remaining: once in the human realm and once in the heavenly realm. After that, one attains enlightenment and is liberated from the cycle of rebirth in both human and heavenly realms. Using a basketball analogy, it’s like making eight out of ten shots. You might miss occasionally, but rarely. Even if someone suddenly provokes you to anger, you remain mindful in most cases, losing awareness only about two times out of ten. That’s why it’s said that two rebirths remain. So why is it called “once-returning” rather than “twice-returning”? Because the final rebirth is in the heavenly realm, from the perspective of the human realm, only one return remains, hence “once-returning.”

The third stage is Anagami. In Chinese characters, Anagami is written as “non-returning” (不還), meaning one never returns to the human realm again. An Anagami will be reborn once in the heavenly realm before attaining liberation. In terms of practice, this is the stage where one maintains mindfulness nine out of ten times, missing only once.

The fourth and final stage is Arahant. An Arahant no longer experiences rebirth in any realm. Using the basketball analogy, it’s like never missing a shot when throwing the ball ten times. From now on, every shot goes in. In terms of practice, because one never loses mindfulness in any situation, there is no suffering whatsoever.

The Arhat who never falls back, the Anagami who falls back once but never again afterward, the Sakridagami who may fall back once more but not after that, and the Sotapanna who may fall back several times but never returns to being an ordinary being – these are the four stages of enlightenment for the Sravakas. Subhuti understood that through practice, one could attain these four stages in sequence, but when the Buddha said, “There is nothing to attain and nothing to expound,” he wondered what it meant when people said, “I have attained the stage of Sotapanna,” “I have attained the stage of Sakridagami,” “I have attained the stage of Anagami,” or “I have attained Arhatship.”

At that time, Hinayana practitioners divided the path of practice into four stages and became attached to distinctions like “I have attained the stage of Sotapanna” or “I have attained the stage of Sakridagami.” This is critically examined in the ninth section of the Diamond Sutra, “Single Mark, No Mark.” The Dharma actually has no stages, yet practitioners created these distinctions and became trapped in them. For example, when the light in this room is turned off, it’s dark; when it’s turned on, it’s bright. It’s meaningless to distinguish whether we’ve lit a candle, a 5-watt bulb, or a 10-watt bulb. We simply say, “The light is off” or “The light is on.” Therefore, if a monk claims, “I have completely awakened to everything,” that person has not truly awakened.

The section “One Characteristic is No Characteristic” means that although we divide the path into four stages out of practical necessity in reality, there is only one path. The true meaning of “one characteristic” is actually “no characteristic.” This is because whenever we conceptualize something, its opposite concept inevitably emerges. For example, when we conceptualize something as “medicine,” the relative concept of “poison” arises. When we define something as a “part,” the relative concept of “whole” emerges. Thus, when we establish one thing, another necessarily appears. Therefore, to achieve true oneness, we must not establish anything at all. Only in the state of “no characteristic,” where nothing is established, can true oneness exist. Even in the scientific world, where matter always has antimatter and positive always has negative, the true meaning of “one” is “no characteristic” – where there is nothing to be called “one.” This is the meaning of “One Characteristic is No Characteristic.”

The Pure Land Is Here and Now as Bodhisattvas Work Toward Completion

The next section of the Diamond Sutra is the tenth section, “Adorning the Pure Land.” Let’s read it together. “One should give rise to a mind that dwells nowhere.” Typically, we think that to generate a thought, we need a goal or object, such as “I should do this!” or “Let’s try that!” We believe that without any thought, the mind doesn’t arise. We think there must be “something to cling to” for the mind to emerge. “One should give rise to a mind that dwells nowhere” means “generate thoughts without attachment.” It means to encounter the six sense objects—seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and thinking—without clinging to them while still generating thoughts. Adorning the Pure Land doesn’t simply mean planting flowers in a garden or creating social systems; it means that when discrimination disappears from my mind, that place itself becomes the Pure Land. Therefore, for a bodhisattva, the Pure Land is not a realm that is already completed somewhere else. The Pure Land exists right now, in this moment, as the bodhisattva works toward completion. This is the core message of the Diamond Sutra and forms the foundation of all Mahayana scriptures. This is why the Diamond Sutra can be considered the scripture that most essentially contains the fundamental ideas of Mahayana Buddhism, based on the wisdom of prajna.

Sunim concluded the lecture, stating that he would continue explaining the 11th section of the Diamond Sutra in the next session.

After the lecture, participants gathered in groups to share their thoughts while Sunim went to the basement cafeteria to have lunch and converse with Bhikkhuni Soya, who had come from Russia.

Bhikkhuni Soya became connected with Jungto Society and Venerable Pomnyun Sunim through her acquaintance with Rinchen Dawa. She operates a meditation center in Mongolia and sought Sunim’s advice on how to spread authentic Buddhism in Mongolia. They engaged in an extensive conversation on this topic.

After finishing his meal, Sunim visited the volunteers who had been preparing lunch every day to encourage them and took a commemorative photo together.

“You’re all working so hard. Let’s take a photo together.”

After taking the commemorative photo, Sunim moved to the reception room to continue his conversation with Bhikkhuni Soya. They shared tea for an hour and took photos together.

“Thank you so much for giving me your valuable time despite your busy schedule.”

Bhikkhuni Soya expressed her gratitude and departed.

In the afternoon, Sunim attended to administrative matters in his office and prepared for the evening Buddhist Social Studies Course lecture.

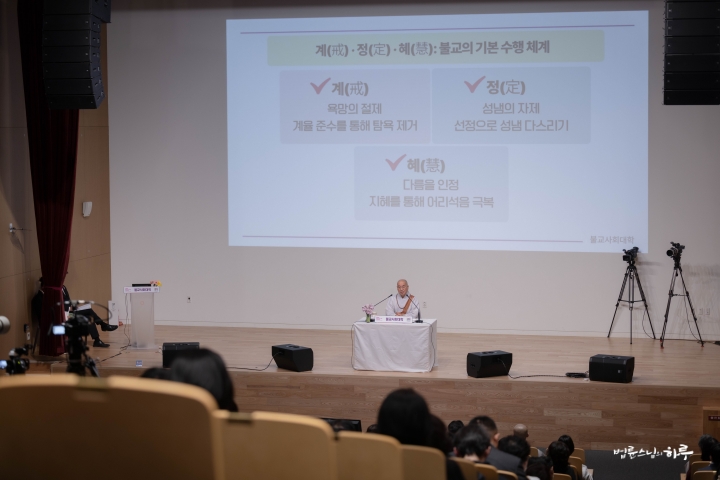

As the sun set, at 7:30 PM, Sunim delivered the sixth lecture of the Buddhist Social Studies Course in the basement auditorium of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center. Through the previous five lectures, participants had studied Buddhist worldview, practice theory, cosmology, and perspective on life. Today’s sixth session focused on “Buddhist View of Life,” exploring the understanding of a life free from suffering.

About 200 students of the Buddhist Social Studies Course were present in the basement auditorium, while approximately 1,900 people connected to the online live broadcast. Before beginning the lecture, students were asked questions and their responses were collected. After watching a video summarizing these results together, Sunim began his lecture.

Sunim posed a question about whether human destiny is predetermined, then proceeded to discuss the Buddhist view of life.

“Today, I would like to discuss the Buddhist view of life from a practice-oriented perspective. It’s about examining how I, born as a human in this world, am living. I want to explore whether my destiny is predetermined or not.

Are the Four Pillars of Destiny or Fate Truly Predetermined?

People in ancient times believed that fate was predetermined. If we consider the idea that our destiny is fixed as truth, we can disprove it by finding just one exception. The Buddha pointed out the contradictions in the belief of predetermined fate using very specific examples.

For example, suppose someone killed another person with a knife. When people say, ‘You are a bad person!’ the killer claims, ‘I am not guilty.’ How could they argue they’re not guilty? First, they might claim that God commanded it. They might say, ‘God told me to kill this person!’ suggesting they had no freedom in the matter since God controls everything, so it’s not their fault. Second, they might argue that according to their Four Pillars of Destiny, they were meant to kill that person. The logic is that since it was predetermined from birth that they would kill that person at that time, it’s not their fault. They simply followed their destined path. Third, they might claim that in a previous life, that person killed them, so in this life, they were destined to kill that person. They argue that since the murder was predetermined from a previous life, they couldn’t change it.

If we view everything as predetermined by fate, humans cannot be held accountable for their actions. Whether determined by God, one’s Four Pillars of Destiny, or past lives, everything would already be destined. This cannot be understood through reasonable logic. That’s why the Buddha gave specific examples.

“If fatalism were true, wouldn’t it be impossible to hold people accountable for killing or harming others?”

With these words, the Buddha rejected fatalism as incorrect. In ancient India, people believed that gods determined whether a person would be reborn in heaven after death. The Brahmin priests would perform rituals saying, “O Brahma, please grant rebirth in heaven!” People thought that these ceremonies guaranteed heavenly rebirth, while even those who lived virtuously couldn’t reach heaven without such rituals. However, one young man noticed contradictions in this belief. Yet he couldn’t reject these teachings outright because so many people had followed them for so long. So he asked the Buddha:

“Is it true that one can be reborn in heaven if Brahmin priests come and pray for them?”

The Buddha very kindly enlightened a young man. He took the young man to a pond and tossed a stone into it. The stone sank to the bottom. The Buddha asked the young man.

“What happened to the stone?”

“It sank to the bottom.”

“Why did it sink?”

“Because the stone is heavy, it sinks to the bottom. That’s the law of nature.”

The Buddha asked again.

“Then if Brahmin priests came here and prayed to the gods to make the stone float on the water, would it float?”

“No, it wouldn’t.”

“Why wouldn’t it float?”

“It’s natural for heavy things to sink. That’s the law of nature.”

Then the Buddha said:

“That’s right. Just as you say. If a person lives by telling lies, stealing from others, getting drunk and causing trouble, using abusive language, committing sexual assault, and even killing others, the karma they create is dark and heavy, and like that stone, it naturally sinks down, taking them to hell!”

The young man had a great realization and said:

“I understand, Buddha! I understand, Buddha! I truly understand, Buddha!”

He responded with such repeated praise because he clearly understood the principle after hearing the Buddha’s words. The young man’s doubts completely disappeared. He realized that one doesn’t go to heaven through prayer, nor through divine power. The Buddha’s teaching is that if heaven or hell exists, one goes there according to the karma one has created. So who determines whether you go to heaven or hell? Not God, but yourself. It depends on how you live your life. No one else controls your destiny.

Can Everything Happen According to My Will?

After hearing this, you might mistakenly think, “Does this mean everything happens according to my will?” That’s not what I mean. We cannot say that our lives are completely limited, nor can we say that we can do whatever we want without any limitations. For example, humans are made of matter. Life phenomena exist on the foundation of matter, and mental phenomena exist on the foundation of life. No matter how exceptional our mental phenomena or how highly developed our life is, we cannot escape the physical limitations. However, we can partially transcend physical limitations. For instance, we can slightly defy gravity. A rabbit can jump from the floor onto a desk, defying gravity. A stone cannot move from the floor to the desk. Similarly, while not everything in our destiny is predetermined, it’s true that certain broad boundaries are set. For example, it’s not predetermined whether we’ll go this way or that way every second, whether we’ll think this thought or that thought, or whether we’ll eat or not eat. However, we can say it’s predetermined that all humans will die within 200 years.

Sometimes Adapt, Sometimes Pioneer: The Middle Path

Therefore, when living our lives, we need to both adapt to our environment and pioneer new paths. If we are told to simply adapt unconditionally, human autonomy cannot be expressed at all. If we are told to pioneer everything, severe side effects occur, such as environmental destruction and war breaking out everywhere. When we overemphasize divinity, we suppress the human mind; when we overemphasize free will, all kinds of side effects like environmental destruction and war emerge.

We must accept the given conditions while using our free will to improve our environment. This is because humans possess both qualities—the ability to adapt to the environment and the ability to pioneer. Buddhism teaches us to maintain a middle path perspective between these two qualities. We should not lean to one extreme, claiming “it’s this” or “it’s that.” Of course, for the unwise, destiny plays a greater role than free will in navigating this world. However, for the awakened, we can say that free will plays a more significant role.

Then why do humans experience suffering? The reason is that we fail to see facts as they are. Why does this phenomenon occur?

When discussing the size of this cup, it’s small compared to the microphone, but large compared to the cup lid. The cup itself is neither big nor small. This is where our perceptual error occurs. We think small things are small and big things are big, but this is an illusion. We perceive things as “big” or “small” only in comparison to other things; in themselves, objects are neither big nor small. Similarly, there’s no inherent “new” or “old” quality to things. These are merely issues of our perception.

We think colors themselves are yellow or red. But in fact, it’s just that something appears yellow to my eyes or appears red to my eyes. Would it appear yellow to a dog? What color would a color-blind person see? Everyone sees differently. Therefore, we cannot say that color itself is definitively one way or another. It simply appears red to my eyes or blue to my eyes.

This truth is the most difficult to realize. Most people either make the relative absolute or objectify the subjective. Therefore, we fail to see facts as they truly are. This misunderstanding is delusion (顚倒夢想) and ignorance. Sometimes when we practice, we become confused, wondering, “Is it this? Is it that?” At such times, most people say, “I don’t know.” But just recognizing that I don’t know is actually quite remarkable.

Why Do Perceptual Errors Occur?

Perceptual errors occur in us for several reasons. First, they arise from the limitations of human eyes that cannot see both the macro and micro worlds. Second, they occur when we absolutize what is relative. Third, they happen when we mistake subjective perceptions for objective reality. For example, if you look at a white wall through a red-colored lens, the wall appears red. It looks red to your eyes, but in reality, the wall is white. This way of viewing the world through one’s own lens is called “karma consciousness” (業識). When perceiving objects, the spectrum of habits and experiences accumulated throughout life becomes the color of your lens. This lens influencing perception is karma consciousness. Since people grow up with different experiences, some may see the same object as large while others see it as small. Similarly, some may think a Dharma talk is excellent while others think it’s poor. This happens because karma consciousness is at work.

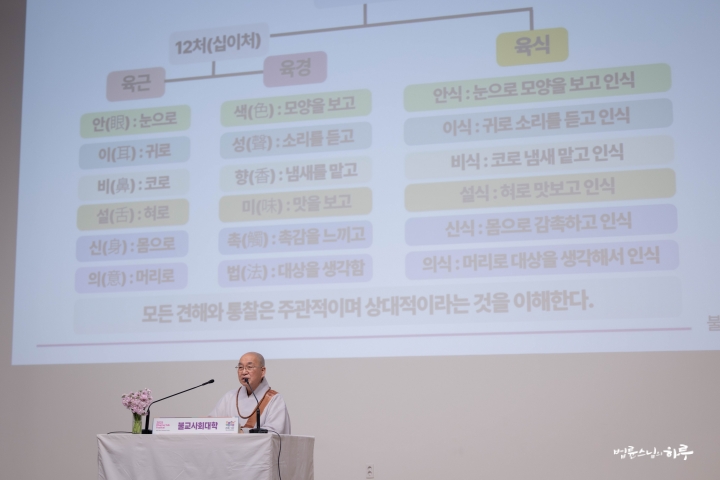

When we perceive objects, our six sensory organs—eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind—meet with the six objects of perception—form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental objects—creating the function of “knowing.” This is the “twelve sense fields.” Additionally, the six types of consciousness based on our life experiences combine with these twelve sense fields to create the perceptual process. The twelve sense fields plus the six types of consciousness form the “eighteen elements.” Since human perception encompasses the entirety of our world, Buddhism states that everything is contained within the twelve sense fields and the eighteen elements. The most important factor here is consciousness (識), as it forms the foundation of perception. Because of this foundation of consciousness, we feel differently when seeing the same thing, hear differently when listening to the same sound, experience different moods in the same situation, develop different desires in the same circumstances, and think different thoughts. Without even realizing it, consciousness has an enormous influence on our lives.

If we were to say that we are born with karma consciousness or that we are destined to live based on it, that would be a fatalistic view. Instead, the Buddha taught that karma consciousness is merely something that has been formed.

Let me give you an example. When walking a dog on a leash, sometimes the dog walks ahead of me, sometimes beside me, and sometimes lags behind. Did the dog take a walk according to its own will? For brief moments, it might have gone wherever it wanted, but in reality, it went where the owner led it. Similarly, you all think you live as you wish, but ultimately, you live according to your karma. That’s why people sometimes have the illusion that fate exists separately. If someone were to investigate how a person’s karma is formed and how it operates, and analyze that information with artificial intelligence (AI), it would become big data about that person. With such big data, one could freely manipulate that person.

How to Change My Own Destiny

But what if you realize that you’re being manipulated? You can break free from it. If someone offers you food with an appealing smell or taste, you would simply accept and eat it. However, if they tell you it contains rat poison, you would stop immediately. Although you were destined to die by acting according to your karma, you can stop abruptly when you become aware. Therefore, to change your destiny, you must be aware. You need to be conscious at the moment of reaction. When you’re awake, you stop living by habit. Thus, preventing habitual living is the highest goal of practice. From the perspective of worldly ethics and morality, we’re told to correct bad habits and cultivate good ones. But practice is somewhat different. Whether good or bad, all habits are actions where you are not in control. Even good habits occur without your awareness. They simply don’t cause harm. But you’re still being led by good habits just the same. Liberation means becoming free from the karma that has become habitual.

The fastest way to reach the goal of liberation is “awareness.” In other words, “being awake.” If a man is wealthy, handsome, and talented, the probability of me dating him is low because his standards would be very high. But if by chance I married him, suffering would follow. Why? A wealthy person commands the price of wealth. A handsome person commands the price of looks. If someone is handsome, seems good-natured, and is wealthy, many women would pursue him regardless of his marital status. So I would always live in distress over my husband’s issues with women. Yet I couldn’t leave him because I’d think I couldn’t find someone as good elsewhere. In secular terms, this is called “being stuck between a rock and a hard place.” So I live in suffering for my entire life. But is this predetermined fate? Or is it due to compatibility? No. It all happens due to ignorance.

The Reason Suffering Arises

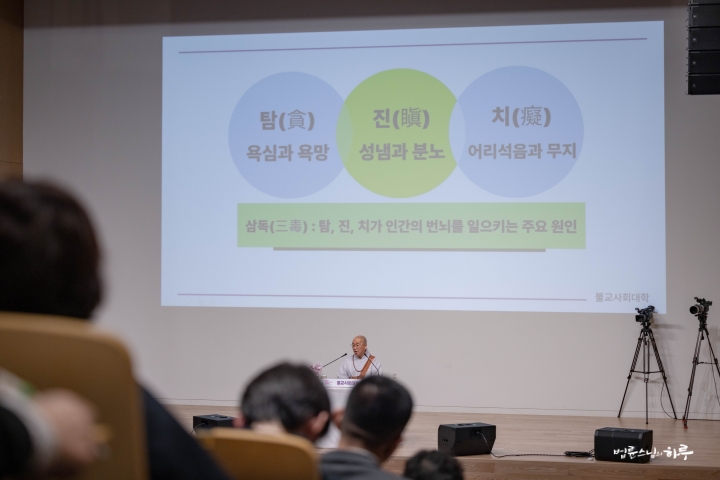

Then what causes ignorance? First, greed. We become blinded by desire. Second, temperament. We can’t control our own nature. Third, ignorance. We don’t understand the principle of cause and effect. These are called “desire(貪), anger(瞋), ignorance(癡).” In a word, it’s “ignorance.” That’s why the first step in the Twelve Links of Dependent Origination is ignorance. Breaking through ignorance and escaping foolishness is called “awakening.” Just as we wake from a dream, we awaken from ignorance, which is why we say “awaken” rather than “believe.”

So what is the method for removing the three poisons of desire, anger, and ignorance? The way to remove greed is to observe the precepts. The way to remove anger is to practice meditation. The way to remove ignorance is to cultivate wisdom. By practicing the threefold training of precepts, meditation, and wisdom, we can cross the ocean of suffering and live a life of freedom.

As we go through life, all kinds of things can happen. We need to appropriately accept these events while sometimes making improvements within reasonable boundaries. However, for events that have already occurred, an attitude of unconditional acceptance is necessary. Even when someone dies, if it has already happened, we must adopt the perspective that it is for the best. This is because we cannot turn back time. This doesn’t mean we should blindly submit to everything. Practice means doing our best to create certain changes while not being attached to the results. This is the Buddhist view of life.”

Today’s session focused on learning about the Buddhist perspective on life and how to live as the master of one’s own life. The sixth lecture concluded with the announcement that the next session would cover “Life’s Compass for Navigating the World,” exploring Buddhist values.

Participants gathered in groups for a sharing session. During this time, they had the opportunity to reflect once more on what they had learned today.

Tomorrow will be the 40th day of the 100-Day Dharma Talk. In the morning, Sunim will conduct the Friday Dharma Q&A for the daytime session in the main hall of the Jungto Social and Cultural Center basement, followed by the evening session of Friday Dharma Q&A.